Renewing The Bond Of Deep Sacred Trust

Photo reportage: Chogyal Namkhai Norbu’s 1987 Visit to Samye Monastery, Tibet.

John Shane Text and photos (except photos of family and Rinpoche as professor) © John Shane

Listen to this article

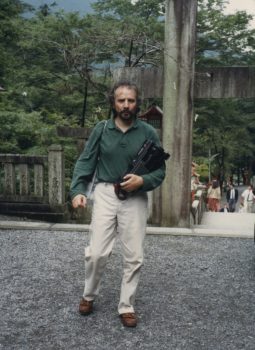

In 1987 and 1988, and also later in 1991, I traveled around the world with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, and wherever we went I carried with me – in a heavy-duty suitcase – a Sony 8mm camera, boxes of video cassettes, a small external video monitor, microphones, and a VCR, as well as other equipment that I used for recording and on-the-spot editing.

But, while I did occasionally shoot video of Norbu Rinpoche when he was giving teachings, the responsibility for recording the teachings was mainly taken by others, and I mainly used my camera to record what we did when Rinpoche wasn’t teaching.

When I began to travel around the world with Norbu Rinpoche, I always carried my trusty Sony video camera with me.

The video tapes I shot in those years have been digitised and during the last few months here at my little studio in London I’ve been viewing the files of the footage I shot as we traveled from country to country, and as I watched the videos I made screenshots and wrote notes to help me recall what’s in each digital file.

Looking at the screenshots after I’d made them, one thing I couldn’t help but notice was how playful Rinpoche always was, whatever we were doing and wherever we were in the world.

No matter what country we were in, no matter who we met, Rinpoche would always find some game to play, some trick to show us, some song to sing, some joke to tell, some improbable adventure on which to lead us.

Norbu Rinpoche was, of course, a profoundly serious person in every way, but, as I viewed the videos from our travels over and over again while taking screenshots from them, the thought came to me that Rinpoche’s seriousness and the playfulness that I was noticing when I watched the videos were actually inseparable, and that his extraordinary playfulness was actually the outer aspect of his profound inner seriousness.

Watching him laughing and joking in so many of the videos as he engaged with so many different people in so many different circumstances, I began to feel that it was the profundity of his inner seriousness that enabled him to carry out every outer activity so playfully.

It occurred to me then that what gave Rinpoche the inner freedom that enabled him to be able to play so freely in the world was his complete realisation of the emptiness of all phenomena, his unshakeable understanding that everything arising in his field of experience was the play of the energy of his own primordial state.

In other words, his profound inner seriousness manifested outwardly in his living his life with an utterly confident spontaneous playfulness.

Of course, this is just a subjective impression that I formed from observing Rinpoche closely in his life and then, more recently, watching the videos I shot while traveling with him.

Others who were close to Rinpoche and knew him well may have formed other impressions.

I can only speak for myself, and I do so accepting that I may be wrong.

But it seems to me that it was because Rinpoche recognised everything arising in the field of his experience as the play of the energy of the primordial state – his natural condition – that he was able to simultaneously carry out so many activities in the world with such precision and to carry such great responsibility so lightly.

Norbu Rinpoche’s life was a life of commitment to others.

His whole life was a mudra of commitment. By ‘mudra’ I mean here, rather than just a shape made with the hands, a complete gesture made with one’s whole being.

Rinpoche’s life was a mudra made in fulfilment of his vow to live for the benefit to all beings, a fundamental aspect of his Samaya.

But, while one might see a spiritual commitment or a sacred vow in terms of it being a binding obligation and thus as something very heavy, it seems to me that a major part of the total gesture of Rinpoche’s commitment – his Mudra of Samaya – was lived out in the playfulness with which he fulfilled his many obligations.

As I see it, this playfulness in action was what enabled him to do so much with such grace. He was able to offer personal advice to so many people, to give so many profound teachings for so many years, to found and manage so many centres in so many different countries with different laws and customs, and at the same time also to write so many books, because he could do it all playfully.

But, while the profound seriousness of Rinpoche’s commitment to the Dzogchen teachings and to bringing those teaching to others is – rightly – always commented on in written accounts of his life, it seems to me that the extraordinary playfulness that accompanied his seriousness can tend to be overlooked when people write about Rinpoche, and that’s why I’m making a point of focussing on it here.

In due course, I plan to edit, color correct, and create audio commentary for the video footage that I shot in different parts of the world so that the videos can be enjoyed by others and perhaps others, seeing the video, will also be reminded of Rinpoche’s playfulness in action.

But, in the meantime, the best I can do, as part of my own Mudra of Samaya, is to share with you some of the screenshots that I’ve recently made, as a way to renew the bond of deep sacred trust that we individually and collectively share with each other through our own and others’ connection to Norbu Rinpoche.

But rather than including screenshots from video recorded in several different countries, I want to focus on footage that I shot in in one place, and, in honor of Norbu Rinpoche’s country of origin, the screenshots I’ve chosen to include here are taken from video I recorded during the four months that I spent traveling in Tibet in 1987 with Rinpoche and a small group of his other students.

At that time, after years of there being either no possibility of traveling at all in Tibet, or there only being the possibility of traveling in Tibet with the constant supervision of a government official as a guide, the possibility of traveling freely in Tibet opened up for a short while and, during our four months in Tibet, we were able to travel wherever we wanted without a tourist guide or an official supervising us.

For Rinpoche, despite the fact that there was an element of sadness for him in seeing his native country in the difficult situation in which he found it when he returned there, it was a carefree, joyful time – a time during which he renewed his contact with family members and friends who had remained living in Tibet, and a time in which he also renewed his connection with the culture of his native land, renewing in particular his connection with one of the most important sacred places associated with many of the spiritual traditions of which he was such a great exponent – Samye Monastery – the first Buddhist monastery that was founded and built in Tibet in the years 775 to 779 AD with the assistance of Padmasambhava himself – otherwise known, of course, as ‘Guru Rinpoche’ – the archetype of the ‘Precious Master’ who was the source of many lineages of teaching and practice.

My hope – my playful hope – is that looking at the sequence of images included with this article will, however briefly, give you the feeling that you were there at Samye in 1987 along with Norbu Rinpoche and that – if you do experience that feeling – it will give you a renewed sense of your deep, sacred connection to Norbu Rinpoche and to his other students, whoever they may be and wherever they may be around the world, and that, in this way, the Mudra of Samaya in your own life will be renewed.

John Shane

***

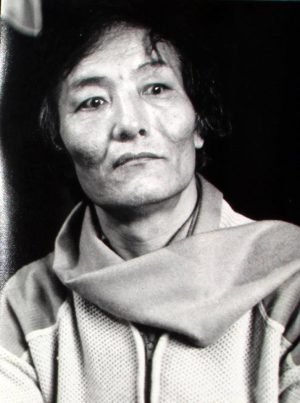

As a young man, Norbu Rinpoche had a hard choice to make. If he wanted to fulfil his commitment to serve all sentiment beings, he knew he would have to leave his family and his native country. He traveled alone to the other side of the world carrying nothing with him but the teachings in his heart and mind.

When he arrived in the West, at first he became a Professor at the Oriental Institute of the University of Naples. Later, after many requests, he began to give Dzogchen teachings.

When he arrived in the West, at first he became a Professor at the Oriental Institute of the University of Naples. Later, after many requests, he began to give Dzogchen teachings.

When I met Norbu Rinpoche in London in 1978, he was still a young man, and he had learned Italian, rather than English, so he was teaching in that language. Since I knew Italian, already had a grounding in Buddhist teachings, and had followed other Tibetan Buddhist masters, not long after meeting Rinpoche, I began to translate for him at his talks and retreats in different parts of the world, and later began to work on producing books in English with him.

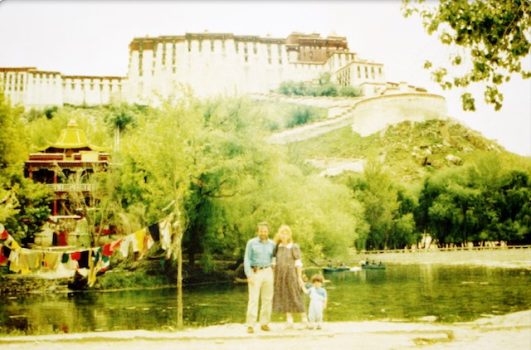

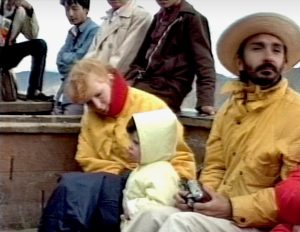

In 1987, while on a journey with Norbu Rinpoche that took us to many different countries, I traveled to Tibet along with Jo, who was then my wife, and our daughter Jessie – who was then 20 months old – and a very small group of Rinpoche’s other students.

When we arrived in Lhasa, Rinpoche stayed at his sisters’ small house on the edge of the town, while everyone else in our party stayed in hotels.

During our stay in Lhasa, among many other places, we visited the Lhukhang, the Dalai Lama’s Secret Temple that is situated on an island in a lake behind the Potala Palace, which can be seen in the photo above.

In order to be able to travel to sacred sites outside Lhasa, we hired a small bus with a local Tibetan driver. Donatella Rossi, an Italian student of Rinpoche’s, who spoke fluent Chinese as well as having a good knowledge of Tibetan, acted as our translator with our driver and any officials with whom we needed to interact.

When Norbu Rinpoche decided to visit Samye monastery, the first Buddhist temple to be built in his native country, we set out early in the morning in our bus, driving South East along rough roads for two and half hours to get there.

When we came to the Yarlung Tsangpo river, also known as the Brahmaputra, the river at the highest altitude in the world, we had to wait for the ferry to arrive, but, with the telephoto lens of my camera, I could see the ferryman in the distance, silhouetted against the sky as he approached us where we waited on the South bank of the river.

When the ferry pulled into the shore, we began to load our bags on board.

Most great lamas would travel accompanied by a retinue of monks… but Norbu Rinpoche never became a monk. After arriving in the West, he married and started a family, and many of his students, like myself, also had families. So, when I traveled with Rinpoche, it was accepted as completely normal that my family would accompany us, and that’s how my daughter Jessie came to travel to Tibet when she was still only twenty months old. Jessie never had any health problems at all on the journey around the world with Rinpoche. In fact, in Tibet, she was the only one of our party who didn’t suffer from altitude sickness when we first arrived, while even Rinpoche, who was born in Tibet, did at first have problems breathing at that high altitude, particularly at night.

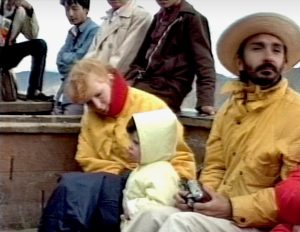

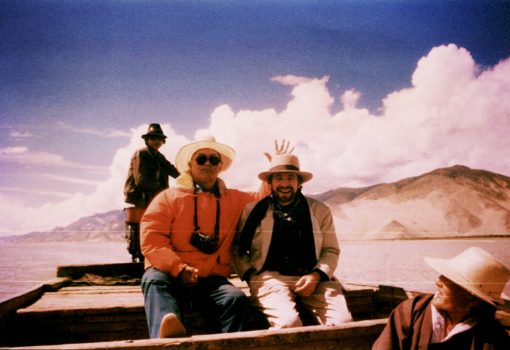

For part of the river crossing, I sat next to Norbu Rinpoche – as always joking, and ever playful!! – on board the ferry. Rinpoche’s elder sister, Asö, who lived in Lhasa, can be seen at the bottom right hand corner of the photo above.

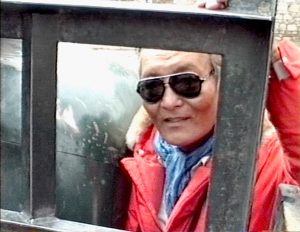

All through our trip, Rinpoche wore, as he often did, even in hot summer weather, a thick down jacket. On this trip, his jacket was bright red in color.

Phuntsog Wangmo, Norbu’s sister’s daughter, who is now the head of the Shang Shung Institute School of Tibetan Medicine, was at that time completing her studies in Tibetan medicine in Lhasa, and she was one of the small group traveling around the Lhasa valley with Rinpoche.

As we crossed the Yarlong Tsangpo a strong wind arose and we all had to bundle up against the cold.

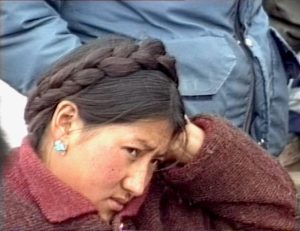

Phuntsog resting on the ferry.

Among the small group of Norbu Rinpoche’s close students accompanying him on the visit to Tibet, was Adriano Clemente, one of the principal translators from Tibetan of Norbu Rinpoche’s written works, who – fine musician that he is – also now serves as the Umze or principal chant leader of the Dzogchen Community.

As we approached the North shore of the river, we could see the old battered truck that was waiting for us – our ‘taxi’ that would take us to Samye.

It was hard to get the ferry close enough to the shore for us to be able to disembark, but finally, the ferry was close enough for Norbu Rinpoche, in his red down jacket, to be helped ashore, followed by his sister.Once we were all ashore, our baggage was loaded onto the truck, and we all climbed aboard.

As we set off down the bumpy track towards Samye, Norbu Rinpoche, and his sister rode inside in the closed cab of the truck, while the rest of us rode behind them, holding on for dear life up on the truck’s open flat bed with the cold wind blowing in our hair. When we arrived at Samye, Norbu Rinpoche’s sister descended from the cab, carrying his white straw hat.

Then Norbu Rinpoche himself, in his red down jacket, climbed out of the cab after her.

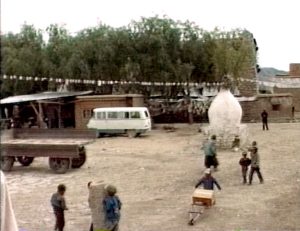

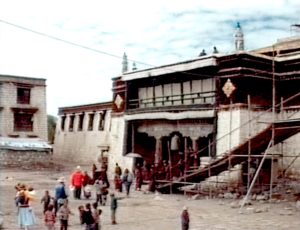

After the wild ride from the ferry in the truck, our small group of travelers assembled in the courtyard of Samye monastery, and, looking around the monastery courtyard, I could see some of the activities of the everyday life of the local people in progress.

As I looked at the damage that had been done to Samye monastery and filmed the ramps that had been put in place to enable repairs to be carried out to the once golden roof that had been completely destroyed, I remembered the words that Norbu Rinpoche had often said when I was translating for him:

‘In Tibet they built great temples and the temples had roofs of gold, but when the time came that we lost our country, did the temples with roofs of gold save the teachings…?

No. It was those who carried the teachings in their hearts and minds that saved the teaching.’

And, looking at Norbu Rinpoche in the courtyard of Samye monastery the ancient golden roof of which had been completely destroyed, I couldn’t help but think that he was himself someone who ‘had the teaching in his heart and mind’, so that when he had to leave his country he had carried the teachings with him wherever he went.

And, now that he had returned to Tibet, he was carrying those teachings back to their source.

Due to government restrictions, there were no grand lamas resident at Samye when we visited the monastery, but a welcoming group of young monks had gathered near the entrance doors as we approached.

At the main entrance of the temple, Norbu Rinpoche stood for a moment in silence looking up at where the destroyed roof of the temple would once have been.

I climbed up onto the roof of a secondary building to record the video from which this screenshot is taken, and from there I could see Rinpoche, in his white hat and red jacket, gazing up at the missing area of roof beyond the builders’ scaffolding.

Norbu Rinpoche led us to look at a column on which an inscription told the story of the founding of Samye and explained the meaning of the inscription.

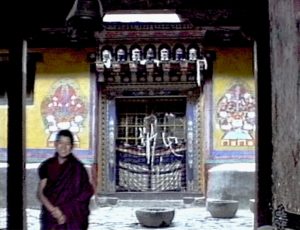

Then Rinpoche walked in through the main doors to a hallway where a senior monk was waiting to greet him.

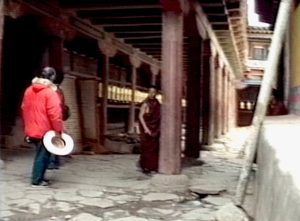

The monk led Norbu Rinpoche around the inner courtyard of the temple towards the centre of the Samye mandala.

Many artworks that had been painted as murals on the walls had been badly damaged, but where enough of the murals remained for us to be able to view them, Norbu Rinpoche explained their meaning to us.

The senior monk brought Norbu Rinpoche a stick wrapped in a white scarf as a sign of its sacredness.

‘This is the stick of Vimilamitra,’ Norbu Rinpoche explained, before telling us about the life of the 8th Century Dzogchen master, a disciple of Sri Singha and one of the eight teachers of Padmasambhava, who was invited to Tibet by King Trison Detsen and then stayed in Tibet for 13 years. It is said that he translated sutras and tantras by day while teaching at night giving Dzogchen teachings to the King and other students. Vimilamitra later left Tibet and went to Wu Tai Shan, where it is said he manifested the highest realization of Dzogchen, The Great Transference. Constance Wilkinson, a distinguished translator of Tibetan texts, listens to Rinpoche’s explanation together with Jo and Jessie Shane.

We were led up a flight of stairs to an upper level from where we could see out across the whole valley in which Samye monastery complex is located.

Norbu Rinpoche took advantage of being high up to take some photos of the layout of the monastery which was designed, based on the Buddhist temple Odantapuri at Bihar in India, as a mandala of structures representing the ancient Buddhist conception of the universe, with the main temple, the Utse, representing Mount Meru at the centre of the mandala.

We were then led back down to the ground floor again, and, as we walked with Norbu Rinpoche through the shadowy corridors leading to the central part of the temple, butter lamps burned amid the ritual tormas on an altar, and the corridors reverberated with the loud, insistent sound of a drum as a monk performed a ritual.

In a dimly lit corner, a different kind of welcoming committee waited for us. As the drum’s beat echoed off the temple’s walls, a mysterious Guardian statue stood shrouded in white scarves.

Norbu Rinpoche paid homage to the Guardian…

We walked on, past more butter lamps and prayer wheels…

…until finally we entered the central hall of the temple, where we could see, across the room, a statue…

… of Guru Rinpoche himself, the archetype of the Precious Master and one of the founders of Samye, who, through the power of his tantric practice, overcame negative forces that were preventing the completion of the building of the monastery, an activity that is re-enacted in the ritual performance of sacred dances.

Our Precious Master, Norbu Rinpoche sat for a few minutes on a bench among stacks of Tibetan sacred texts in their wooden boxes…

… as he gazed at the figure of Guru Rinpoche…

… then Norbu Rinpoche stood up and placed his head on the feet of the statue, bowing in homage to Guru Rinpoche…

The statue’s eyes, open wide, as in the practice of Dzogchen contemplation, met our gaze as we watched Norbu Rinpoche.

The Vajra, or Dorje, in Guru Rinpoche’s hand, symbol of the power and energy of the liberated mind, manifesting beyond place and time, points us away from Samye…points us away from Tibet…

…to another place, another time…to the founding of another temple, this one in Tuscany, Italy, in the late 20th Century.

As someone who carried the teachings in himself and embodied the essence of the teachings, manifesting Guru Rinpoche in his own life, Norbu Rinpoche brought the teachings with him from Ti- bet when he came to the West.

And on Monte Amiata, deep in rural Tuscany, in Italy, while I filmed him with my video camera, he placed relics he had brought from Tibet in the foundations of the first temple of the Dzogchen Community, a temple that he himself designed and for which he raised the funds, mirroring, the founding of Samye in Tibet so many centuries before, and maintaining the Mudra of Samaya that he manifested in his whole life.

Inspired by the example of Norbu Rinpoche’s life of service to others, I wrote this poem of aspiration in which I make a commitment to continue to carry out – to the best of my ability – my vocation as a poet and practitioner in the face of the many difficulties that we are all encountering in the world today.

Mudra of Samaya

(Lone Voice Crying In The Wilderness)

John Shane

Deep and ancient wounds

of colonisation and slavery

scar our nation’s history

and I cannot hope

to heal them all

Yet I swear

I will make

my contribution

no matter that it might

be small

I will raise my hands to work for

the common good

– I will raise my voice

to sing

And though mine may be

a lone voice

Crying in the

Wilderness

Still I will offer up my song

– for whatever blessings

it might bring

There is so much wealth

in this land

But it is held

in too few

people’s hands

To the poverty of the many

there seems to

be no end

And I have seen

the hunger

in their children’s eyes

turn brother against brother

and friend against friend

But I swear

that we can find

another way

to solve the problems

we all face today

And I believe in my heart

that I, myself, can change

so that, together

we can start

to end the conflicts

that are tearing us apart

I will raise my hands

to work for the common good

– I will raise my voice

to sing

And though mine may be

a lone voice

Crying in the

Wilderness

Still I will offer up my song

– for whatever blessings

it might bring

Some say that for those

like you and me

there can be no

salvation

They say that we have brought

our misery down upon ourselves

And that we are the cause

of our own downfall and

damnation

But what I say is that those words

are the lies

Of those who would not have us

even dare to try

to change our nation’s present

situation

Their words are like

poison in our ears

that serve no purpose

but to add to our fears

and I will not listen to them

I will raise my hands to work

for the common good

– I will raise my voice

to sing

And though mine may be

a lone voice

Crying in the

Wilderness

Still I will offer up my song

– for whatever blessings

it might bring

So many here stare

poverty in the face

and must do their best

with little more than

the bread of their

affliction

Too many streets in our towns

are filled with those who

have lost their homes

as they struggle in this world

– their lives ground down by

unrelenting poverty

that has led them to seek

false refuge in the oblivion

of addiction

I know there is no easy way

to get from where we are today

to where we need to be

But still I pledge my heart and soul

to the journey towards our destiny

And even though I know our final

goal

may be something I myself may not

be blessed

to live long enough to see

I will raise my hands to work

for the common good

– I will raise my voice

to sing

And though mine may be

a lone voice

Crying in the

Wilderness

Still I will offer up my song

– for whatever blessings

it might bring