Babeth M. VanLoo – Filmmaker & Artist

My name is Babeth Mondini-VanLoo. I was born in Holland and as a young girl I moved to Germany to study art a.o. with the artist Joseph Beuys. He taught us that motivation is of primary importance when creating art. Some of his works he called Invisible Sculpture because it was a container for all kinds of art and part of his larger notion of the Social Sculpture, meaning that art could heal society.

He also initiated ecological art– he planted 7000 oak trees as art – or he cleaned a river, and he co-founded the Green party. He also coined this phrase “Everybody is an artist”, broadening the notion of art, and that art can be active at all levels of society.

When he was fired by the government for occupying the academy together with us students in 1972, in protest of denial of free choice of study during this period of political turmoil (Notstandgesetze), I wanted to leave Germany.

I received a scholarship to study film in New York and in 1976 I got in touch with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche there. In Germany I had already met the Maharishi so I had done a bit of transcendental yoga meditation, however, there wasn’t that heart connection with the Maharishi as a teacher. But when I met Dilgo Khyentse it right away felt like coming home. Something changed within me and I felt that I needed to study this.

I got my Masters in Film & Arts when I moved to San Francisco and around 1977-78 met Dudjom Rinpoche. There were many Rinpoches there so this connection was nurtured in California. When I moved back to Holland, I met Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche in 1982 and I would call myself a practitioner from that time on, because that was when I started to have a daily practice and to not see Buddhism as an inspiration for my life, but as a basis because of studying with him.

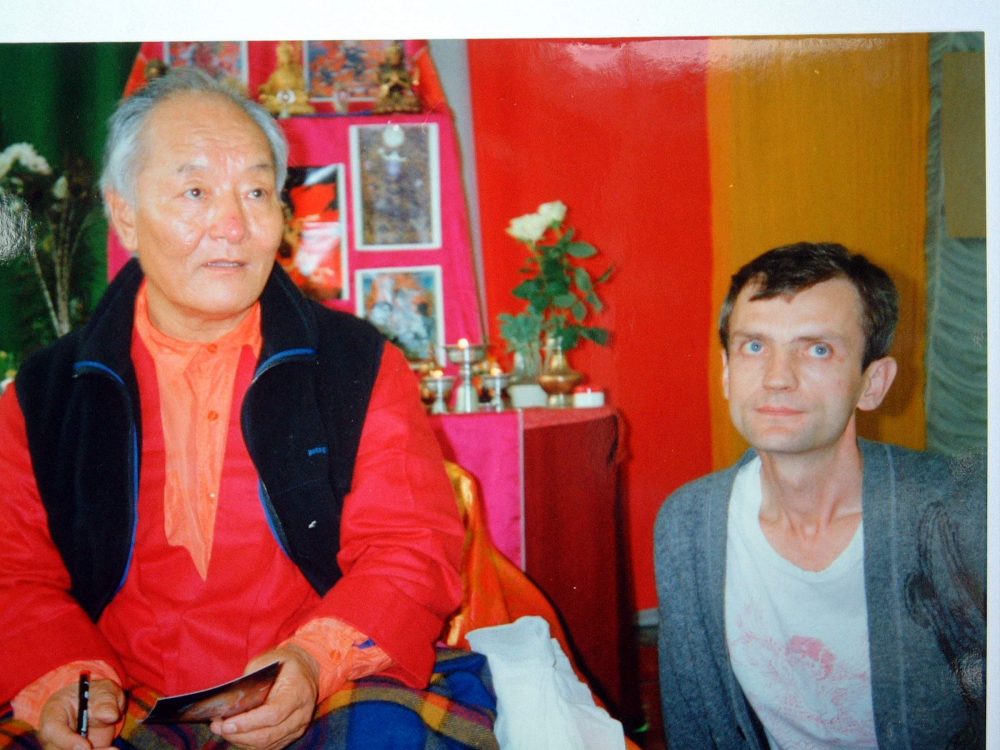

Babeth & Kazuaki Tanahashi, a Japanese Zen master, artist, calligrapher and renowned scholar, during the film she directed and produced in 2013 called Painting Peace.

Afterwards I understood what an amazing blessing it was for me as an artist to get in touch with Dzogchen and Vajrayana teachings, because they provide an artist with the broadest space. It’s the Path of Self Liberation and that really fits very well with the practice of art. It is not that I decided to become a Vajrayana practitioner but somehow our destiny brings us to the practices that connect best to our own nature.

Then after many art and music films in 1989 I made my first Buddhist film on 16mm, during the cremation rituals of Dudjom Rinpoche in Kathmandu. I worked together with John Halpern who I had met thru Joseph Beuys and we received permission from Shenpen Dawa, Dudjom Rinpoche’s son, to make the first 16mm film in their monastery in Kathmandu, where Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche was presiding over the cremation rituals. I remember distinctly that when I went to get a blessing from him I was carrying my Bolex film camera and as he took his stick to bless me instead of blessing me on the head, he blessed the camera. When I kept on waiting to get a blessing on my head he started laughing. I will always remember that moment as a sort of empowerment to use filmmaking or video as skillful means to put the activity of the wisdom mind into forms of art.

Before 1989 I had created art installations with light and film. These were presented in public spaces, like museums or galleries. I was also doing these light sculptures with Buddhist content, so some are like modern prayer wheels. For example, in the fall of 1991 I was invited to present my artworks during the Year of Tibet with HH the Dalai Lama in New York, in a gallery. I had made three lightsculptures with film, one on Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one on the cremation rituals of Dudjom Rinpoche, and another was a prayer wheel with His Holiness. Imagine: the outside is plexiglass and copper in which I enclosed 35mm film images that I had filmed with the Dalai Lama, and inside neon lights and a mantra by His Holiness. When you turned the wheel, not only the mantra by His Holiness became active, but the film images looked as if he was giving you a blessing.

And then an amazing thing happened when Richard Gere opened that event. I had made an invitation card with Dilgo Khyentse’s image on it and people had to bring it to get into the gallery. However, right before the night of the opening he passed away. In the morning I heard that he had died and I put a truckload of earth in the gallery with a neon halo on it, and some incense as part of the installation. When Richard Gere, who was also his student, came in, we really transformed the space into a shrine ritual to commemorate Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. Sometimes that kind of synchronicity happens in Buddhism.

My connection to Dilgo Khyentse as a student also helped to receive permission to start making movies in Bhutan, at that time still a very restricted area. My first three one hour movies in Bhutan were about the women, working with a great Bhutanese collaborator, Karma Pem. At that time changes were taking place there with the first introduction of television and urbanization. The first film documented the women in the rural areas where there was a matrilineal system in which the land passes from mother to daughter, and women had a very equal relationship to men. It was fantastic to see this in Asia.

The second film was on urbanization.

![Khandro_Poster_print[1][2]](https://melong.online/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Khandro_Poster_print12-252x350.jpg) The third film was about the daughter of Dilgo Khyentse, called Chime Wangmo and about his wife, Khandro Rinpoche, who was an incredible doctor and healer. She had been instrumental in starting up a Buddhist nunnery called Sissinang. There were many blessings from giving these women a voice in these movies.

The third film was about the daughter of Dilgo Khyentse, called Chime Wangmo and about his wife, Khandro Rinpoche, who was an incredible doctor and healer. She had been instrumental in starting up a Buddhist nunnery called Sissinang. There were many blessings from giving these women a voice in these movies.

Of course there had to be a good film on Namkhai Norbu. I had lived in Tribeca in New York at the beginning of the 90s and my neighbor one block down was Jennifer Fox. Our paths would always cross. I had made a well-known documentary in Haiti in 1991, a very political film, against the military coup. At that time Jennifer had made a film in Lebanon and both our engaged movies travelled the American circuit. I also would go to Jennifer’s house to do practice. We both had Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche as a teacher, so she was a dharma sister, a friend and a colleague. That was so rare!

Later on when I became the head of the Buddhist television station, I knew that Jennifer would be the best filmmaker for that film because over all these years I had seen her collecting material about Namkhai Norbu, plus she is a great documentary filmmaker. It took me almost 5 to 7 years to convince her to do it, because there was some hesitation on her part. Also because I initially wanted the film to be about how it had changed her life, how Buddhism influenced her filmmaking, changed her view as an artist, but she didn’t want to do that. Then she came up with the idea of making the father-son relationship as the main focus of the movie. I am so glad to have initiated that film and to have been her co-producer and commissioning editor for My Reincarnation because one of the major benefits of doing it was that in the process all of her material was catalogued. I felt that that was a big blessing, to have 25 years of audio visual material catalogued, and donating that to Rinpoche.

So in the year 2000 I became the programming director of the first Buddhist television station in the western world, in Holland. The first time we broadcasted I had a flashback of Dilgo Khyentse blessing my camera. It took 7 years to get the permission and finances from the government to start as a PBS- Public Broadcasting Station. I felt that it was important for Buddhism to enter into people’s homes who did not already have a connection, so not preaching to the converted, but to inspire through the medium of television.

Only one third of our programming was religiously oriented. The rest was Buddhism as a way of life, a philosophy, as an empowerment for people to lead their lives. Holland is a Christian country but people had a problematic relationship with the institution of the church. Particularly young people, who dismissed religion still had questions about life ‘s mission, what can guide us, how can we lead our lives, ethics. We did not try to convert anybody. We offered guidance in ethics. We had started this within the Buddhist Union of the Netherlands so we were all inspired by those means that Buddhism offered us – non-violence, the view on interdependence.

HH Dalai Lama, Babeth & Laetitia Schoofs. The photo was taken while Babeth was directing the film called Dalai Lama: Well-being, Wisdom & Compassion, in 2014.

I remember that the first program that I put on was the Dalai Lama teaching the Four Noble Truths. After that a lot of cultural programs. For example, about Philip Glass as a music composer. He had been a long time Buddhist practitioner but the word Buddhism only appeared once or twice in the film. He spoke beautifully about how meditation would influence his playing and compositions. We showed a similar film on John Cage. I had taught film making in academies for 24 years and while teaching at the Royal Conservatory of the Hague, a music conservatory where I taught Phaenomenology of Image and Sound, I had the opportunity to invite John Cage to come and teach with us. John had similar experiences. The way that he introduced silence into his compositions was definitely linked to his practice of Buddhism. So our programs were not merely on Buddhism itself, but on how it guides our lives.

And talking about interconnectedness, this was a time that Buddhism in the west was branching out. At the beginning we could only show documentaries but later on I got a permit to also co-produce fiction films.

Then we also zoomed in on what was going on in Buddhism in relation to science and medicine. In 2001 when I made programs with people such as Jon Kabat-Zinn, one of the first people to introduce mindfulness to terminal cancer patients in the United States, nobody had even heard of him. Now those type of mindfulness treatments are all over. Or people like Goenka who had trained many of the early American Buddhists, or those who introduced the use of mindfulness meditation in jails, and also the people who started the Insight Meditation center in the US. This was a time when the kind of wisdom contained within the Buddhist community suddenly started to go out to the wider world.

Only a small percentage of our viewers watching our ‘slow tv’ were Buddhists. There were deeper discussions and documentaries integrating the experience of seeing Buddhism. In other words, feeling what comes across. For us as filmmakers this is one of the big challenges: how to introduce that level of feeling not just on a cognitive level, and make an audience experience. People may have been poisoned by commercialized television where they are consumers rather than participants. Buddhist television really used this element of making viewers participate, waking people up to think for themselves.

Unfortunately, January 1, 2016 marked the moment when the Buddhist television station, as an autonomous Public Broadcasting Station, was closed down. It will no longer be a separate station but there will be some slots allocated to Buddhist films under the umbrella of a Christian station, where my successor will have less airtime, more rules, bureaucracy etc.

The budget for television was cut drastically, and all the religious stations were dismantled, not only the Buddhist station, and so this marks a point in history of a very different kind of political and cultural climate in the Netherlands.

Now I think one of the main things is how to guide the archive of all these films that have been produced over the last 15 years. One important thing to add is that because I went on a lot of the shootings as a producer, I always made sure that when there were any kinds of rituals involved that we documented the whole ritual. A normal TV crew would just film a small part because they knew that they would only use a few minutes. But for me as a Buddhist practitioner and filmmaker in charge, I knew that it is important to safeguard that whole ritual for future generations, and especially in the Tibetan case because many of the Rinpoches of that generation were still born in Tibet, and not in exile, and have already passed away.

I really hope with the little capacities that I still might have to contribute to that because I feel that such archives should be disclosed to future generations, to Buddhist scholars, or people who might want to study Buddhist media, as now many Rinpoches also teach online. This is something new that has come about in the last 20 years. The teachings were always restricted to receiving them orally. And now they are available online. This is a whole new trend that needs guidance, of teachings being given as a service to the world.

I really feel that there is a strong connection between making art and Buddhism. Both require that inner introspection, and contemplation to unleash our full creative potential as human beings.

A Buddhist television station was for me what my art teacher called a Social Sculpture, an artwork that touches people and can have an influence and benefit society. It may plant some seeds. I believe that our Rinpoches are working like that as a service to the community, and I feel blessed that I can be of service in an artistic way as part of that transmission through modern media and creativity.

Babeth M. VanLoo

Director/producer FILM ART Amsterdam

Director BFFE @EYE Filmmuseum