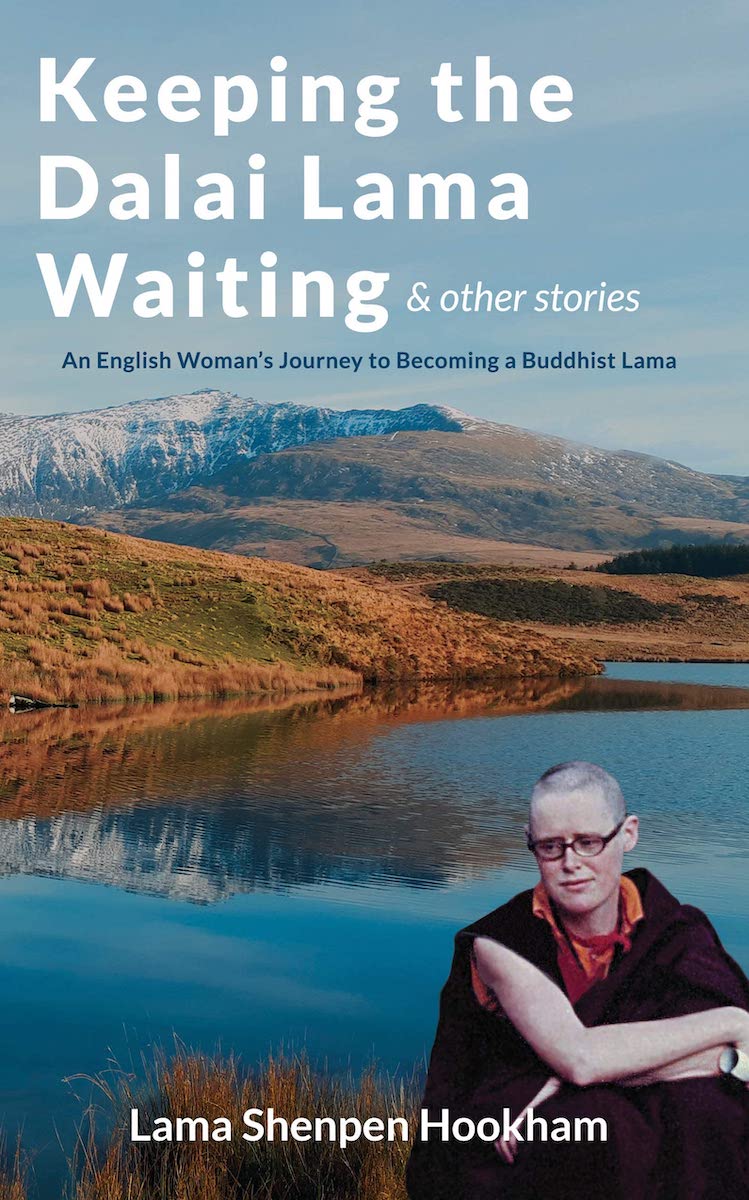

An English Woman’s Journey to Becoming a Lama

Shenpen Hookham

Shrimala Publishing 2020

pp. 337

ISBN 9798617593411

Lama Shenpen Hookham is a member of that small, select band of adventurous western women who travelled to India in the 1960s to live with the exiled Tibetans, ordain as nuns and, eventually, become Buddhist teachers in their own right. Like Tsultrim Allione, Tenzin Palmo and one or two others, she has a remarkable tale to tell – of a life lived in complete dedication to the dharma, inspired by the unprecedented access she had to some of the great Tibetan lamas of that era. Her memoir is a precious record of that time, deeply insightful about Tibetan Buddhism and wonderfully entertaining. A succession of first class anecdotes – the calloused foot that breaks through the ceiling of her retreat hut one night, the story of Lama Phurtse sneezing over the breakfast tray, the Karmapa and the Japanese drum, to name but three – are all relayed with great verve and wit.

Lama Shenpen Hookham is a member of that small, select band of adventurous western women who travelled to India in the 1960s to live with the exiled Tibetans, ordain as nuns and, eventually, become Buddhist teachers in their own right. Like Tsultrim Allione, Tenzin Palmo and one or two others, she has a remarkable tale to tell – of a life lived in complete dedication to the dharma, inspired by the unprecedented access she had to some of the great Tibetan lamas of that era. Her memoir is a precious record of that time, deeply insightful about Tibetan Buddhism and wonderfully entertaining. A succession of first class anecdotes – the calloused foot that breaks through the ceiling of her retreat hut one night, the story of Lama Phurtse sneezing over the breakfast tray, the Karmapa and the Japanese drum, to name but three – are all relayed with great verve and wit.

She vividly conveys the extraordinary ambience of the lamas. Karma Thinley Rinpoche is eccentric – feeding slugs and lobbying the US embassy to put a vast image of the Buddha on the moon – but no less impressive. “He could suddenly switch,” she writes, “and you got a blast of power as he took on the role of the Primordial Buddha.” Kalu Rinpoche has a haunting presence, “radiant, with a gentle but wry smile”. Dudjom Rinpoche speaks to her softly and tenderly, “as if from a different dimension of space”. She takes ordination from the Karmapa himself, who intuits her deepest wish in his first glance, declaring spontaneously: “Beyond meditation and non-meditation, then you can help everyone effortlessly.”

In the end, she becomes closest to Bokar Rinpoche, who, fresh from a long retreat, has the time to help her with translation and work through her questions. Shenpen is not a woman to take anything for granted. “This was not what I had come all the way to India to hear,” she remarks about the traditional teachings on the hell realms and her interrogation of the Tibetan worldview is often illuminating. She is very good on the emphasis on accumulating punya or merit, and on developing tendrel or auspicious connections. She describes the way a belief in karma and reincarnation creeps up on her, absorbed as if by osmosis, until she discovers one day that she has developed renunciation. And she shares with the reader her first glimpses of the nature of mind. “It is like a strong man wrestling with a weaker man,” Bokar explains, “Eventually the strong man gets weak and the weak man strong. Then it is easy.”

Her experiences in India have an exalted, providential quality. “Time stopped,” she writes of her arrival, “and didn’t speed up again till I set foot in Heathrow airport five and half years later.” A generous ex-boyfriend sponsors her financially, allowing her to feel completely free. Her prodigious appetite for solitary meditation is seen by the Tibetans as the result of a past life and almost from the start, the lamas – including the Karmapa – assume she will return to the west to teach. This sense of destiny is perhaps most sharply felt in a mysterious encounter with Thukse Rinpoche, who asks what her Tibetan name is. “No, it’s not,” he replies, when she tells him, “it’s Shenpen Zangmo.” Shenpen, meaning “benefit others”, is the name she has used ever since.

Back in the west, things do not run so smoothly. She struggles with the tension between following the advice of the lamas and discovering her own autonomy. “I had put myself under the direction of people who didn’t know what they were doing,” she writes at one point in exasperation, “so it was up to me to work something out for myself.” She finds stability for a while as translator for Gendun Rinpoche in the south of France, but the peculiar demands of this role are sometimes overwhelming. Then, when she meets her main teacher, the yogi and scholar Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche, she is told to stop being a nun and return to lay life. Her account of how she negotiates this difficult transition with her new guru is particularly candid and revealing.

Under Khenpo Tsultrim’s guidance, she completes a doctorate at Oxford, a groundbreaking study of the Kagyu philosophy of Buddha Nature, published in book form as The Buddha Within, at a time when Tibetan academic studies were still very much dominated by the Gelugpa view of emptiness. There, she meets and marries another western yogi, Michael Hookham, who does a three-year retreat in his semi-detached house. Initially, the two of them work together to foster a community of students called the Longchen Foundation, but the marriage founders and she strikes out on her own to create her own organization, the Awakened Heart Sangha.

When Shenpen was a little girl, the thought that she would become a nun came to her suddenly while doing a handstand in the school playground. “I am an old lady now,” she writes, “living in semi-retreat in the wilds of north-west Wales.” This is an outstanding dharma book, profoundly thoughtful, original and funny, a brilliant encapsulation – in one woman’s life story – of the western encounter with Tibetan Buddhism, and like any good spiritual autobiography full of inspiring and helpful teaching, not least the impressive example of unwavering diligence and enthusiasm she demonstrates throughout.

By the last chapter, Bokar Rinpoche is dead, struck down suddenly at the age of 64. Shenpen writes movingly of attending his funeral, accompanied by various miraculous phenomena, where she is given some of his relics. Khenpo Tsultrim, too, though still radiating an amazing spiritual presence, appears to have entered an advanced state of senility, his behaviour becoming ever more bizarre. Having travelled all the way to Kathmandu to see him, Shenpen is handed a big bag of apples by her guru and told to eat them all, meditatively, in his shrine room, savouring every morsel. Setting obediently about the task, she asks, “Did he somehow know I hate apples?”

Review by Alexander Studholme