Raimondo Bultrini continues recounting his travels and experiences with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet in 1988. At Nyaglagar, residence of Rinpoche’s root teacher, Changchub Dorje, the Master leads a puja to consecrate the chortens and Raimondo searches for a cave from one of Rinpoche’s dreams.

Consecration of the Chortens

Namkhai Norbu’s visit to Nyaglagar is an exceptional event for many reasons. First and foremost is the role of a ‘reincarnated’ figure in the culture of the Tibetan people. The ‘tulku’ is somewhat related to the deity himself, and his presence alone blesses places and people. Furthermore, at Nyaglagar, Namkhai Norbu is one of the most important disciples of the founding lama. That is why they ask him to consecrate all the chortens and places of worship with long ceremonies.

Form and ritual have their importance because even if they are invisible, guests have been invited into the house. It is therefore a good rule to offer sweets, liquor and food in a proper way.

Thus the ceremony is preceded by a puja, a banquet that follows rather particular procedures, given the exceptional nature of the guests. The puja is another ritual that is characteristic of Eastern religions, during which offerings are first presented to the deities and higher beings, then to oneself, and finally to the lower beings and all others whom one intends to benefit.

Video by Raimondo Bultrini. Video and screenshots courtesy of the Merigar Archive

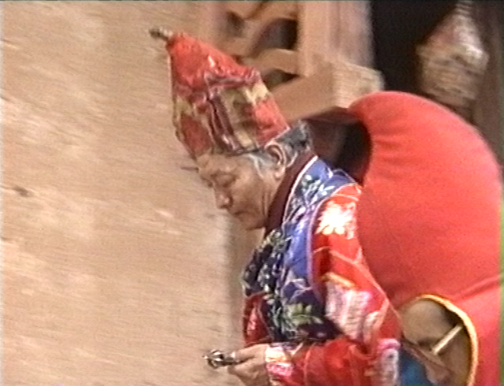

Thirty years later, Namkhai Norbu is offered the clothes and objects of his master in order to lead the great puja that begins early in the morning. The visits to our room thus become more frequent and faster.

The preparations all take place over time. On an altar lit by hundreds of butter lamps, the torma offerings are ready, moulded forms of tsampa, butter and sugar in the shape of cones, to which small balls of butter alone are added, giving the torma doll-like shapes. In this way they symbolically replace the human and then animal victims that were once offered to the deities in ancient times. There are also simple foodstuffs like rice, meat, sweets, and liquor.

Everything is authenticated by mantras at the beginning of the ceremony, but I do not take part. Namkhal Norbu is adamant: “There is no point in your presence, you cannot even read the texts”. In this case rituals are fundamental, because through gestures and intentions the offerings are destined to beings who cannot enjoy them in their material form. A slightly risky comparison can be made with the food and the wine of the Christian liturgy, but only as a principle of transformation, of transubstantiation from the material offering. And this requires precise practices, formulas of communication between beings that speak different languages.

When I reach the temple, a wing of the crowd that has not found space inside opens up to let me sit in the great hall of frescoes. The interior has completely changed in appearance from previous days; on one side nuns and practitioners are sitting, on the other the women gather around the widow of Changchub Dorje’s son, Sonam Palmo and Phuntsog.

They chant in low tones, interrupted by the high-pitched notes of trumpets and conch shells and the beat of the damarus and drums. Every so often Rinpoche, assisted by Karwang, sprinkles the offerings of sweet wine, which is then distributed in the hall. Each person takes a sip and pours the rest over their heads, intending to nourish body and mind with the nectar of purification, previously offered to the deities.

Suddenly the ceremony stops and there is a commotion in the temple. Namkhal Norbu, Karwang and the other lamas are changing clothes and the focal moment of the day has arrived. The procession of officiants is coming out to consecrate chortens and temples. With my camera I film the crowd that has already poured out into the open and I also take a few photos. There are a lot of children, naturally curious, who want to see the video camera and the camera, but, respectfully, they don’t touch anything. One of them, who has proudly offered to help me with my bag, turns around and follows me around silently.

In the meantime, monks and lamas come out of the temple door in a line, make a clockwise circle around the building and do the same with all the chortens scattered around the perimeter of the village. People crowd into the streets, climb up the earthen mounds, go down to the river, follow the procession and precede it. This ceremony has some vague outward resemblance to a Christian procession, but everything around it is Tibet and Buddhism: the sound of horns and drums, the furnace where they burn the food offerings of the ganapuja and those brought from people’s homes. The procession stops in front of each chorten and the lamas toss grains of rice and water while chanting mantras. I run along the narrow streets to get ahead of the others and film with my video camera, followed by the little boy with the camera bag over his shoulder. I’m exhausted by the time we reach the last stop in front of the largest chorten, where the relics of Changchub Dorje will probably be placed in the future.

A long chant begins, accompanied by the sound of instruments. Rinpoche is now in the center of the group of officiants. In his left hand he holds a bell, with his right hand he moves a dorje with slow, repeated, elliptical gestures. The low monotonous chanting is carried by the highland wind while the audience stands by, serious and absorbed, but also intrigued and amused by this out-of-the-ordinary day that the village is experiencing.

Back in the temple, the ganapuja resumes and everyone sits back down in their seats. It is time for the offering of food, which represents the experience of the senses. Sweet and salty, sour and spicy flavours are combined in a single bowl: the choice signifies that the different experiences of the senses have a single quality for those who maintain the presence of the state of contemplation.

One of the young monks in charge of distributing the bowls also offers one to four people leaning against the temple door who do not look at all like villagers. They have Tibetan faces but dress Western-style, and their presence is strange in these places where one only arrives on horseback. They are policemen sent from Qamdo, the capital, a couple of days away, to check our permits. Evidently some reports have reached their command. They have rude and arrogant manners, and the eldest one in particular insists strongly that my permit is invalid.

Namkhai Norbu, while maintaining a cold, expressionless gaze, is visibly irate. When he hears them speaking in Mandarin, he asks: “But are you not Tibetans?” The policemen answer yes, then try to justify themselves with an apology: “We thought you didn’t understand the Lhasa dialect”. And he: “In any case, you can guess that I understand the Lhasa dialect better than Chinese”.

The meeting, which takes place while the monks serve sweets and food to the unwanted visitors, ends without any problems for my stay and the puja resumes regularly. I am increasingly impressed by everyone’s kindness, even towards the policemen, representative of a power that is practically invisible here, but which is linked above all to the memory of the senseless violence of the Revolution.

They tell us that in those years, because the Chinese did not have enough ammunition, they used to bring a large number of Tibetan prisoners to the Qamdo area and then make them lie on the ground along the road in two parallel rows with their heads lined up, so that the wheels of the truck could pass over them.

I am always embarrassed to hear these kinds of stories and more than once I have been unconvinced. Like when they told me that the relatives of the prisoners who were shot were asked for money for the bullets used by the firing squad if they wanted to get the body back. It was only after the Tiananmen massacre that I discovered – and with me the whole world – that this custom is still in force today.

They say that Nyaglagar emerged almost unscathed from the events of the 20 years of terror, thanks to the prophetically ‘socialist’ imprint of its founder. Changchub Dorje himself contributed to the village’s activities with his work as a doctor, which had made him famous throughout much of Tibet, and possessed a charisma that did not leave even the enemies of religion indifferent. The accusation of just one of the Tibetans in the area who had gone over to the new regime would have been enough to condemn him to death. But the lama lived a very long time, over 130 years, according to the calculations of his senior disciples. And when the Chinese wanted to put him on trial, no one spoke out against him.

The Dream of Thögal

As I learn more and more about the details of the life of this long-lived, extraordinary man, I want to know everything about him, as well as cultivating the usual secret desire to see him appear before me at any moment.

When we first enter the house where Changchub Dorje had lived, we are followed by a large group of people. His grandson Karwang points out two large wooden boxes inside a dark room. Apparently, the body of the master, preserved in salt, is kept here. Everyone is in silent reflection, while I am a little disappointed. I was expecting wonders, but instead nothing happens.

Raimondo in 1988 in front of Changchub Dorje’s house in Khamdogar, where the master’s body was still preserved in salt.

However, I do not stop hoping that – after seeing me in his room – Changchub Dorje will appear in some dream of mine. Instead, I have a night of fever, cold and diarrhoea. One of the monks who studied medicine with the lama touches my forehead and checks my pulse. Then he returns with a dozen microscopic pills to chew and drink with hot water. I immediately fall asleep and in the morning the fever is gone.

The possibility of a master like Changchub Dorje appearing in a dream is not just my idea stimulated by the stories of his old disciples. Namkhai Norbu himself owes the historical turning points of his life to dreams. The first time was when he saw the master and his village in such detail that he recognized them in the description of a traveller returning from Nyaglagar, convincing him to set out on his journey to come here. The same thing happened many years later, when Rinpoche had by then settled in the West.

He was already teaching Tibetan to students at the University of Naples and was about to marry Rosa, a young Italian girl he had met in Rome. Many students were fond of him and had long insisted that – in addition to the normal university courses – Namkhai Norbu should also pass on the teachings he had received in Tibet.

However, the young lama-professor did not dare take the risk of speaking about the Dharma to people among whom there was not even one who was really interested, and he never felt ready. In his dreams, which also corresponded to deep and natural desires, he often returned to Tibet, the land that politics physically prevented him from seeing again. Not infrequently, his mind travelled to Nyaglagar, one of the last places he visited before leaving the Land of the Snows.

Namkhai Norbu was one of those disciples who could practice even without sitting in meditation. He therefore normally applied tregchöd, a term meaning ‘to cut what binds’. When tensions build up inside, the masters explain, they are like so many sticks that a rope binds together tightly. Cutting the rope loosens the bundle. With years of experience, Namkhal Norbu had managed to fully integrate this practice into his daily life. But the time for the ‘leap’ to more advanced practices seemed still far off.

One night, returning to Nyaglagar in his dream, he met Changchub Dorje. His old master asked him a few questions about life in the West, then asked how his practice of thögal, which means “to surpass that which is above everything”, i.e. beyond the ordinary control of the mind and senses, was progressing. An advanced and one of the most secret teachings, it requires perfect control of one’s body, voice and mind: hence a well-established tregchöd.

Changchub Dorje had already introduced the young tulku to thögal during his physical presence at Nyaglagar. But when he heard that Namkhai Norbu had made no progress in that direction, he told him to go immediately to a famous master, Jigme Lingpa. Namkhai Norbu was quite surprised, for Jigme Lingpa had lived more than two centuries earlier. But, knowing the severity of Changchub Dorje, who did not like to see his advice questioned, his disciple preferred not to contradict him. So he set off without delay towards the indicated place, just above the village of Nyaglagar, climbing up the smooth rocks on which were carved the very verses of the thögal tantra, the new practice he was seeking.

Avoiding the sacred inscriptions, he reached the top and entered a cave as instructed by the master. There, to his surprise, there was only a child with long hair who immediately began to read the text on a small papyrus scroll: the practice of the four lights of thögal. This and other dreams were decisive for the exiled practitioner in Italy. He finally felt certain of what he was doing and confident that he was not teaching his students things unrelated to his own direct experience.

This is what the transmission of knowledge is all about. “If we try to understand what an object in the middle of a dark room looks like,” Namkhai Norbu explains to me, “we can listen to a lot of talk to describe it. They will tell us that it is round or square, high or low, opaque or transparent. But only with direct experience can we really know what it is. The master is the one who turns on the light in the room for an instant and allows us to see for ourselves, like a flash, what that object really is.”

In Search of the Cave

Chatting with the lamas of Nyaglagar, Namkhai Norbu also tells them the story of the dream. Hearing the description of the place, everyone is sure that the cave really exists, and that it is only a few hours away from the village.

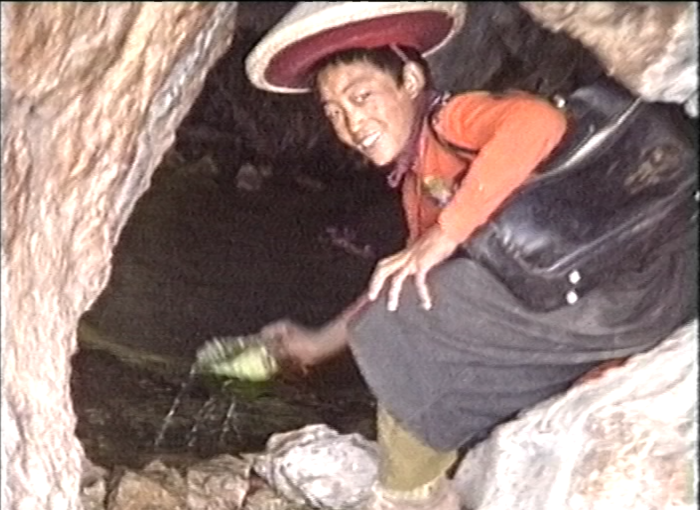

Of course I immediately offer to go, but Rinpoche thinks it is too risky. To reach it one has to use a very long wooden ladder leaning against a rock on an overhang. Tibetan ladders do not have rungs where one can comfortably rest one’s feet, but simple hollows carved into the trunk no wider than 20 or 30 centimetres. Only after two days of insisting am I allowed to search for the famous cave, on foot and accompanied by two boys.

Jedup and Tsema Nongro are good climbers and keep up a brisk pace. I cannot keep up with them, but they often stop to wait for me. For four hours we walk uphill before we reach a large rock summit where not one but two dangerous wooden ladders are leaning. Namkhal Norbu was able to reach this place in a dream, I on the other hand have to climb with my still sickly physical body.

Before I reach the cave, completely exhausted, my two young escorts point out another deep opening in the rock where there is a statuette of Dolma Tara that is believed to be self-originated. Her form is quite well modelled and covered in silk clothes, like a baby doll. I can’t believe it was carved by mother nature, but the rock of the cave is so hard that it seems difficult to shape even with a chisel.

We continue to climb up to our destination, encountering other caves of various sizes, where there are often pools of pure water adorned with large floating water lilies. There is another ‘staircase’ to climb, this one practically suspended in the void, before reaching the top of the cave. The inside of the cave is protected by a wooden wall, because in recent years many yogis have been in retreat here. There is an initial cave from bare rock, then a new wooden door and the meditation room with many unexpected objects: a small table, a few statuettes and ritual instruments.

The interior of the cave transmits a very strong energy that amplifies the sound of the mantras themselves. The two boys light cypress branches with an intense protume, and eagles fly over the valley, illuminated at times by the sun coming in and out of dark clouds that threaten rain. We have to hurry down, but all three of us remain motionless and spellbound, watching the great precipice below us, which continues like a huge wound between the mountains, down to the valley, beyond the Nyaglagar River.

When I get back I describe every detail to Namkhai Norbu, but he does not seem very interested in the cave I visited. He is much more intrigued by a round opening I saw on the side of the nearby mountain, which is practically unreachable unless one turns into an eagle. That could also be the place of the dream, but fortunately he doesn’t ask me if I feel like going back.

My mystical side is now definitely taking over and I am really looking forward to making direct contact with Changchub Dorje. Early in the morning we set off with Namkhai Norbu and the usual group of people for a hike into the heart of the mountain overlooking Nyaglagar. After reaching the cave of teachings, we proceed to a natural vault that gives access to a dense network of tunnels where Changchub Dorje discovered the special clay he used for medicines and sacred objects.

Here Namkhai Norbu prevents me from going any further, with a sharp remark. “It is useless for you to follow me,” he says, “yours is only curiosity anyway.” I feel my pride boiling up again and I am charged with tension. What then is the difference between a sincere desire to know and curiosity? It is no small question. It questions a lot of my past and my convictions.

We have been back for a few hours and it is now evening. I think back to the episode in the cave and admit that, yes, I was first of all curious. But I feel that I really want to understand what the key is that opens the door to the secrets of this place. With this wish, I fall asleep, again to the sound of the long horns which spreads somberly all around.

To be continued

Read Part 1 Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Chengdu

Read Part 2 Background to travels in Tibet

Read Part 3 Derghe and Galenteen

Read Part 4 From Galenteen to Gheug, the master’s birthplace

Read Part 5 On the Road to Nyaglagar

Read Part 6 The Master’s Master

Read Part 7 Waiting for a Miracle

Read Part 8 The Mamo Cave

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988