By Emanuele Assini and Basilio Maritano

Introduction

The Tibetan Nomads, usually known as Drokpa (འབྲོག་པ།), are the heirs of a fascinating and ancient way of living that in the past decades has gone through many changes. Their lifestyle is now facing the challenges of modernization, but in spite of this it’s still quite simple and their possessions are few. In the remote grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau, nomads herd yaks, sheep, and horses. Even if most of these groups are now becoming semi-nomadic, they still live in tents for most of the year.

In the tents, they sleep on thin mats around the central stove, where they cook and make butter tea. Their food is usually limited to tsampa, dough made of roasted barley flour, and to dried yak meat and dairy products such as cheese, butter and yogurt. Since there are no trees in the nomadic regions, the main fuel for the stoves is dried yak dung. They live in harsh conditions, due to the high altitude of the area and its cold and long winters, and even though many of them now have homes where they can spend the cold season, their camps are still set up for at least 6-8 months a year.

Nowadays, all the areas of the Tibetan Plateau are still highly populated by nomads, despite urbanization, and many nomadic groups can also be found in certain areas of Sichuan and Xinghai.

Basilio and Emanuele

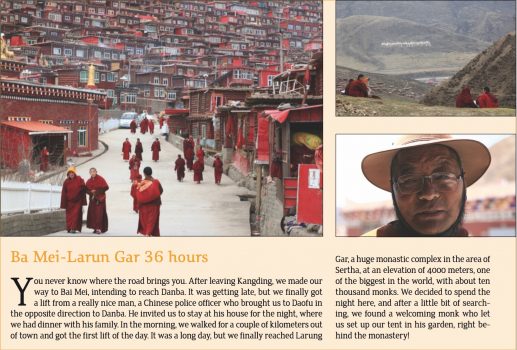

In the past two years both of us, Emanuele Assini and Basilio Maritano, have had the opportunity to get in touch with nomadic customs and traditions during our trips to Ladakh and West Sichuan. Then, in autumn 2015, while living in Vienna, we both read a book by Namkhai Norbu, “Journey Among the Tibetan Nomads”, a summary of the main cultural aspects of the Tibetan Nomads living in the areas of Sertha and Dzachuka. The book is based on the diaries of the then seventeen-year-old Namkhai Norbu, which describe his experiences among the eighteen tribes living in those areas. The book, which addresses a public interested in Tibetan culture, was published by Shang Shung Editions in 1983. This reading, as well as our personal experiences, inspired us to plan a trip among the Tibetan Nomads living in the same areas, with the desire to understand more deeply and directly what is left of their ancient traditions. This is the main reason that brought us to China. We arrived on 20th April 2016, and until the end of June we travelled through West Sichuan and South Xinghai, especially the areas of Dzachuka and Sertha, with the aim of experiencing the traditional Tibetan nomadic lifestyle. During this period we visited schools and monasteries, and spent some time with a Tibetan nomad family, experiencing their culture and collecting stories and visual material.

Today is the ninth of June. We have been in China in the Tibetan Provinces of Kham and Amdo for almost seven weeks starting eight months ago when we began planning this trip that is now coming to its end.

It seems like yesterday we were in Vienna discussing the possibility of starting a project in this area. Everything seemed so far away and unreal that only our imagination could make it happen. Instead, here we are, today writing this report of what has been, until now, a few intense weeks before the end of our journey. With no small sadness we realize how time has flown without our noticing it and in a short time we will be returning to Europe full of memories and materials to work on and develop.

Inspired by the book “Journey into the Culture of the Tibetan Nomads” by our Master, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, and full of memories of our preceding experiences with the Tibetan people, we took our backpacks, filled them with photographic equipment and lots of good will, put them on our shoulders and flew to China at the end of April. We had heard much fascinating information about Tibetan nomads which inspired us to begin this project with the desire to understand about the reality of the nomads of today and be able to share the results of our work with the Dzogchen Community. Obviously many things were not as we expected and this only made it more interesting, to the point of considering the idea to return again.

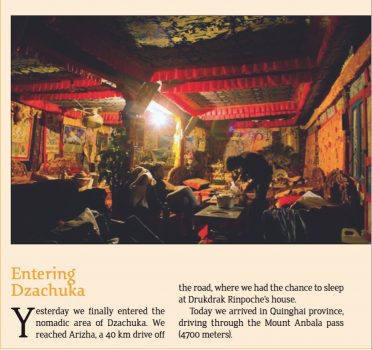

By the end of April, after a few days of preparation, we left Chendu, the capital of Sichuan. Àfter a six hour bus ride, we arrived in Kangding, the point of entry to the province of Kham. It was our choice to travel by hitchhiking so we could save money on transportation and also have immediate contact with the local people. We could not have chosen better. Full of baggage and knowing only a few words of Chinese and Tibetan, we were helped in each part of our long journey. Today we can say definitely we hitch hiked at least 3000 kilometers along the road that goes from Kangding to Xining and returns to Chendu, across canyons, high mountain passes and the vast grasslands of the Tibetan plateau. With the eyes of two young travelers open to cultural impact, we crossed a large part of Tibet “open” to strangers, asking questions, observing, listening to every opinion, and discovering something new every day. We tasted the hospitality of a culture that, divided between grasslands and resettlements, between mountains and cities, and mixed with different ethnic groups, is moving in an uncertain direction which I dare say will be full of surprises.

Throughout our travels, thanks to hitch hiking, and some good fortune, we met with many diverse people and we heard many different opinions. From the Chinese policeman who offered us hospitality to the old monk who let us put up our tent in his garden, to the nomad returned from India less than a year ago after 20 years of absence, all the people we met shared with us their point of view giving us the chance to learn more about this culture in the process of change.

It is a pleasure for us to share these experiences with the readers of The Mirror, besides giving us the possibility to remember these very important moments in our travels and fix them on paper. For this reason we have decided to write about a brief episode that happened in the last few days which for us was very meaningful, instead of giving a step by step account of our trip overlooking moments of rich significance.

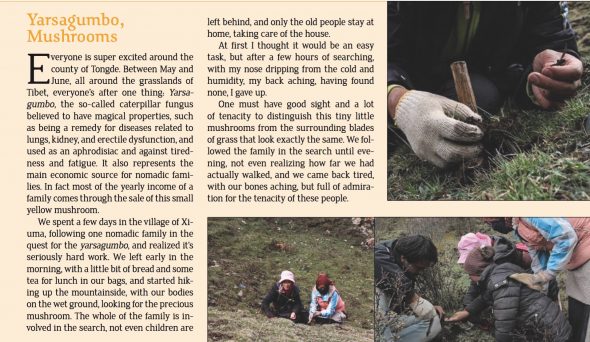

A few days ago, after a long trip with only a few short stops, we arrived in the village of Xiuma, where we had the pleasure to spend a few days in the company of an elderly nomad named Aolei, staying in his house, 30 minutes outside the village. After a few days we became familiar with his routine and discovered many interesting things.

In this period, all nomad families are busy searching for yarsagumbo – caterpillar fungus. This small and expensive fungus often represents 80% of the yearly income for these families. For this reason during the yarsagumbo season, even children are busy searching for it. Only elderly people remain at home to take care of the household duties while the rest of the family spends the days climbing the surrounding mountains with their eyes fixed on the earth.

So we found ourselves alone with Apa Aolei, a cheerful old man extremely happy to have us as guests. Self-educated and very dedicated to fulfilling his religious practice during the day, Aolei told us a lot about his youth and his family and gave us very interesting opinions regarding the cultural changes happening in Tibet.

Apa Aloei explaining the mo

We were very struck, upon entering his house, at the number of books on the typical wooden shelves where they usually keep photos of the Masters, the Dalai Lama, religious scriptures and various other objects. We visited many other families in that area and rarely we saw more than a couple of books in the house. So we were curious and asked why. We were told that many of these books were classical, historical and religious texts written by scholars who are very famous in Tibet and China. Not only that, one of his two sons was now in Japan to complete his studies, something very rare in this area.

Not having the possibility to go to school, it was very important to Aolei that at least one of his sons receive a good education and in this he was satisfied. The whole bookshelf was about 5 meters long and besides being full of books and objects, it was covered with badges and trophies collected by his son during his scholastic pursuit. Not only this, but many of these badges were higher on the shelves than the Buddhist texts and the photos of the Masters would usually be placed. This was an evident sign of how important education was considered in his home.

Again our curiosity posed more questions.

Apa Aolei had lived through the Cultural Revolution when he was 8 years old, the son of a nomad family that lived in a tent all year around. When he was an adolescent, just after the “revolution” his life was extremely poor and they passed the rigid Tibetan winters in a tent with very little food. Nevertheless, his memories are positive telling us about the nomadic costumes and the traditional tents made of yak hair and how the land was still equally shared by all the inhabitants of the village. Today, every single piece of grassland has been fenced in by the Chinese government. Every single member of the family had to learn to do all types of work like spinning yak wool for clothes or putting up a tent or building the kitchen out of mud; things that the new generation now don’t know how to do.

When his children were born, with the help of government subsidies, his family was able to build a house for the winter. The majority of nomad families live like this today; in houses for the winter and in tents in the summer. Now the tents are modern structures and easier to put up.

Regarding the religious life, Aolei is an extremely dedicated man. While not having had the possibility to go to school, he educated himself so as to be able to read religious scriptures. With great honesty, he told us how he was not able to acquire a deep knowledge of Buddhism but as years went by he felt the capacity to be able to divine the future using dice. This practice is called Mo and is usually reserved to monks and lamas for making important decisions. It is said that the answers read from the dice come directly from Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. After the Cultural Revolution, practicing religion posed many problems. Aolei tells us that in the 70s, families would often meet in secret to practice far from the eyes of the Chinese. Today, he tells us, fortunately we can practice freely.

Aolei told us many things, too many to put in one article. It was a great experience for us to be with him and listen to his point of view about the changes in the last fifty years.

In conclusion, we would like to share a metaphor he used to respond to our question “What would you like to say to the world and to the people who will read this interview?”

It made us smile and think deeply of the cultural changes in the high plains of Tibet where the new generations will hold great responsibility for the future. After having spoken about the evolution of the culture in Tibet and of the differences compared to the years of his youth, Aolei wanted to leave a message for young people regarding the continuing of traditions in the years to come.

Somewhat paraphrasing, this is what he said: “In my youth, when nomad families killed a sheep to eat, we used every single part from the head to the skin so as to not waste the life of this animal, even though it often meant a lot of work. Young Tibetans should, in the same way, conserve their traditions, without ignoring any aspect of their cultural inheritance just because it might be uncomfortable; for example, traditional Tibetan dress might be considered out of style or too heavy. They should continue to eat tsampa, dress themselves traditionally and preserve their cultural values.”

Aolei walking alone

We believe this affirmation, in its simple way, hides many questions that should be reflected upon, in order to understand closely the reality of the nomads today. From our side, we are doing everything to return home with a complete vision that we hope to share with the members of the Community.

Translated from Italian by Carol Chaney

You can also read this article in:

Italian