At the end of my fourth undergraduate year of Medicine, 1977, I heard a rumor that Tibetan could be studied at the university in Italy, a claim I immediately dismissed as an unrealistic tall tale. But it was true! At the time, I was immersed in science: I religiously read Scientific American, and certain Indo-Buddhist ‘vibes’ were just little more than a curiosity to me. Nevertheless, the following academic year, to my family’s horror, I decided to go and study Tibetan in Naples. After several scattered readings, from Castaneda to Rampa’s fables and Taoism, Vajrayāna Buddhism struck me in fact as the only reliable tradition due to its rare continuity of transmission. For years, moreover, I was intensely praying in my heart to find someone who could show me a genuinely viable path to inner knowledge.

On my ‘first day of school’, I found only six or seven students in the classroom, and one peculiar guy, about whom one thing was crystal clear: he must have been Tibetan. This young professor was lean and so fit that I remember immediately comparing him to Bruce Lee. He spoke with a sweet yet very lively and distinct cadence, weaving an Italian in a way that would become familiar and dear to me over the decades. His teaching style was also decidedly, and delightfully, unconventional. One of the things he said in those first days was: “Tibetan…? Easy!” Alas…

At the end of each class, I would get up and leave, puzzling over why the others lingered instead of moving on, while being too introverted and shy to ask. But then, something strange happened in the following weeks: every night I had very vivid dreams in which this Tibetan told me many profound and fantastic things, which in the dream I understood, but in an unexpressed and undefined way. It happened night after night, in a way I had never experienced before, and that has never recurred to this day. Each morning I woke up stunned, unfortunately remembering absolutely nothing specific of that avalanche of communications, and in class I spent the entire time staring in bewilderment at this odd professor, obsessively wondering who he truly was. I could barely hear his explanations on Tibetan language…

In the hallways, I began hearing whispers that ‘Norbu’ was a ‘Master’. What…? A ‘Master’‽ My thoughts and emotions became tumultuous. Then one day, someone from the group mentioned they met with ‘Norbu’ in some sort of gym. So in the afternoon I went to this underground basement, accessible by a few steps. When I saw a dozen pairs of shoes outside the door, all my anti-cult and charlatan alarms went off. Had it not been for the insistence of a friend, I would have turned back immediately. But I entered, sat cross-legged in the front row, and the ‘professor’ began to speak. It’s hard to convey what happened next without resorting to traditional phrasing: the ‘wheel of Dharma’ began spinning powerfully, not as a fantasy, but as a very real, precise, sharp, and majestic experience.

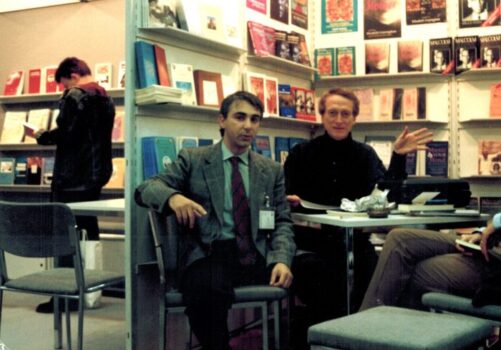

First days at Merigar with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu on the right, center Roberto Curtis and Giovanni Arca on the left.

That was the beginning, and then came the many years in Naples, the countless informal yet special moments with the Master, the formalization of the Dzogchen Community, the purchase of Merigar, my long involvement with Shang Shung Publications, experiences in Gakyils, the Merigar Letter, The Mirror itself, and so on, all the way to these lines I am writing in the Gar of a sun-drenched Tenerife. But my very first ‘encounters’ with the Master happened simply in his class and in my inexplicable dreams.

Of course, I have many memories of moments and events with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. Sometimes, I have shared the less private ones with fellow practitioners, as anecdotes where memory becomes edifying and inspiring. Writing memories, however, is somewhat different: oral communication is flexible, relying also on tone, body language, context, and is tailored, so to speak, around the listener; the written word is instead unchangeable and fixed for everyone, and the interpretations are often unpredictable. Anecdotes are also often self-referential or even self-congratulatory. I therefore hesitated, but considering the spirit and purpose of this column, here are some moments that I can share, hopefully in a lighthearted and perhaps even slightly amusing way. And I will do so precisely as a brief list of small anecdotal stories.

Star Trek and Kung Fu

When I discovered the Master liked my favourite TV shows, Star Trek and Kung Fu (aired in Italy since the early ’80s), I was thrilled! Watching them with him was priceless. He would occasionally comment, engrossed: “You see, you see… This being [an alien] could really be like that,” or, “Of course, this is possible in that dimension…” Kung Fu was intriguing too, as it centered mainly on psychophysical meditative techniques. Flashbacks showed the protagonist, David Carradine, recalling his old Taoist master dispensing pearls of wisdom. The Master often added enthusiastic, insightful comments, sometimes supported by references to the Teaching.

Sometimes it got so late at night that we just collapsed onto the sofas, dead tired. When I woke up, he was already seated at the table who knows for how long, back perfectly straight, writing down his dreams or practices for the Community (back then, he handwrote everything, and we photocopied it). If he made even a small error on the last line of a perfectly calligraphed page, he would glance at me with a pretence of resigned suffering, tear it up, and start anew.

Mig Mang and Mikado

I generally dislike board games and, unlike some of the older practitioners, never learned Bagchen, one of the Master’s favorites. But I had quite a ‘direct introduction’ to Mig Mang and Mikado. Playing with the Master wasn’t always ‘easy’, as veteran ‘Bagchenists’ well know: after all, playing with a ‘giant,’ always demands caution… The way he taught me Mig Mang, though, it’s almost impossible to play! He wouldn’t allow me to think for more than a second or two, but after the first instant he would already show signs of impatience. He kept repeating: “Don’t think, just use your eyes, the game’s name is ‘Many Eyes’ for a reason!” For someone like me, chasing his own head like a butterfly hunter, it was an impossible challenge. But I felt so unbearably pushed by his insistence that I eventually ended up playing almost without any thinking. Sometimes I had practically already lost, but he would turn the board around and still manage to crush me. Did I ever win? No chance. Only once I came really close (what a thrill!), though he still won. With an amused smile, he claimed he had never lost in his life.

Mikado was possibly even worse: the rules to touch and lift the sticks sometimes forced me to contort on the floor. His concept of a stick’s ‘vibration’ practically bordered on extrasensory perception! What fun, though… I have fond memories of those moments, especially with him and a still very young Yuchen, who once sent me into total panic about losing at Mig Mang to a little girl. I only won by a whisker: she was already absolutely brilliant! And who knows, maybe she took pity and let me win…

The Gift

Once, we were walking with Yeshi, who was about nine, and we passed by a shop window, possibly a toy store. Clearly already knowing what he wanted, he asked his dad if he could buy it. I don’t recall the item, but when the father asked him for the price, I noticed that it definitely wasn’t cheap. The Master stopped, and with a measured, almost theatrically majestic gesture, pulled out his large wallet, took out a hefty bill, and handed it to him.

As Yeshi rushed inside, I likely looked rather surprised, or perhaps was just savoring a moment I had never known, as my father died when I was very little. In any case, the Master turned to me and, in his usual expressive way that conveyed much more than words, said: “You see, you must do these things at the right time, or it’s too late.” In that moment, everything felt right and good.

The Administration Office

Another time I accompanied him to a separate administration office of the University, a run-down, almost squalid place. To me, being with him felt like walking beside a king, truly, and I found it absurd that he should laboriously climb the stairs to go into such a shabby place, and for what? Some trivial issue regarding payments, I think, with a lady who barely acknowledged him, replying curtly and dismissively, without showing him the slightest bit of respect. I nearly wanted to shout: “Do you even know who you’re dealing with? Do you know who this person is‽”And yet, he remained kind, completely unperturbed. But then, as we headed out, as always somehow sensing my feelings, he gave me a meaningful look and said something like: “You see? This is how things are… You didn’t expect this, did you?” No, I didn’t…

On the Train

Any simple, ordinary moment became extraordinary with the Master. Why? Because Chögyal Namkhai Norbu was at the same time the most special and the most simple person of all. Nothing stayed the same in his presence, an effect that at least I, but am sure many others, felt deeply.

Traveling with him was a highlight for me. We would take the bus to the station, and then board the train. He would get off at Formia, and I would continue to Rome. I would sometimes attempt small talk, with alternatively hilarious or disastrous results. I don’t know how he managed to be so patient and kind with me. Particularly early on, probably in reaction to my strong introversion, I was at times a little bit impertinent. And since I had no pedigree from any kind of ‘spiritual’ circles, nor was I particularly impressed by grand Vajrayāna titles, I was, let’s say, not overly deferential. And so once, when I was dying of boredom on the train, sitting across from him in silence for what felt like an eternity, I started a ridiculously childish game (I was craving some kind of exchange…). I pretended to be an imaginary random traveler and blurted out: “Excuse me, but are you Tibetan?”

I remember such moments from those early years very clearly, when I still had the courage, or rather a blind and naïve audacity, to play with the lion. In instances like this, the Master’s gaze would settle on me as if descending from unfathomable heights, his face carved in a monumental stillness that could literally terrify. But in an instant, everything would melt into a sweetness that, I now know, was shaped by compassion.

Playing along in a ridiculously squeaky tone, he answered: “Yes, I’m actually Tibetan! You are journalist…?” And with that, something in my mind short-circuited so dramatically, that it immediately and deeply taught me that playing with the king of games is no game at all.

Once we had not found seats and were both pressed against a corridor window. Since I had discovered it as a kid, I sometimes looked out of the window while rapidly moving my eyes in the same direction as the train’s motion. Normally, everything passing very close to the train, like poles, bushes, and so on, blurs into an indistinct streak. But when you move your eyes that way, for a very brief instant everything freezes, and you can see all perfectly still in front of you, as if the train were motionless. As I was doing this, to my utter surprise the Master looked at me and, without saying a word, gave me a very clear, emphatic nod, as if to communicate that yes, this was something that could yield ‘interesting’ results. I have no idea how he could have noticed that, nor did I ever ask him about it, but I felt I well understood what meaning he was trying to convey. With Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, everything could become Teaching.

A little scene I always remember, and have often recounted, is one where the Master had gotten off at Formia, and we (there was someone else with me that time) were leaning out the window to watch and wave him goodbye before he disappeared into the underpass. He was walking slowly, turning back and upward smiling and waving at us with his theatrical flair, when suddenly, horror! We saw that right where he was about to place his foot, on the next step below, there was an empty soda can. He couldn’t see it because he was looking at us, and we couldn’t warn him because it was too late and his foot was almost there. But suddenly, almost magically, a man appeared out of nowhere and, lightning-fast, snatched the can almost from right under his foot, a split second before what would almost certainly have been a disastrous fall. The Master realized what had nearly happened, and as we flailed our arms, making gestures as if to jokingly say “wow, what an over-the-top level of protection you’ve got‽”, he shrugged in his classic way, and we saw him bestow upon us his usual and well-known “Che ci posso fare…?” [“What can I do about it?”]

Many more episodes come to mind related to Merigar’s challenging early days, convivial amusing moments, ‘nighttime stories’, his famed Citroën Pallas, and many other glimpses of small-great moments I had the privilege to witness or to share as a student of such an extraordinary person. Then there were other decidedly non-ordinary events, which deserve greater discretion, as well as some that connect to the Master’s wide and profound cultural depth. But for obvious reasons of space, I have to stop here. However, I have one final thought to share.

Though these anecdotes may suggest a casual and friendly camaraderie with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, it is important to highlight that he was always and unquestionably the Master, whose immense intensity of inner energy was very powerfully present in every moment. Being in a kind of close terms through the years was nothing like being ‘friends’, because there was not even an instant when he unburdened himself by his role and commitment to be a guide for his students. Although this might seem obvious, I wish to emphasize it as a fundamental aspect of my experience, one that taught me how serious and total the dedication must be for those who are capable, and choose to, transmit the Teaching. It is also a renunciation of one’s own freedom and independence, with consequences that clearly extend to family members as well. In short, it is a sacrifice, one that spiritual realization does not make less present in its human and social dimension.

Far be it from me to craft narratives of hagiographic mythology, but this is simply my experience, and a small part of what I can gladly share.

Giovanni met the Master in 1978 at the University of Naples “L’Orientale,” where he was a professor of Tibetan and Mongolian. Over the years, he participated in the early activities of the Community, first informally, then taking on roles in Gakyils, and notably serving for many years as the director of Shang Shung Edizioni and various related activities. He lives with his family and works as a teacher and university researcher in Melbourne, and has been a member of the Australian Community for nearly twenty years.