From Galenteen to the Lhalung Valley

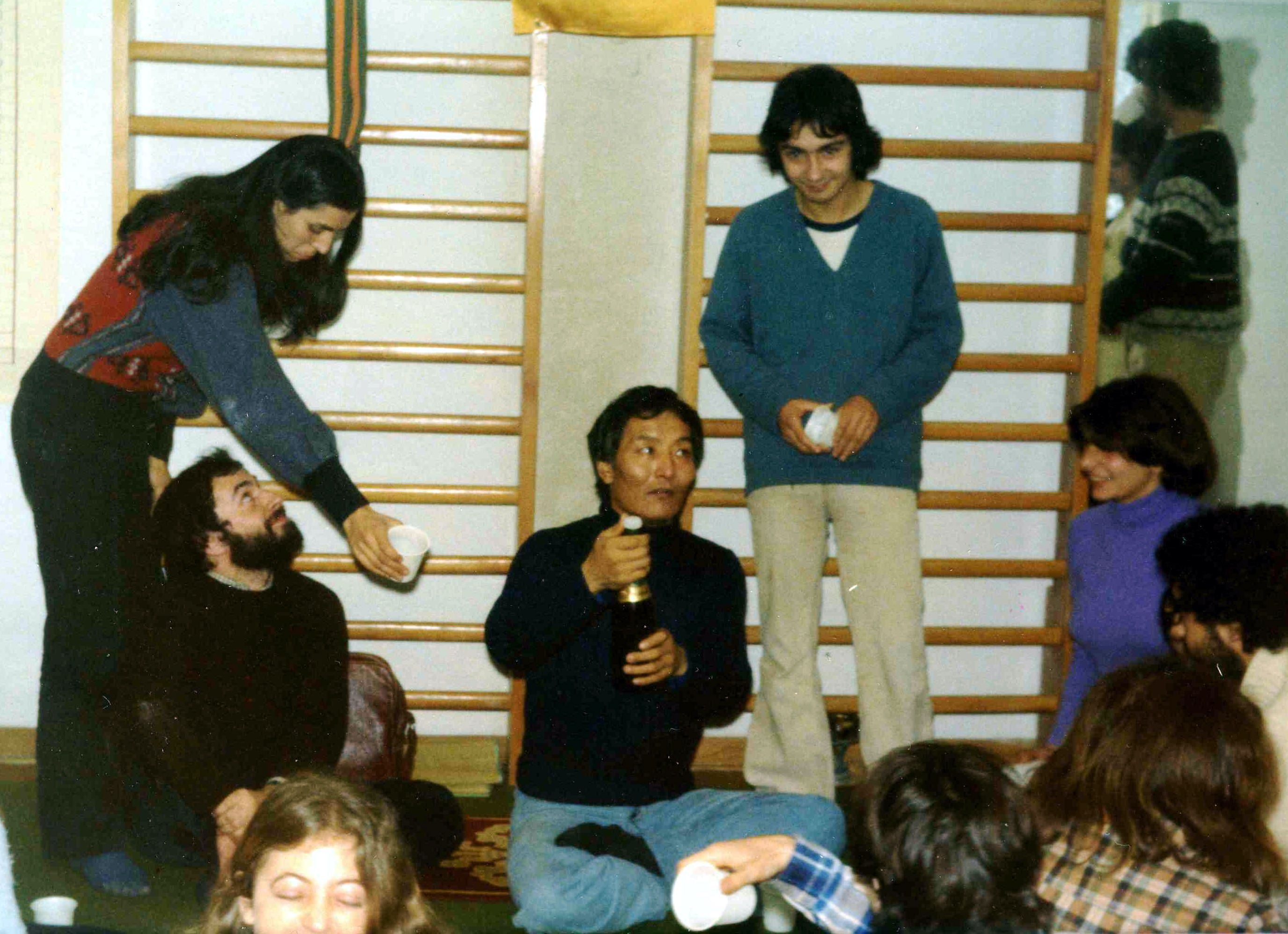

Raimondo Bultrini concludes the first chapter of his account of travelling in Tibet with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in 1988 from Galenteen to the Lhalung Valley and on to Gheug, the birthplace of the master.

The rosehip bush in bloom near the remains of the house where Chögyal Namkhai Norbu was born.

The morning chosen for our departure for the site of the famous terma [rediscovered treasure teachings ed.] discovered by Khyentse at the Yedzong rock, was cloudy and promised rain. Under the house a group of monks and lay people had already arrived to pick us up, including many of the riders who had won the horse races. We had to go north towards the Qinghai region and Rinpoche was made to get on a horse with elegant harnesses while I was offered more than one along the way, in a competition between our companions to show off the excellence of their mounts. At a place where the trails crossed we saw for the first time the top of the mountain formed by a large white stone and surrounded by fir trees where it is said Lhalung Palgyi Dorje lived for a long time, opposite another lower peak where Rinpoche’s uncle, Khyentse, often spent time in retreat. The master told me that they were sacred places due to the activities of numerous divinities and he would have liked to build two residences for spiritual retreats at the base of both.

Along the river we saw groups of Chinese gold panners who continued to scour the sand under the unremitting rain and we stopped to eat under one of the tents of a nomad camp where, despite the dampness, they had managed to light several braziers for food and sang [smoke offering ed.] in honor of the lama.

We crossed several rivers and streams on horseback where I followed the master’s advice not to lose my balance and to be aware that water flows downstream in order to avoid falling in. After seven hours we reached the first goal, at the foot of the sacred rock called Yedzog or Badzong, in a small valley hidden by some hills and known as “Inner Hat Mountain”. This was the place where his dream of the dakinis led Khyentse Wangchuk to discover the terma contained inside an object in the shape of a crane’s egg hidden in the rocks at a rather high point. Rinpoche had been part of the expedition to discover it back in 1951, after having heard the details of the dreams (described in the biography of “The Lamp”) directly from his uncle, and insisted on going there together. Our group was also accompanied by hundreds of people who crowded the valley at the base of the rock on June 15, a whole day on horseback from Galen.

The monks set up our camp in the rain and it was difficult to see the shape of the mountain tops right above us. In the meantime, we were housed inside the tents of the nomads surrounded by herds of bellowing yaks and monks to whom the master taught the rituals that he would perform the following day at the site of the terma. In the evening our tent was ready and, in spite of the incessant storm, we were able to sleep on the beds of branches that insulated our mattresses of saddle rugs from the wet ground. I felt a sense of enormous gratitude for that hospitality and the warm sheepskin jacket that one of them had been deprived of. I told the master that I felt sorry for our companions who were lying on the bare ground at the entrance to the tent with only one carpet and a blanket. Rinpoche said that they were very strong and devoted people and that they would stay all night to protect us from dogs and wild animals.

That evening he explained to me that above us, as I would see better with the light of day, there was a cave that had been visited and “empowered” by Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) and – opposite – the site of the terma, the Palace of the Three Roots, that had been revealed by the dakinis to his uncle in a dream. He said that it had the shape of the Tibetan letter A in the upper part and inside a strip of bright white rock where the container with five cycles of secret instructions was hidden. For the most part I brushed aside the deep meaning of that information but I asked the master how I could connect to the energy of those places, and prepare my mind to perceive their divine nature. He told me to relax and listen in silence, letting my thoughts vanish where they come from. As I wrote in my first account of our travels, I remained watchful and alert to every sound that seemed to transform itself into a mantra: the rain beating on the canvas of the tent and on the soft ground, the flow of the river below us, the distant thunder, the bells of the horses that were tethered and those free in the pasture, the regular breathing of the master who had fallen asleep and that night dreamed – as he told me – of the “energy of the local guardians”.

In the morning the rain had stopped and, after writing two pages of notes on the dream of which he did not speak to me as he usually did on other occasions, the master went up with a group of our companions to the point closest to the rock where his uncle had discovered the Yedzong terma. In my notes I mention my sadness for having already lost that fragment of the contemplative state I had experienced following Rinpoche’s advice. The magic of the night had passed and a heavy rain was beating on the tent where I was left alone to observe my thoughts.

What made me go outside was the always heady smell of the sang and the sound of horns, cymbals, and drums that announced to the local “guardians” the arrival of the master, accompanied by a multitude of Tibetans, at the site of the terma discovered 37 years earlier by his uncle. The rumor that Rinpoche was there, who at that time was at the height of the cave surrounded by Tibetan prayer flags under the site of the terma, had spread to the nomadic camps in the district and many of them also arrived there on that rainy day in June. They knew the fame of the place and the role that the 13-year-old Norbu had played in the discovery, excited to be able to participate in such an important expedition with his mother’s revered brother. His uncle had also shown him the scrolls with the syllables that he had received in a dream, the same ones found inside the rock in the shiny oval container where the text was preserved, and which later on vanished. The disappearance took place at the small altar inside Khyentse’s room, the same one where I had slept many nights, unaware of the facts, in a small bed next to Rinpoche. “My uncle said that it was the dakinis who decided not to reveal the content because the times were not ripe and there was too much turbulence in the energy of the place and of the people”.

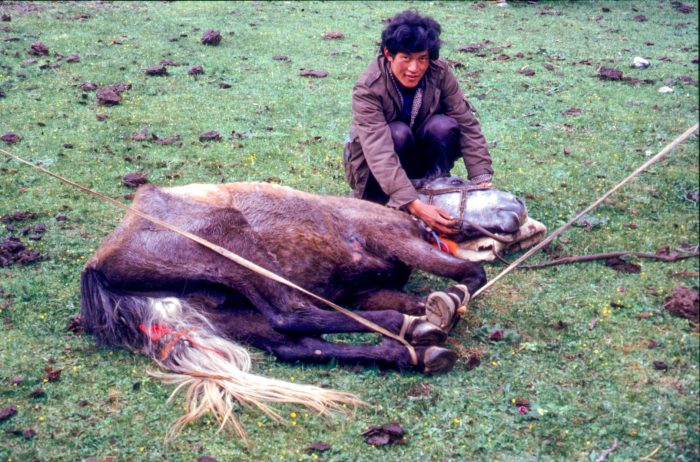

The morning of our scheduled departure for the cave where Lhalung Palgyi Dorje lived in retreat it seemed even rainier than the previous ones and I was a little worried. At the time Rinpoche took the two pages of notes written at dawn and, on his own with the assistance of a monk, conducted a ritual for the local “guardians”, the same he had evidently dreamed about the previous night. When at the end he gave the order to the caravan to proceed, the rain was not yet over and the master decided not to attempt to reach the summit of Lhalung, but promised that we would soon see another special place. There was only the problem of a horse that had a stone in its hoof and we witnessed the delicate work of extraction with a knife while the animal was tied up to keep it from moving. “Nomads love their horses as family members”, commented the master.

The horse with a stone in its hoof in the Lhalung Valley.

Finally the weather improved and we passed through an enchanting landscape of woods full of the intense scents of wild plants until the horses started running attracted by the vast plain that began to stretch out in front of us. It was the Lhalung Valley where, up to the time of the revolution, the ancient kings of Derghe came to spend the summer months, attracted by its rare beauty and unparalleled equestrian competitions. “The most beautiful place in the kingdom”, said one of them, as Rinpoche told me. Four or five young men showed off by racing their horses bareback with stunts that would have amazed anyone. We slept in a tent close to the woods and after visiting a family who offered us breakfast, Rinpoche recited mantras at the base of the rocks we were about to climb, crossing muddy ground under a lighter but more persistent rain. Once we were at the top the sun appeared among the clouds and illuminated the sacred valley of Lhalung and – in front of us clearly visible – the mountain of Lhalung Palgyi on top of which there was a large fir tree surrounded by a flowery meadow, like the whole expanse of grass below.

On the way back down the hill the horses slipped in the mud and the path was narrow. We noticed some rhubarb plants nearby and a meadow of regpà herbs – if I have written it correctly – a cross between onion and garlic. Here Rinpoche indicated one of the retreat places because – he said – he had discovered the ruins of a Bon temple with carved mantras, and would have liked to allow monks of this important pre-Buddhist religion to do the practice of their “protectors”, who had been largely integrated into the pantheon of Vajrayana Buddhism by masters such as Padmasambava and his disciples.

In the information he gave me that day – detailed in the booklet “In Tibet” published at the end of the trip – there were some historical and mystical details about the place known as Suko’s Country in the Su Valley (these are phonetic transcriptions), at a height of 3800 meters. The whole region – he said – was known as Waja Country, or Continent of the Waja lineage, the center of which was Galen. The mountain where Lhalung Palgyi took refuge after the assassination of the king was consecrated to Vajrapani, the original divinity, and to Manjushri and Vajrapani in their peaceful and ferocious manifestations. In a cave on that mountain slope the yogi had obtained the body of light, the same place where Khyentse Wangchuck discovered the image of Vajrapani, which – after the disappearance of the Yedzong terma – he gave to his nephew Norbu for safekeeping.

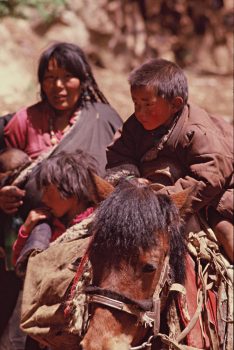

Mother and son nomads in Lhalung Valley.

Other smaller hills and valleys around us had exotic names such as the two main ones, the Valley of the Sun and the Valley of Heaven. One was called “the forest of the sentinels” from its triangular shape like “an eagle soaring”, another the “Mountain of the Valley of the Sky” formed by small round stones, another more simply “The Belvedere”, whose form – the master made me write – “represents the obtaining of the action of power”. The master said he would like to build a practice and study college here for 25 people that would be called Odzel or Radiant Light. At the streams where the cold water joined the hot springs that emerge from the subsoil Rinpoche wanted to finance a turbine to provide electricity for the college and the nomads so that it does not freeze in winter, one of the various public works that he thought would integrate religious schools and classes for the children of shepherds. “Now they grow like trees,” said the master, “without any education.”

In my notes, there are a lot of projects that have been written down but I do not know how many have been realized given the intervention limits imposed by the authorities, especially in times of great political tension. In the Valley of the Sun, for example, the master wanted to create a retreat house for only four Dzogchen practitioners to be instructed in the practices of trechöd and thögal in that solitary and generally sunny place where water and wood abound. Near the hermitage where his uncle practiced peaceful and wrathful manifestations he would have liked to create another retreat place for another four chöd practitioners, while near the summer residence of the kings he planned to reopen a nunnery that had already existed at the time of Lhalung Palgyi but was now completely destroyed. All the new structures would have been part – he explained – of the Practice College scattered on the edge of the “most beautiful valley of Derghe”.

We returned to Galenteen completely soaked and exhausted. I forgot about the lighted candle and woke up to the glow of the flame that sizzled in the melted wax. “Chinese candles” commented Rinpoche before falling asleep. In the morning I went to wash our clothes in the river and on my return found hundreds of small cords that had been prepared by the master who was already concentrated on repairing the namkha of a nomad that was broken. For a long time I watched the skill with which he always moved his hands until two local official “bosses” came to ask for one of these “protection” cords and offered a donation of 10 yuan, about a dollar and a half.

The next morning, June 20, Rinpoche had pen and paper brought and, without a break, wrote an invocation to Lhalung Palgyi Dorje and the story of the monastery of Galen as he had received it several times in a dream during the journey, even before entering Tibet.

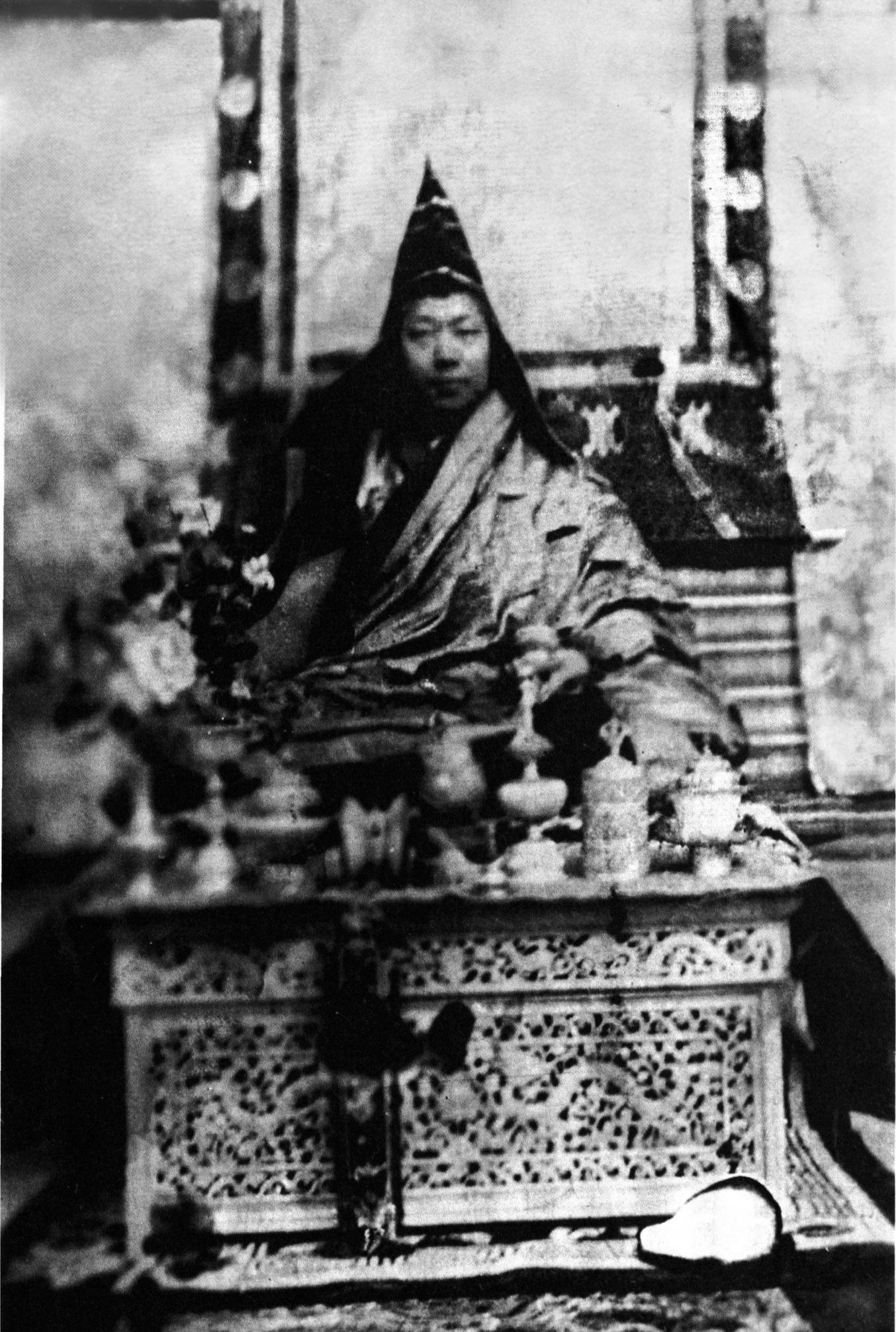

After the initiation of Avalokitesvara, which I have already written about, we left on another important expedition to the origins of the lineage of families that have made the history of these regions since ancient times. We were about to go to their cradle, the ancient kingdom of the Wagmo from where the master had his origins, descending from one of the branches of this aristocratic lineage and born in a place known as Gheug. But first I have to introduce people and places, again thanks to “The Lamp That Enlightens Narrow Minds” and the master’s biography of Ugyen Tendzin, who himself lived in long retreats in the same hermitages and caves of Lhalungar.

After the initiation of Avalokitesvara, which I have already written about, we left on another important expedition to the origins of the lineage of families that have made the history of these regions since ancient times. We were about to go to their cradle, the ancient kingdom of the Wagmo from where the master had his origins, descending from one of the branches of this aristocratic lineage and born in a place known as Gheug. But first I have to introduce people and places, again thanks to “The Lamp That Enlightens Narrow Minds” and the master’s biography of Ugyen Tendzin, who himself lived in long retreats in the same hermitages and caves of Lhalungar.

The Continent of the Wango

In the local dialect the word “Wa” of Wangpo and Wangchuk means “the hump” and came from the name given to the descendants of a family called Wamgo Tsan from a small village – where Gheug later arose – with only three people, a couple and their daughter who cultivated the land and raised goats. It is a long story told in “The Lamp” but in short, the daughter gave birth to a child with supernatural strength and intelligence, so much so that they called him Wamgo, divine son. He had a small hump on the back of his neck and was mythologized for having defeated enemy Tibetan armies and Mongols and receiving the Gheug valley as a gift from the kings of Derghe for himself and his descendants, a practice interrupted by the Chinese occupation.

It was among these descendants of the Wamgo that Rinpoche’s uncle Khyentse was born – as predicted before his death by Chokyi Wangpo – in the same valley hidden among the peaks of the mountain range overlooking the Yangtse River that was the cradle of many masters including Namkhai Norbu. When the day of his departure for the village of Gheug arrived, the master was still unwell with the after-effects of the flu that had kept him locked up for several days in his room in Galenteen, mitigated by a sang ceremony for the local “guardians” which he himself conducted. He said that many negativities from the past still weighed on the whole area, where even families of devotees had been seized with revolutionary fervor and subjected his uncle Khyentse – who accepted without batting an eye – and his elder sister Jamyang Chodron, a renowned poetess raised in the court of the king, disciple of Khyentse Wangchuck and other great masters, to torture such as having to drink the urine of “revolutionaries”. Jamyang spent 20 years mostly in forced labor and routine cleaning of cells in unspeakable conditions between 1959 and 1979 (I think Rinpoche met her in 1982, collecting her shocking testimony that was mentioned in “The Lamp”). Instead Sonam Palmo – the master told me – “had been luckier because she had been assigned pigs and chickens to raise and bred them in satisfying quantities for the Chinese, who in return made her life a little easier”. Even in Lhasa where she moved years later, her income came from herds, especially cows.

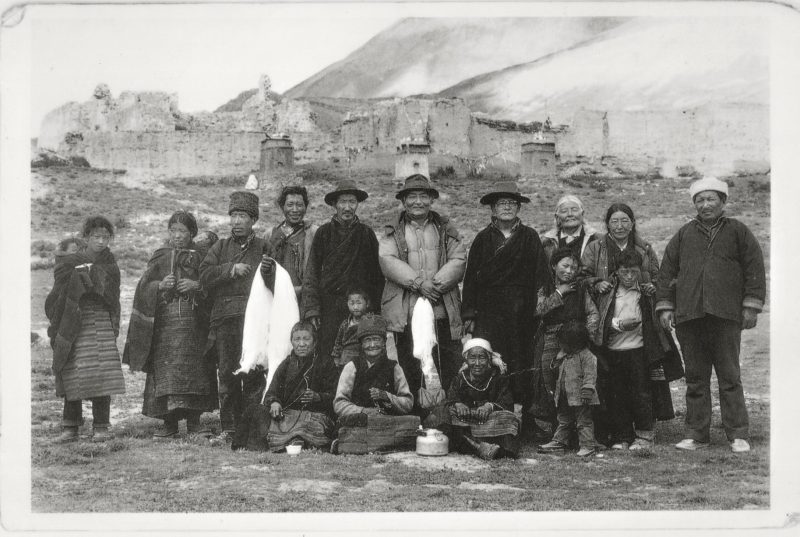

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu with his sisters at Ralung on the way to Mount Kailash in 1988. Photo by Brian Beresford.

One day among the inhabitants who crowded around the house Rinpoche pointed out to me two elderly women who kept their distance and seemed not to have enough courage to approach. I recognized the women who often followed me during the walks and meditations around the place where the locals had collected a large quantity of sculpted stones with figures of masters and deities among which some wind bleached lungta fluttered. One day – after many previous and fearful attempts – they got so close that I touched their heads to make them go away. I told the master about this episode and he was not happy at all. “Those pious women were two of the worst torturers among the activists. They had received numerous teachings and initiations from my uncle, then persecuted him to save themselves and did the same with many other practitioners. My sister was one of them, and I refused to forgive them when I returned to Galenteen years later and found them pleading and marginalized by the entire community. They know that they cannot approach me” – he added. “We cannot do anything for them because their karma of having broken the sacred relationship of samaya with their master in this way will not change with our forgiveness. I don’t think it’s very useful if you touch their heads, just to make them believe that somehow they have had contact with someone from the family of their victims”. It was one of the few direct reprimands I received, but I knew Rinpoche’s severe face enough not to envy Fabio Andrico, his most assiduous companion around the world. It goes without saying that these were mainly tests of presence in the front of a life teacher who was as demanding with his students as with his own children.

Expedition from Galenteen to Gheug (Gheogh)

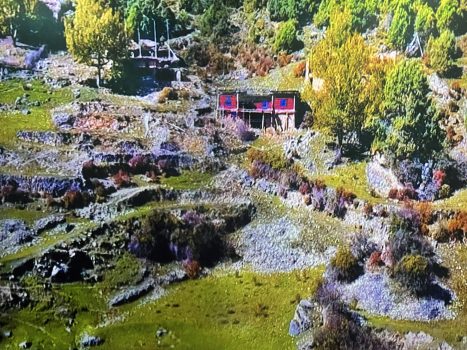

Gheug. Courtesy MACO 2016.

I was sorry that Rinpoche was not with us in the group of relatives who visited Gheug’s surviving family members, now semi-isolated from the rest of the world. His flu had resurfaced and he was advised to accept the hospitality and care of his family in the valley just beyond the Yangtse River, in the territory of central Tibet. After a transfer by car to the border between eastern and central Tibet, the master then continued with Phuntsok, crossing the bridge over the great river in that stretch that was not at its greatest extent as further downstream. It was Sonam Palmo who led me and the caravan of relatives and acquaintances who climbed on foot or on the back of horses and mules along steep stony paths that took us – without Rinpoche – to his village of origin. As soon as we got off our horses Sonam Palmo held my hands without words, except for those feelings of nostalgia that must have repeatedly manifested for her in the emotional involvement in the places of her own childhood and that of her brother, the tulku. For me they were also two intense days of wonder and sadness in that human outpost that clung to the mountain with a history so rich in legendary figures, despite the fact that they really existed, and miracles told by word of mouth, up to the time of those tragedies that were the occupation and the madness of the cultural revolution.

Approaching the village, Sonam Palmo pointed out to me a rounded rock like a white skull emerging from the forest of fir trees – that had not yet met the Chinese chainsaws – and which formed a dark and uniform mass at the base of the summit. The locals put their unwavering devotion in that place of the “guardian” Godrang and together with the others in our group Sonam threw prayer scarves and shouted invocations before resuming the journey with the increasingly tired horses. I offered to continue on foot since I was the heaviest of all, but I could only travel a few hundred meters due to the altitude which was higher than that of Galenteen and made the climb even more difficult.

Gheug. Courtesy MACO 2016.

When we got to a point just before the village, Sonam Palmo stopped the horses to show me a particular place, certain that I could understand. She simply said “Rinpoche”, pointing to herself and making a large circle with her hand that encompassed the few remaining stones of what was once their family home, known in the area as the home of the Norsangs. Tracts of the wall no higher than twenty centimeters were still visible and grazing grass covered them everywhere. There were two ruined buildings with the highest bricks and in front of one of these Sonam Palmo made me understand by her prostrations that it was the exact place where their mother Yeshe Chodron had given birth to the little tulku. “Rinpoche” Sonam Palmo said again, making the gesture of cradling a baby. Then she wiped away an emotional tear and from her chugkpa pocket took out a small box of tobacco that she loved to snort, for once without the reproaches of her brother who disapproved of it.

We met numerous descendants of the families who had seen the master’s birth and recalled the stories of the miraculous births of his uncle and his predecessor Chokyi Wangpo, all linked to the maternal side of the lineage. However, there were those still alive who had witnessed the arrival in Gheug of his paternal uncle, Togden Ugyen, with the announcement that the child was the reincarnation of his teacher Adzam Drugpa, who had died a year and a half earlier, leaving indications that corresponded to the characteristics of the son of his relatives on his father’s side. Drugpa had also appeared to the Togden in a dream, right in the house of the Norsang, and after prostrating, he saw him get smaller and smaller in the body of Yeshe Chodron. It was the Togden – the yogi who went down in history for realizing the rainbow body – who in his memoirs, collected by Rinpoche, wrote about the flowering in that cold December of the rosehip bush, still considered a true reliquary by the inhabitants of Gheug mostly related to the Norsang. Sonam Palmo pointed it out to me close to the remains of the former residence and I was able to photograph it in its natural flowering season at the end of May. (see attached photo)

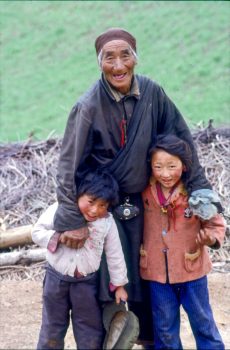

Rinpoche and Sonam Palmo’s elderly cousin from Geug with his grandchildren.

In one of the few houses in the village lived the extended family of the children of an uncle who had been killed by the fanatical revolutionaries because he was a “landowner”. Since then one of these cousins of the master had been paralyzed with psychic disorders and I was not allowed to visit him for fear that he would get agitated in the presence of a stranger. But I saw Sonam Palmo returning from the visit with tears in her eyes, as often happened in those days that were an immersion into extraordinary memories and intense suffering for her. With poignant emotion, I embraced another cousin of hers that she had not seen since the terrible days of the revolution, a man older than her and unsteady on his legs. One of the few people who remembered the days of Rinpoche’s birth and recognition by his uncle, we will spend many hours walking in the flowery meadows with with him and his grandchildren who ran around wildly and then returned from time to time to hug the legs of their old grandfather while posing for the camera.

In the room where we were guests they laid out two mats on the ground for us where we spent the night and in the morning we visited the upper part of the village from which the guardian mountain of Godrang could be clearly seen. The sky alternated between sun and dark clouds and with suspicious coincidence the water descended with large grains of hail every time I took out the video camera entrusted to me by the master to photograph it, until at a certain point Sonam Palmo signaled me to show my respect and put the camera in the bag. The heavy rain stopped.

Rinpoche left Gheug at the age of five after being recognized by many other masters including the Karmapa who considered him one of the three incarnations of the Bhutanese Dharmaraja, (the Shabdrung). He went to study in the castle of the king of Derghe who prevented him from going to Bhutan due to the risks he could have run in a country where the “war of the tulkus” and the political situation could take on dangerous implications, given that two of his predecessors had already been killed in the past. The family also soon moved downstream just beyond the Yangtse River which at that time divided – the Blue River in the east – the part under Chinese control from the western one that remained under the Tibetan administration of Lhasa, hence the Dalai Lama. It was here, in the village of Kuanto ‘(phonetic spelling) that we reunited with the teacher and Phuntsog, who had remained to assist him, together with other relatives, and help him recover from a very severe cough that had now almost passed.

This concludes the two parts of the journey dedicated to the masters who were also relatives of Norbu Rinpoche. Entering on horseback the valleys without passable roads in the direction of the capital, Qamdo or Chamdo (within the so-called “Autonomous Region”), we diverted even further inland towards the village of Changchub Dorje in Khamdogar. I hope to soon be able to describe this experience that led me to meet the community of farmer-yogis created by the master of the master whose body I saw preserved in salt before the consecration of the stupas that will contain his relics. Here I will limit myself to transcribing a passage from one of the most beautiful poetic songs composed by Rinpoche for those disciples of his root guru, practitioners with already profound knowledge of Dzogchen.

“All the various experiences are like flowers in a summer meadow:

The beauty of their colors is without deceit;

In the dimension of instant presence, like heat and humidity to them,

How marvelous is the spectacle of single taste!”

May the story of this journey be of benefit to the reader.

Editor’s note: The poem is taken from “Advice for Three Students of My Master” and is the third song “Advice to Lama Pema Loden”, Shang Shung Publications.

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988

You can also read this article in:

Italian