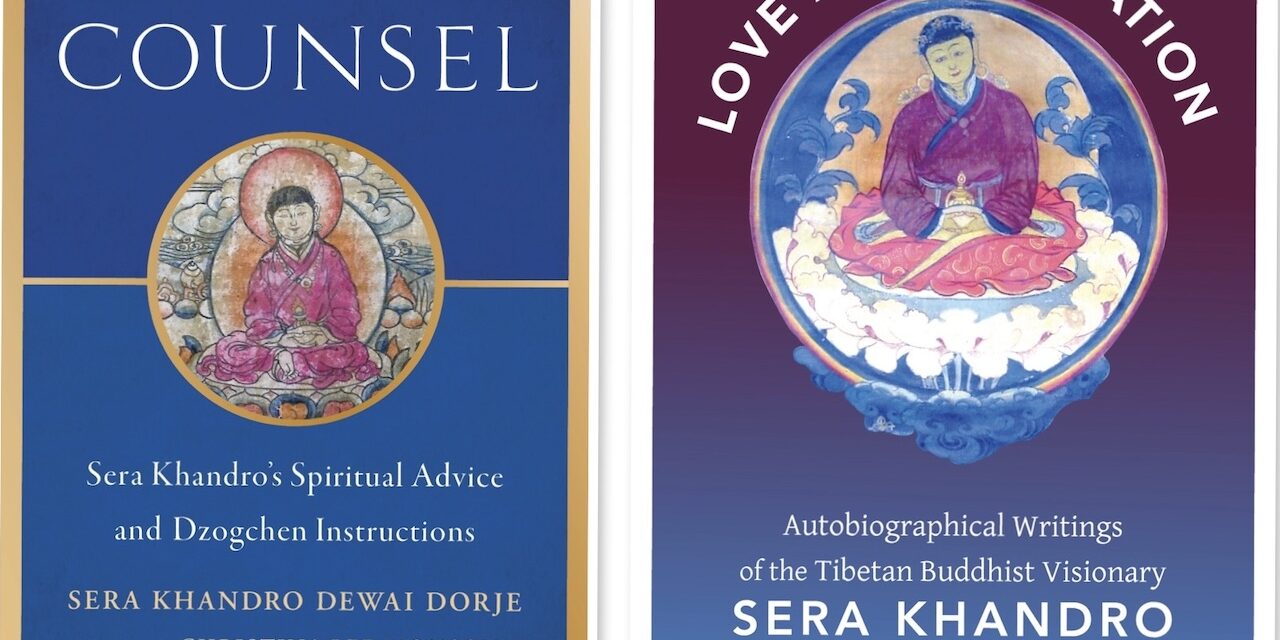

A Dakini’s Counsel, Sera Khandro’s Spiritual Advice and Dzogchen Instruction

translated by Christina Lee Monson, Snow Lion 2024, pp. 390, ISBN 9781611808841

Love and Liberation, Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro

by Sarah H. Jacoby, Columbia University Press 2014, pp. 422, ISBN 9780231147699

Review by Alexander Studholme

When Sera Khandro first heard the word “Dzogchen” as a little girl, tears flooded her eyes and the hair on her body stood on end, an early sign of her destiny as a dakini and terton. Other childhood auguries included bearing the physical marks of a dakini (such as white hairs growing from the crown of her head), pulling a phurba part way out of a rock and curing victims of smallpox by the power of mantra. A latter day Yeshe Tsogyal, A Dakini’s Counsel, translated by Christina Monson,is the first collection of her teachings to be published in the west.

Born to a wealthy family in Lhasa in 1892, Sera Khandro’s identification with Guru Padmasambhava’s famous consort was explicitly made in her lifetime both by herself and others. Her visionary communication with this queen of the dakinis was a constant theme of her inner life. As an infant she caught hold of a sunbeam and told her mother she was being taken to the realm of Yeshe Tsogyal’s lotus light, an event that left her unconscious for a week. Her autobiography repeatedly echoes the story of her illustrious predecessor. As teenagers, for example, both women escaped the prospect of an arranged marriage to leave home and follow their calling as the dakini partner of a powerful lama.

In Sera Khandro’s case, this took her to the badlands of the Eastern Tibetan province of Golok, where things could be very tough indeed for a young woman, far from home, conforming to neither of the two conventional female roles of wife or nun. She describes going cold and hungry, being kicked out of the monastery hall as a beggar and even having dog shit put on her head as she performed ritual prostrations. An old woman tells her: “Hey! Beautiful girl, you may be able to get free from the mouths of dogs, but with that figure it will be difficult for you to free yourself from being underneath men.”

The lama she was pursuing was called Drimé Özer, twelve years her senior and the son of the renowned terton Dudjom Lingpa (1835 – 1903), who was himself reincarnated as the incomparable Dudjom Rinpoche (1904 – 1987). But despite a powerful mutual attraction, Sera Khandro was prevented from living with Drimé Özer by the woman who was already his consort. Instead, she had to settle for an antagonistic relationship with another man, who traded her as a yab yum consort amongst other high-ranking lamas – to cure sickness and prolong longevity – and ended up suing her for custody of her son, though he was not actually the boy’s real father.

Sera Khandro did eventually enjoy three years together with Drimé Özer, a period of much happiness and spiritual creativity. They called each other “jewel of my heart” (snying gi norbu) and catalysed each other’s amazing treasure revealing activity. But when her lama died from the plague aged only 43 – preceded just three days earlier by the death of her five-year-old son – she was immediately expelled from his household and once again faced an uncertain future. Fortunately, someone recognized her outstanding qualities and took her under his wing: a compassionate tulku from Sera Monastery in Eastern Tibet. She spent the remaining sixteen years of her life at Sera – the name by which she is now universally known – and blossomed there to become a terton, writer and teacher of widespread repute up until her death in 1940.

To get an idea of how unusual Sera Khandro was, it is worth recalling that in Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Tayé’s One Hundred Treasure Revealers, compiled in the 19th century, only two of the tertons are women. Sera Khandro herself states that she was the only female terton in Eastern Tibet at that time. The size of her literary output – which includes her autobiography, four volumes of her revelations and a biography of Drimé Özer – makes her the most prolific female writer in the history of pre-1950s Tibet. Her Tibetan editors pronounce her to be a second Machig Labdron.

The fact that this remarkable yogini is now becoming known in the west is due to that Methuselah of modern Tibetan lamas Chatral Rinpoche (1913 – 2015), who first met her in 1927. Their connection was significant – his daughter Saraswati Devi is now recognized as Sera Khandro’s reincarnation – and he clearly regarded her as a very important teacher. In the early 1990s, he gave transmission of her written works to two North American women, whose own lives subsequently have been immersed in the opus of Sera Khandro.

Christina Monson lived in retreat under the direction of Chatral Rinpoche for many years, studying and practicing Sera Khandro’s teachings. Her book is an anthology of shaldam (zhal gdams), instructions given directly from guru to disciple, from dakini visions to advice on how to take illness onto the path. “These sacred teachings,” Monson writes, “… inspire and sustain me as my spiritual lifeblood.” They include communication with birds – as Sera Khandro puts it: “Dakini prophecies, delivered through the talk of feathered friends.” Monson might herself have been a teacher – Lama Tsultrim Allione invited her to Tara Mandala – but sadly she died in 2023 at the age of 54, when she remained in tugdam (thugs dam) for three days.

Monson’s book follows the publication, over ten years ago, of Sarah Jacoby’s Love and Liberation, a survey of Sera Khandro’s life and a tour de force of Tibetan Buddhist studies. Jacoby describes Sera Khandro’s many encounters with the dakinis and earth deities who controlled access to her termas, teases out the practicalities of being a yab yum consort and examines the permutations of Tibetan male-female relations to conclude that she and Drimé Özer really were truly in love. Jacoby brilliantly analyses the intricacies of the Tibetan religious world and the many ways Sera Khandro struggled to overcome the trials of having an “inferior female body” (skye lus dman pa).

Self-deprecation was one of her strategies to deflect chauvinistic antipathy. “… I have low intelligence and don’t even understand the meaning of ah,” she once avers. In a moment of pathos, she abandons the retrieval of terma on a mountainside for the most banal domestic reasons: to hurry home to avoid being scolded by her peevish man and to look after a crying baby. Jacoby is a deeply sympathetic and insightful guide. Her translation of Sera Khandro’s autobiography, currently in progress, is definitely something to look forward to.

Alexander Studholme is an independent scholar and author of The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum (SUNY Press 2002). He first heard the name of Namkhai Norbu on a trip to Tibet in 1993 and joined the Dzogchen Community in 1998. He lives in the city of Bristol, UK, a short drive away from Kunselling.

You can also read this article in:

Italian