“The lineage of my Teacher Rigdzin Changchub Dorje (Byang chub rdo rje) goes directly to Guru Padmasambhava; there are no human masters in it because he is a great terton. One of the sons of the Tibetan king Trisong Detsen was called Muti Tsenpo. Changchub Dorje is considered to be something like a reincarnation of King Muti Tsenpo. Guru Padmasambhava transmitted this treasure teaching to him and kept it in the mind of Muti Tsenpo. Changchub Dorje woke up and he had that remembrance and he discovered that teaching. Guru Padmasambhava indicated that for the future Muti Tsenpo would appear again in the form of master Rigdzin Ösel Lingpa, this is one of the four or five different terton names of Master Changchub Dorje. A terton of ten has a particular name in relation to his termas. For example, Jigmed Lingpa is the terton name of Chentse Ösel.

“I now have all the series of terma of Changchub Dorje and also the root tantras. Many years ago I was very worried, thinking that maybe I wouldn’t be able to find all his books. In Tibet during the Cultural Revolution they were destroying everything, but the students of Changchub Dorje hid most of the books of his teachings in the rocks. Later when they had more freedom they took them out. When we had the possibility to have communication with Tibet, I wrote to my friends, students of my master Changchub Dorje, and they sent me most of the original books. Later, when I went to Khamdogar, I took all the other books. So now I have all the terma teachings of Changchub Dorje.”

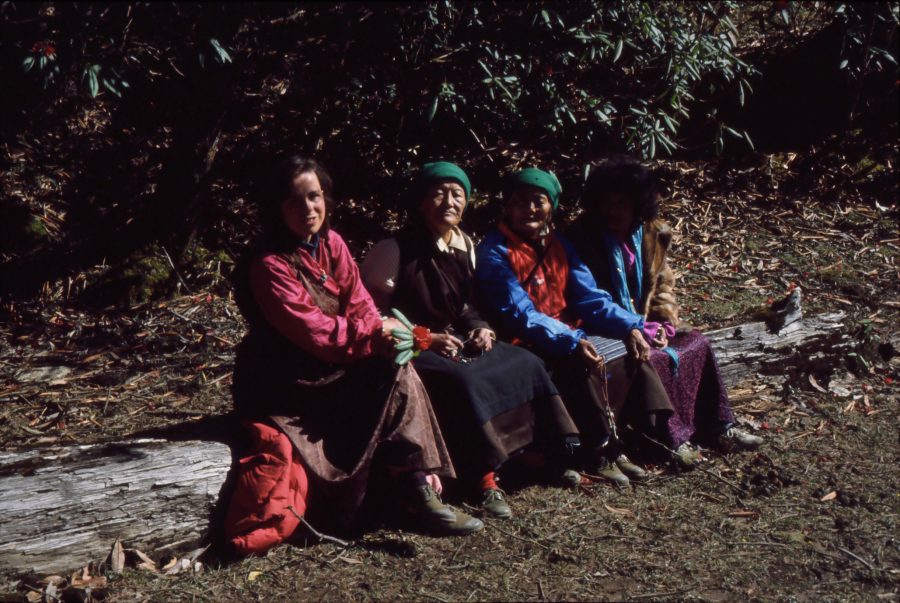

Rigdzin Changchub Dorje was a disciple of Adzam Drugpa, Nyagla Pema Düddul, Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen and Drubwang Shakya Shri, but he himself was not well known as a teacher. He didn’t give formal initiations or wear elegant robes. He dressed like a poor farmer and transmitted the teaching in a simple direct way. Very few people knew him as a great Master, but he was famous as an extraordinary doctor.

Although he had never received any formal education and could hardly read or write and had never studied traditional medicine, he was widely known as a marvellous doctor. Numerous patients travelled long distances to be treated by him. When Trogawa Rinpoche gave teachings on medicine in London in the early 1980s he said there are three levels of doctors: the highest level is the Buddha who gives the definitive cure; on the medium level there are those who never need to study because they are totally clairvoyant and know what is wrong with the patients and how to cure their diseases without even seeing them, and on the lower level are those who have to study for many years. He said he had only known one on the medium level and that was Rigdzin Changchub Dorje.

He was born in the village of Dhakhe in the Nyagrong (nyag rong) district in South-Eastern Kham. His mother, Bochung (bo chung), was originally from Dege and was a disciple of Gyalwa Changchub (rgyal ba byang chub), a highly realized yogi from Khrom. He founded his community of mostly lay practitioners in a remote valley in Konjo in eastern Dege. It was and is still to this day known as Nyaglagar and also as Khamdogar.

All those who lived there shared in the farming work, the gathering and preparation of medicinal herbs and the treatment of patients. They were each offered a bowl of simple soup every day. When the Chinese Communists arrived in the area in 1955, with the intention of implementing their agricultural reforms they were surprised to find that the Gar was already functioning as an agricultural commune and therefore was not in need of any reforms.

It was also in 1955 that Chögyal Namkhai Norbu met Rigdzin Changchub Dorje. He had dreamt of a place where there was a white house that had some mantras of Padmasambhava painted in gold on a blue board above the door. On the inner wall there was a thigle with A and there was an old man sitting in a corner. He looked like a farmer but he also had something of the aspect of a Yogi. He told Rinpoche and his father to go to the other side of the house to the cave of eight Mandalas of eight Anuyoga Tantras. When they entered the cave they began to recite the Heart Sutra of the Mahayana. They went all around looking at everything. Some parts of mandalas were visible but it wasn’t easy to distinguish which mandalas they were. When they arrived back at the door they had finished the recitation of the Sutra and then Rinpoche woke up.

Rinpoche told his father about the dream. One year later when he went back to his home he heard a visitor telling his father about a special Lama, and describing his house and the chörtens. Everything was precisely like in his dream. Immediately he persuaded his father to accompany him there. They arrived after a three day journey on horseback. The house and the appearance of the Lama were exactly as they were in his dream.

“The first time I met my Teacher Changchub Dorje I was a little surprised because his appearance and his way of living was just like an ordinary village farmer. He wore very thick sheepskin clothes and big, thick sheepskin trousers because it was cold in that country. Until then I had only met very elegantly dressed teachers; I had never seen or met Teachers who looked like that. The only difference in his appearance from a normal village man was that he had long hair tied up on top of his head and conch shell earrings and a conch shell necklace. I remember that when some important Lamas went to visit him they felt shy about paying respect to him. How can important teachers pay respect to a poor man? But Mahasiddhas are not always elegant or dressed like monks and nuns.

Although I was a little surprised, I had no doubt that he was my Teacher because of the dream I had had one year before. I thought this dream was very important. Then I followed him and I had no doubt.

“Until I received direct introduction from him I only had a kind of constructed faith, not really natural faith. I had spent many years in a college where I studied many Sutras, all the philosophies, and all the different Tantras. I thought I was a scholar and I knew everything. I was very proud. I went to see my teacher Changchub Dorje, not because I didn’t know the teaching and I wanted a teacher but because of the dream I had had.”

During the time Rinpoche spent at Khamdogar, Changchub Dorje asked him to assist in his medical activities and also to write down his termas. While attending to his patients Changchub Dorje was simultaneously receiving termas and dictating them at intervals. In the evenings Chögyal Namkhai Norbu would copy them in neat writing and was surprised at how they were perfectly coherent. At first he always thought, “This teacher is not giving any teachings. I’ve spent a long time here but he is always asking me to work. He never gives me teaching.” He was always treating people, giving information and advice to his students and chatting. None of this seemed like teaching in the way Rinpoche was accustomed to being taught.

Changchub Dorje’s damaru. Photo courtesy of Raimondo Bultrini.

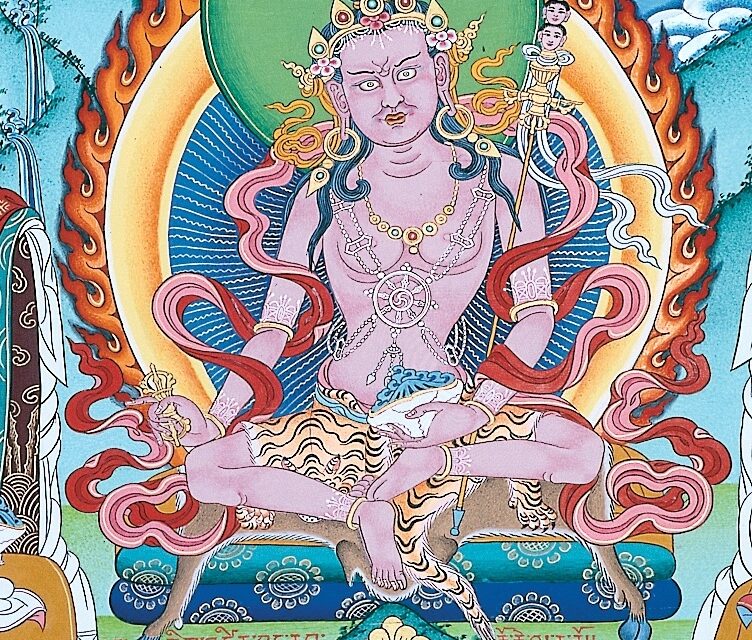

“I always received many teachings when I was around teachers. Also at Khamdogar I received transmissions, instructions and initiations from two very good disciples of Changchub Dorje: one called Aksoden and also his son, Gyurmed Gyaltsen, who was very learned. I was also accustomed to receiving Tantric style initiations. I always felt it was essential to receive initiations from important teachers. So I asked Changchub Dorje to give me an initiation on the special day of Guru Padmasambhava, on the 10th day of the 6th month. He said that I didn’t need it because he had already given me an initiation. The day I arrived he dreamt that he put a crystal rock on my three places and he had given me initiation in this way. I said, ‘That was your dream. I didn’t have the same dream. It doesn’t work for me’, and I insisted. So finally he agreed to give me his special terma (gter ma) teaching of the Xitro (zhi khro), the Peaceful and Wrathful Mandala. This is the only formal initiation I ever received from him. It is not a very complicated initiation, like the Kalachakra, but it took my teacher Changchub Dorje the whole day to give it. Sometimes he could not see well enough to read the words. Sometimes he was reading the notes that explained what to do and he was trying to do it. The initiation was a teaching from his own terma but he was going ahead like that with great difficulty. When the initiation was finished his students and I did a Ganapuja together quickly. My teacher was there but he didn’t take part. Then it was already late and dark, so I stood up and said, ‘Thank you very much.’ And I began to leave.

‘Why and where are you going?’

‘I’m going home to sleep now. I want to go back to my room and go to bed, because today I received an initiation and I am very satisfied.’

‘We didn’t do anything.’

I was very surprised. He had spent the whole day giving me an initiation.

‘Sit down!’ he said. I thought, ‘This master is really very strange’. I sat down at once because at times he was a bit fierce and if one didn’t behave well he was likely to get cross. My father also sat down. After a little while he started talking. At first he spoke in a very simple way to clarify what is meant by the necessity, the importance and the methods of direct introduction in the Dzogchen teaching. He said to me: ‘You studied for many years in college but your mouth is logic and your nose is Madyamikha’. You can’t understand, you can’t get in the knowledge in that way.’ Then he gave a direct introduction. He gave me the example of the difference between looking through eyeglasses and looking in a mirror. If you don’t know how to look inside yourself all the explanations of the Dzogchen teachings become other points of view. Before then I was convinced that I had really understood the tawa, the point of view, of the Dzogchen teachings. But then I realized that all my learning was external – just something to study, analyze, talk about and think about. Now I saw that what is called tawa is something alive, really related to our condition – something to work on in oneself.

He also taught me that the principle of Guruyoga isn’t the form and the system according to lineages; the real principle is the presence of the union of the state of all the Masters with our own state without any limitations. Without this principle, even if you do a very elaborate, formal Guruyoga there is no sense in it. We have to go beyond all the limitations of lineages, etc. So in a few words he taught me many things and how to find real presence.

After the direct introduction of course I really discovered what the Dzogchen teachings mean. Changchub Dorje went on talking for about three hours. He explained the base, the path and the fruit and all the essence of the Dzogchen Teaching. I understood everything very clearly. But after a while it seemed as if he was reading a Tantra from memory and the words of the explanation were becoming more and more difficult to understand. He was really a strange Teacher, a great Terton. He went ahead like that for another half hour. In the end he saw that I no longer understood. Then he stopped and said, ‘O.K. Now you can go.’

“My castle of concepts had crumbled and I had finally discovered what Dzogchen is and what the essence of all teachings is. This is what ‘Root Teacher’ means. Later, when I read again all the teachings I had received up until then, I discovered it was my fault that I had not understood before. It was not the fault of all these teachers. The real meaning of Root Teacher is the one who makes us discover our real nature and then we discover the value of all Teachings and Teachers.”

“After I had received the introduction and discovered what Dzogchen really is, what my real nature is, I saw in a completely different way. Before that I didn’t understand that everything my Teacher did was related to teaching. He was always asking me to do service and to work to prepare medicines etc. Sometimes he would say strange things. He was also breaking down my attitudes. Even though I was not a monk I had always been in college where everyone behaved just like monks, so I also dressed like a monk and had learned to have the same attitudes as a monk. But I had only received two vows: one was to wear clothes that showed one was a follower of Buddha and the other was a vow of Refuge. I did not have any other vows. But the rule of the college was that we should behave like monks. So I had that kind of attitude very strongly. For example, if I saw nice females I would feel afraid and I would escape. Before I received these teachings, if there were some very nice young nuns nearby my teacher Changchub Dorje would say to me, “Do you like these nuns? They’re nice looking, aren’t they?” I would blush. So as soon as I saw any nice looking nuns I would try to escape, otherwise my teacher would make these kinds of comments. That is an example of my attitude at that time. But, later after I had received direct introduction, even if my teacher said something as a joke I understood very well that everything he said was related to the teaching and instructions.

Compiled by Nina Robinson

This is the last short biography in our series Our Master’s Masters.

You can also read this article in:

Italian