Living Music

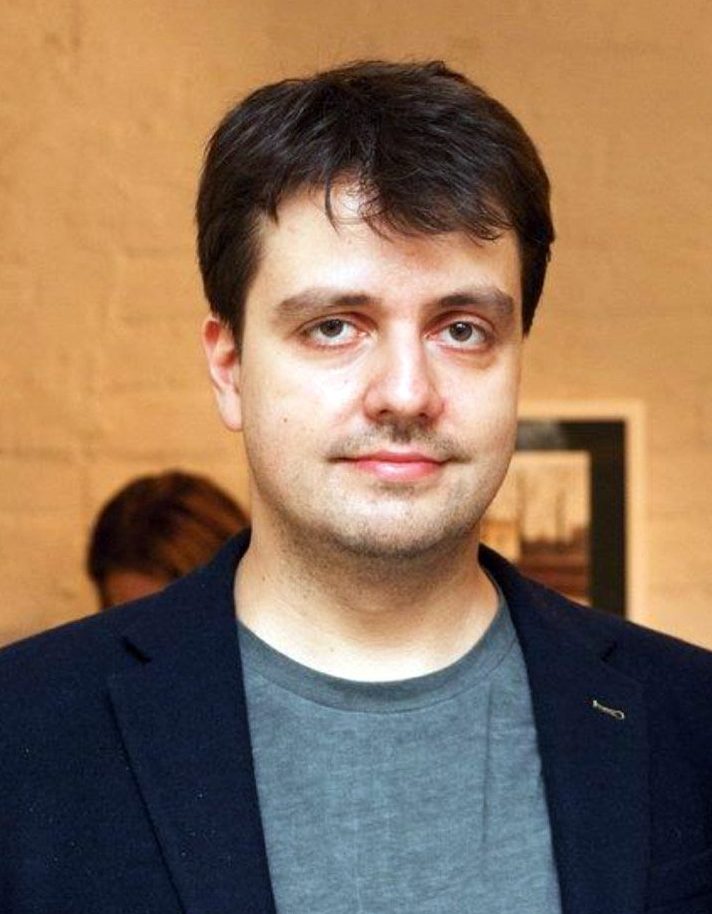

Oleg Troyanovsky, composer

The Mirror: Could you tell us about your childhood and background.

Oleg Troyanovsky: I was born in Geneva, Switzerland, and lived there the first years of my life because my parents worked there. My father served as demographist at the UN. I went to kindergarten there and then to school. When I was 13 years old, my parents moved from one flat to another, and in the new apartment there was a piano. That’s how I accidentally met music for the first time and I liked playing music and composing very much. I had an idea to become precisely a composer and asked my parents to find me a tutor, and eventually enrolled at a music school.

Later my family returned to Moscow, Russia, and I was very curious to find myself there because of its rich musical life, the Conservatory, and the history of the Russian composers. In Switzerland there is not such a great history of music like we have here. Gradually I started to prepare myself to enter the Moscow Conservatory and graduated from it as a composer at the age of 24.

M: How did your studies go at the Conservatory?

OT: I have always been composing because it fascinated me. Then I needed to do it in my course of studies and of course I did it for pleasure. I started with the modern Russian and Soviet composers but with time my preferences changed as I began to learn more about music at the Conservatory. I cannot say that there was the most progressive approach to composition there but it gave me profound knowledge of traditions, classical and 20th century music. As for the rest, I had to learn by myself and search for practicing composers and try to train with them.

M: Were you influenced by any particular composers or musical genre?

OT: When I started to study I was keen on the music from the end of 70s and 80s. I was not interested in Shostakovich and Prokofiev much as they already belonged to the past. I began with Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, as well as John Cage, György Ligeti, and Iannis Xenakis. Then I started to move forward as this music was already becoming classic. I became interested in electronic and modern orchestral music, as well as Moscow conceptualism in a wider sense. Today I compose and produce music for my albums, art installations, music for cinema, video games, animations, musicals, etc. Today orchestral music continues to live mostly in the sphere of cinema and video games.

M: How did you meet Chögyal Namkhai Norbu?

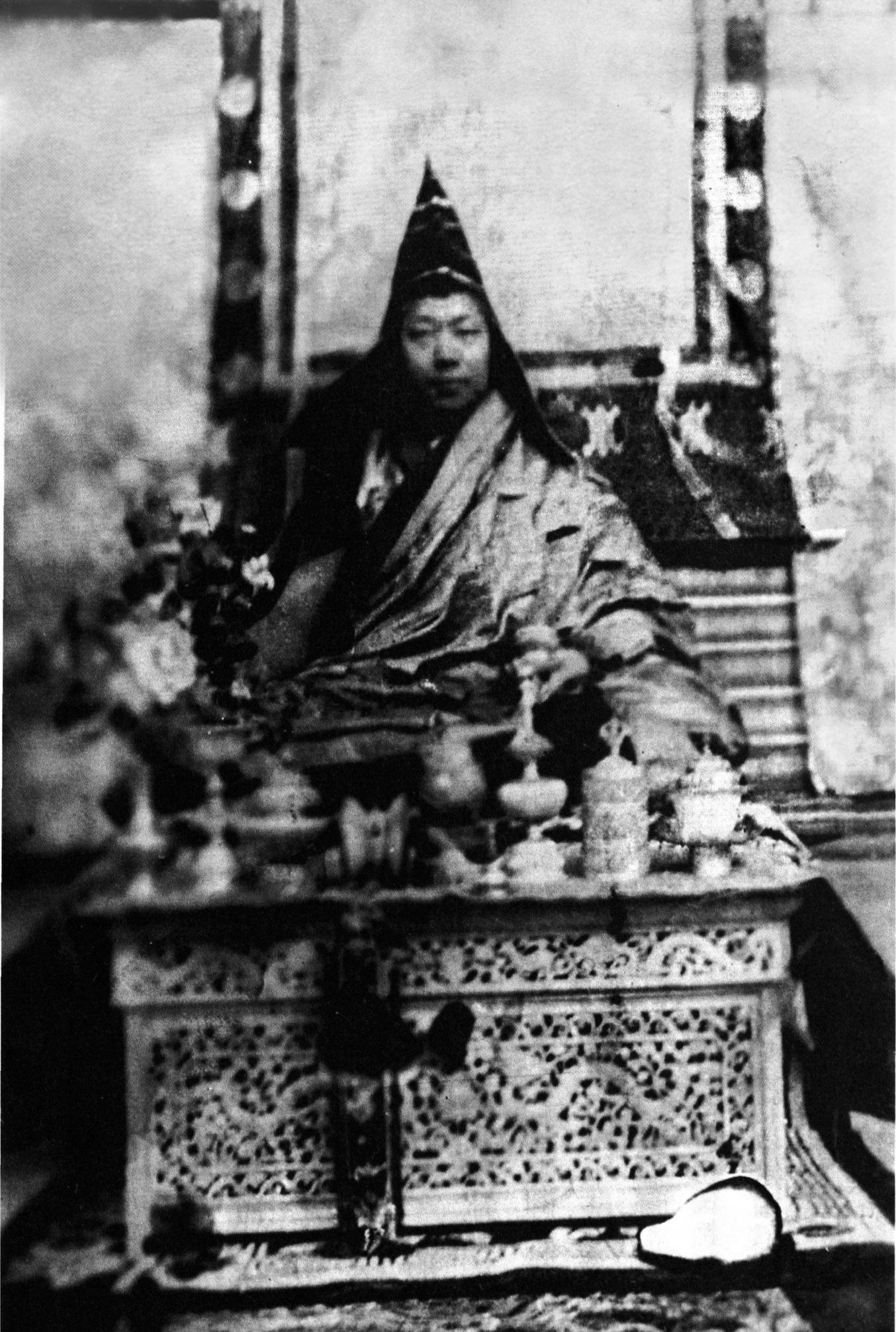

In 2002, when I was 22 years old, my friends and I happened to attend a Buddhist lecture in Moscow. It left me curious. At that time students had a longer vacation so I decided to spend half of the summer in Buryatia to get to know more about Buddhism, as I knew that in Russia it is present mainly in Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva. At that moment a great Tibetan lama, Bogdo Gegen, came to Buryatia to visit and I participated in his seminars, where he taught a lot of Buddhist philosophy and practice and gave commentaries. Among his students there were some people who already knew Namkhai Norbu. They told me about him and gave me his book The Mirror: advice on presence and awareness. I remember reading it although it did not impress me much, but I remembered the name – Namkhai Norbu.

Half a year passed and I continued to study Buddhism. In particular, I came across the Dalai Lama’s book on Dzogchen. Then one of my acquaintances recommended another of Namkhai Norbu’s works and at that time it impressed me a lot and I lit up with interest. I suppose that in my case without preliminary preparation more advanced topics did not have an effect. But when I already had some minimal idea about Buddhism in general then Dzogchen seemed much more interesting and timely. Especially precious was that Rinpoche, being a University professor, understood very well how to teach meditation to westerners beyond Tibetan cultural and religious conventionalities.

Six months later Namkhai Norbu came to Russia. And it was surprising that Kunsangar – the place where he gave the seminar – was a twenty minute walk from my parents’ summer house. My father had bought a house in Pavlovsky Posad, and Kunsangar was located right opposite the river. It was very convenient. I met Namkhai Norbu when he conducted a Santi Maha Sangha training. I did not participate, but at some point I came up to him to introduce myself. Later there was a lecture in Moscow and my trip to Merigar, Italy, where I had a chance to get to know Rinpoche more closely. I mainly asked him stupid questions on Buddhist philosophy, and he, answering me, tried to give me some practical understanding, for which I am very grateful to him now.

Later, in 2010 I became a Santi Maha Sangha instructor. At that period I coordinated practices in Moscow and often attended them. People would say that there was no instructor in Moscow and would ask me if I wanted to prepare for the exam. At some point I decided to do it. I cannot say that I enjoy it when I teach and there are people in front of me listening. My motivation was quite straightforward: I just wanted to get to know Rinpoche more closely and have the possibility to communicate with him.

Now I understand that it’s quite a naive idea, because it does not really contribute to successful mastering of meditation. It’s not necessary to know the teacher well, ask many questions and be in touch with him. But as a result I understood that, thanks to my being an instructor, I think I have learned Santi Maha Sangha material really well. My understanding of Dzogchen practice became 10 times better than it was before, although it’s still not precise enough.

M: Did your meeting with Rinpoche and the teaching influence your creative work?

OT: In 2004 I flew to Margarita Island in Venezuela, where Rinpoche had been spending a lot of time, so I spent a lot of time there, too. As Rinpoche was also a musician, he used to constantly play music and sing. Rinpoche exuded Tibetan music, he talked about it and sang, so these absolutely peculiar Tibetan melodies based on a pentatonic scale assimilated in me and I feel their presence in my musical style. On another level, general ideas related to Buddhism and Dzogchen somehow also assimilated in me and began to manifest in my music. Of course, the practice of presence and awareness helps me to focus on my work and to work more effectively.

Not long ago I produced a musical album called Protomusic, which I made as a creative experiment. It is available on Spotify, Apple Music, Itunes, etc. I tried to imagine a general, even primitive sound base which could serve as a prototype for more complicated musical pieces, and which listeners can think up themselves in their imagination. Probably this idea was inspired by a Buddhist concept of the existence of mind and nature of mind or relative and absolute truths.

Another project I am working on now is a musical album for a mobile app called Andante: living music. It’s a new type of classical music that is improvised the moment a person launches the app. As a composer I have made special musical themes and an algorithm, artificial intelligence, creates new, unique improvisations each time.

These creations are personified and correspond to the time of the day, your mood, your occupation – whether you are working, resting or going to bed. I think this idea of instant spontaneous manifestation of music was also inspired by Buddhist principles, although I did not intend to do it.

M: How do you compose music and which tools do you use?

People often have a magical idea of how music is created. Music is remotely reminiscent of language. We pronounce words, express ourselves, we can speak quietly, loudly, softly, sharply. The same applies to music. When some language becomes native to you, when you’ve learned it very well, it’s easy to compose a poem or begin to write a text, an article, a story on a specific topic, and in the same way you can sit and compose music.

I mainly play keyboard instruments, then there are others that I use in special cases – percussion, violin, guitar, hand-made instruments for creating ingenious original sounds. But in general I create music on a computer, even orchestral music. In the 19th century the composer’s job consisted of writing a musical score, a text of notes, which later musicians would perform on a stage. Nowadays they do not expect a musical score from a composer but a completed musical recording, with or without orchestra. That’s why a modern composer’s job includes composing music, writing a musical score, and recording and preparing a completed audio-file.

Today the whole work is totally performed on a computer which gives a composer a wider range of opportunities: on software synthesizers one can create an infinite quantity of tones, sounds, etc. In general I use Logic Pro X software and many additional apps. If I need to record live instruments, live orchestra, I prepare a special musical score, then record and at the end process it on the computer and create an electronic file, be it music for a movie, video game, installation, museum, or modern art gallery where music is a part of exhibition.

M: What other projects do you participate in and who have you been working with?

In 2015 they asked me to write a radio symphony, a kind of musical play in a free manner for Russian radio (https://soundcloud.com/olegelo/radiosymph). I decided to give a new meaning to the old genre – a symphony where actors read texts between musical performances. I made a hybrid of a symphony and a radio program: at the beginning listeners perceive it as a radio program about five totally different composers who seemingly participate in a music festival. They show their ‘own’ distinct music pieces and at some point even argue. But then it becomes obvious that these are all fictional heroes and in reality it is a musical composition in five parts. I wrote all the music and the composers were played by actors. I called this piece Radio Symphony. Later it was selected for a prestigious Berlin festival Prix Europa in the nomination Musical Radio Project of the Year and I received a special prize, taking 2nd place.

Very recently, during the pandemic, I took part in a composer’s competition organized by the HBO company that produces the famous series Westworld. It was called Westworld Scoring Competition. They wanted a musical composition to a five minute scene from the series. It was April, everybody was still in lockdown, I had nothing to do and decided to work on that. I did partly electronic, partly symphonic orchestral music entirely on the computer (https://youtu.be/AVrv6o1M82Y). To my surprise 11,000 composers around the world participated in this competition. Finally six winners were chosen, including me. In fact it was the biggest composer’s competition of recent years.

M: Do you have any plans for the future?

OT: I would like to continue the work I started with the app Andante: living music – to create a musical album, not in the old format where all music is recorded and does not change, but to create a musical album in the form of a mobile app, as it gives more opportunities for interaction and creation of a more alive music which can change each time it comes into relationship with listeners, sounding differently depending on circumstances, time of day, routine, and so on. In general I think that there is much that is new and unknown in music that can manifest, in particular thanks to new technologies.

M: Thank you for the interview, Oleg!

Oleg Troyanovsky