An Ancient Dunhuang Manuscript by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu

A presentation given on 28 September 2024 in the Merigar Gönpa

When Chögyal Namkhai Norbu first visited London in 1979 he found two important manuscripts on Dzogchen from Dunhuang in the British Museum. A short time later, he started to write a commentary on them. One of these manuscripts was The Little Hidden Harvest, Sbas pa’i rgum chung, a short text by Buddhagupta. Rinpoche wrote a detailed word-by-word commentary on it, citing many quotations from other ancient Dzogchen texts. Rinpoche’s commentary was published in Tibetan by Shang Shung Publications in 1984 and was quite successful among Tibetan readers. It is often quoted by Tibetologists. In addition, in the latest edition of the Nyingma Kama, the collection of written scriptures of the Nyingmapa tradition where we find texts by Indian and Tibetan masters, they have now included this text by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, and this is a very important recognition for his scholarly work. I translated this text many years ago but then it remained as it was so revising it is one of my future projects. It’s a very beautiful book.

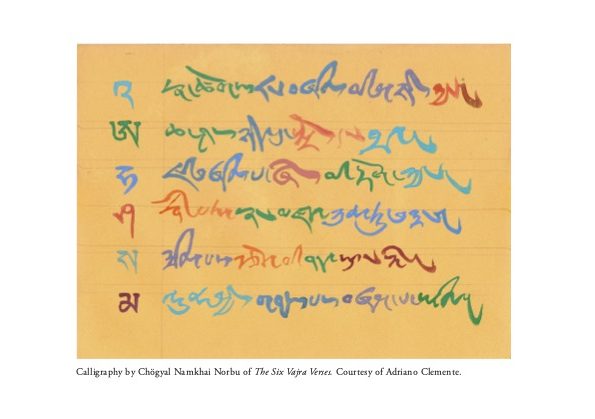

The other manuscript, the Rigpai Khujug, or Six Vajra Verses, has no identified author. Rinpoche started to write a commentary, but it seems he never completed it. He wrote the commentary to the root text at the time, but not the introduction we have now and for that reason it was not published at the same time as the Buddhagupta book. We had to wait many years to have a final manuscript, which he completed about fifteen years ago. However, for several years in the early eighties Rinpoche was always speaking about these Six Vajra Verses. He even embroidered them on pieces of material in different colors, and we hung one of these in the Yantra Yoga studio that we had in Arcidosso.

Why are these Six Vajra Verses called The Cuckoo of Rigpa? The Cuckoo of Rigpa is not the original name but was probably given by Vairocana because they were auspicious for being the first teaching of Dzogchen introduced from Oddiyana into Tibet. In Tibet when we hear the cuckoo, we understand that spring is coming, so in the same way when this teaching arrived in Tibet, knowledge of the primordial state reawakened there.

These Six Vajra Verses in general are called a lung, which is a specific category of texts related to the Dzogchen teaching, especially for the Dzogchen Semde teaching, because all main Vajrayana scriptures are called tantras. When we have a tantra there is a kind of introduction, a setting that explains its origin. Similarly, each sutra explains that at that time Buddha was in a particular place when he gave that teaching and certain students were there and so on. This is related to what we call the Nirmanakaya dimension.

When we have a tantra we usually refer to the Samboghakaya dimension, which is not related to a time or a physical place. But to pay respect to the Sutra tradition, also in the tantras, we read that in this place, like a kind of heaven or pure dimension, there is this manifestation of a Buddha and his students and then there is the manifestation of this tantra. In general when we have a tantra we have that kind of introduction and then questions and answers.

In a lung, we find no such setting or introduction, and there are no questions and answers. Rinpoche explained that a lung consists of the main points of a tantra that have been extracted and collected, which means that it contains the most important points of that tantra. For instance, in the case of Dorje Sempa Namkha Che, the famous Total Space of Vajrasattva, there are about ten tantras including this name, but only one tantra contains the whole lung with questions and answers as well as the setting. In all the others it is scattered, a sentence here and a sentence there.

In any case, the Rigpai Khujug, or Six Vajra Verses, is also contained in the famous Kunjed Gyalpo, The Supreme Source tantra, one chapter of which contains these six verses. The Kunjed Gyalpo is also a tantra, although we don’t know exactly which part is tantra and which part is not because it contains different elements.

The Six Vajra Verses was one of the first five translations made by Vairocana in Oddiyana which he introduced and taught in Tibet and they are therefore always considered highly important for the Dzogchen Semde teaching. In fact at one retreat that Rinpoche gave at Christmas in 1985, he taught and explained just these Six Verses for the whole retreat.

This commentary that we have in the Dunhuang manuscript clearly explains what the difference is between the Dzogchen teaching and Mahayoga or general Vajrayana teaching. It was written for practitioners of Mahayoga because it uses that kind of terminology. Tradition has it that when Padmasambhava arrived in Tibet, he mostly taught Mahayoga and not Dzogchen, and in some cases, when he taught Dzogchen, he used the terminology of Mahayoga. This is why when we study in the famous Garland of Views in the Santi Maha Sangha base we may wonder how this can be Dzogchen when it doesn’t even mention the primordial state and essence, nature, and energy and other terminology that we find in Dzogchen in general. But if we understand correctly, we will recognize that there are many explanations about Dzogchen because it is related to the famous Guhyagarbha tantra, which has also been commented on according to the Dzogchen principle. But of course Padmasambhava also gave many Dzogchen teachings that were rediscovered as termas, and so on.

The Six Vajra Verses is one of those texts that Vairocana brought back from Oddiyana together with other original texts at the time of King Trisong Detsen. Vairocana introduced these original scriptures into Tibet and then Vimalamitra continued this work and brought many Dzogchen teachings there. So we have these three series: Semde and Longde, mainly related to this Vairocana transmission, and Upadesa, related more to Vimalamitra in the Kama tradition and Padmasambhava in the terma tradition.

Why are these Six Verses so important? Because they explain the principle of the view, meditation, and result in Dzogchen. First of all, they introduce the view: sna tshogs rang bzhin myi gnyis, cha shas nyid du. Sna tshogs rang bzhin means that the nature or variety or multiplicity is nondual. In general, many teachings give this explanation. When we say that the “base,” the condition of the phenomena of existence, is nondual, it means it is impossible to distinguish between one phenomena and another in their essence. This is not only in the Dzogchen teachings, but also in Hindu traditions such as the Vedanta and so on. They explain the same principle such as maya, or illusion: there are no realities as they are all one nature and their real nature is this principle of the absolute.

Cha shas means single part and nyid du means in the state or in the real condition of that single part. In spros dang bral, spros pa means that we have created some concepts, constructed something with our mind. Concepts constructed with our mind also refers to the concept of real nature, the concept of the absolute, which is also this spros pa, because it is a result of some reasoning. Cha shas nyid du means that nature, which is nondual, must be recognized or experienced in the state of the individual. It is not some kind of abstract or absolute, but it is the real nature of each individual. Then through that individuality, we can discover our real nature or nondual nature. This is the view and is an introduction, in general, to the Dzogchen teaching because the view in Dzogchen is not an intellectual view, but is based on experience.

The second two verses explain meditation or how we apply that recognition or knowledge that we had. The text says ji bzhin ba myi rtog, which means that even if we don’t have any concept about that nature – because ji bzhin ba means “as it is”, something we cannot modify with our concepts, with our ideas – while myi rtog means we are not thinking about and judging that. If we are doing meditation we do not keep that concept. For instance, Dzogchen practitioners have received what we call direct introduction to the state of Dzogchen. How do they apply that? Through meditation. How do they do that? They do not think about being in their real nature, in their primordial state. They do not think, “Oh, now I am in the primordial state, now I am not” because that would be judging something as if it is an object of the mind.

What, then, should we do? The text explains: rnam par snang mdzad kun tu bzang. Rnam par snang mdzad means whatever form we perceive with our senses. Rnam is form, snang means to appear and mdzad means to make this manifestation appear. So whatever we perceive, kun tu bzang means everything is fine. It means that when we are doing Dzogchen meditation we do not judge but our senses are open to all perceptions and we remain in that clarity.

Regarding the fruit or the result, how can we achieve it? In the Sutra tradition, we have five paths and ten levels of realization. Through each path or level we gradually remove or abandon some obstacles, emotions, and concepts until finally we have purified everything and we are finally a Buddha. In the Vajrayana, first we have the Kyerim stage in which we create a mandala and then integrate that mandala with our energy. In the end we transcend all concepts in the state of nonduality. This is also a gradual way of progressing.

In the Six Vajra verses it says zin pas stsol ba’i nad. Zin pas means finished, completed, or accomplished. It means whatever idea we have going from one place to another, from Samsara to Nirvana, or from impurity to pure dimension, we are already in that Nirvana, or in that pure dimension. We have the capacity to be in that state – like the title Cuckoo of Rigpa – that by abiding in that state, the rays of the sun naturally eliminate all the clouds. We don’t need anything external to ourselves to remove the clouds, such as methods in sutras or tantras. The Dzogchen method is the sun shining by itself, and that is the way. If we have that capacity, then we can say zin pas, everything is already accomplished, already completed and in that case, stsol ba’i nad, the illness of effort is abandoned. We always have the idea that we should put some effort if we wish to progress, to purify because that is related to our condition. If we need to put in a lot of effort it means we are still not on the real Dzogchen Atiyoga path, however, we are preparing to reach it, which is good, of course, because one day we will reach that level, that stage.

Then the last line is lhun gyis gnas bzhag pa. Lhun gyis in general means spontaneously or naturally, but Rinpoche interpreted this to mean lhun gyis grub pa which means already present or, as we say in the Dzogchen Community, self-perfected. In general, in the Dzogchen teaching, we have these two aspects, kadag and lhundrub. Kadag is this nondual nature while lhundrub means the primordial state or nondual nature that already contains all these self-perfected qualities that only need to be manifested. Sometimes lhundrub is compared to the oil from sesame seeds. If the seeds are not pressed we do not have the oil even though the oil is there. In any case, here it says that remaining in that self-perfected condition is the state of contemplation, the final result. We don’t need anything else.

This is a very concise explanation of these Six Verses. This book is a beautiful commentary, both the original and what Rinpoche wrote. It’s very important and explains how Atiyoga should be. The Six Verses are explained very clearly, as well as how we should practice and how we should achieve the final result.

https://www.shangshungpublications.com/en/explore/new/product/e-book-the-cuckoo-of-rigpa-epub-mobi

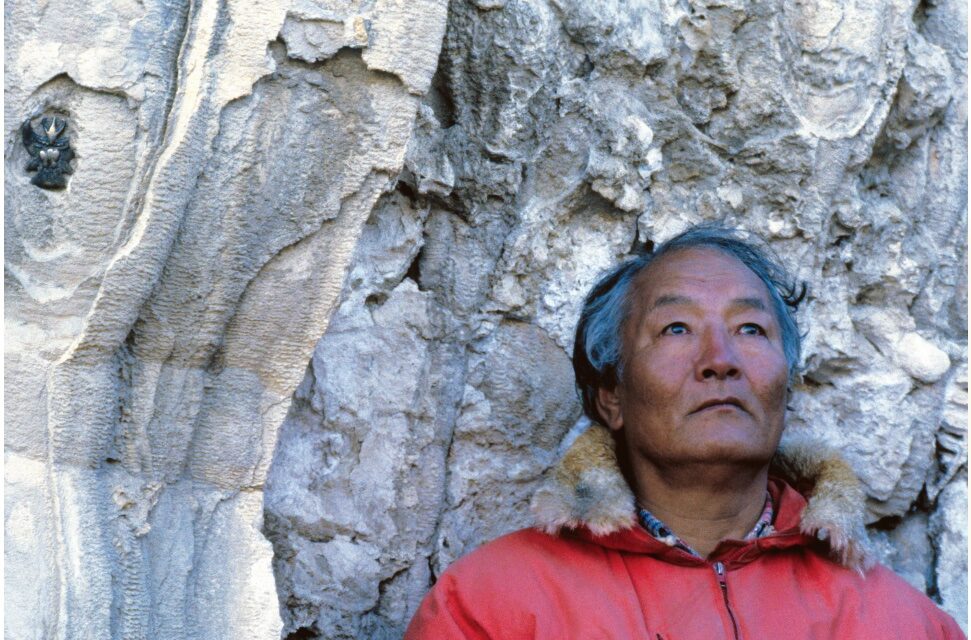

Featured image: Chögyal Namkhai Norbu at Khyung lung dngul mkhar with an ancient silver amulet of a khyung (Garuda) he discovered (in rock face upper left). Courtesy of Alex Siedlecki.