Raimondo Bultrini

For thirty-three years I have been meaning to recount my travel experiences with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu to other students of his. I already wrote a small booklet in Italian (In Tibet, Shang Shung Editions) immediately after returning to Italy in the winter of 1988 thanks to the editor of the Merigar magazine at the time, Cesare Spada. It contained some important moments during that journey, but it was too short and fresh to give the depth and charm of the details of a unique and now unrepeatable experience.

In the following years I transcribed – giving it the form of a travel book – the notes from my diary from the day of Rinpoche’s arrival in Beijing in mid-February 1988, invited to give a series of conferences for the National Institute of Minorities that would bring us from the Chinese capital in Chengdu, to Eastern Tibet and finally to Lhasa. I continued to transcribe notes and impressions until the end of the turbulent and extraordinary pilgrimage from the Tibetan capital to Mount Kailash together with about seventy other students, all more or less linked to the different Dzogchen communities around the world.

Raimondo in front of Changchub Dorje’s house at Khamdogar, where the Master’s body was still kept in salt inside a box. After the ceremonies with Rinpoche, the process of distributing the relics in the various stupas of the village began.

With age and fading memory the long typescript of the diary constitutes, I believe, an important document for myself and, I hope, for all the students of the Master, even if my intention when I wrote it was to address a general public so that many things may be obvious for those of you who are preparing to read some passages here.

Today the literary form of the story appears to me lacking in depth and I hope to be able to use it as a base and clean it up from the gross errors of transcription of names, facts and imprecise circumstances. However, I do not believe that certain shortcomings completely distort the meaning of what I have saw and heard, often from the voice of the teacher who for many months would be the only interlocutor and interpreter of what was happening around us, as the only Tibetan we knew were the words of the mantras learned by heart not always with a connection to their meaning.

This first piece that I offer to the readers of The Mirror, with the humility of a student who was culturally inadequate for the task of accompanying a master of knowledge like Rinpoche, will not concern the actual physical journey for now. Rereading my diary I found the transcript of a talk that the Master gave in Chengdu to young people and teachers at the Institute of Minorities with which I would like to introduce the sense of the “mission” that Professor Norbu carried out in those months of events which I was fortunate enough to attend.

Many of the things said will be known to anyone who has read his books or heard Rinpoche’s talks. But here they are aimed at young Tibetan and Chinese scholars as well as their teachers in order to deepen ancient history with a modern interpretation. Only by going to the root – I summarize the long message transcribed below almost entirely – can you understand the reason for the need to preserve Tibetan culture. But you should free yourselves from the idea of having the answers even before you have studied without prejudice, as every researcher should do. Practical invitations include studying English, a language that gives access to other types of knowledge needed to understand today’s world and counteracting the tendency to rewrite history and one day transform Tibet into a museum.

Researching Tibetan Culture

In 1988 during his travels in the East, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu was invited to give a series of conferences in various parts of China starting in Chengdu, then eastern Tibet and finally Lhasa. The following is a translation of the transcript of a lecture that the Master gave in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China, to young people and teachers at the Institute of Minorities. His talk introduces the sense of the “mission” that he carried out in those months of events.

Dear professors and students,

I am very happy to be back here with you after so many years. When I was young, if I remember correctly between 1953 and 1954, I came to this school for the first time to teach Tibetan and at the same time to learn Chinese. Some of you will remember because I see some colleagues among you that I knew at the time.

Many years have passed and the students of that time have become teachers, public officials and professionals. I am happy to be here not only for the nostalgia of those years, but also because I have noticed that everyone, both professors and students, have a deep interest in Tibetan culture and for what I personally had the opportunity to learn about in these years of research in the West.

We know that Tibetan culture is so ancient that it represents a value in itself, not only for our country and our people but for the whole world. At the international level, today everyone recognizes this value as a contribution to increasing knowledge and wisdom, first of all spiritual wisdom, but also civil awareness.

We have been through difficult times. For example, I was here more than thirty years ago. Then, for various circumstances, as everyone knows, I left Tibet and came to India. I didn’t have the slightest idea to leave my country permanently, but our lives also depend on circumstances.

I know there are some negative opinions about those who left. As for me, I repeat, the truth of the facts is quite different. What happened was not my intention. I never even imagined that I would have studied abroad and would have contributed in this way to the safeguarding of my culture. But, as they say in Tibetan, “A negative cause also brings good fortune”. Since in that year, 1959, the Tibetan government itself had abandoned the country, I couldn’t go back. So I decided to leave India, too, and look for a place where I could study and do something useful.

In this way I came to Italy where there was a famous scholar, Giuseppe Tucci, one of the first to be interested in Tibetan culture and to bring it to the Western world. He invited me to collaborate with him for two years, I accepted and left for this new country.

Fortunately for me at the Institute for the Middle and Far East that he founded, that professor had one of the largest collections of Tibetan texts in the world, possibly the largest. So I was able to read, study a great deal and work with Professor Tucci. Of course in the early years I did not read anything but Tibetan. I didn’t know Italian and the little English that I had learned in India was not useful as very few people in Italy spoke that language.

As you may know we Tibetans have many difficulties studying other languages. First of all the structure of our language is completely different from others.

Furthermore in Tibet there was no opportunity to study foreign languages. Even today, at such a distance in time, there is no Tibetan-Italian dictionary, for example. You have to use an English one.

Thus, with some sacrifice, I learned Italian. Of course the study of a foreign language is not limited just to language learning, but serves to understand the way of life of the country, its culture, knowledge and completely different customs. Those who always live in the same country may not realize this. However knowing other languages is very important and therefore today everyone studies languages in order to develop communication and to deepen their knowledge of the real world.

So I learned a lot by reading numerous Tibetan books on the one hand, and on the other hand seeing the world of the West, the way of thinking, of studying, and of doing research. And so first of all I realized the importance of culture. Before that I did not have very clear ideas on this point. I thought that the development of the economy, military strength, and the organization of government were fundamental for a country. But then, looking more closely at the life and development of Western countries, I understood that, although indispensable, economic and military development did not have the same importance for individuals as culture.

I saw that in the West primary school is compulsory for all citizens, and nowadays there is hardly anyone who has not attended primary school. For example, in Italy, not only primary school but also middle school is compulsory. This means that everyone in the West knows at least how to read and write and consequently has more ability to reason and understand at the intellectual level.

Therefore education is the very basis of the development of culture. And then, going deeper, I realized that the value of each culture is linked to the history of a country, of a people, and to its origins. I reflected on this a lot.

I have now lived more than half of my life in the West and it is probable that I will continue to live there. But I was born and educated in Tibet, so I have feelings and bonds with the culture of my country that are very alive and strong.

If there was a risk of it being lost I would not only be sorry, but I would do everything in my power to save it. And this is not only for me but certainly for all Tibetans, wherever they are, in India, in Tibet, in China. Everywhere all of us have this same feeling of gratitude.

But certainly nurturing a feeling is not enough. In some way it is necessary to act in practice, to do something to divulge and disseminate this knowledge, but above all to understand its value well. In this way I understood that I had to go back to the origins of Tibetan culture and discover its real value. After two years of working with Professor Tucci, the Oriental University of Naples offered me a position teaching Tibetan literature. So while I was doing my new job I also tried to follow the teaching activities and the conferences of other professors. This comparison was very useful for me and I thought about the fact that most Tibetan texts, at least the most accredited ones, are Buddhist. However, we

Know that before the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet there was Bon, the original culture, and that after the eighth century AD it was overlooked. It is the natural order of things that when something new arises in a country, everything that existed previously is considered worthless. It often happens and in Tibet it was like that. For this reason the study of our history goes back to Songtsen Gampo and no further. The origins of Tibetan culture related to the sciences such as medicine and astrology are traced back to India and also partly to China, totally ignoring everything that existed in Tibet before Songtsen Gampo.

But let’s look at things in order, starting with the origins of the Tibetan people. The history books we are talking about say that Songtsen Gampo was an emanation of Avalokitesvara. Since Avalokitesvara is a bodhisattva, therefore motivated by compassion, he would be the one to bring light to Tibet, a dark country without culture or spirituality, in short, a place inhabited by savages.

Some texts even recount that when Buddha Sakyamuni lived in India, more than 2500 years ago, there were still no human beings in Tibet. A bodhisattva, probably Avalokitesvara himself, standing in front of Buddha saw a light expanding from his forehead toward the Land of Snow. When the bodhisattva asked the Buddha to explain this vision, he replied, “It is a sign of the future. Your emanation will generate the population of Tibet which will subsequently follow my teaching and the light will spread throughout the country.”

Thus it was that, according to these texts, Songtsen Gampo, as an emanation of Avalokitesvara, invited the Buddhist masters from India and China, finally turning Tibet into a perfect civilization. And this is also the reason for the great devotion that the Tibetans have for the king/bodhisattva and his disciples.

But the truth is not quite what the books describe. We leave to those who believe in these things the question of whether Songtsen Gampo was or was not an emanation of Avalokitesvara. But from the historical point of view this was certainly not the main reason that pushed Songtsen Gampo to introduce Indian and Chinese knowledge in Tibet.

Before him there were at least thirty or so kings of Tibet, starting with the first, Ode Pugyal (Nyatri Tsenpo) who, living at more or less the time of Buddha Sakyamuni, certainly did not reign over an area without human beings. And from the time of that king up to Songtsen Gampo all the kings and the people followed and practiced the Bon religion. So it wasn’t a dark country as they say but there was a culture, there was spiritual knowledge.

Furthermore, prior to Ode Pugyal himself, in the territory of what today is called western Tibet, there existed a famous kingdom known as Shang Shung. This was the original kingdom of the Tibetan people, with its capital near Mount Kailash, and was divided into three areas: inner, central and outer Shang Shung. Central Shang Shung corresponded to the region of Kailash, where the capital was always based, outer Shang Shung to current central and eastern Tibet, while inner Shang Shung encompassed vast territories around the chain of the Karakorum and included some regions of the former Soviet Union, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Therefore it was an empire that was vast and mighty.

As for Tibet, in its beginnings it was a small kingdom that was a tributary of Shang Shung. In times when the methods of government were not like those of today, such a condition meant at the most having to refer to that distant authority which sent its representatives from time to time and demanded the payment of some tax.

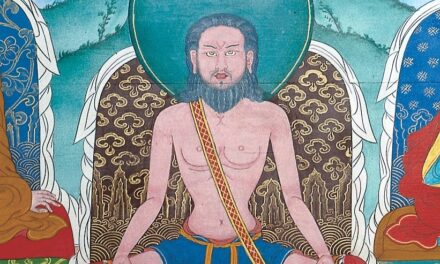

Historically, or going back more than 3890 years, Shang Shung was also the home of Bon. The master of the origins of this religion was called Tonpa Shenrab and his main supporter was a powerful ruler of Shang Shung, King Tri Wer.

Tibetan history begins at that time. There are in fact written records of the events and we know from that time that eighteen famous kings were on the throne of Shang Shung. Then Tibet was born which, albeit with a new name and other kings, was still dependent on Shang Shung, not only because, as we have seen, it paid tribute, but also because its cultural origins were the same as Bon.

And wherever there was Bon, there was also the power of Shang Shung in some way. Thus it was that, after seven Tibetan dynasties, some kings began to want to bring the power of the Bonpo priests under control.

In particular the eighth king of Tibet, Dri Gum, went into battle against these priests killing many and destroying the monasteries. But the country and the people all had their roots in the ancient religion and were loyal to its representatives. The king was assassinated by a minister before he had time to complete his project and in the end, things returned to the way they were before.

From the left Rinpoche, Alex Siedlecki, Cheh Goh, Keng Leck and Adi from Greece. © 2021 Namkhai Collection/MACO

Other kings tried unsuccessfully to eradicate Bon, until the time of the famous king Songtsen Gampo. He was a highly intelligent king and immediately established a series of dynastic alliances, asking for and obtaining as wives firstly a princess from Shang Shung, then one from Nepal – at the time, a kingdom that was a precious bridge of communication with India – and finally a Chinese one.

Songtsen Gampo’s plan was certainly not just that of taking wives or establishing diplomatic relations, but that of importing from their countries of origin the knowledge that would allow them to create a new Tibetan culture.

In the Buddhist version of the story, which is the official one, before Songtsen Gampo writing did not exist in Tibet. So one day the king sent his minister to India to learn Sanskrit and on his return both the writing system and the grammar changed. Hence Songtsen Gampo was considered to be the savior of Tibet and the bearer of civilization. But the truth was not exactly like that. A writing system existed and had been in use for some time throughout Shang Shung, including Tibet, but the king wanted to create an alphabet that belonged entirely to his reign. Today a script using capital letters and called uchen is used in Tibet while the ancient script derived from Shang Shung is used in italics.

It is therefore clear that, although a form of writing existed, the Buddhists preferred to imply that it was a king of their religion who invented one and gave it to the Tibetans. In this way Songtsen Gampo nevertheless succeeded in his purpose. He brought Buddhism to the country by inviting masters from China and from India, thus creating a new culture that took the place of the old.

This choice certainly contributed in a decisive manner to developing and completing Tibetan culture, but by attributing all the credit to India and China, he made the mistake of ignoring the value of the native Bon tradition.

However, it was actually Songtsen Gampo who was the first to control the power of the Bonpo priests, while later on one of his successors, Trisong Detsen, invited the great master Padmasambhava and the learned Santaraksita, built the temple of Samye and eliminated much of the Bon tradition of that time. Trisong succeeded positively in this endeavor of his because he did not simply destroy but gradually replaced, created and developed the new Buddhist culture.

The era of Songtsen Gampo was finally marked by another important historical event, the end of Shang Shung. It was in fact annexed to Tibet after Songtsen Gampo killed the king and not even the name of the former powerful empire remained.

This is the story that explains why Songtsen Gampo brought Buddhism to Tibet, not because a religion didn’t already exist, or because the country was in the dark, inhabited by savages. There was rather a specific political motive.

I think it is very important for all of us interested in Tibetan culture to understand all of this. Because a culture like ours, whose origins go back more than 3890 years, has a historical value that is not inferior to those of cultures such as the Indian or Chinese. And the history of a nation that has existed on this Earth for such a length of time cannot be ignored because it represents a world treasure.

If we don’t understand all of this people will continue to consider only the folkloristic aspects of minority nationalities and ethnic groups, without considering the value of their culture. It shouldn’t be like that. A profound knowledge that has existed for four thousand years, that is still alive and is passed on is something great and important and cannot be lost.

There are many cultures on earth and certainly all of them have their own particular value and must be safeguarded. But how many of these cultures contain universal values? Take for example, the theories on the origin of man in Tibet. When they speak of man’s origins many Tibetan scholars claim that, according to ancient Bon, everything arose from the cosmic egg. Other scholars laugh at this theory and consider it to be nonsense, while still others claim that the principle of the cosmic egg is not originally from Bon but was borrowed later on from Hinduism and Shaivism.

If a scholar supports certain theses right away everyone is ready to believe him or her. Why? Because they think that Tibet is a little place that may have its own culture, but certainly not the history and the value of the knowledge acquired by other older and more important nations. Even if Tibetan culture was the most original traditions these scholars always ask themselves: where does it come from? From China or India?

Let’s go back to the example above. Thinking about it, even if it were true that the theory of the cosmic egg comes from Shaivism, one must always ask about the origin of Shaivism itself, which in the sacred texts of this religion is located on Mount Kailash. But where is Mount Kailash? It is in Tibet, certainly not in India. More precisely, it is the heart of the ancient kingdom of Shang Shung, the homeland of Bon. Hence, Shaivism, and all its theories, come from the Bon and not vice versa.

Of course this is just one example. But if we think about it many other similar cases can be found. If we do not think, we do not give any importance to these aspects that are linked not only to the knowledge of general concepts, but above all to the values of existence. Let’s take another example. It is said that, as human beings, we have a physical level, but also a mental one. The mental one is deeper and more difficult to understand.

Regarding this aspect, in the tradition of the Bon there also existed the Dzogchen teaching, a term used in ancient times to define the Bon of the pure mind. It is such an important teaching that in Buddhism, in Tantrism, the finality of knowledge is considered to be Dzogchen. Therefore, if, three thousand years ago, there was already such a profound interest in the nature of the human mind, comparable to a philosophy, one can better understand the great value of this culture.

But the culture of a country is tied to the people. If the people do not apply it and do not live with this culture, if it exists only as intellectual knowledge, you can understand that, more or less, it’s a dead culture. I say this to you students because you have come here from different areas of central and eastern Tibet, from Qinghai, from Kansu, from Yunnan, just to understand more deeply these aspects of our culture, which I hope you will develop through study and research. And it is important to do this research with an open mind. Do you know what this means? It means that a researcher doesn’t have to necessarily belong to or be against a religion, or consider oneself an atheist, a materialist. If someone is conditioned by these limits he or she is not carrying out serious research. Doing research does not mean limiting oneself, or trying to learn more about aspects that can be justified by an ideology that has already been established.

A few years ago I happened to see many Tibetan books printed in China and Tibet, especially texts from the Buddhist school. Somewhere I always found written: “It has been decided to print this book even if it does not follow the principles of materialism … “. This is like officially establishing that everyone must follow the point of view of materialism.

On the political level I do not know what to say and maybe it can be justified. But this cannot be the approach of those who want to do research. Research means reading, studying anything, be it Bonpo, Buddhist, or ritual. It doesn’t matter where it comes from if it helps to discover what the truth is. And in the Western world, many real researchers have achieved important results by applying this method, without setting any limits. So I hope you do, too.

The value of man is that of being free, and being free he applies, seeks and distinguishes between good and bad. Those who know how to do research probably know how to find their own identity as individuals, finally.

I hope you are able to continue on this level, study and deepen [your knowledge]. With this wish I greet you and hope to meet all of you again.

Featured photo: Namkhai Norbu (right) walking through Chengdu with his sister, Sonam Palmo, in 1988. © 2021 Namkhai Collection / MACO

You can also read this article in:

Italian