an Outstanding Twentieth-Century Tibetan Woman.

by Iacobella Gaetani

The following article is an excerpt of The Luminous Necklace of Pearls, a paper by Iacobella Gaetani contained in Garuda Verlag’s 2016 publication Sharro, Festschrift for Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. This compendium of writings is a token of appreciation for Rinpoche’s lifelong dedication to the preservation of Tibet’s endangered cultural and spiritual heritage. The Luminous Necklace of Pearls introduces the life and poetry of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s elder sister, ‘Jam-dbyangs Chos-dbyings sGron-ma. Due to limits of space, we are publishing this reduced version of the paper devoid of its clarifying footnotes.

Iacobella Gaetani graduated from Naples Orientale University and among other Tibetan texts she has translated Rinpoche’s The Practice of Long Life of the Immortal Dakini Mandarava and The Temple of Great Perfection, The Gonpa of Merigar.

Introduction

In this paper I intend to introduce the life story of a remarkable Tibetan woman, ‘Jam-dbyangs Chos-dbyings sGron-ma (hereafter ‘Jam-chos) the elder sister of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, drawing mainly from her poetry as a source of reference. ‘Jam-chos’ life reflects the dramatic changes that took place in her country in the twentieth century, from a privileged upbringing spent at the court of the sDe-dge royal family, through adulthood as a young learned, respected and independent woman, to long years of confinement and house arrest when her country was shaken by political unrest.

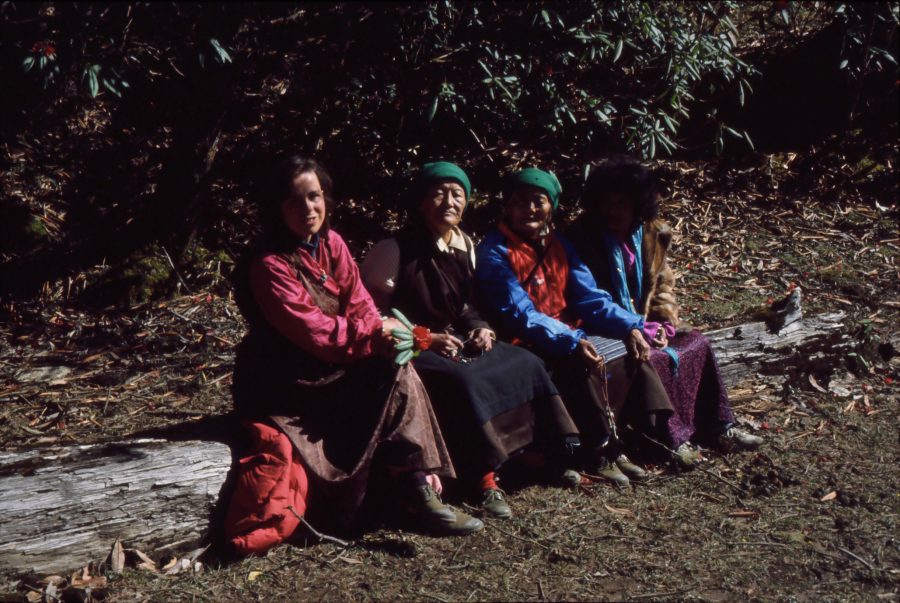

I was fortunate enough to meet her in 1984 during a pilgrimage to Māratika in Nepal led by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. On that occasion I had the chance to appreciate her strength and resolution which despite her age, enabled her to walk from the small airport of Lamidanda, on a four day arduous hike… In the evenings during the quiet moments around a campfire after a long days trek, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu would give us short glimpses into the extraordinary life of his elder sister. With admiration he would tell us of her knowledge and skills in Tibetan literature and poetry quoting ‘Jam-chos’ poem ‘Invocation for my daughter g.Yu-sgron Lha-mo who has gone beyond’ as an example of a perfect Tibetan poem where emotions and feelings are subtly hinted at, veiled behind metaphors…

Her poetic works, which I will briefly introduce here, help us understand the remarkable story of an educated and religious woman who since early childhood was destined to play a significant role in the history of her country while also revealing her deep devotion and commitment to the spiritual path…

Life and Times of ‘Jam-dbyangs Chos-sgron

The main sources for this short introduction to the life of ‘Jam-chos are her poetry, mainly her autobiographical poem entitled ‘Sincere Verses about My Experience’ (Rang myong gi drang gtam tshigs su bcad pa bzhugs), found in her collection of poems called ‘Jam chos rtsom bris phyogs btus bzhugs, and on a series of interviews with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu recorded on different occasions, in which he narrated his eldest sister’s life story.

‘Jam-chos was born in 1921 in dGe-‘ug in lCang-ra, a district in sDe-dge, into the Nor-bzang family, the eldest daughter of Tshe-dbang rNam-rgyal and Ye-shes Chos-sgron. Her beloved maternal grandmother was Lhun-grub-mTsho, a great Dzogchen practitioner who considered ‘Jam-chos to be the incarnation of her teacher, the yogini A-phyi ‘Ug-sgron. Her maternal uncle was the great master mKhyen-brtse Chos-kyi dBang-phyug, whom she devoutly assisted until the end of his life. Her brother was Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, whom she loved dearly, and her paternal uncle was the accomplished master rTogs-ldan U-rgyan bsTan-bdzin…

Thanks to her father’s ties to the royal family of sDe-dge, ‘Jam-chos was permitted to study at the court with the prince and the three royal princesses under one of the greatest scholars and masters of her time, Khu-nu bLa-ma bsTan-‘dzin rGyal-mtshan, who was born in Khunu in India…

She studied grammar, the five traditional Tibetan sciences, Sanskrit and poetry from this master and soon became his best student. She lived at the court until she was sixteen and became a close friend of the prince and princesses. During that period she befriended bDe-chen Lha-mo, the daughter of a well known lama, ‘Jam- dbyangs Grags-pa. Her friend proposed that she become a nun in order to be able to study the Kālacakra Tantra and the instructions on astrology related to it, with her father. Encouraged also by her parents, she took monastic vows and followed her friend. She stayed about two years at ‘Jam-dbyangs Grags-pa’s monastery to receive teachings and instructions and to practice.

When she was eighteen years old ‘Jam-chos gave up her robes, let her hair grow and renewed her friendship with the princesses of sDe-dge. Not long after, she started a relationship with Tshe-dbang bDud-‘dul, the king of sDe-dge:

Thanks to the benevolent assistance

of the sun-like blazing king

Tshe dBang bDud ‘dul

I had the opportunity to unfold the lotus of knowledge.

Regarding the general reactions to her disrobing she writes:

When I was eighteen years old

although many people disapproved of my decision

to renounce my nun’s vows for some time,

your (the king’s) attitude towards me didn’t change.

From these verses we can understand that besides the king, most people did not approve of her decision. A woman at that time had only two possibilities: either to marry or to become a nun. ‘Jam-chos chose to distance herself from the socially accepted custom and entered into a difficult relationship with the most prominent man of her country, the king.

After the king’s arranged marriage to one of the princesses of the nearby kingdom of Nang-chen, ‘Jam-chos continued her relationship with him in secrecy until discovered by the new queen. At that time ‘Jam-chos started to lead an active political life.

As she mentions in her verses:

To increase positive circumstances

in the mundane condition

I became involved in beneficial politics,

which awarded me with many gifts.

From these lines one can infer that although she played an active role in the political scene of those years in her country, the motivation behind her mundane activities was the Mahāyāna vow of acting for the benefit of all sentient beings…

Describing ‘Jam-chos’ public and family role, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu told us that although she was very attractive and admired by most ministers, she developed a sense of independence and authority uncommon for women during that time in Tibet. She dressed as a traditional eastern Tibetan woman but carried a pistol and rode the best horses available in the country. A part of this independent and self-determined attitude was her decision to not get married, the same decision that initially led her to become a nun in order to continue her studies and spiritual quest and later determined her choice of rejecting various suitors.

Distanced from the court, ‘Jam-chos’ family which until then had been associated with the Aja ruling family, sought alliance with a rival faction headed by the minister Bya-rgon sTobs-ldan.

Soon the family became an easy target for an unscrupulous member of a powerful noble family who tried to seize a piece of land that the Nor-bzang had just bought. As her father did not want to get involved in a dispute, ‘Jam-chos resolved the case in a very bold and direct way: she set fire to the crops grown by the other family on their land.

Soon after this incident, against her father’s wishes, she fell in love with Sri-gcod rDo-rje, the younger son of an impoverished noble family. They had a child, a young daughter. A smallpox epidemic broke out in the region and the child died shortly after, when she was only one year old. This left ‘Jam-chos devastated. Thus she expresses her grief:

My beloved g.Yu-sgron Lha-mo!

Although one can’t bear to be separated from one’s heart

the conditions that broke my heart

caused me such sorrow that I lost my own heart.

On the tomb, placed in the wall of the family house, where her daughter’s body was laid inside a small coffin covered with salt crystals, she inscribed the words of the poem ‘Invocation for my daughter g.Yu-sgron Lha-mo who has gone beyond’ that she composed shortly after her daughter ‘s death:

You, my beloved one,

beautifully adorned by an iridescent (pan dza li ka) cloth

while you were peacefully sleeping for some time

I understood a warning of time.

Even though from the garden of beautiful lotuses

the pollen of the white magnolia flower

did not blow in my eyes,

a luminous necklace of pearls has fallen from them.

Although you have passed away

you are still present in my mind

I pray that I will meet you again in your next life.

With the death of their daughter, ‘Jam-chos and Sri-gchod rDo-rje ended their relationship. ‘Jam-chos totally devastated, turned her back on worldly commitments, and decided to dedicate herself to the spiritual path by following the teachings of her uncles mKhyen-brtse Chos-kyi dBang-phyug and Togs-ldan U-rgyan bsTan-bdzin by entering retreat for a year. Since her uncle mKhyen-brtse, as time passed, was spending most of his time in retreat in the mountains, he decided he didn’t need an administrator anymore to run the main monastery’s proprieties and herds, of which he was the head. ‘Jam-chos realized that now, without anybody overlooking the management of the monastery’s livestock, her uncle’s means of sustainment were in danger. Therefore she left the capital and lived for many years at sGa-gling-steng.

With the deterioration of the military and political situation in sDe-dge, many lamas and families were in danger. ‘Jam-chos’ family including the young Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, decided to leave for the relative temporary safety of Central Tibet. mKhyen-brtse did not want to leave. ‘Jam-chos decided to remain with him to look after him. Not long after, mKhyen-brtse was arrested. ‘Jam-chos and many devoted local people forced their way into the jail and released him. Pursued by the army, they escaped onto the grassland and lived among the nomads for many months. On March 13, 1959 they were finally captured on the banks of the Yangtse River while mKhyen-brtse was conducting the funeral rituals for rDzogs-chen Rin-po-che who had just died.

‘Jam-chos was also captured and taken to the prison of sDe-dge rDzong where she was condemned to forced labour. She could however, still get messages to her teacher and relay messages from him to those with whom he wished to communicate. He asked her to relay a message to two great masters, rDzogs-chen ‘Brug-sprul Rig-‘dzin and Zhes-chen Rabs-‘byams, who were in the same prison. The message was one phrase. ‘Jam-chos delivered the message. On the following morning, all three teachers were found dead in meditation position.

Her teacher, whom she had served loyally and for whom she had endangered her own life and accepted imprisonment, had passed away. Thus she describes her trials and punishments:

The little knowledge I have, I gained

through the kindness of my wise parents.

However the ones who don’t possess knowledge attacked me

accusing me of being an intellectual belonging to the ruling class.

Later, as part of her internment, she was assigned the task of raising pigs. She was required to find food for them from by finding them the leftovers from the military quarters, offices and school kitchens. Even in these difficult circumstances, she was able to excel. So soon from the initial nine pigs in her care she managed to raise eighty-four fat pigs. As a reward, the Chinese officers released her from forced labour.

‘Jam-chos now free, wished to join her dispersed family in Lhasa. However she had no money. So by collecting grass and wood in the mountains to sell to travelers on the main road to Lhasa, after three months of hard work, she managed to save enough money to reach the capital.

After much hardship, finally ‘Jam-chos arrived in Lhasa, only to learn that some of the members of her family were dispersed and that her youngest brother and father had died.

At this point, ‘Jam-chos was determined to help her two sisters assist their old and suffering mother. However, shortly after her arrival, some local people reported her to the authorities. ‘Jam-chos was again imprisoned, tried and held under house arrest in a small hut for seven more years. In isolation, ‘Jam-chos continued to compose poetry and to practice meditation.

‘Jam-chos was only able to perform the death ritual for her mother from her unusual retreat place. She remained under house arrest until 1978. After so many years of hardship, finally in 1982 ‘Jam-chos was able to embrace her beloved brother Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, who had managed to come to Lhasa with his Italian family. ‘Jam-chos could also enjoy meeting her nephew, mKhyen-brtse Ye-shes for the first time, the young reincarnation of her late master, ‘Jam-dbyangs Chos-kyi dBang-phyug. For ‘Jam-chos it was like a dream come true! In 1984, as mentioned earlier, ‘Jam-chos and her sister bSod-nams dPal-ldan flew to Kathmandu to join their brother on a pilgrimage to the sacred Long Life Cave of Māratika. ‘Jam-chos died a year later in 1985 in Lhasa.

Poetics

‘Jam-chos’ collection of writings, ‘Jam chos rtsom bris phyogs btus bzhugs, can be divided into two parts: the first one includes several poems and invocations by her grandmother Lhun-sgrub-mtsho and poems written by ‘Jam-chos before 1951; the second part are poems composed by ‘Jam- chos in Lhasa during the years of her confinement. Because she had lost the use of her right hand, she dictated her poems to mKhan po Kar-ma bkra-shis who wrote them down. Later on Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, to whom ‘Jam-chos entrusted the manuscript, edited it and eventually made a digital version out of it. He then kindly provided me with a copy. To better understand and appreciate ‘Jam-chos’ poetry it is worthwhile to briefly introduce the art of Tibetan poetry.

Tibetan Poetry can be divided into three broad genres: glu, mgur, and snyan ngag. Glu which is still used today in Tibetan as a general word for song, is the most ancient and indigenous form of orally sung poetry. Mguror ‘spiritual songs’ initially also sung, were later written down as in the famous devotional songs of Milarepa.The Tibetan term snyan snag, that literally means ‘melodious speech’ is the translation of the Sanskrit term kāvyá and may be both spiritually inspired or secular. Snyan ngag appeared in Tibet after the thirteenth century when Daṇḍin’s seventh-century handbook on Sanskrit poetics, the Mirror of Poetry (Kāvyādarśa) was introduced into Tibet… Kāvyá is characterized by elaborate metaphors and similes, allusions and rhetorical adornments (alaṅkāra). Daṇḍin’s text was meant to be a handbook to teach poetry and to list the various embellishments (alaṅkāra) which include: thirty-two types of similes, hyperbole, double meanings, various types of rhymes and the repetition of sounds and syllables. For each of these Daṇḍin gives examples. He lists, for instance, twenty-five ways to compare a beautiful face to a lotus flower.

It was the Sa skya master and scholar Sa-skya Pandita, (1182-1250), who introduced Daṇḍin’s work in Tibet by including excerpts from the Mirror of Poetry in his famous Entrance Gate for the Learned (Mkhas pa rnams la ‘jug pa’i go). Thereafter, this text was translated into Tibetan repeatedly over time… From the thirteenth century onward, Tibetans resorted, in writing poetry, to the four-line stanza, the Tibetan version of the Sanskrit ślokaḥ, used in kāvyá, the “ornate poetry”.

Ślokaḥ, the Sanskrit verse, consisted of two sixteen-syllable lines of two eight-syllable sections (pāda) each. Thence Tibetans, accorded to each pāda, a full line of an equal number of syllables, mostly seven or nine. Within the ślokaḥ and four-line structure, ‘Jam-dbyang Chos-sgron mastered most of the embellishments such as starting each line with the same syllable or word, repeating the same syllable or word in each line and the use of the alphabetical poem or acrostic (ka rtsom, ka bshad). The latter consists in writing a thirty line poem where each line starts with one of the thirty letters of the Tibetan alphabet, starting with the first Ka and finishing with the last A. Each letter has to have a complete meaning as in the poem ‘The little song to remember the kindness of my grandmother, Lhun sgrub mtsho’ (Aphyi lhun sgrub mtsho’i bka’ drin rjes dran gyi glu cung bzhugs).

I will conclude this paper with the poem entitled ‘Brug chen zhabs drung rin po cher phul ba’i legs skyes tshigs su bcad pa bzhugs (Verses as a gift offered to ‘Brug chen Zhabs drung Rinpoche), dedicated to her brother Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, in which ‘Jam chos expresses the deep love she felt for him and for her special family:

With devotion holding my hands joined at the heart, I pay homage

To Chögyal Namkhai Norbu,

Manifestation of Bla ma ‘Grol ‘dul

Lord of the mind teachings of Samantabhadra.

I believe that it is so very rare to find

In the three worlds, someone like you

That enlightens, with the state of Samantabhadra,

The great darkness of the widespread five defilements.

I also never had doubts

On what the supreme conqueror Karmapa

Predicted clearly

That your enlightened activities will spread everywhere.

Even if the sound of the tampura of your profound teachings

That completely liberates the nature of the mind

Briefly arrived to my ears

Only a small part reached my mind.

I who am extremely entangled in samsãra,

Even if it is difficult to follow you now,

I pray to obtain the good fortune

To one day find the state of my mind.

I hope that you, supreme glory of the teachings,

Will remain, with your lotus feet, firm in the dimension of the vajra,

And that your activities, for the teachings and for the sentient beings,

Will spread in space

Without obstacles, spontaneously.

Brother born from the same parents

For a long time we all have been together

Even if for a while we had to be separated because of karma

I pray that soon we will be together again.

Featured photo: Iacobella Gaetani, ‘Jam-chos and her sister Asod or Sodnam Palden, Nepal 1984 taken by ChNN.