Fabio Risolo

Born in Italy in 1958, Fabio Maria Risolo holds a degree in Philosophy from the University of Naples. He has taught at high school and university and is currently a Head Teacher. Fabio has been actively practicing and following the Dzogchen Teachings of Master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu and is a Santi Maha Sangha Base Level and First Level Instructor.

The word

In the following pages I will deepen the theme of the Master’s relationship with the disciple, and the value of his word, also through references to Western culture.

In Plato’s Phaedrus, when illustrating the myth of Theuth, the author brings attention to the written word, considering the oral one to be superior. The Athenian philosopher emphasizes that the written word is not alive because it is crystallized forever in writing and thus unfaithful to the unique event, which takes place when one person faces another.

The written word does not arise from the authentic and unrepeatable cognitive and communicative experience, which is established through listening and the maieutic dialogue [the Socratic method of eliciting knowledge by a series of questions and answers. Ed] between master and disciple. Only in this case does a direct transmission from body to body, from heart to heart, and from mind to mind take place. It is interesting to note in this regard that Socrates, like Jesus and the Buddha himself, wrote nothing.

Spiritual masters of all paths, and in particular of Dzogchen, highlight how the intellectual knowledge that comes from the study of books has nothing to do with live and direct transmission.

Once written, the word fatally detaches itself from its author and becomes the object of interpretations that very often do not correspond to the intentions of its author. It can also be misrepresented and used in an instrumental way. The written word becomes replicable and modifiable through quotations of parts of the text detached from the context in which they arose and can therefore be manipulated indefinitely, as is very often the case nowadays with social media.

But what is the specificity of the word of one who possesses knowledge?

In his dialogues, Plato explains that the word of the master, as well as authentic selfless love, derive from the daemon [something between mortal and immortal, since all that is daemonic is something between God and what is mortal. Ed], that is, from being inspired. The purpose of the “divine madnesses” (theia mania) is to connect the divine with the human, to act as a bridge between the higher truths and man, to put the invisible and visible dimensions in communication.

The word that comes from inspiration and is used by he who pronounces it, serves as a channel, a medium, or a “messenger”. Its author is ready to experience a clear and invisible force that expresses itself through him. However, he would be mistaken in believing that his own abilities, the same inspired voice that passes through him, is himself or something from himself. If he thought in this way he would confuse the current with the generator, the sunray for the sun, or the reflection for the mirror. It is not a question of being proud of one’s abilities or of one’s role as an intermediary for one must really beware of self-satisfaction.

Potentially we are all messengers, although few of us are able to be pure and transparent vehicles of the word as a manifestation of our being that possesses the clarity of vision. We must complete a preliminary path of presence and awareness. Through maieutic dialogue Buddha and Socrates tried first of all to lead their disciples to the understanding of the impermanence of everything (objects, things, people, emotions, thoughts). Only through authentic presence of our emptiness is it possible to recognize the voice of the daemon, which arises from that silent atopic space, and hence abide in our essential nature.

The authentic word as the ineffable voice of being is what Hölderlin called “the flower of the mouth”. And Heidegger recalled that, in Japanese, the character corresponding to “word” is pronounced KOTO BA. BA translates as “petals”, KOTO means “the breath of quiet”. So KOTO BA means petals that blossom from the breath of quiet, from silence. When silence is expressed in images it gives rise to petals (words). Rilke adds, “Oh spring-mouth, oh you giver, you mouth / Of the inexhaustible One, of the Pure, speak”.

He who possesses knowledge, a spiritual master, even more than a poet, is an inspired person, someone who is spoken to by the sibylline and prophetic daemon of which Plato spoke, and who manifests his self-originated potential without interruption, making it possible for his disciples to recognize their own essential nature. This is the meaning of the transmission.

But a master is not such because he knows or understands everything, but because he is always in contact with his own essential nature, he is one with it, and for this very reason he is able, through teaching, through transmission, through the word (but certainly also in silence), to arouse in the disciple the push towards the path and recognition. He does not tell the disciple what is right or not right to do, but teaches him or her how to bring out the essential part of himself, (first of all by unmasking his ego and his judging rational mind) and then showing him how to “give birth to it”.

The master is not a God; the daemon speaks to him and through him in every moment and in particular in the moment of the transmission, when he speaks to the disciple, and simultaneously loves and lives in the dimension of eros.

He loves his disciples as he arouses in them the desire to know their essential nature so that they finally find themselves within themselves and in turn recognize their own demons and follow a path. Because the highest form of love, explains Diotima to Socrates in the Symposium, is love of knowledge.

But, for himself and in himself, the master maintains the simplicity of humility in his life. However, in addition to being present in every moment of life, he has an extraordinary quality: he is a conscious channel of being. This is the reason why, when questioned, the oracle of Delphi could say that Socrates was the wisest in Athens, certainly not because he had accumulated facts, knowledge, power, prestige or fame, but because he knew at least one thing: one who knew nothing, and was himself nothing, lived, to put it in Buddhist terminology, in the state of prajnaparamita, was atopic, did not dwell in any place or concept, and was eternally open. Not dwelling in any place means dwelling in all places, being invisible energy beyond time and space. And above all he was the only one in Athens who was aware of his “being nothing”.

For this reason he explained to his disciples who asked him to flee so as not to be killed by the Athenian politicians (paradoxically he was accused of misleading young people from the truth) that he wanted to remain true to his own teaching, even at the risk of death. Socrates lived with his disciples and shared every moment of his daily life with them. They were his family and he was with them all the time because teaching also meant showing them how to live. Letting them see him die would give his disciples the last decisive teaching, that of complete integration of awareness in behavior.

In Socrates, like all teachers, history repeats itself. He had never judged his disciples, not even when they had tried to get him drunk in the Symposium, tired of having a perfect man before them. But with his silence he taught that he could drink with awareness, while they, who challenged him to the sound of Greek red wineskins, fell asleep in total absence of presence. In the Dzogchen teaching awareness of our behavior means knowing what we can and cannot do, working with our capacities and circumstances.

Building a conscious relationship with the master

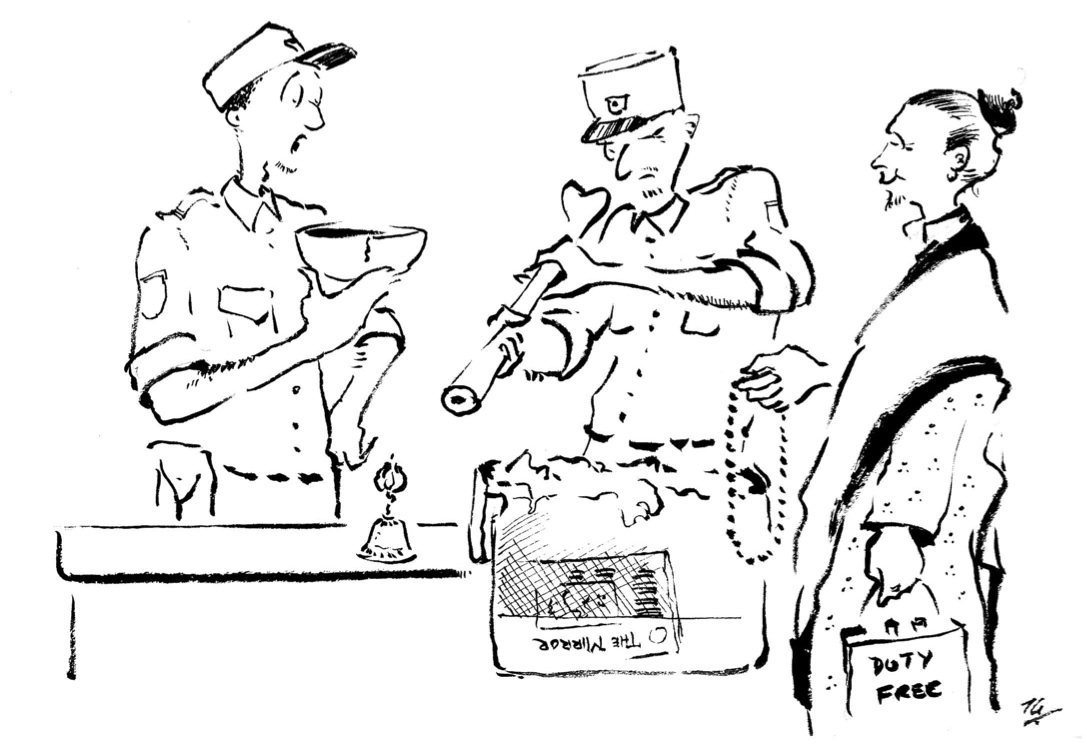

The gift of the transmission of knowledge comes about through the word. After that the disciple, even if he has recognized the master as the source of all good, generally finds himself having to face his own ego, the desire to be recognized as the best, and to want everything for himself. This confrontation is inevitable and unavoidable. It is from overcoming it that the possibility of integrating within oneself, in an effective and concrete way, the empowerment of the teacher and of realizing oneself derives. To do this, we must firstly recognize how we project onto him our entire psychic world – our desires, emotions, fears, and aspirations – as in a mirror.

Socrates liked to point his disciples towards love for self-knowledge. To do this he set the disciple in motion and urged him to look into himself. But Agathon, Plato tells us in the Symposium, wanted to achieve maximum proximity to the master’s body in order to absorb all his knowledge and deluded himself into thinking that he could possess his beloved master. But knowledge cannot be possessed, only transmitted, as suggested, through references, allusions, symbols, conveyed by the word of the transmission.

In reality, Socrates himself is empty of knowledge, since he is simply a pure lover of knowledge, who inspires in his disciples the same thirst for knowledge, thanks to his love and his maieutics. In fact, knowledge is possible only when we are empty, when “we know that we do not know”. The master first of all teaches how to preserve this emptiness as a primary condition in order to make the transmission of knowledge possible.

The disciple therefore initially projects his own solar part onto the master, attributing every quality to him and seeing him as a divine being. The gift of existence and the recognition of one’s value are expected from him. Once the transference has taken place, the disciple imitates the model and tries to perfect himself to please the master (as the lover does with his beloved …), to have proof of being. Up to a certain point this process is very useful since it allows for purification. But the disciple must become aware, so that it is possible to withdraw the projection of his own solar and divine part on the master and recognize his own potential in himself. This is done through the practice of Guruyoga.

In Tibetan the Sanskrit word Guruyoga (union with the master) translates as lamai naljor, and indicates the recognition that one’s own deep nature is the same as the master’s and therefore one is non-dual with him. The disciple awakens his own daemon through this recognition, thanks to the reflective function of the master. The practice of Guruyoga is infinitely more important than the transference in psychotherapy, because what the teacher allows the disciple is not just to free himself from neuroses, but spiritual realization. More precisely through the word of the master the disciple receives the empowering flow that comes from the lineage and this allows him to work with it, absorbing its potential, until realization. This is a unique and extraordinary opportunity.

This is the inner process, which does not happen without falls, disillusions, and suffering, which the disciple can go through if he meets an authentic teacher who knows how to direct the disciple’s transference towards awareness and freedom and not egotistically increase his own personal power. Finding such a master is by no means easy.

Certainly the crucial moment takes place when the master shows the disciple, as in a mirror, his darker aspects and projections that are most difficult to accept, causing him a real shock. The master can do this right from the start by cutting through the disciple’s ego (the classic example of Gampopa with Milarepa) or only in a more advanced stage. In each case the disciple must come face to face with the vision of his own condition of emptiness. At this point he may feel nothing in front of the master with the risk of becoming depressed or, conversely, have a proud reaction by detaching himself prematurely from him, believing that he himself is the Guru.

The teacher guides this process, remaining present and aware, without being captured by the projections. In this way the disciple can transfer the archetypal image of the master and his empowerment within himself.

By loving the disciple the master teaches him to love, making him progressively free, that is, allowing him (and this is the decisive point) to recognize his own solar part, the nature of the mind. It is about discovering that we ourselves are the master, the king who creates everything, the Kunjed Gyalpo.

Thus a conscious and unshakable devotion to the master can arise in the disciple, which manifests itself in daily life and especially in the commitment to the sangha, in which he now recognizes the living body of the master.

The relationship with the master and his empowerment remains present regardless of whether he is still alive in the physical dimension; this relationship and its potential for realization is beyond time and space.