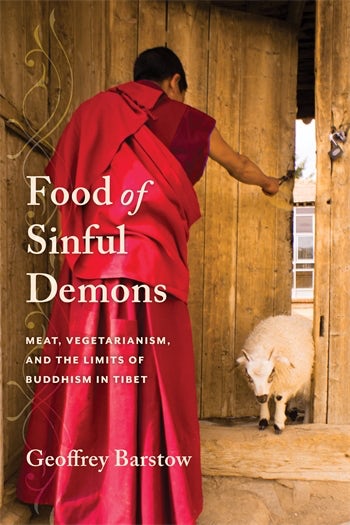

Meat, Vegetarianism, and the Limits of Buddhism in Tibet

by Geoffrey Barstow

Columbia University Press 2017, pp. 320

ISBN print 978-02311 79966

Review by Alexander Studholme

Tibetans generally like eating meat, though their Buddhist piety has never made this entirely easy for them. The central Mahayana ethic of compassion and the law of karma mean their yak or mutton comes freighted with questions about the suffering involved in animal slaughter and the unpleasant future consequences that may be its result. In this brilliantly researched and beautifully written book, Geoffrey Barstow describes the many different, often rather specious and casuistic strategies Tibetans have used to justify their carnivorous ways and cites numerous pro-vegetarian lamas who have, over the years, challenged this meaty status quo.

As monastics, the Tibetans point to the fact that the Buddha himself was almost certainly not vegetarian and did not forbid his followers from eating meat. When his fractious cousin Devadatta insisted that his own disciples be entirely vegetarian, the Buddha criticised this as too extreme, though he also was pretty strict: his sangha were only allowed to eat meat given to them in their begging bowls, and only as long as it conformed to a rule of threefold purity, namely that the monks or nuns had neither seen, nor heard, nor even suspected that the animal had been killed for their benefit. But according to many ordained Tibetans, for whom begging for food is virtually unknown, this maxim is upheld when meat is bought from a butcher, perhaps wholesale for a big monastery, provided the man in the abattoir had no specific monk in mind while he went about his work.

The Buddha’s rule, originally designed to create an occasional exception for what is morally problematic, has been subverted to normalise meat eating. The same can be said for the Tibetan appropriation of the Vajrayana commitment to eat the five meats: cow, dog, elephant, horse and human. As Jigme Lingpa, the great 18th century Nyingma visionary, explains, the point here is that these things are ordinarily considered to be taboo, and so to eat them in a ritual context becomes a means of participating in the non-dual dimension: “Because they are feast substances, dualistic thinking – such as dividing things into pure and impure, clean and unclean – must be abandoned.” But, as Barstow reports, many Tibetans, past and present, have interpreted this esoteric tantric vow simply as a licence to eat meat on a daily basis, something Patrul Rinpoche rebukes as “behaving carelessly with the tantric commitment of consumption.”

Barstow also examines the Tibetan view that eating meat can, in some circumstances, actually be good for the dead animal. By being devoured by a practitioner, the creature is deemed to receive a cause for a positive future rebirth: liberation through consumption. The prime exemplar of this practice is the mahasiddha Tilopa, who is famously depicted sinking his teeth into a fish that he has just caught, thereby transferring its consciousness to a better life. Barstow looks in vain for any other textual source, but concludes that this perspective is critiqued so regularly by lamas sympathetic to vegetarianism – from different times, places and lineages – that it must have been fairly widespread. Jigmed Lingpa issues a quiet, self-deprecating caveat: “In a tantric context, it’s great if someone… is able to benefit beings through a connection with their meat and blood. But I do not have this confidence.”

Barstow presents Jigme Lingpa as Tibet’s most towering vegetarian figure, who along with other famous lamas such as Patrul Rinpoche, Shabkar and Nyakla Pema Dudul, was responsible for a strong culture of vegetarianism amongst lay yogins in eastern Tibet in the 19th and early 20th centuries. One of the most striking passages in the whole book is Jigme Lingpa’s reflections on seeing a group of lambs awaiting slaughter. “Thinking like this, uncontrived compassion arose,” he writes, “This experience was the most important event of my life.” So moved was he by Jigme Lingpa’s views, the revered, modern day Nyingma lama Dilgo Khyentse “took a vow to eat meat only once a day.”

Herein, perhaps, lies the crux of the book. Although Barstow is himself veggie, his book is never a tiresome polemic. It is, rather, a fascinating social history, in which the phenomenon of meat eating becomes a means of affording fresh insight into Tibetan culture and identity. Dilgo Khyentse’s vow may seem almost comical in its mildness, but it is representative of the kind of many pragmatic compromises that Tibetans took towards what was widely regarded as a necessary evil: moderating one’s intake of meat, saying prayers for the dead animal, cultivating awareness. Barstow acknowledges the “limits of Buddhism” in Tibet, discussing the way in which meat eating is an integral part of other sociological tropes such as prosperity and heroic masculinity.

Barstow concludes by discovering an upsurge of vegetarianism in contemporary Tibet: travelling in Kham, he comes across entirely meat-free monasteries and restaurants with menus divided into “white food” (karse) and “red food” (marse), vegetarian and non-vegetarian. Though this cultural shift is due in large part to the advice of venerated teachers like the Dalai Lama, Karmapa and Khenpo Jigme Puntsok, there are plenty of dissenting voices: the issue is debated passionately in online forums. Vegetarianism, though expressive of the Buddhist values that Tibetans cleave to, is seen as incompatible with other aspects of the Tibetan world, most notably the nomadic way of life, where raising livestock is absolutely central. Pro-vegetarian lamas have had to revise their views in order to support nomadic communities.

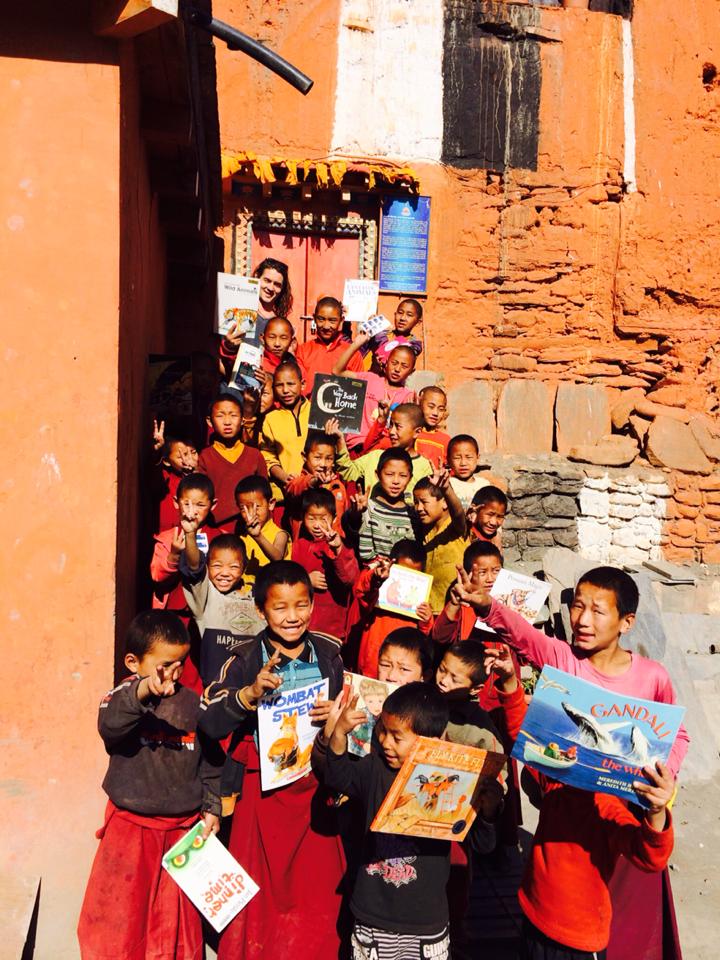

Whilst the harsh environment of Tibet has hitherto made surviving without meat extremely challenging, there is now a much greater availability of fresh fruit and vegetables, as well as improved dietary education. The modern Rime master Khentrul Rinpoche, writing in 2013, notes: “[Until] about eighteen years ago, most of the people in my village didn’t even know that vegetables could be eaten by humans.” However, the meat eaters remain defiant. As one young Tibetan tells Barstow: “Vegetarianism is destroying our culture.”