Listen to This Article

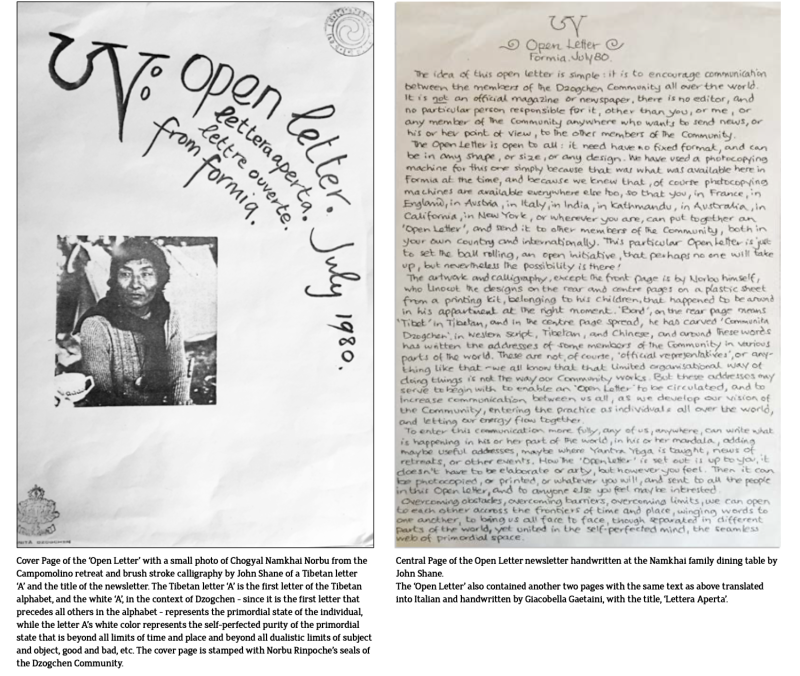

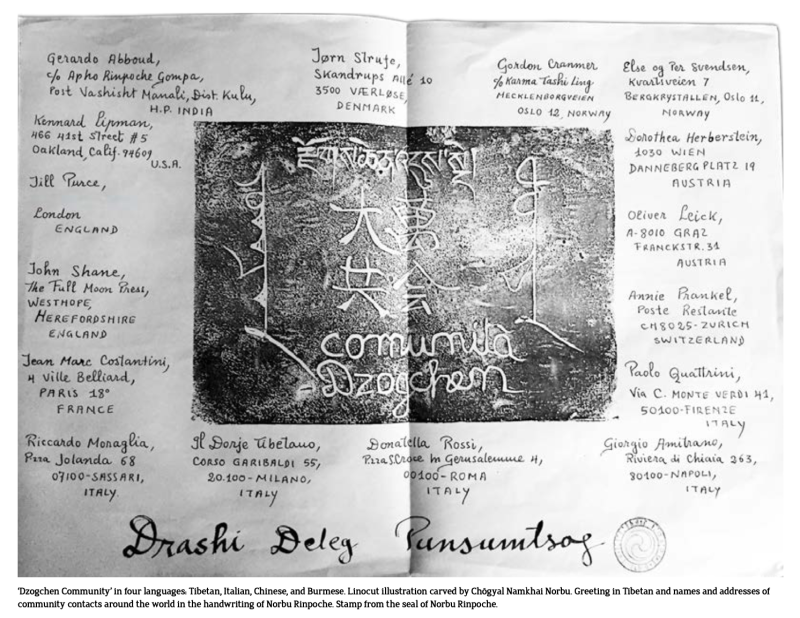

The first ever International newsletter of The Dzogchen Community, sent out from the Namkhai family apartment by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu and John Shane in July 1980 with artwork created by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu using his ten year old son Yeshi’s linocut printing set.

John Shane

Text and images © John Shane

In the early years of Chogyal Namkhai Norbu’s teaching, he didn’t like to go to any kind of Dharma center, so when the Community wanted to hold a retreat a suitable place would need to be chosen to hold it. Sometimes retreats were held in tents, but sometimes a hotel or even a whole resort complex was rented for the duration of the retreat.

In the early years of Chogyal Namkhai Norbu’s teaching, he didn’t like to go to any kind of Dharma center, so when the Community wanted to hold a retreat a suitable place would need to be chosen to hold it. Sometimes retreats were held in tents, but sometimes a hotel or even a whole resort complex was rented for the duration of the retreat.

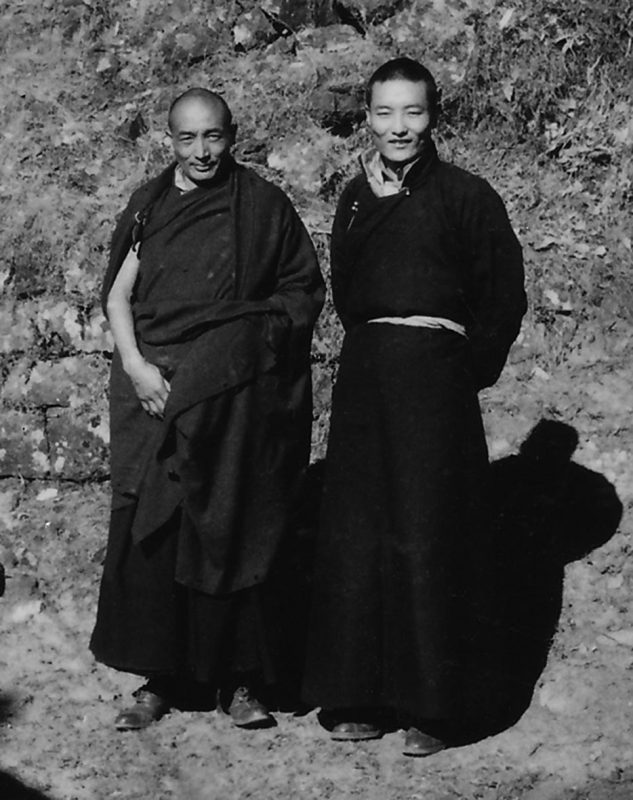

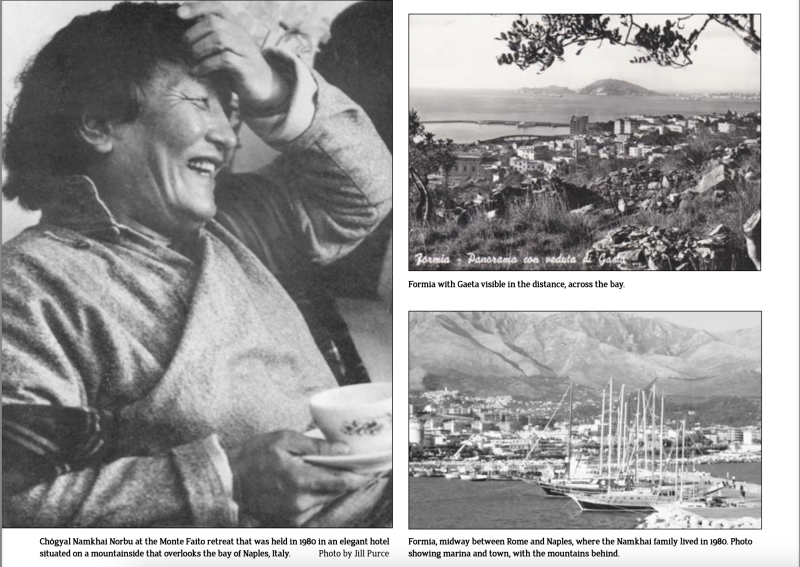

In 1980 a retreat was held in the elegant Grand Hotel Monte Faito, located on a mountainside overlooking the Bay of Naples, Italy, with Vesuvius visible in the distance the other side of the bay.

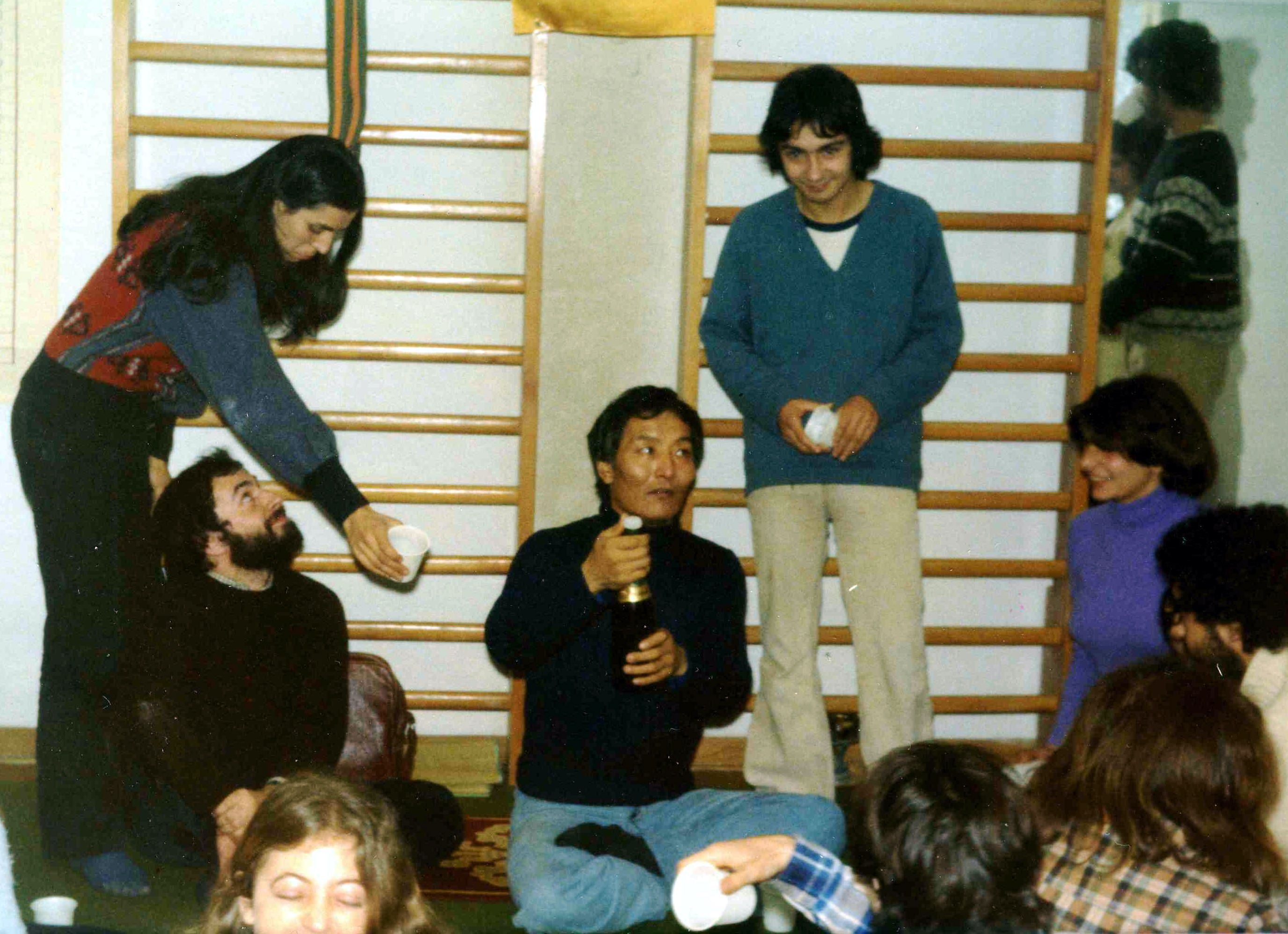

Those attending the retreat booked their own rooms, meals were taken in the dining room with waiters in crisp white linen jackets serving us, and the teachings were given in the ballroom. There was even a disco in the basement. This was certainly a different kind of location to any other retreat I had ever attended with my other Buddhist teachers, where everything had been more austere.

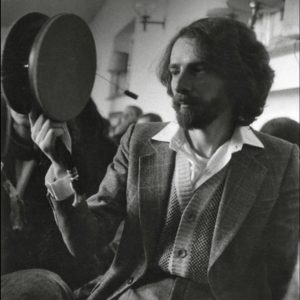

John Shane at the Monte Faito retreat.

During the retreat, as I stood one afternoon with Norbu Rinpoche looking out over the sunny garden, he turned to me and said, ‘John, John…!! Do you see the Dakinis dancing..!!’

When I asked where they were, he laughed and pointed in the direction of the tall pine trees waving in the wind the other side of the manicured lawns, and said, ‘There..!! There…!! Don’t you see them..!!’

He continued laughing, making a big display of being surprised when I told him that all I could see was the trees.

He was always full of fun and liked to joke with me and his other students, so I couldn’t tell if he was simply comparing the movement of the trees to dancing Dakinis or if he was telling me that there were actually Dakinis there that I should be able to see if I had the clarity to see them, but the whole conversation was very light-hearted, so I didn’t feel too much of an idiot about not being able to tell what he meant.

But then he suddenly became serious, and looking me squarely in the eyes, he said, ‘At the end of the retreat, why don’t you come and visit me for a few days at my apartment in Formia?’

This was the last thing I was expecting, and I thanked him profusely, accepting his invitation, after which he said he would tell me after the retreat finished how to get to his home.

When some days later I arrived by train at the railway station in Formia, I was even more surprised to find Rinpoche himself waiting for me with his car, an old Citroen DS.

As he drove me across the town, Rinpoche told me that I would be sleeping on the couch in the living room of the family apartment and that he would himself cooking a Tibetan speciality for dinner that evening.

I had no idea why he had invited me to stay, but I felt really honored that he had, and the whole Namkhai family made me feel really welcome.

Invited for a weekend, I ended up staying there for six months sleeping on that sofa in the living room, and it was during that time that I began to work on creating with Rinpoche the book that became ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light: Sutra, Tantra, And Dzogchen’, which many people consider to have been the first book to introduce the Dzogchen teachings to a wide Western audience and was certainly the first book to introduce to the world the story of Norbu Rinpoche’s early life and education in Tibet.

It’s important to remember that before Norbu Rinpoche began to teach, Dzogchen was not taught openly, particularly, to Westerners, but was kept as a reserved and secret teaching, and it was Norbu Rinpoche who opened to the door that gave access to authentic Dzogchen teachings to the wider world.

So the first book of his teachings to be published was very important in that regard. It not only brought many students to Norbu Rinpoche. It also provided an example of how authentic Dzogchen teachings could be presented, outside the context of Buddhist monastic institutions, to what we could call ‘ordinary people’ in the West.

I wondered later, if – since Rinpoche already knew that I could write and taught creative writing – he had invited me to stay for the weekend as a way to open the possibility that I would work on a book with him, but there was never any indication at the time that that was what was in his mind.

Anyway, whatever his intention in inviting me to visit his home, the work on ‘The Crystal’ began while I was there, but, as it turned out, it was to take four years of listening to dozens of hours of audio tapes of talks and reading every transcript of every teaching he had ever given to that date, and then continually rewriting the manuscript over and over again before I got the book into the form in which it was finally published.

The full story of what happened as ‘The Crystal’ was written will have to wait for another time, but another publication that can be considered a ‘first’ was launched while I was actually staying with Rinpoche and his family at their apartment in Formia: the the first ever international newsletter of the Dzogchen Community, to which we gave the title ‘Open Letter’, a title accompanied by a Tibetan letter ‘Ah’, representing the primordial state of Dzogchen, that one could describe as a state of total, complete openness.

Remember that this newsletter was sent out at a time when the internet had not even been thought of and there were no mobile phones or desktop computers in every home.

International communication at that time was only possible by sending letters through the post or by using a landline phone to make an expensive call.

When we decided that it was time to try to put people in the Community that was beginning to form around the world in touch with each other by mailing out a newsletter, I sat at the Namkhai family dining table with Rinpoche while we worked out what we wanted it to say, and then I wrote out by hand what we had decided on.

After that, Rinpoche went to look for a linocut printing set belonging to his son Yeshi, and, using the cutting tool, he carefully carved the illustrations for the newsletter into several rectangular pieces of brown linoleum, gently blowing away the little curls of lino that the cutting tool dug out.

Then, while Rinpoche’s wife Rosa, and his son and daughter Yeshi, Yuchen and I watched, Rinpoche squeezed black ink out of its silver metallic tube, spreading it onto a wooden board, after which he ran the roller over the board to pick up the ink and, one by one, coated the ink onto the rectangles of lino into which he had carved the letters and images he had imagined as illustrations for the newsletter.

When the ink was fully spread, he laid out some sheets of white paper and, again – one by one – he slowly pressed each rectangle of lino down onto one of the sheets of paper.

Tibetan scene with a yogi in a cave, a yak, birds flying over a temple, a stupa, with juniper smoke emanating from a serkang. Tibetan writing of the name of the country of Tibet, and its equivalent pronunciation indicated in Norbu Rinpoche’s Western transcription system as ‘Bond’. Lino cut by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. Illustration carved by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu using his ten year old son Yeshi’s linocut printing set.

As Rinpoche tentatively lifted each of the rectangles of lino off the paper, the Namkhai family and I all clapped our hands and cheered, laughing with delight as we saw the prints of the images he had created emerge in the black ink he had clearly stamped onto the white paper.

After the ink had fully dried, we put the pages of the newsletter together and the next day, while Yeshi and Yuchen were at school, Rinpoche and I walked across the town to the local photocopy shop where we made several dozen copies of the ‘Open Letter’ to send out by mail to community members all over the world in envelopes on which we would laboriously write out the names and addresses of the Community members.

As the wording of the content of the ‘Open Letter’ reflects, at that time, Rinpoche was not in favor of forming centers or of creating an organization.

In fact, he often used to say that organization was contrary to the teachings, and this view of his is not only reflected in the text of the ‘Open Letter’, but can also been seen reflected even more clearly in other documents remaining from that time, such as the brochures that were prepared and circulated to announce upcoming retreats, copies of which I still have in my archive.

Other than permitting a small number of those printed brochures, Rinpoche would not in those days allow any advertising of any kind for his teachings or retreats, saying that advertising conditioned people and the Dzogchen teachings exist to free people from all conditioning.

He said that people had to have a deep cause, not a superficial cause created by publicity, to come into contact with his teachings.

He also use to say that the point of the teachings was to help one go beyond all limits.

‘Awareness is the only rule in Dzogchen,’ he world say. ‘You have to come out of all the cages with which society has imprisoned you and in which you have closed yourself up.’

His aim was to teach the essence of the Dzogchen teachings, the essence of Tibetan Dharma, and the free-form structureless idea of how the Community should be at that time was in harmony with that aim.

Later, of course, as he always said he would do, he worked with circumstances to adapt to the changing conditions that arose as the Community developed and grew in size after his books and his continual travels around the world to give teachings began to attract more and more students.

But it seems clear to me that he didn’t want to permit any structure or any organization to be formed around him or any centers to be formed by his Community until he was confident that he had enough students who had fully understood that all those material aspects that can surround the teachings themselves – the structure, the organization, and the centers – are not the principal things.

It was only some years after the ‘Open Letter’ had gone out, only after Rinpoche had made it clear to his students that the teachings are essentially not about structure and centers that he began to consider founding a centre.

And even then, it is significant that he used the name ‘Gar’ to define his centers, ‘Gar’ being, of course, the Tibetan term for a temporary encampment of nomads rather than a permanently fixed place.

This choice of a name was intended to remind everyone of what he said so often in the days when he would neither teach in centers of other Dharma groups or allow any centers to be founded in his name:

‘The true center is the individual,’ he would say, ‘but don’t interpret those words in an egocentric way. What I mean is that, in Dzogchen, the individual’s own primordial state is the true center, the true center of the universe. Everything else arises from that center as the play of the energy of the primordial state’.

I will be writing more stories of my travels and work with Rinpoche, and it’s my hope that ‘The Mirror’ – of which I was a founding editor – will be able to publish some of them.

But I have a lot of stories to tell, and, as I’m getting old, there is less time left for me to tell them than there once was. So I’m planning to revive the ‘Open Letter’ as a place online for me to publish my stories and to post podcasts of them for those who sign up to read or listen to them. ‘Watch this space..!!’, as the saying goes….

John Shane is a poet, author, musician, and teacher of Creative Writing and during the years that Norbu Rinpoche gave teachings speaking in Italian, he often translated Rinpoche’s teachings into English at many retreats in Italy and other parts of the world. John also worked closely for four years with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu writing ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light: Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen’ for him, as well as translating from Italian into English a number of his other books, including ‘Dzogchen: The Self-Perfected State’. Later, John was a founding editor of ‘The Mirror’ newspaper. He currently divides his time between working at his studio in England, where his family resides, and doing personal retreats at his old farmhouse in Tuscany near Merigar.

In those pre-internet, pre-home computer, pre-cellular phone days – long before Merigar was even thought of – when he was at his home, Norbu Rinpoche used to receive phone calls almost every day that came in from all over the world on a beige bakelite Telecom Italia telephone that was plugged into the wall of the Namkhai family living room with a long black curly wire.

When the phone rang and Rinpoche picked up the receiver, he would often find himself speaking to someone who had either themselves just been given a diagnosis of some kind of serious illness or who had had some accident, or who wanted to talk to him about some other person – perhaps a loved one – who was caught up in a drama of physical or mental suffering of one kind or another.

Listening to Rinpoche respond to these frequent calls asking for his help and hearing the advice he gave as he answered the calls, I came to realize for the first time the weight of the responsibility he carried as a result of his having accepted the role of becoming the spiritual teacher of so many people.

I didn’t, of course, have the same kind of responsibilities Rinpoche had, but while I was staying with the Namkhai family in Formia I received a letter from a friend who led a Buddhist group back in England who was suffering from a serious illness, and inspired by the example of Rinpoche’s compassionate responses to the people who phoned him, in my reply to my friend’s letter, I wrote this poem:

For Mala Young

a Dharma sister dying of cancer

15th. May, 1980. Formia, Italy.

(Written at the private apartment of the Dzogchen Master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, whilst staying there as a guest.)John Shane

Bodies are failing things, Mala,

always overcome by time,

and yet body, form and matter

are but grosser forms of mind.Freedom is hard fought for

and hard won.

The truth is often bitter,

answers often paradoxes,

questions seldom one.Surrendering seems easy

as long as we can

hold a little something back;

the body is a vehicle,

yet when it gets weak,

our fear makes our vision black.Death and darkness

are not easy things to face.

Each stands alone,

in this there’s nothing new.

Yet each, alone, is also

fully part of all around;

Mala, none of this

is news to you.Searching for

an independent self,

none can be found;

all is impermanent,

all interpenetrating;

mind is essentially free

only our conditioning

ties us down,

preventing us from being

all that we could be.But these are only words,

each one of them a liar,

these are only words

and your pain is like a fire.Yes, it burns, but its burning

is like a purifying flame.

There is no need for

any sense of guilt,

there is no blame.Your cancer is not

a cause for shame.Fire, needing

darkness

to show light,

flows upwards

in the river

of the night.Brave sister,

proud lioness,

defender of the dharma,

in the dancing dream of life

your song is singing true

even though, at times,

your sickness

may seem to be undoing you.Unfolding itself and

folding itself

at the same time,

in-breath and out-breath,

weaves the way,

between life and death.We’re always afraid of

the unknown somehow

but there’s nowhere to go, Mala,

because it’s always

here and now;and I wanted to send you my love

and sympathy of angels

and, of course, words won’t do,

but words are all I have to send,

and so I send them to you.

You can also read this article in:

Italian