Chögyal Namkhai Norbu

In an exclusive interview broadcast in Tibetan on August 6, 2014 with Kunleng VOA Radio station in the USA, Chögyal Namkai Norbu, Head of the International Shang Shung Institute, discusses his research work on the origin of the Tibetan script, the impact of Shang Shung on the Tibetan culture, and his books regarding the Bön tradition and Dzogchen practice.

Kunleng: The great scholar, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, while residing in the West over many years has worked in connection with the Tibetan culture and religion and has written several books on [the ancient kingdom of] Shang Shung as the origin of Tibetan language, script and culture, and on the practice of Dzogchen. These days Rinpoche is in New York to attend a conference on Tibetan Medicine and the Kunleng office has taken the opportunity to specifically invite him for this interview.

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, first of all we would like to welcome and thank you very much for having come today to the Kunleng office of the Voice of America Tibetan News here in New York.

Rinpoche: Thank you.

Kunleng: Rinpoche, what is the main reason for your visit to New York?

Rinpoche: I came here mainly for two purposes – to attend a conference on Tibetan medicine organized by the American Tibetan Medical Association, the International Shang Shung Institute and the Shang Shung School of Tibetan Medicine, and also to participate in the inauguration of a new building the Dzogchen Community has recently constructed.

Kunleng: So one of the main purposes of your visit is to participate in a conference on Tibetan medicine. Tibetan medicine has a very long history. What is the situation of Tibetan medicine today, and why it is important to preserve and ensure its continuation?

Rinpoche: In the Tibetan culture there is not only Tibetan medicine but the so-called five traditional sciences [language, dialectics, medicine, arts and crafts, and spiritual knowledge]. These five sciences are the foundation of all Tibetan culture and are very ancient. I did research for many years [on their origin] when I was working at the University in Italy. In particular I wrote three books [i.e. The Light of Kailash] of which the first two have already been translated and published in English. The third will be published at the end of this year. In these books I explain not only [the ancient origin of] the language but also that of the other four sciences – logic, spiritual knowledge, medicine, arts and crafts. Among these the most important is spiritual knowledge.

Later, however, language, and Tibetan medicine came to be regarded as the most important aspects of Tibetan culture, while spiritual knowledge was not considered as such. When I did research on these traditional sciences I discovered that they had an ancient history and were not just sciences imported from India and China that spread later on. I did research on this for about six or seven years.

This is an important matter which Tibetans living inside Tibet as well as those living abroad should take interest in. This is because our ancient culture is of benefit to all people, all races of the world, not only Tibetans. This is true for Tibetan medicine as well. Tibetan medicine has its origin in the medical tradition of Shang Shung, which has an ancient history. In the documents discovered at Dun Huang there are two texts of Tibetan medicine: one deals with the treatment of illnesses, and the other with moxibustion or Metsa. In the [colophon of the text] on moxibustion, it is written that it came from Shang Shung, hence it is important that doctors and people of culture understand that [Shang Shung] is the foundation [of the Tibetan culture].

Kunleng: Rinpoche, you have taken great interest and have done a lot of research into the history of Tibetan culture and civilization. What is the particular reason for such interest?

Rinpoche: The main reason for my interest is the following one. When I first worked at the University in Italy, the subject I taught was the Tibetan language and writing. The Tibetan language course consisted of only two years [of study], while the other language courses such as Indian, Chinese and Japanese were of four years, at the end of which students could receive a diploma. But it was not so for Tibetan language. So I inquired at the university why the studies of Tibetan language there were only two years. They replied that the languages like Indian and Chinese that had an ancient history were the main subjects of studies and were awarded with diplomas, but since the Tibetan language did not have a ancient history it was considered only a supplementary topic of study, not a main one. I had no opportunity to say that that was not the case and that we Tibetans had a long history. I knew that Tibetan culture had an ancient origin and understood that I had to research such an ancient source; that is how I began my studies on the history of Shang Shung.

Kunleng: Rinpoche, a year ago, in an interview you said: “The source of Tibetan culture and Tibetan history should be searched for in Tibet itself. It is a great loss if we assert a source of culture and history that just follows what other people say. With great courage, taking real history as the base, I composed the Necklace of Zi and the Necklace of Jewels in which I prove through logic and reasoning that the early ancient authentic history of Tibet came from Tibet itself or Shang Shung.” So more than thirty years ago you wrote the Necklace of Jewels in Tibetan, and after that the Necklace of Zi Jewels. Why did you write these two books? For the reason I have just mentioned [from your own words] or for the new generations so that they understand the source of Tibetan culture?

Rinpoche: In general, most Tibetan scholars consider India to be the source of the Tibetan culture and indeed it is true that India is one of the sources. Buddhism came from India, and as the result of its introduction into the country many aspects of the Tibetan culture underwent great development. [On the other hand] it is not really correct to say that the foundation, the origin of the Tibetan culture was in Tibet itself because Tibet as a country did not come into existence [until later].

I have written three books related to Tibetan history [The Light of Kailash]. In the first book I deal with a period in which there was only Shang Shung [and Tibet did not exist as a country]. It is only in the second book that I begin to explain the establishment of Tibet as a country. Why must [the origin of the Tibetan culture of Tibet] be traced back to Shang Shung? The foundation of Tibetan history lies in the six original Tibetan clans [mi’u gdung drug] who are said to be the source of the Tibetan race. In Tibetan history it is said that these six clans came from a monkey, who was an emanation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and a rock Sinmo [brag srin mo]. But if we look at the ancient history of the Bönpos, it is said that the six original clans came from the cosmic egg that is the essence of the elements, and from that came the three: Lha, Lu [Klu], Nyen. Among these, the human race originated from the Nyen lineage, and in particular the six original Tibetan clans. Thus, the lineage of the six clans came about in that way.

This is very ancient history and before Tönpa Shenrab [the founder of Bön] there are only a few orally told histories, and no written history. At the time of Tönpa Shenrab the Shang Shung script called Martsug (smar tshugs) was created, and from then onwards, the knowledge [originating from] Shang Shung such as Bön, astrology, rituals, etc., were gradually written down. Thus ancient history was written down at the time of Shang Shung, not in the era of Tibet.

The era of Tibet is when Thonmi Sambhota created the script. It is usually said that Thonmi Sambhota created the Tibetan script taking as an example the Indian language. Thonmi Sambhota was very kind in creating the Tibetan script, however, before that, from the time of Nyatri Tsenpo up to Srongtsen Gampo, i.e., during the dynasties of thirty-one, or according to others, of thirty-two kings, however many kings there were, it is said that the country was ruled through Drung, Deu, and Bön, but it is not said that there was written language. However, later when I did some research I found a lot of evidence of the existence of a written language. [For example] in a history written by Nyang Tingdzing Zangpo, he says that the ancient Tibetan kings used a written language. Therefore, whichever way we think, [there must have existed a written language before the time of Thonmi Sambhota].

We have two kinds of Tibetan script: Uchen [headed letter] and Ume [letters without heads, i.e. cursive letters]. The Uchen script and its grammar were definitely created by Thonmi Sambhota on the basis of the Indian script, but the Ume script originates from the Shang Shung script, of which there are mainly two kinds: Marchen and Marchung. Among them, in particular, the Marchung corresponds to the so-called ‘Script Descended from the Devas [lha babs yi ge]’. I studied that script when I was in my native place, and used it as example in the Necklace of Zi. [The letters in] Uchen are written from right to left, and Ume from left to right. I see this as a great difference between the two scripts.

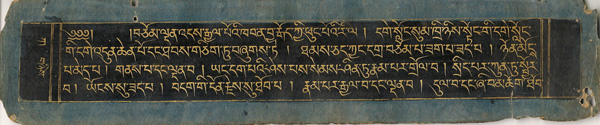

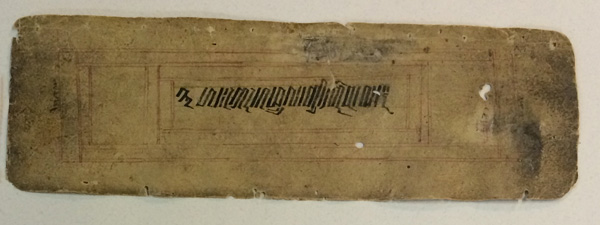

Ancient handwritten pecha with two different styles of Umed script. (Courtesy of the Merigar library)

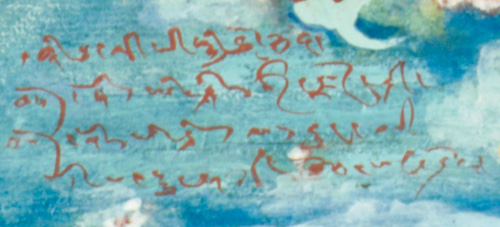

Ancient pecha in Lha-babs-kyi-yi-ge script, ‘descended from the gods’. (Courtesy of the Merigar library)

I generally have a great consideration for whatever Gendun Chöpel has taught, but I do not agree with him when he says that Ume developed from writing Uchen in a fast way. This is absolutely not the case. For example, there is the so-called “quick Bhutanese script” that certainly comes from writing the Uchen in a quick way. But this is not the case with Uchen and Ume – even if one writes Uchen in a quick way for centuries, it will never become Ume. The reason why Ume is quicker is that one starts to write [each letter] from left to right. Thus it is good if we consider the Shang Shung script as the origin of Ume.

Kunleng: Rinpoche, according to most of the explanations [we find in] Tibetan history and by Tibetan scholars, the Tibetan language was first created anew by Thonmi Sambhota. But in the Necklace of Zi, you say that the Tibetan script originated from the time of Shang Shung and thus it was used from ancient time. What are the Dung Huang document sources and the proofs for such a statement?

Rinpoche: One of the proofs is as follows. If we consider the Dag Yig or Sum rtags, the grammar and spelling composed by Thonmi Sambhota, there are but five genitives, while in the language of Shang Shung there are eleven genitives. If we look at the Dun Huang documents, at the time when Thonmi Sambhota had already composed his works, in some documents occasionally genitives still appear that were used in the language of Shang Shung. So this indicates that they existed from an earlier time.

Kunleng: Are you saying that Thonmi Sambhota made the Tibetan language simpler and easier to write, and composed new grammar texts, but apart from that writing existed prior to that time?

Rinpoche: The Tibetans used and were able to use the Shang Shung language. If we read attentively what Songtsen Gampo said: “We Tibetans, in Tibet, needs our own script.” He did not say that there was no written language and that they needed to create one. Why did he say: “Tibet needs its own language”? Because many earlier kings did not like and undermined the Bönpo, and they tried many times to make Tibet a strong country, for example, at the time of Drigum Tsenpo [gri gum btsan po, 8th dynasty], but did not succeed. Also during the reign of Tagri Nyenzig [stag ri gnyen gzigs, 21st dynasty] a similar attempt was made. Why they did not succeed? Because, at that time, the Tibetan culture and the rule of the kingdom all relied on Shang Shung sources, and for this reason Tibet was not able to become a strong country. The influential power of the Shang Shung culture extended over the Tibetan kings.

We can understand this if we look at the histories of these kings. The kings had two kushen [ku gzhen, Bönpo priests]. From the time of Nyatri Tsenpo until the last dynasty of the Tibetan kings, each Tibetan king had a Bönpo priest. The priests named the kings and even when Buddhism had spread and Guru Rinpoche and the other [masters] had come to Tibet, the Bönpo priests continued to name the kings. The Bönpo priests had two functions: one to name the king and the other to perform the ablution rituals [sku khrus] for the newborn king.

What was the reason for kings to have Kushen? When Buddhism began to spread in Tibet, [the kings taught that] if the ancient traditions [of the Bön] were discontinued, the Bönpos would have sent some curse, or there would have been some calamities, and for that reason they had Bönpo priests [at the court].

Therefore the Bönpo culture had a very strong foundation and the Tibetan kings, thinking that this prevented them from becoming powerful, tried to destroy the Bönpos in many ways. And it is for this reason that Srongtsen Gampo developed a new culture through relations with India and China, and favored the introduction of Buddhism, and in this way overcame Shang Shung.

Kunleng: Rinpoche, in your books you say that the source of the Tibetan culture is the kingdom of Shang Shung. However, nowadays all Tibetans consider and say that our culture and habits are very much connected to the Buddhist religion. When you say that the Tibetan culture has its source in Shang Shung, are you speaking of what nowadays we consider to be our present culture or something different?

Rinpoche: All the aspects of our present culture, even if they had their source in Shang Shung, have, of course, undergone some change and developed. Take for example medicine that originated in Shang Shung. Over many centuries [with the integration of medicines] from India, from China and also from other countries, Tibetan medicine developed a great deal. This did not occur only with regard to medicine; other aspects of our culture, too, developed in a similar way. Tibetan religion and culture developed, but apart from that there is no need to denigrate our existing ancient culture.

Kunleng: Whatever Tibetan culture we have now is the continuation of the culture of Shang Shung?

Rinpoche:The origin or primordial source of the Tibetan culture is Shang Shung. The language of Shang Shung had its own grammar, [for example] as I mentioned before, eleven genitives were used in the language of Shang Shung. Thonmi Sambhota simplified that grammar, by having only five genitives.

Kunleng:Rinpoche, you are a Buddhist practitioner and on the top of that, in particular, you are a Dzogchen practitioner. What is your particular reason for your interest in Dzogchen?

Rinpoche: The particular reason for my interest in Dzogchen is that I met my teacher, who was a Dzogchen master. Having received teaching from him, I came to understand that Dzogchen was the essence of all the sutras and tantras, of all the teaching of the Buddha. Dzogchen is not at all something that belongs to the Bön [tradition]. But when I was doing research on [ancient Tibetan] history I came to know that Dzogchen teaching existed in Bön. Therefore, there is the so-called Shang Shung Nyengyu that definitely has historical validity. In that [transmission] there is an explanation of Dzogchen in twelve [verses] that clearly present the view, the meditation, the conduct, and the result, each distinguished in three aspects. That teaching [in its present form] originated from the Bön teacher Nangsher Löpo, who was the teacher of King Ligmincha, the last king of Shang Shung.

Limincha was murdered during the lifetime of Srongtsen Gampo, who then overpowered the kingdom of Shang Shung. However, sometime later, Srongtsen Gampo fell ill. These events are recorded in the Dun Huang documents. Srongtsen Gampo had a nerve disease, and not one of the doctors was able to cure him. The Bönpos from Shang Shung told Srongtsen Gampo: “Your illness that none can cure was caused by a curse from Nangsher Löpo, the teacher of [king] Limincha whom you had killed. So nobody can cure you except him.” Thus Srongtsen Gampo sent his ministers to search for Nangsher Löpo. Once they found him they invited him [to Srongtsen Gampo’s court] where he performed a ritual and Srongtsen Gampo was cured from his illness.

After he recovered from the illness in thanks Srongtsen Gampo donated the land where [the monastery of] Meri in Tsang is now situated, where they could stay permanently. From that time onward, the Bönpos could dwell there and that is why we have the thankas of the ancient kings of Shang Shung, and the old things from Shang Shung. Bönpos residing in other places were sometimes expelled somewhere else.

Nangsher Löpo had that Dzogchen teaching, but no written Dzogchen text existed prior to him. There were only Nyengyu. Nowadays when teachers write some teachings they entitle all these Nyengyu [oral transmissions]. But in Dzogchen Neyngyu consists of just few words, which are not written down but spoken in the ear of the person. In periods of social unrest when texts and so forth were not allowed, these Nyengyu continued to exist.

In the very ancient texts of Dzogchen it is said that twelve teachers of Dzogchen have appeared, the last being Buddha Shakyamuni. Eleven teachers appeared before him in very ancient times. At the time of Garab Dorje nothing remained of what these eleven teachers had taught, not even a Dzogchen scripture existed. Only Nyengyu remained, and Garab taught them again. When we introduce the view of Dzogchen even nowadays these Nyengyu are taught.

Kunleng: In one of your books while discussing whether Dzogchen belongs to Bön or Nyingma you wrote that the practice of Dzogchen is not limited to the Bön or Nyingma but is found in all schools [of Tibetan Buddhism]. What is the reason for this statement?

Rinpoche: If we really study the principle of Dzogchen we understand that Dzogchen is not a spiritual tradition. Dzogchen is the ultimate state [of the individual], and as such it is the arrival point of all spiritual traditions such as the Nyingma, Kagyü, and Sakya. Apart from that there is no Dzogchen. But in our world we always label everything: “This is this, that is that.” We don’t set things together but distinguish them. Thus Dzogchen is the ultimate essence, the final goal, of all Buddhist traditions.

In Dzogchen [it is said that there were] the twelve [primordial] teachers of Dzogchen, the first of whom was called Tonpa Nangwa Tampa, who appeared in the age of perfection. The main tantra that he taught in that age of perfection is the root tantra of the Dra Thalgyur, the Dra Thalgyur tantra. That tantra it is still extant nowadays, but if we read it, it is not so easy to understand all its content. However, there is a commentary to that tantra written by Vimalamitra.

When I was living in Tibet I never saw that commentary, but when I went abroad I heard that there was an original copy of it in the library of the Fifth Dalai Lama in Drepung.

Twice [when I visited Tibet] I gave lectures to young Tibetan students of the College of Science [Tsanrig Khang] and became friends with them. They made an insistent request to the local authorities for permission to put the texts in order, and they received this permission and made a list of them which they sent to me. When I looked at the list I saw that there was a commentary to the Dra Thalgyur composed by Vimalamitra. I thought: “Oh this is amazing. I must get a copy of that text.”

I had some friends at the Science College and asked them to make a copy of that text and send it to me. But they told me that it was not possible to make copies, and that they would not get the permission to do so. I told them that I absolutely needed that copy, and to do whatever they could to get it. In the end they were able to make a copy and sent it to me. The text in the cursive script was difficult to read and had many mistakes. I worked for three years checking and correcting everything, and now I have it in my computer.

In the Nyingma system they speak of the nine spiritual vehicles. In general these vehicles are listed as the three of shravaka, pratyeka, bodhisattva, the three outer tantras of Kriya, Ubhaya and Yoga, and the three inner tantras Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga. However, in that tantra [the Dra Thalgyur] the nine vehicles are not listed in that way. Instead of being listed as the vehicles of shravaka, pratyeka and bodhisattva, the first three are as follows: the worldly vehicles of humans and gods; the vehicles of the shravaka and pratyeka, and the bodhisattva vehicle. The worldly vehicle of humans and gods includes all possible spiritual paths, and [that tantra says that] the very essence, the final destination of all these is Dzogchen. Therefore Dzogchen is the essence of all spiritual paths.

Kunleng: Nowadays what is the situation regarding the upholding, preservation and propagation of the Dzogchen teaching, inside and outside Tibet?

Rinpoche: Nowadays, in the area of Amdo there are many Lamas who are Dzogchen practitioners, and who have a very good education. Outside Tibet there are also many khenpos and lamas with experience and realization. Thus the condition of the Dzogchen teaching is excellent.

From my perspective, since Dzogchen is the essence of the spiritual teachings, in foreign countries, [I teach] that Dzogchen is the essence of all teaching to anyone who is interested in spiritual matters. The benefits of its practice are not limited to the spiritual field, but also extend to secular life in general.

Regarding the fundamental principle of the view and meditation, Dzogchen is known as the state that is free from limitations and partiality. In our world, leaving aside for the time being the spiritual field, let us take as an example secular life. Even in a single country there are always many social conflicts, and conflicts between parties and so forth. If we were to understand and have some experience of Dzogchen, we would be able to free our own minds, and if we could do that the benefits would reflect on the country, on the society itself. Thus [Dzogchen] would help everyone. I usually try to explain this to people as much as I can.

Kunleng: In the introduction to the Necklace of Zi you say: ”Whether Tibet and Tibetans will remain for long or not will depend on whether the Tibetan culture will remain for long or not. It will depend on how the Tibetan culture will stand by itself.” The society and the generations inside and outside Tibet are changing considerably. According to you, what is the condition of the culture and in particular the language nowadays, and what should we as Tibetans pay special attention to?

Rinpoche: My great hope, and a very important thing, is that people inside and outside Tibet – the scholars but also other people – should be able to show the dates of the very ancient origin of the Tibetan culture and history.

In the books on history that I wrote, I combined our calculations [of dates] based on the Mewa cycles of 60 [sme phreng] and 180 years [sme ‘khor] with the dynasties of the kings [rgyal rabs] and centuries [dus rabs]. According to these calculations, in this year, 3931 years have passed since the origin of the Tibetan culture. All Tibetans should research this, otherwise to those people who say that the history of Tibet is [only] 2000 years old, there will be no way but to [say] that it relied on India or China.

It is not like that. Almost 4000 years have passed since the beginning of the Tibetan culture. Thus people who understand that will think: “Ah, the Tibetan culture is very precious. We should take great interest in it.” I really hope that this will happen.

Kunleng: Whether one studies the [Tibetan] Buddhist teaching or does research into [Tibetan] history, one needs [knowledge] of the Tibetan language as the basis. Looking at the condition of Tibetan society nowadays, in your opinion, is what is being done nowadays with regard to the responsibility of preserving the Tibetan language sufficient or should something more be done, and if that is the case what should be done.

Rinpoche: It is almost two years now since I first heard some [modern] Tibetan songs while was staying on the island of Tenerife. One of these songs said: “With songs and melodies we make our feelings and our condition public,” and I thought: “Oh, I must listen a little to these songs.” Usually I never listen to Tibetan songs but from that time onward I have listened to these songs and their contents.

Many of these songs talk about the decline of the Tibetan language and writing in Tibet, and about it falling into disuse, and of many other sad situations. Thus, I thought that people – whether Tibetans or foreigners – ought to know about this situation.

In general, I am not interested and do not engage at all in politics, I only do cultural work, thus I thought that these songs were valuable. So now I listen to these songs, I transcribed them, had them translated, and ask my Western students to study and sing these songs. This is because I think it will greatly help the survival of the Tibetan culture, and in particular the language.

Kunleng: Rinpoche even though you have a tight schedule here New York, you had time to come to the Voice of America radio and we wish to thank you for giving us the possibility to organize this interview.

Rinpoche: Thank you. I am very happy. It was a good opportunity to talk together.

Kunleng: Thank you.

Translated from Tibetan by Elio Guarisco

Edited by L. Granger

The interview in Tibetan can be see at: http://www.voatibetanenglish.com/media/video/1972897.html