I was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, into a family of school teachers. During the war, I lived in the village of Dongkurgan near Tashkent, where I grew up absolutely alone, in nature, without tutors. At the age of seven, I attended the first grade in an Uzbek school, and from the second grade on I went to a Russian one, because we moved to the city. Later on I entered medical school and four years after, when I was 21, I left Tashkent for Moscow and entered the biology faculty of Moscow State University. After graduating from university, I went to graduate school and wrote a dissertation on radiobiology at the Department of Biophysics. My dissertation was based on the intersection of sciences: I studied plants that protect against radiation by radio beams. At the age of 42, I defended my dissertation and worked at the biology faculty until my retirement.

At the age of 51, I went to wushu classes with swords, and in our group there was a man named Garab from the Dzogchen Community. One day he came and said, “Tamara, Rinpoche is coming and there will be a retreat. You should be there.” Since it was the first time I had heard the words “Rinpoche” and “retreat” and I didn’t want to study, I didn’t go. But in the group we had a girl called Svetlana, who studied Chinese. She came running to me and said, “Believe me or not, I do not know what it is. It is something I can’t explain or talk about, but I just know you should be there,” and gave me the address.

It was 1992, and Chögyal Namkai Norbu had come to Moscow for the first time. By the time I got there, it was the last day of the retreat. I went up to the fourth floor, to the gym; there was a pile of shoes at the entrance and there was silence. I walked in slowly and saw a white basketball circle in front of me. As soon as I sat in the circle, the hall made a sort of humming sound and it seemed to me that I flew into a space tube. And I’m still flying.

Since it was the last day of the retreat there was ganapuja. My friend Batagoz from Kazakhstan was at the retreat and she came up to me and asked, “Are you a Muslim or not?” I said, “Why?” “There are guests here, they need to be served, get up.” They handed me a bag of nuts, told me not to let it out of my hands and to give them out a bit at a time.

When the Vajra Dance mandalas were laid out, I was completely stunned because this was what I had dreamed of all my life. And Rinpoche danced. There were Prima Mai, Annalen Gall, Anya from St. Petersburg who had already learned to dance. I followed Rinpoche around the mandala, repeating what he was doing.

The retreat was over and Rinpoche was leaving for Lake Kotokel in Buryatia. A magical story happened: in the entire history of Moscow University, I was the only one who took a vacation for a day and received money. Garab helped me buy a ticket.

I arrived in Buryatia. My friends had provided me with a tent and I travelled to Kotokel with some men who gave me a lift on a dump truck and showed me where to go next, to some military sanatorium. I was tired when I arrived there and I still had to put up my tent. I asked where Rinpoche lived and was told that he was on the 4th floor. I went up there, saw a sofa in the hall and decided to rest first and put up the tent later. I fell asleep and slept all night and ended up living there for the whole time as no one kicked me out.

During my first retreat on Kotokel in Buryatia, I received transmission. I quickly ran to Lake Baikal and took a dip. When Rinpoche left, I stayed in Buryatia for some time.

There I lived with my friend, an architect, who worked at a school for specially gifted children, and I taught some classes to them. A few years before that, I worked on Lake Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzia in a rose garden, and with our eyes closed, we would determine the color and shape of roses using our hands. I suggested to my friend buying flowers and holding a similar lesson in the third grade in Buryatia. The flowers were expensive, but there was colored paper. I came to class and told the children that we would work with our hands. I told them to sit up straight and applied everything I knew from qigong and had heard from Rinpoche. I asked them to move apart so as not to interfere with each other, straighten their backs, stretch their heads and sit straight all the time and move their palms until they could feel a ball between them. Then I asked them to put the ball on their tummies. They understood and found it interesting. Then they pinpointed the colors. They said “warm” for red, “cold” for blue, and they wanted to move their hands away for black. In general, the lesson went well, and other teachers began to come to me to study. So I spent a month there and then returned to Moscow.

When I returned, I immediately became involved in the Community. At Rinpoche’s retreat in 1994, the cooks complained that they couldn’t buy any parmesan cheese in time for Rinpoche’s arrival. I helped them and somehow since 1996, I was always in the service team, preparing food for Rinpoche at his retreats in Russia. In 2003, I went to Italy, to Merigar, for the first time together with Slava Potapenko, who organized our trip. I did karma yoga in the kitchen and attended retreats. I lived there for three months and from that moment I began to follow Rinpoche in his travels. By that time I had already retired and had no problems travelling. For a couple of years I lived in the Gar on Margarita Island in Venezuela, I was in the service group in Romania many times and traveled a lot following Rinpoche. It was practically my life, I had no other life.

In addition, since 1996 we studied Santi Maha Sangha using transcripts because there wasn’t any printed literature at that time. We copied everything Rinpoche said by hand. I was working as a watchman at country houses, and I had time to sing and practice all night. My loud singing guarded the suburban areas, especially in winter, when no one was there. I would do all the necessary practices, and then do the exam. Since I am very interested in science, as a researcher, I did not need to be convinced of anything, I immediately perceived it as something necessary, to investigate, to study.

I passed the exam for the base level, the first level, and completed all the practices for the second level. However, a few months before the exam I fell, injured myself and felt insecure. I came to the gakyil and said that I had done everything, but I had some internal trepidation, a kind of uncertainty related to the injury, and they told Adriano Clemente, who was giving the exam. When I entered for the exam, Adriano took his guitar and started singing, and I flew into the cosmic tube again. I took my question; they would first read it out in English and then translate it into Russian. When the question was read in English, I already knew the answer. Adriano had already introduced me to that knowledge. This is one of my stories related to Santi Maha Sangha.

After the fourth level, many of the experiences that I received doing the practices became clearer.

I had no doubt about the Vajra Dance from the first day. When I first saw the mandala and Rinpoche dancing, I realized that this was mine, that this was what I had been looking for all my life. In Kotokel in Buryatia, we danced on a mandala drawn in chalk on the dance floor. Of course, I didn’t have any slippers with me and there was nowhere to buy them there. I went barefoot, studied, and my heels were covered in chalk. I haven’t stopped dancing since. Here in Tenerife I dance every day. For me, this is one of the important practices. I dance the complete thun of Vajra Dance, the Khalong and I practice yantra yoga.

I don’t divide life into ordinary, everyday life and practice. My whole life is practice, and this has been the case since the first meeting with Rinpoche. For me Rinpoche is always there. Maybe this is guru yoga.

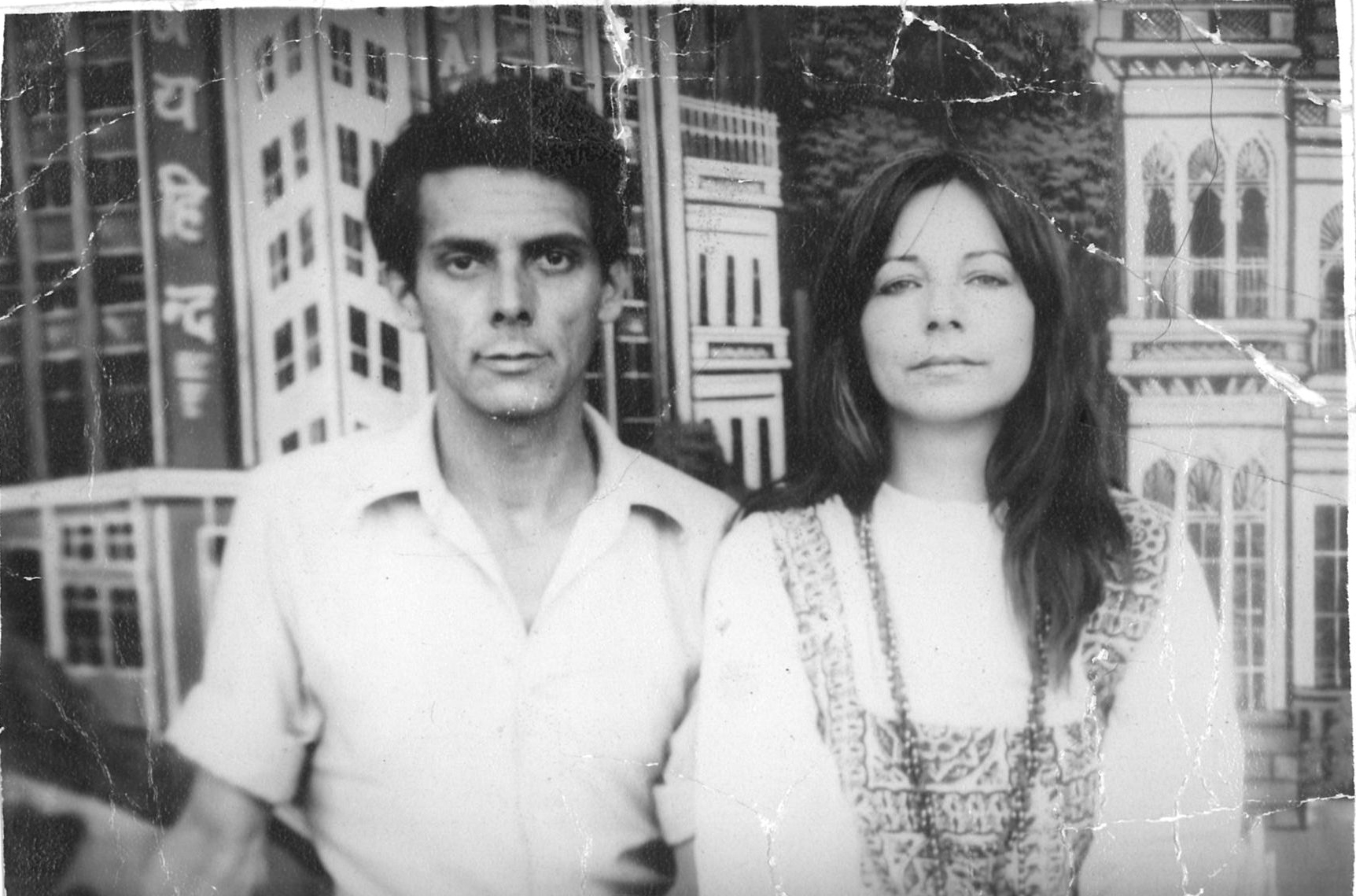

Featured photo by Yulia Petrova