During our last visit to Dzamling Gar, Adriano Clemente reminded me to write an article for The Mirror on how I met Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. I felt obliged and honored to follow this advice.

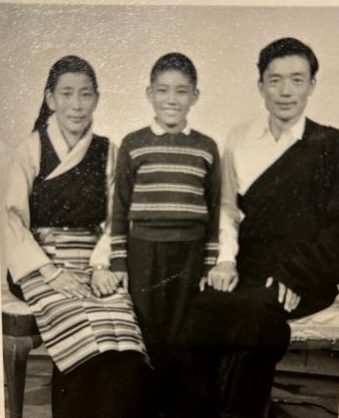

I was born on the 4th day of the sixth month in the Earth Rat year of the lunar calendar, the 4th of June 1948 in the Western calendar, in a place called Chödzong near Rongbuk monastery at the foot of Mt. Everest. My parents moved from Lhasa to this remote place due the birth of my elder brother who was recognized as the reincarnation of Zatul Rinpoche, the founder of Rongbuk monastery. My mother’s parents were from Kham and had migrated to Lhasa as traders. My father’s family was from Nyethang near Lhasa which is associated with the Buddhist scholar, Atisha and the Tara temple. Atisha was from Bengal, India, and taught in Tibet for 13 years. Nyethang Drolma Lhakhang was his residence where he died in 1054. This temple is also famous for the 21 Tara statues in it which are said to have survived the mass destruction during the cultural revolution.

My birth place, Chödzong, was the residence of our family while my brother was staying in Rongbuk monastery where he received his formal monastic education. Once a while, I also stayed in Rongbuk not only to keep my brother company but I also received my first education in reading and writing Tibetan there.

The monastery follows the Nyingmapa tradition and its founder was called Zatul Rinpoche. When my brother moved to Switzerland before the family, he said that his family name was “Zatul”, so after that all of our family members took this surname. However, when I write Tibetan, I don’t feel very comfortable with my name because of this “tul”, which means “incarnation”.

My family escaped Tibet in 1959 due to the Chinese invasion. I was eleven years old. After getting a tip from a family friend that the Chinese were on the way to arrest my brother and my father, who had been appointed as the administrator of this monastery by the Tibetan government, we had to leave our home in a hurry.

In some way we were very fortunate because at that time my brother was by chance in Chödzong, otherwise he might have gone to prison. And then when we left, we also had a second piece of good fortune because we met the yaks that belonged to the monastery. The yak herders told us to take them with us because at the border to Nepal we had to cross a very high icy pass which we couldn’t do with the horses, only with the yaks. And then, happily, up to the border to the Himalayas, we took the horses and the yaks, and from there we left the horses behind and went on with the yaks.

But even at that time we still didn’t know what had happened in Lhasa. We thought we would escape and after some months we would be able to come back.

In Nepal we arrived at Naboche, a small town in Solukhumbu, the place where mountaineers first come for expeditions to Mount Everest. The Nepalese soldiers who were stationed there told us that they had heard on the radio that there had been a revolt in Lhasa and that the Dalai Lama had had to leave for India. From that moment on we knew that we could not go back to Tibet any more.

In Nepal we stayed for a time at Tengboche monastery, which had a very close relationship with Rongbuk monastery, and then continued to India, to Dharamsala.

We lived in India until 1963. My brother was able to join a special training for young lamas and my two sisters attended the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. I was sent to a Tibetan school in Mussoorie. Our parents had a hard time making a living during this time.

Luckily, in May 1963 we arrived at Zürich airport among the second group of Tibetan refugees to be settled in Switzerland. The following years, more Tibetans settled in Switzerland. We now have a tight knit community of over 7000 Tibetans in Switzerland where we could pass on our identity to the young generation.

I was 15 when we arrived in Switzerland. I went to school there and eventually did commercial studies and worked about 10 years for a Swiss Bank, after which I changed to export import. So actually I had a normal Swiss life, nothing spiritual or a profession connected to Tibetan culture.

While I was working, I met many young Tibetans who were interested in the Tibetan language and I started teaching Tibetan to them. This was also good for me because while I was teaching, I also became interested in learning Tibetan. I was fortunate because the husband of my older sister was also a high reincarnated lama and I was able to learn a lot from him.

I first met Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche in Switzerland around 1971 at our home in a place called Ebnat-Kappel. Rinpoche came with his son, Yeshi, who was a baby, to visit Trijang Rinpoche, the tutor of the Dalai Lama, our guest at the time. What fascinated me was that Rinpoche changed the baby’s diapers. Seeing a high lama doing something so ordinary like taking care of his baby personally left a great impression on me.

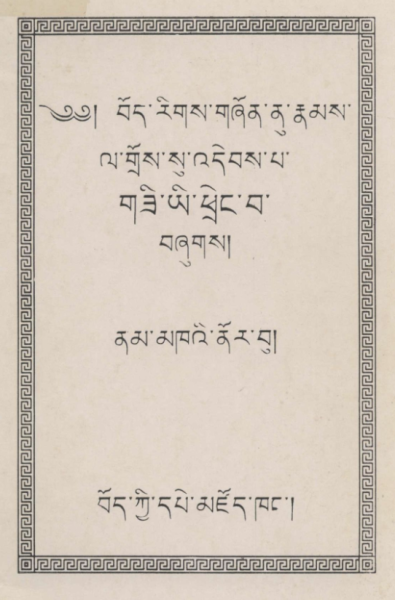

I was one of the founding members of the Tibetan Youth Congress in Europe. In April 1975, we invited Rinpoche to give a lecture on Tibetan history during the annual meeting of the Tibetan Youth Association in Europe. Rinpoche introduced his new book “The Necklace of Dzi (gzi yi phreng ba)” which he wrote for that occasion in Tibetan as a gift for us young Tibetans.

Rinpoche was a highly respected scholar both in and outside Tibet. Owing to his many years of traditional training in Tibet combined with his experience in modern research methodology in the West, Rinpoche acquired a deep knowledge of Tibetan history.

In that book, Rinpoche traces back his country’s history nearly 4000 years and refutes the almost accepted theory which reduced Tibetan civilization to the emergence of Buddhism in Tibet 1300 years ago. Rinpoche also rejects the account that Tibetans had no writing system before the reign of King Songtsen Gampo (d. 649). He considered that the Zhang Zhung Kingdom possessed a writing system that had developed long before the reign of King Songtsen Gampo.

The book was first published in Tibetan by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, in 1981. Noting the importance of this work for a wider readership, it was later translated into English and published by the Office of Information and International Relations, Dharamsala.

At the end of the event, Rinpoche said: “If any of you want to come, I live in Naples and you’re welcome to visit me.”

The following year, a friend of mine and I went to visit him in Naples. There, we met Rosa and their children, Yeshi and Yuchen. What I can remember is that young Yeshi was doing the Nine Purification Breathings in the morning and that impressed me a lot.

Rinpoche once took us to the countryside. We went to a vineyard where he bought a very big bottle of wine, a damigiana in Italian, and said, “Before you both leave, we have to finish this.”

Rinpoche was good at cooking, too. The Momos (Tibetan dumplings) he used to make were delicious. We would sit in the kitchen and drink wine while he was giving us teachings in an absolutely informal way. It was one of the happiest moments in my life.

During our stay in Naples, Rinpoche encouraged us to connect more with Tibetan culture. Once he wrote down the hundred syllable mantra for me and I promised to learn it before I left Naples. On the last day of our stay, I managed to recite the mantras by heart in front of Rinpoche.

We learnt from Rinpoche that he was doing the Tra divination. Since we were young bachelors at the time, we wanted to know whether we would get married. After doing the necessary ritual for the Tra, he consulted the mirror. For me, he saw three objects: a photo that looked like the Mona Lisa in a frame, a bridge and some flowers at one end of the bridge. And for my friend, he saw two dice with identical numbers 2 on them.

Traditionally, each one interprets the meaning of the Tra for oneself. At that time, neither of us could say what the meaning was.

Time passed by but I was always thinking about the divination. Then, a few years later, I met Kelsang, my future wife. While applying for her entry visa to Switzerland, Kelsang sent me her passport photo which I interpreted to be the Mona Lisa in the frame.

One day, my sister said that the bridge might refer to the ocean which was separating Kelsang and me at the time. That sounded quite reasonable. One morning, I had an experience between dream and reality which made it clear to me that the flowers on the other side of the bridge referred to the name of my wife: Kelsang Dolma resp. Kelsang Metog and Dolma Metog. I was convinced that this must be the meaning of the flowers Rinpoche saw in the Tra divination and it meant that I would marry a person with the name of flowers.

In 1987, we were invited by an American family to visit them in Florida. At their place, I saw by chance a magazine that mentioned Rinpoche’s book The Crystal and the Way of Light. I showed my interest in the book to our host who then ordered the book for me without my knowledge. What a surprise and joy! But, I had to read it a few times to get a glimpse of Dzogchen teaching. However, my interest started growing about Dzogchen.

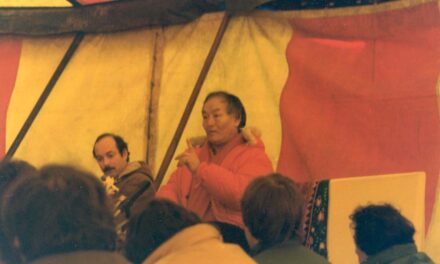

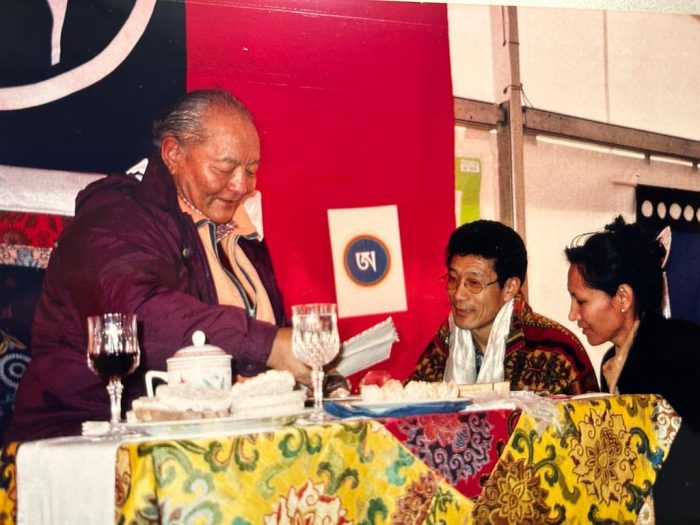

In early 1990, again during a meeting of the Tibetan Youth Congress in Switzerland, I read an article about Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche who would be giving a teaching on Dzogchen in Kandersteg, Switzerland. The retreat was organized by our late Christina von Geispitzheim who was living in Zermatt, Switzerland at that time. At my request, she arranged an extra teaching session for a group of Tibetans before the actual retreat started. Kelsang and I joined the group of Tibetans together with my mother-in-law who was a Dzogchen practitioner. We all felt so blessed to receive such a wonderful teaching from Rinpoche. Personally, I was so fascinated by Rinpoche’s presence and his words that I decided to stay on for the whole retreat. Christina later told me that she had never seen Rinpoche so happy and content after his teaching for the Tibetans.

When I heard the Song of the Vajra for the first time in my life in the presence of Rinpoche, I knew that I had found my Root Guru. E MA HO!