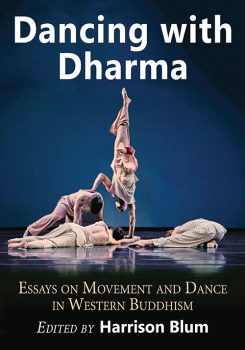

Essays on Movement and Dance in Western Buddhism

Essays on Movement and Dance in Western Buddhism

Ed. Harrison Blum

McFarland and Company, inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

2016

272pp

ISBN (print) 978-0-7864-9809-3

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4766-2350-4

Dancing with Dharma is the first proper survey of dance practice in western Buddhist circles: a trailblazing collection of 38 essays from 27, mainly North American, contributors. It is also an expression of a more general recognition of the importance of paying attention to the body. Some of the essays here are not actually about dance at all: Reginald Ray, for instance, presents a practice he has devised called “earth breathing” as a means of deepening embodied consciousness, arguing that meditation be approached not as “left-brain, top-down”, but rather as “somatic, bottom-up”. Dance is, of course, the most expressive and potentially joyful way of engaging with the physical. Gone are the days when the only alternative to hours of sitting on the cushion was desultory sessions of somber walking meditation.

Most of the dance practices described here share the following two characteristics: they are improvisatory and self-consciously therapeutic. Practitioners find their own way, individually or in a group, towards moving in a specific fashion, meanwhile reflecting on what that experience reveals or resolves. As one teacher says: “By looking inward toward our stress and understanding ourselves through our dancing bodies, we invite the possibility of quite literally moving beyond what binds us.” Much of this is not intrinsically Buddhist. A number of the contributors originally hail from what might be described as New Age dance groups (such as 5Rhythms or Continuum Movement) or belong to the secular American Dance Therapy Association, which now even brings dance therapy into public mental health institutions.

What makes these practices Buddhist is essentially that they are all seen as means of cultivating the central Buddhist virtue of awareness, generally rooted in a schema of Buddhist categories, such as the four foundations of mindfulness, the five (or six) Buddha families of the tantric mandala, or the three phases of the trikaya doctrine.One contributor also identifies “flow” or “breakthrough” states with moments of Buddhist insight. The so-called Dharma Jam developed by the book’s editor Harrison Blum, though perhaps a little noisier-, or poppier-sounding than others, is a case in point. Participants dance in their own style to contemporary tunes of building tempo, interspersed with moments of stillness and enquiry, bookended with short periods of meditation. Three phases called Tune In, Get Down and Join Up are linked to the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. “The Buddhist part of the dance happens internally,” Blum explains, “in how we perceive and respond to experience.”

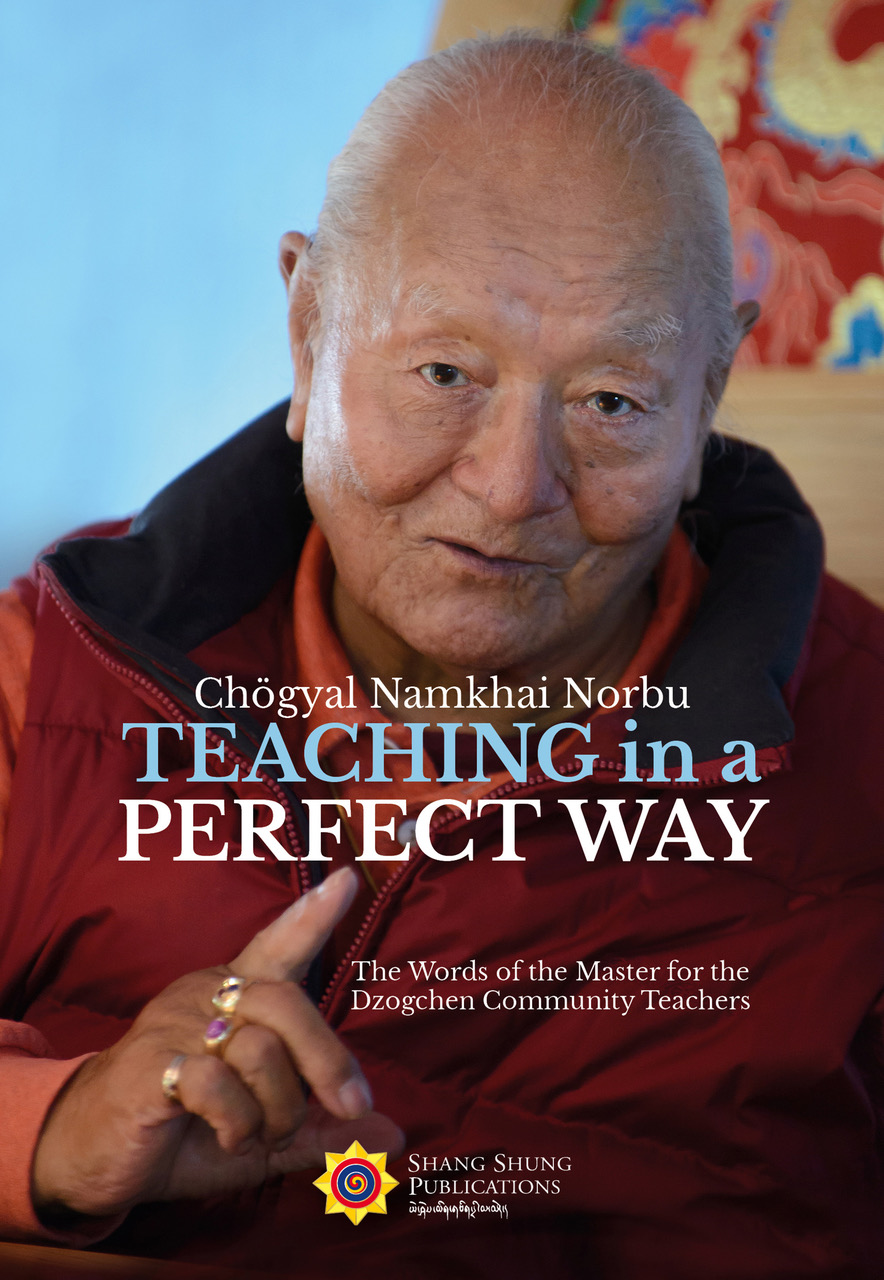

For those of us in the Dzogchen Community used to the highly formalized practices of Vajra Dance and Khaita, both of which demand hours of concentrated application simply to master the basic steps, such comparatively free approaches seem lacking in a sense of discipline, or of subjecting oneself to a path of training. As a Theravada Buddhist nun, writing here on body awareness and qigong, puts it sternly: “While certain forms of spiritual dance can be very reflective, a lot of dancing is not about waking up. It’s about following impulses and desires.” Formal, choreographed dance practice, conversely, provides a vessel within which impulses and desires are checked and transformed. It is also less self-consciously therapeutic, as the benefits of the practice come more directly from the performance itself, and less from subsequent reflection or interrogation of the experience.

Interestingly though, the spiritual value of undirected, impromptu dance is endorsed, here, by the Tibetan yogic tradition. The esteemed Karma Kagyu yogi and scholar Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso Rinpoche would often ask his students to dance spontaneously, whether they were in a secluded mountain retreat, or in a busy street or airport. From the enlightened perspective, all movement can be experienced as the dance and play of pure, Buddha energy. “Every time your body moves around, it is vajra dance,” Khenpo Tsultrim avers. He continues: “The buddhas surely do sing and dance,/ To sing and dance is surely profound practice,/ By practicing profound song and dance,/ We reach enlightenment – how amazing!”

Of the practices described here which are formally choreographed, two derive from Vajrayana Buddhism. The first is an ancient tradition called Charya Nritya, originally the preserve of Nepalese priests, recently brought to a Newar Buddhist temple in Portland, Oregon. The second is a dance of the 21 Praises of Tara, created in Hawaii during the mid-1980s via the visionary collaboration of a western woman called Prema Dasara and a Tibetan teacher called Lama Sonam Tenzin. Both employ costume, music, mantras and mudras to express the qualities of the tantric deity. The Tara dance is a group practice celebrating the divine feminine, which has travelled around the world and been performed before many Tibetan lamas.

The third, the Dances of Universal Peace, came into being in the late 1960s when a Sufi teacher in San Francisco saw the need for people to experience “joy without drugs”. The dances are ecumenical in spirit, each having as its seed a sacred phrase from a particular religion, and are “a communal expression of our need to come together and say ‘no’ to destruction and ‘yes’ to life.” Watching these dances, the head of the FPMT organisation Lama Thubten Zopa said: “I have been sitting here making prayers that you never stop doing what you are doing. The airwaves of our world are polluted and these songs and dances help to purify them. You have no idea of the power of this practice so please keep doing what you are doing.”

Review by Alexander Studholme