I was born in Leningrad, finished high school there and then graduated from the Faculty of Art and Graphics of the Pedagogical University. So my first education qualified me as a drawing teacher.

I dreamed of becoming an artist, was interested in Buddhism, and from school I read everything that could be found in Soviet times on the topic of spiritual practices. In the seventh grade, I found a samizdat book (an underground publication in Soviet times – ed), began to practice hatha yoga and immediately fell in love with it. A little later I read that the remnants of Buddhism in our country are preserved in Buryatia so, in 1985, I travelled to the Ivolginsky datsan near Ulan-Ude, where I came into contact with a Buddhist spiritual tradition.

Meeting with the Dharma. Buryatia.

My first teacher was the oldest monk of the datsan, who out of respect was called “grandfather Dharma Dodi”. He was one of the few lamas who had survived the October Revolution and gone through all the persecution and repression. He had been educated before the Revolution and, by coincidence, had spent many years in the Stalin concentration camps in Kolyma and therefore knew the Russian language and culture very well. I received the oral transmission of teachings from him and immediately began to practice.

When I saw Buryat thangkas for the first time, I was shocked because when faced with thangka, you lose interest in other art. While I had been studying at the art institute, I wanted to paint everything, portraits, still life, and many other things, but once I saw the thangka, I no longer wanted to do anything else. It is the supreme art, the art of Dharma, which surpasses everything.

At first I tried to copy thangkas. I drew from books that could be obtained at that time, old Buryat editions with black and white images. It seemed to me that it was simple: I am an artist so it is enough for me to make a tracing paper copy. But I was faced with the fact that it was impossible to do this without understanding the technology. You can make some kind of design based on Green Tara, but it still won’t be a thangka. I found that thangkas have a special charm, a special energy, but to catch that quality is very difficult. When people see a real thangka they are fascinated by it and have a strong desire to do the same piece for their personal practice.

I understood that to master the art of thangka you need to study seriously but in Buryatia in the late 1980s there was nowhere to study and no one to learn from, although now, many years later, I know that there was an exceptional artist called Danzan Dondokov and his daughter Lyuba Dondokova, who adopted his style.

Dharma in the Soviet Union

The first lama to come to the USSR was Bakula Rinpoche from Ladakh in North India. He came to Moscow in 1989 because he was the Indian ambassador to Mongolia and at the time the Soviet Union had the warmest relationship with Mongolia. His lectures were somewhat secret and information about them was transmitted among those interested in Buddhism by word of mouth. The teachings took place at the library and it was a breath of real Dharma.

Then, in 1990-1991, the karma kagyu tradition came to Russia with the monk Rinchen from Poland, who taught ngondro, and then Ole Nydahl with his wife Hannah, their first teacher Tsechu Rinpoche, the “transparent lama”, and the monk Kalsang.

Meeting Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche

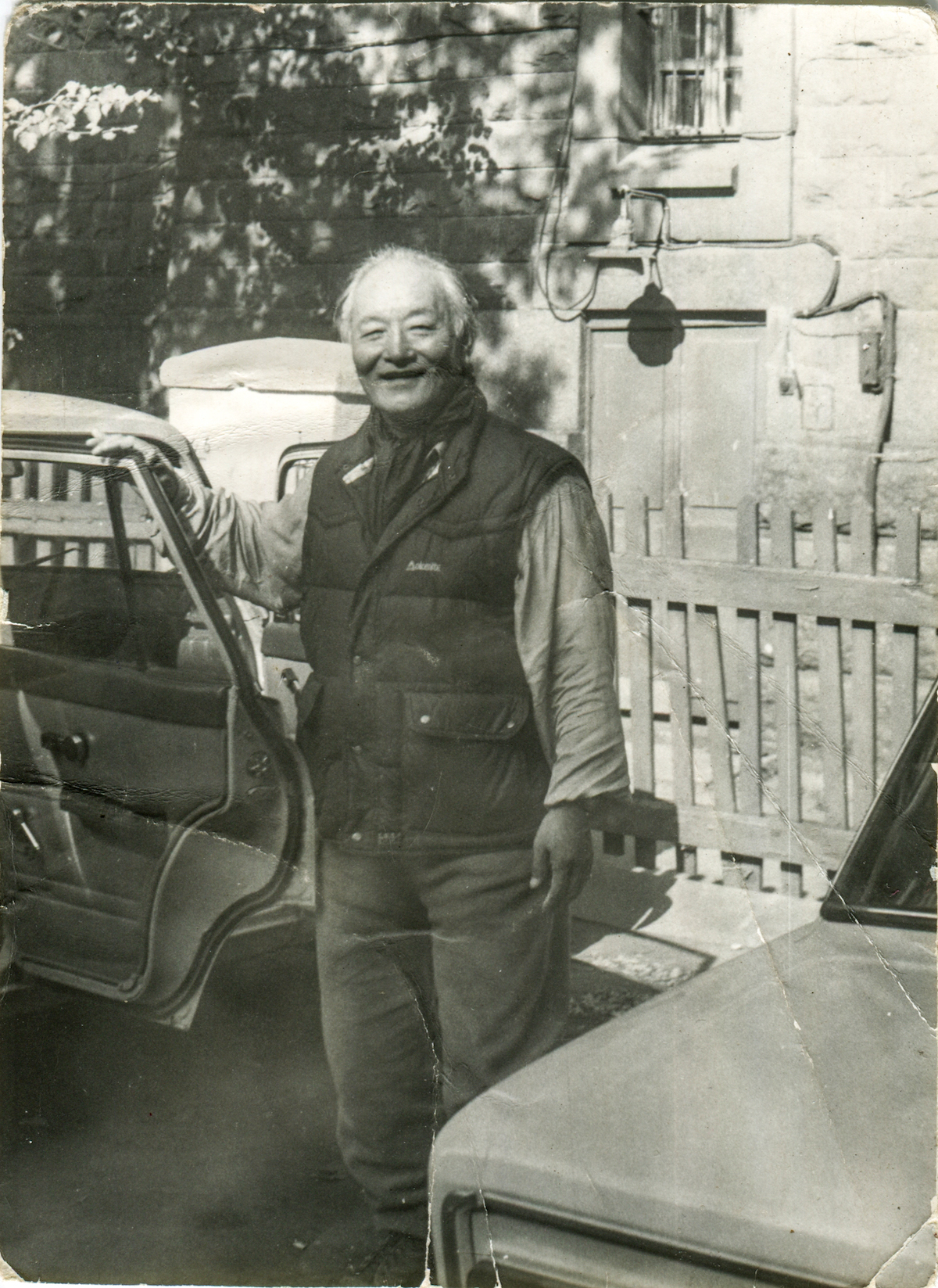

Later in 1992, Namkhai Norbu came to my native St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad). I took the subway, drove to the datsan, where the first two lectures were held, and saw Rinpoche for the first time. It was wonderful. Rinpoche drove up in a very modest, by today’s standards, rare car, Moskvich-411. He was dressed European style, a little sporty, but not like a lama. He was giving a difficult lecture on the nine vehicles in the nyingma tradition and I sat and listened as if spellbound. At the same time, I realized that I did not know even a third of the words that he uttered, but I decided to learn them later.

That year Rinpoche’s retreats were held in Vilnius, Leningrad, Moscow and Ulan-Ude. Rinpoche came to Russia with about fifteen of his disciples. It was June, the datsan had thick stone walls, and it was cold inside. Apparently, Rinpoche’s closest disciples knew the nine vehicles of nyingma, and, wrapped in blankets, they fell asleep. At some point, a funny event happened: Rinpoche shouted deafeningly “Padmasambhava! and everyone, startled, got out of their wrappings. For some reason, I remember this moment very well. For me, the lecture was not boring, it was a little stressful, as I did not understand some of the words, but I tried very hard.

There was another funny moment at the end. After the lecture, people began to approach Rinpoche and each said something of their own. Among them there was one man who asked endlessly: “Still, I didn’t understand how Milarepa managed to hide in the yak’s horn?” He repeated: “Please explain to me, how could it happen? Surely Milarepa cannot fit in the horn!” Rinpoche laughed as if he were being tickled and his laughter echoed through the datsan. The more Rinpoche laughed, the more this man asked.

The next day the lecture continued and on the third day the retreat was moved to a school building in a remote area of St. Petersburg. Further teaching took place in the school gym and everything was just magical. There was enough room to spread the mandala and there I saw the Vajra Dance for the first time. Only a few of Rinpoche’s students knew the dance but many people tried to repeat something, standing around the mandala.

Then circumstances developed in such a way that I easily and without hindrance traveled further to Buryatia and in a couple of weeks I went to a retreat not far from Ulan-Ude on Lake Kotokel. At the second retreat, Rinpoche’s teachings were perceived more strongly, precisely and, on my part, consciously.

After the retreat, I lived for some time in Vladivostok in the Russian Far East, where we formed a local Dzogchen Community. There were several people who had received the transmission, and we formed a small group, studied the practices and did one retreat after another. I can say that I did not notice the “bold” 90s (difficult times after the collapse of the USSR with a lot of instability, criminality, poverty, etc. – ed): I was busy all the time with practice, retreats and related plans. In June 1993, we did a retreat on the chöd practice in the Sayan Mountains in Buryatia, and in general, for a year we studied and performed retreats on all the practices transmitted by Rinpoche.

Thangka. Education.

In 1994, at the invitation of the karma kagyu center, a thangka-painting artist, Mariana van der Horst, came to St. Petersburg. I was lucky to be able to study with her and at the same time translate that retreat. Classes lasted about ten days, after which I firmly decided that I wanted to go to study in India. Learning from Mariana was great and later I translated many of her retreats in 1994-2015, until she stopped traveling due to covid. But at that moment I realized that it was necessary to study for a long time, seriously and thoroughly, and decided to find a teacher in India.

I was ready to set off for my journey, but in 1994 there was an outbreak of cholera in India, restrictions were imposed and in the end I did not go anywhere. In 1995 we heard that there would be Santi Maha Sangha exam and retreat and since this was a priority for me, the trip was again postponed.

In 1996, a retreat on the first level of Santi Maha Sangha was held in Zhukovka, near Moscow, at the residence of the former general secretary of Mongolia. It was an absolutely wonderful retreat with just over a hundred people participating. These were people who had just passed the exam and some of Rinpoche’s closest students such as Fabio. During this retreat I managed to go to Moscow and took ticket to Delhi and back for a year.

In 1996 I flew to India. Thanks to the tremendous blessing of Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, circumstances came together magically. But in addition to going there, it was necessary to find a teacher in India. I knew English and only that India was a third world country, as they used to say, that’s all.

India. Eternal love.

A wave of blessings immediately took me to the Kalachakra initiation given by His Holiness the Dalai Lama at Tabo Monastery in the Spiti Valley in northern India. From that moment on, somehow everything started to develop. Soon I met my teacher Ngawang Dorje, head of the School of Thanka Painting for the People of the Himalayan Region of India in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, called “Painting in Gompa Style”.

He had received a traditional education for lamas at Kundeling Monastery in Lhasa, where he was sent at the age of 6. There he also became a thangka artist in the gadri style. In the early 1950s, he went on foot to India and became an Indian citizen. The teacher said that I could learn from him as much as I could so I studied with him for three years from 1996 to 2000, periodically leaving India to get a new visa. The easiest way was to travel to neighboring Nepal and thanks to this I met many wonderful masters and was able to do retreats in holy places permeated with Dharma blessings.

Kunsangar. Return to India.

In 2001 I finished a Mandarava thangka and went to a retreat at Kunsangar. The thangka was hanging behind Rinpoche for the entire teaching and at the end of the retreat I was chosen to join the Kunsangar Gakyil, so until 2003 I lived and worked at the Gar, dedicating all my free time to painting. During that period, I did the Green Tara thangka, which I offered to Rinpoche during the Green Tara retreat. Later Rinpoche presented it to Kunsangar South.

After 2003, I came to India to see Ngawang Dorje whenever I could. Besides, I began organizing pilgrimage tours to the holy places of India and Nepal and, as a result, I lived there most of the time until 2020. I was particularly interested in the geographical “places of power” associated with the practice, with our line of transmission. For almost 20 years, I have organized and conducted many creative trips and pilgrimages, always linking them to the teachings. Especially memorable were two Mandarava practice retreats with Dzogchen Community practitioners at the Maratika Cave in Nepal in 2017 and 2018. The second trip coincided with the period after Rinpoche’s passing and we dedicated a retreat to his memory, consecrating the Mandarava thangka there with the whole group.

Creation of a thangka. Technology.

When creating a thangka, sometimes a sudden inspiration comes to me and I immediately sit down to work. When a thangka is ordered, then I plan my time and carry out orders, for example, in winter. Everything is done slowly and unhurriedly.

The thangka has a very strict technology developed over the centuries. Traditionally paints from ground minerals are used as they give a very beautiful velvet surface. These are the colors of the spectrum that convey the pure energy of the five primordial elements.

First, the canvas is stretched and then primed and polished. Then a drawing is applied, colors are superimposed, and where a transition from a saturated color to a lighter one is required, toning is done. The glue acts as a connecting link; on the glue base, coating is made with chalk or clay. Paints are also mixed on with the glue base and, when applied, become part of the canvas, a single whole with it. Then it’s time for brush strokes. Every detail is stroked with a thin brush by making flexible soft lines with pressure. Lastly, finely ground unpolished gold is applied and then everything is polished with a precious stone tip. Sometimes a drawing is applied by polishing. The softness or hardness of a stone such as jade or amethyst makes a difference in the intensity of the shine.

Reflection in the mirror

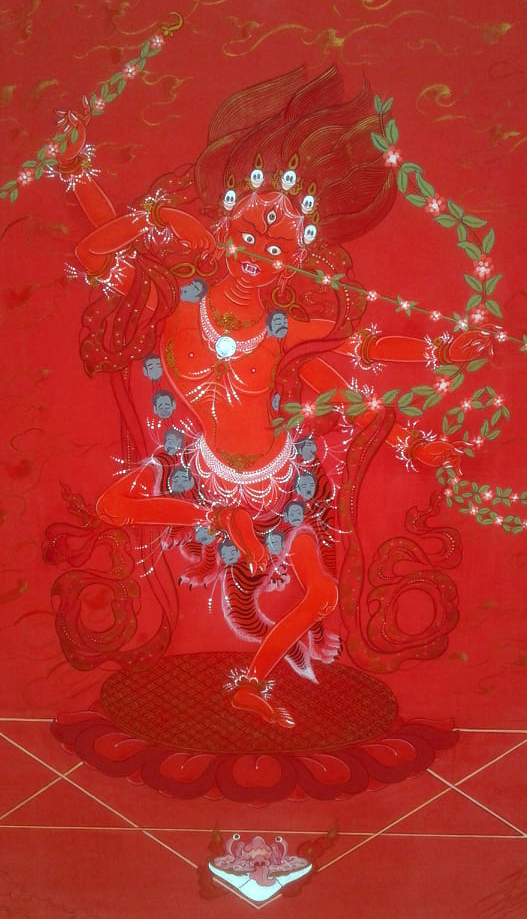

A thangka represents the ideal dimension, the pure land of the Buddha. The surface of the thangka is called ‘mirror’, or melong in Tibetan. The elements of the landscape are arranged according to the art of organizing surrounding space – Tibetan geomancy, or sache.

There are special techniques when a thangka is written in gold on a red background – martan, on a black background – nagtan, and on a gold background with a red outline – sertan. They are associated with visions at the time of death and such a thangka is a cause for postmortal liberation.

The thangka non-verbally transmits the meditation sadhana. It fully describes the deity, its state, its qualities and transfers its energy by means of painting. A thangka serves as a support for practice and helps to collect two accumulations – merit and wisdom. A good thangka leaves a very strong imprint on the mind, so it also serves as a cause for liberation. In addition, a thangka can be used as a magic ritual. If you need to perform an action, to achieve what you want, then one of the methods is to order a thangka. For example, to help the patient recover faster, they traditionally order a thangka of the deities of long life, for example, White Tara. I know that one monastery ordered a thangka from my teacher Ngawang Dorje to find the rebirth of their tutor.

Ritual of consecration of a thangka (ramne)

If possible, it is better to empower and sign the thangka with a lama. When I empower the thangka myself, I do a ganapuja, and then in front of the corresponding chakras I put down the seed syllables behind with red simdhura or gold.

Practical lessons in thangka painting

For several years I have been doing Buddhist thangka art retreats at Kunsangar North. Usually it is on Friday and at the weekend, after which the participants do their homework for four days, and the next weekend we meet again. Hopefully in the future we will continue our studies!

Larisa’s contacts:

Whatsapp: +7 911 725 95 30

Email: lararoj24@gmail.com

You can also read this article in:

Italian