On the Road to Nyaglagar

Raimondo Bultrini continues his travels with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in 1988 to reach the village of Rinpoche’s root teacher, Rigzin Changchub Dorje.

The previous episodes published in The Mirror of my journey accompanying Chögyal Namkhai Norbu to Tibet in 1988 were a synthesis of the diaries and writings that I worked on in the months and years following our return to the West. However, this episode and those that follow are the more or less exact transcription of the long unpublished story transcribed at the end of one of the most significant stages of that pilgrimage to Khamdogar, or Nyaglagar, the village where the root master of Namkhai Norbu, the great yogi Changchub Dorje (1826-1961?), spent the last decades of his long life.

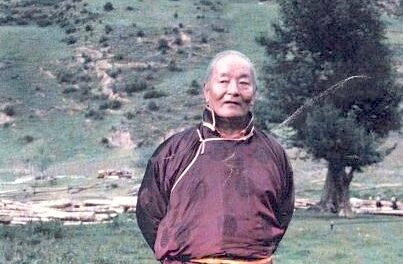

He was a disciple of Adzam Drugpa (considered a previous reincarnation of Norbu Rinpoche), Nyagla Pema Düddul, Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen, and Drubwang Shakya Shri. According to a text that Nina Robinson wrote on Namkhai Norbu, https://melong.online/our-masters-masters-rigdzin-changchub-dorje/, Changchub Dorje “was born in the village of Dhakhe in the Nyagrong (nyag rong) district in South-Eastern Kham. His mother, Bochung (bo chung), was originally from Dege and was a disciple of Gyalwa Changchub (rgyal ba byang chub), a highly realized yogi from Khrom. He founded his community of mostly lay practitioners in a remote valley in Konjo in eastern Dege. It was and is still to this day known as Nyaglagar and also as Khamdogar. It was in 1955 that Chögyal Namkhai Norbu met Rigdzin Changchub Dorje following a dream.

“The first time I met my Teacher Changchub Dorje – said Norbu Rinpoche – I was a little surprised because his appearance and his way of living was just like an ordinary village farmer. He wore very thick sheepskin clothes and big, thick sheepskin trousers because it was cold in that country. Until then I had only met very elegantly dressed teachers; I had never seen or met Teachers who looked like that. The only difference in his appearance from a normal village man was that he had long hair tied up on top of his head and conch shell earrings and a conch shell necklace.”

My story of the days spent with Rinpoche 33 years after his extraordinary experience in Nyaglagar remained in a drawer for a long time due to my fear – still undiminished – of inaccuracies and superficiality in describing the intensity and depth of the relationship between Rinpoche and the master who introduced him to Dzogchen, and the extraordinary nature of a remote place in Tibet literally transformed by Rigzin Changchub Dorje into a community of believers that is unique in the world. My attempt was to describe facts and circumstances with the simplicity of a journalist, my profession for decades, and I attribute to myself every misinterpretation of the same explanations received by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in those days and months of this extraordinary journey backwards in time.

When we finally reach the main road, our young guide offers me his bicycle to get to the village of Kuantò on the other side of the river. We pass a checkpoint on the bridge that separates Sichuan from the autonomous region. A Tibetan soldier with an old machine gun on his shoulder looks at my passport and permit, while a small group of curious locals gathers around us. The bridge is quite long and there are military sentry boxes on both sides that seem empty.

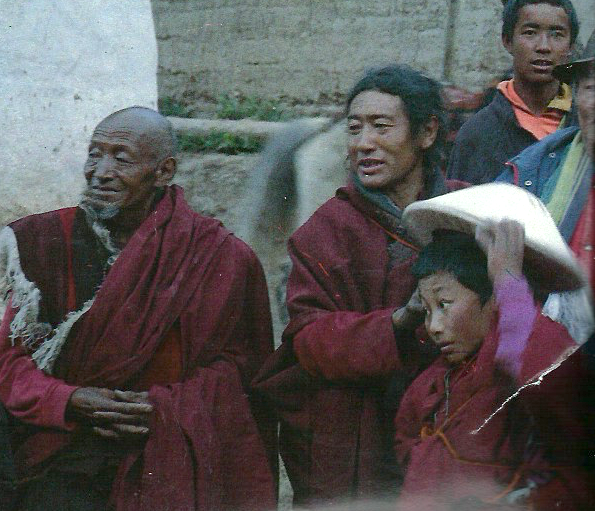

The monks at Nyaglagar with Changchub Dorje’s grandson, Karwang, on the far left. Courtesy of the MACO.

We soon arrive in Kuantò where – as usual – the Chinese houses are isolated and surrounded by fences, while the Tibetan ones are lined up side by side along the banks of the river.

Passing through the usual inquisitive crowd, along muddy streets and parts of the village that look African, we arrive at the house that has hosted Rinpoche and Phuntsok the last two days. Namkhai Norbu is still ill and his cough almost prevents him from breathing. On the other hand I now feel good, strong, and finally a little calm. It is the very idea of being on a journey, waiting to reach a place which I can’t even start to imagine that excites me, mind and body. Perhaps the continuous physical movement stops thoughts from gathering for too long on the same point, on the anxiety of living, thoughts that I haven’t been able to dissolve in my tiring meditations.

I’ve been hoping to wash in the river, but I have to give it up again this time because there is little time. I haven’t taken a proper bath for almost a month, even if the consequences are fortunately not so terrible at these altitudes. We leave the day after our arrival passing through landscapes of narrow valleys slashed into the sides of the mountains until almost suddenly boundless plains open up, ending in snowy mountain chains. We are now traveling above 5,000 meters on the No-là pass where the black tents of the nomads stand out in the snow. Namkhai Norbu talks of having crossed this pass many times, but in very different conditions, with days and days of riding on horseback.

Coming down the other side, winter seems to end all of a sudden, although patches of snow and ice still catch the eye among the colors of the spring grass. The figures of two men moving along doing prostrations are visible against the whiteness of the frozen countryside. They are going to Lhasa, and they will arrive exhausted, at the limit of their endurance, if they are able to hold out.

Why do they do it? The only sure thing is that faith is stronger than their own lives. They want to arrive in the holy city, and they kneel praying on every stone along the way. For them, every step on the way is an offering to the gods, to the masters, to the Teaching. No material comfort, a car to get there first, wealth, nothing is important for the purification of such a sacred and painful journey whose final goal is realization.

I ask the master if this sacrifice will really serve any purpose. “With such a strong intention – he replies – they will certainly get what they want.” I remain silent for a long time while I see the two pilgrims who have now stopped to observe us disappear in the distance. I, too – despite the different stages of the journey – am going to Lhasa but there is a big difference between their gruelling path and my easy journey in jeeps and planes.

The animals of the highlands

We pass through the capital, Jonda, where many Chinese live and we come across others piled into trucks, heading for some quarry, or along the road under construction. A few kilometers from the capital are enough for us to not meet another living soul. The grass turns moss green and the earth is red. They look like the colors of a savannah, only more intense, while any human population has been replaced by all sorts of wild animals.

A hundred meters from us a wolf runs and pauses when we stop the jeep to take photos. He watches us for a few seconds then shies suddenly and runs away. Two huge vultures soar above us while everywhere, from one hole in the ground to another, run the small avra, a species of mice that often carry tiny birds, the atakayu, on their backs. When they run into the holes, the birds fall. I observe the scene with the feeling that it may hide a meaning. By remaining present, moment by moment, we can ride time, without chasing or anticipating it. Any distraction by hanging on to memories, to hopes or fears for the future, makes us follow the fate of this tiny bird.

The avra also have another characteristic – they are used by Tibetans for their symbolic moral anecdotes. In fact, this mouse accumulates a lot of straw in the summer to eat in the cold season, and it heaps up enormous quantities of it with great difficulty compared to its size. Often, however, other larger animals, having discovered the burrows, devour all its reserves in just a few bites. This small rodent thus represents the futility of the effort to greedily accumulate wealth for oneself when chance can take everything away.

Finally, the avra – who live in perfect symbiosis with the atakayu, so much so that they can even be transported in flight if necessary – are also famous for the network of their tunnels similar to those of moles. There are areas so infested with avra that they remain completely barren.

However, the real masters of these places are actually the crows. They are everywhere and they are enormous. For Tibetans, these birds also have another symbolic meaning beyond the apparent one: they are the manifestation of the protector Ekajati, a female entity surrounded by flames who protects the Teaching by flying from one point in the sky to another. She only has one eye which symbolizes non-dual vision, and to have an idea of its form the Tibetans adorn their altars with peacock feathers: the eye is the colored concentric circle.

The few nomads we meet have a wild look. The women and children have long straight hair sticking out in all directions, while their skin has the red color of the earth. After half a day of travel by jeep we reach a village of semi-nomads who live in red stone houses at the end of a dirt track.

A austere man with long hair neatly tied back comes to accompany us to a white tent with embroidered designs, where groups of monks, children, and onlookers are waiting for us. Our companion is called Karwang, and is one of the grandsons of Changchub Dorje, the founding lama of the village of Khamdogar. To reach the village that the master of Namkhai Norbu also called Nyaglagar we have to travel three more hours on horseback across streams, down steep descents, and along very narrow paths, since there is no road and not even the jeep could make it. For this reason Karwang and the monks have come to the appointment a day early and with horses for everyone.

The horses that we will ride plus a couple of mules for the luggage are tied up around the travel tent, where we take a break and sit in a circle for the butter tea ritual. That is the way our caravan will move across another stretch of paradise that has never known cars, nor Westerners.

Riding a horse in places like this certainly offers a totally new feeling of harmony with nature, but also of unreality. What I am seeing and touching right now is not as fantastic as my thoughts about a world where there are industrial fumes, missiles, stress, traffic. The rare villages along the road are made up of stone houses that look like small castles set against the rocks. We follow the path of a river transparent like glass, where the water runs so smoothly that it looks like a motionless sheet of glass that lets light reflect on the stones at the bottom.

As always, the landscape changes at every turn and I can observe everything with ease because a young monk skillfully holds the reins of my horse, leaving me free to enjoy the landscape. Here too, the Khampa learn to ride at an early age, even before they know how to stand on their legs, and the young equerry monk smiles at my funny style of trotting.

Along this route there are no nomad tents, but scattered houses, from which men and women come out to greet us. Someone senses that there must be a great lama, and approaches with head bared to obtain a blessing. A short way from Nyaglagar, two auspicious signs announce the arrival of our party. An eagle spins in circles above our heads and a cuckoo sings non-stop somewhere in the valley. The cuckoo song in particular is considered one of the most auspicious signs.

At Nyaglagar

The low-pitched sounds of the long horns and drums and the high ones of conch shells and trumpets get louder and louder as we approach the village, while wisps of smoke from the rising clouds of sang appear here and there beyond the last gorge that hides the valley of Nyaglagar. Here, too, the offering of sacred aromatic herbs spreads a sweet and acrid smell throughout the area and all the senses can converge in one fantastic insightful sensation. The valley opens up behind the last curve revealing a triangle formed by a river, a forest of fir trees, and a mountain. The sky is crystalline blue faintly mottled with puffs of light clouds and also seems bounded by the same triangle of this valley.

The place immediately has a very different feeling to Galen. Nature seems to welcome us with its best mood, a good climate, intense colors. Crossing a wooden bridge we enter the village where there is a grand welcoming committee. Namkhai Norbu receives the homage of the khatag and is given another horse to ride. Now the music of the monks playing on the temple roof is thunderous. Along the dirt road that leads to the central part of the village there is a line of huge white chorten, survivors of the Cultural Revolution. Together with the chorten, two almost intact temples and the ruins of others destroyed by years of forced abandonment define the perimeter of Nyaglagar, with its fifty or so houses and dozens of natural caves where yogis and practicing Dzogchen hermits still live today. With the small video camera I try to capture the whole surprising spectacle as the village welcomes us, the crowd following Rinpoche’s horse and opening the way to let us pass, curious and smiling.

Finally we are here, in this place, perhaps the most awaited of all destinations. I have heard so much about Nyaglagar and the legendary Changchub Dorje that I have the thrilling feeling of being able to touch a dream. And actually the stories of the masters and disciples linked to Nyaglagar seems to have arisen entirely from dreams. Namkhai Norbu was little more than a boy when he told his parents about his vision of a Tibetan village where a man lived in a Chinese-style house where there was the mantra of Padmasambhava. From the descriptions of a traveler friend of his father, who spoke of a great doctor well known beyond the Yangtse, he recognized the man and the village of the dream, and asked his father to accompany him there.

Today there are only a few more houses than in 1956. For the rest, nothing has changed, not even the house of the founding lama: the same objects, the same bare rooms, the same white walls. Even the old hermits have come down from the caves above the village to see the lama who has come from the West, and someone recognizes the eighteen-year-old tulku who was a disciple of the great master, more than thirty years earlier. The steady stream of visitors begins as soon as we set foot in the temple hall where we will stay for a couple of weeks.

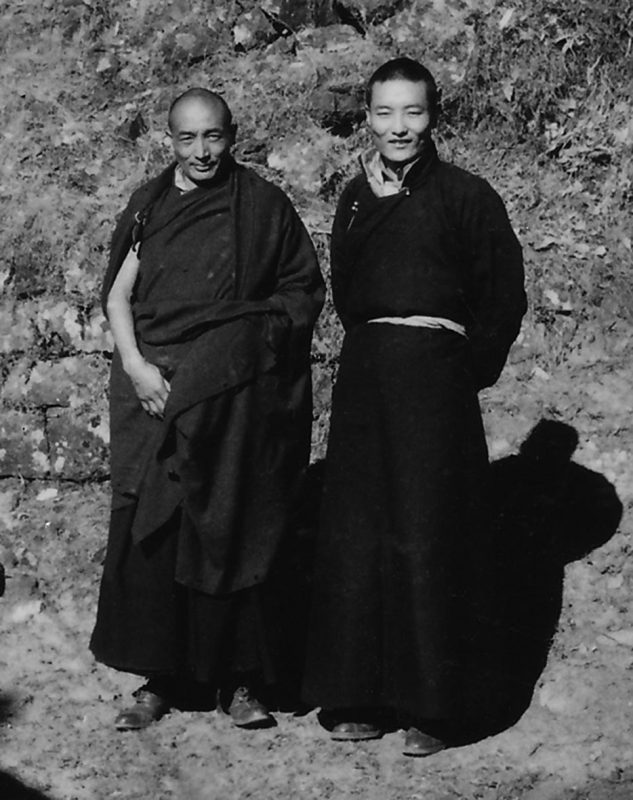

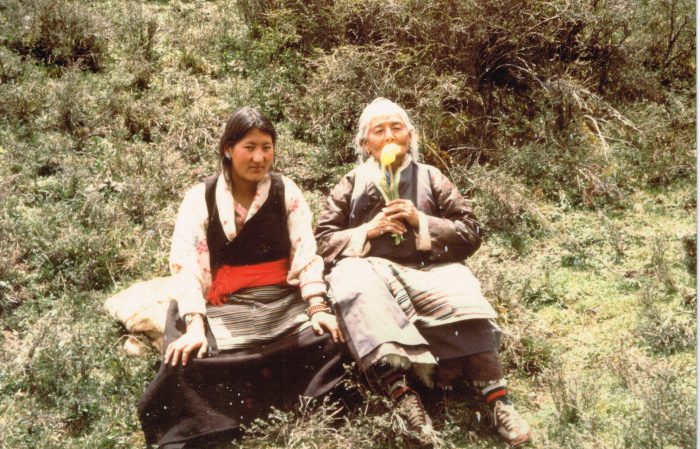

Phuntsog Wangmo (on the left) and Rinpoche’s older sister Sonam Palmo during the journey.

Sonam Palmo, Phuntsok, and I sit on the carpets that will be our beds while a large bed is reserved for Norbu Rinpoche at the back of the room, in front of a small altar surrounded by 108 niches with as many statues of Padmasambhava. The visitors offer white scarves and kneel before the lama in the usual slow ritual. They wait behind the door for their turn and someone prostrates along the way to the lama’s throne bed, adorned with colored silks. I have to work hard to say “no” to all the people who continue to offer me butter tea, tsampa, dried meat, biscuits, sweets, and rice with meat. I’ve learned to say “Enough, thank you” and sometimes, but not always, it’s the magic phrase to stop the flow of food.

Sonam Palmo is not very happy with me because I refuse the food offerings too often. I know it may seem offensive behavior, but I really can’t manage to eat and drink everything that appears in front of me and Sonam Palmo’s insistence irritates me for the first time, like a child forced to do something he doesn’t want to. Tsampa is difficult to impose on those who are not used to it because, especially in the first days, it makes the stomach swell up and is not very digestible. Not to mention the roots of the to-mà, which are so rough that it is difficult to get them through the esophagus. The only way to get them to their destination quickly is to dress them with yogurt. But it is a good idea to eat at least half of them with dried tsampa and butter, a deadly mixture. It must be said that this dish is considered a real delicacy, and certainly after a long period of training it can be appreciated in its right flavor. Fortunately, at Nyaglagar, when it comes to food, there is no lack of choice, because the stream of people who come to pay homage to the disciple of Changchub Dorje consists of farmers and shepherds, and no one enters empty-handed.

Faces surprised or intimidated, men, women, and old people of an incalculable age, each with their “mala” in hand, recite mantras as they approach Namkhai Norbu’s bed. The lama seems to have no expression, and before my eyes his figure has now transformed into that of a king revered by throngs of subjects.

At the end of the procession, the monks and the leaders of this community of three, four hundred souls remain in the large room lit by candles. They sit at the foot of the bed of the lama, who talks continuously. I catch the names of places: America, Australia, Japan, Europe, Italy. Also here Namkhai Norbu is obviously talking about the mysterious West and the countries he traveled to before arriving in this realm of the Dharma.

I try to relax waiting for the night, when we will be alone in the room again. They bring me a pile of blankets and I understand that the time has now come. The guests leave us, bowed and moving backwards so as not to disrespect the lama by turning their backs on him. After midnight the long deep-sounding trumpets sound twice and the slow, steady beating of the drum begins for the night ritual of the guardian deities, called to protect the sleep of the village and its new guests.

Before dawn, the low deep sound of the horns awakens us again to remind everyone of the presence of the lama who was a disciple of the great soul of Nyaglagar. Listening to the story of Changchub Dorje as Rinpoche has described it and as the inhabitants of Nyaglagar continuously talk about it, it is hard for me to find their portrayals exaggerated.

To be continued in the December issue of The Mirror

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988

You can also read this article in:

Italian