Raimondo Bultrini continues his account, based on his diary and his impressions, of his travels with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu through China and Tibet in the early months of 1988

Honor to the masters of the past

To my father and mentor

To the sisters and brothers of the Vajra

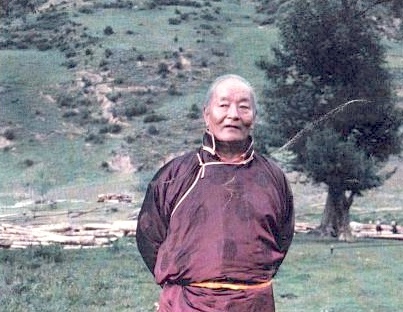

Raimondo in 1988 in front of Changchub Dorje’s house in Khamdogar, where the master’s body was still preserved in salt.

As the only Western witness of all the eight months of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s journey between China and Tibet in 1988, I have always felt the duty to recount at least the passages that I believe to be more significant of that unique and unrepeatable experience. A duty to all of Rinpoche’s students, not only the youngest, who have little knowledge of this important period in the life of the Master. I could write a long article about each day on its own and you will forgive me if accumulated personal causes have prevented me from dedicating myself completely to a more detailed summary. But here I would like to condense as much as possible the meaning of that journey that had been prepared in detail months earlier.

Rinpoche had just completed a tour of seminars and retreats in various parts of the eastern hemisphere and had interrupted the rhythms imposed by the constant requests from practitioners from all over the world inviting him to teach Dzogchen in order to spend that period between China and Tibet. In China, where there was still no gakyil for the Community, his books on Bon and ancient Tibet were already milestones of Tibetan historiography. In the months that I had the good fortune to share in close contact with him, I was able to observe the transition of the Master from the dimension of the Western culture of Italy in those years – with an almost equal population of conservative Catholics and Communists – to a world of traditions in which everyone follows Vajrayana Buddhism and largely saw Rinpoche as a source of blessing rather than wisdom. Rinpoche will overturn that point of view on several occasions by speaking to nomads, shepherds and farmers, but also to professionals and politicians, about the methods of self-liberation that through the Guruyoga of union with one’s masters makes the practitioner indivisible from the source of the greatest possible blessing, the state of contemplation.

In any case, Rinpoche was aware that he could not disappoint those who approached with their heads bowed to receive the hands of the guru who was identified as the intermediary of the divinity itself. “It’s different here. What else can I do if someone goes after the forms? At least I can recite a mantra for them,” he said one day smiling when I asked him why he had never adopted that gesture in the West. He had just finished touching hundreds of heads, reciting as many mantras and was donating countless objects of protection to those who had requested them by blowing sacred syllables on them. The master noticed my curious attention and could read my thoughts like an open book. Then he talked about when he was in Turin many years earlier, during a retreat he had met a Westerner who wanted to be a Tibetan in all respects. “I had just finished talking about guruyoga” – he says – “and we sounded an A before dedicating the merits. Eventually a man approached my seat and respectfully asked me if he could have a blessing. I told him that he had already received it with the practice of union, but he insisted and then I asked what kind of blessing he wanted. ‘I don’t know, do something, touch me’ …” We laughed for a long time and the scene often comes to mind given the ancient intensity of the master/disciple relationship far beyond physical and mystical contact.

Most of the time Rinpoche wore the same red windbreaker and only dressed in elegant religious garments when asked to lead ceremonies and ritual initiations. There is also a photo with an elegant heavy velvet dress that came down to his feet subtly embroidered with Tibetan motifs. Rinpoche said it was the robe of some aristocratic ancestors who were advisers to the king.

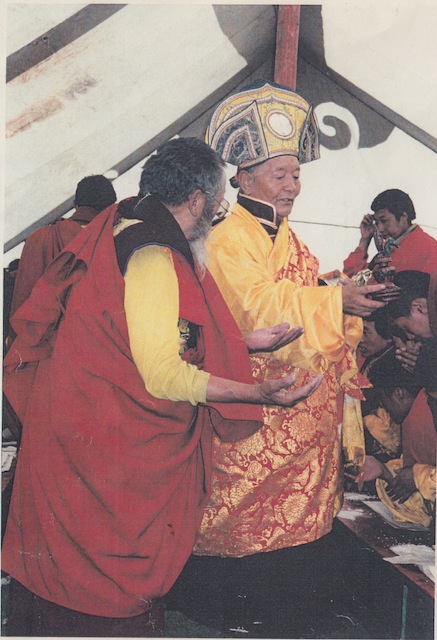

Rinpoche at Galenteng giving an initiation.

Personally I had never seen the master wear religious robes in the West, and I don’t think he ever did, but in those months – in addition to the photo with the reddish purple chuba – I took pictures of him in ritual clothes on at least two special occasions. The first time he gave an initiation to more than a thousand nomads from the area around the monastery of Galenteng wearing a red embroidered cloak with gold patterns and a yellow shirt that belonged to his uncle Khyentse Wanchug. We were under a huge white awning open at the sides and used as a gönpa with hundreds of men, women with turquoise in their hair and children on the lawn that was also crowded with horses and riders and monks in charge of the sang incense whose cypress-smelling smoke enveloped everything.

The monks at Galenteng and the Sang ritual

The second occasion was the ritual to consecrate the stupas in the village of his master, Changchub Dorje, during which he wore a red-colored cloak with blue bands on which the wise men of the lineage were printed. On all these occasions the ceremony took very different forms outwardly from those that I had practiced at Merigar and the Western gars. It is difficult to describe the intensity of the emotions that were released, even it seemed in the Master, by the magic of those moments, between the attentive gazes of faces with ethnic features unchanged since time immemorial, the music of the long horns and the dark rumble of the great drums, the odorous cloud with its pleasant smell used for purification even among American Indians. As Rinpoche, who had witnessed rituals among the Navaho similar to the Tibetan sang, told me, “Many of them mistook me for one of them and asked which tribe I came from”.

His expedition, which he began in China as an academic, switched between three levels when he arrived in the eastern and western highlands: that already mentioned of being venerated, that of the yogi-pilgrim in the places of his mentors and masters (including the sacred Mount Kailash in the company of a seventy students like me who came from all over the world) and finally, on a more political level, that of negotiating delicate relations with the Chinese authorities. It was in the first and second part of the trip (described briefly in a small book by Shang Shung published shortly after our return to Italy) that the core of ASIA’s projects was born and entrusted to Andrea Dell’Angelo, who returned with the Master and Giovanni Boni to the same places to start work on them.

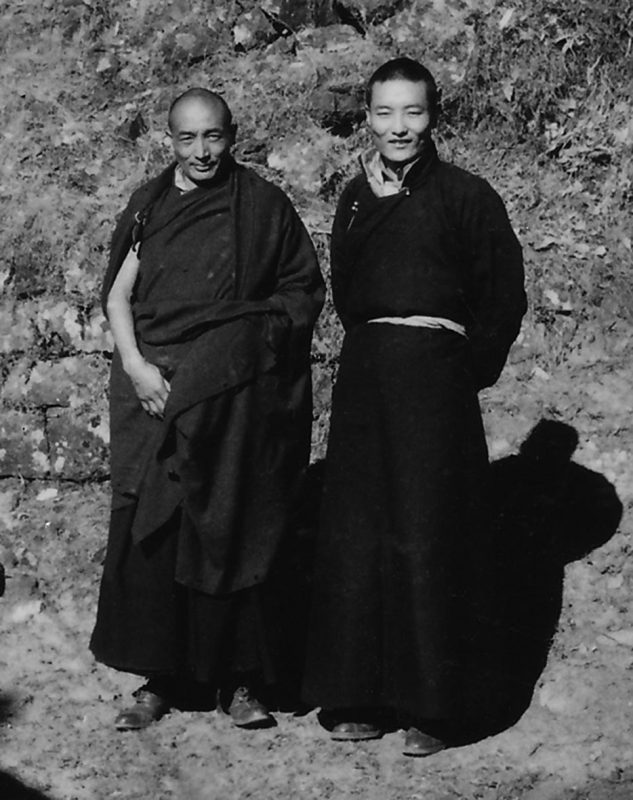

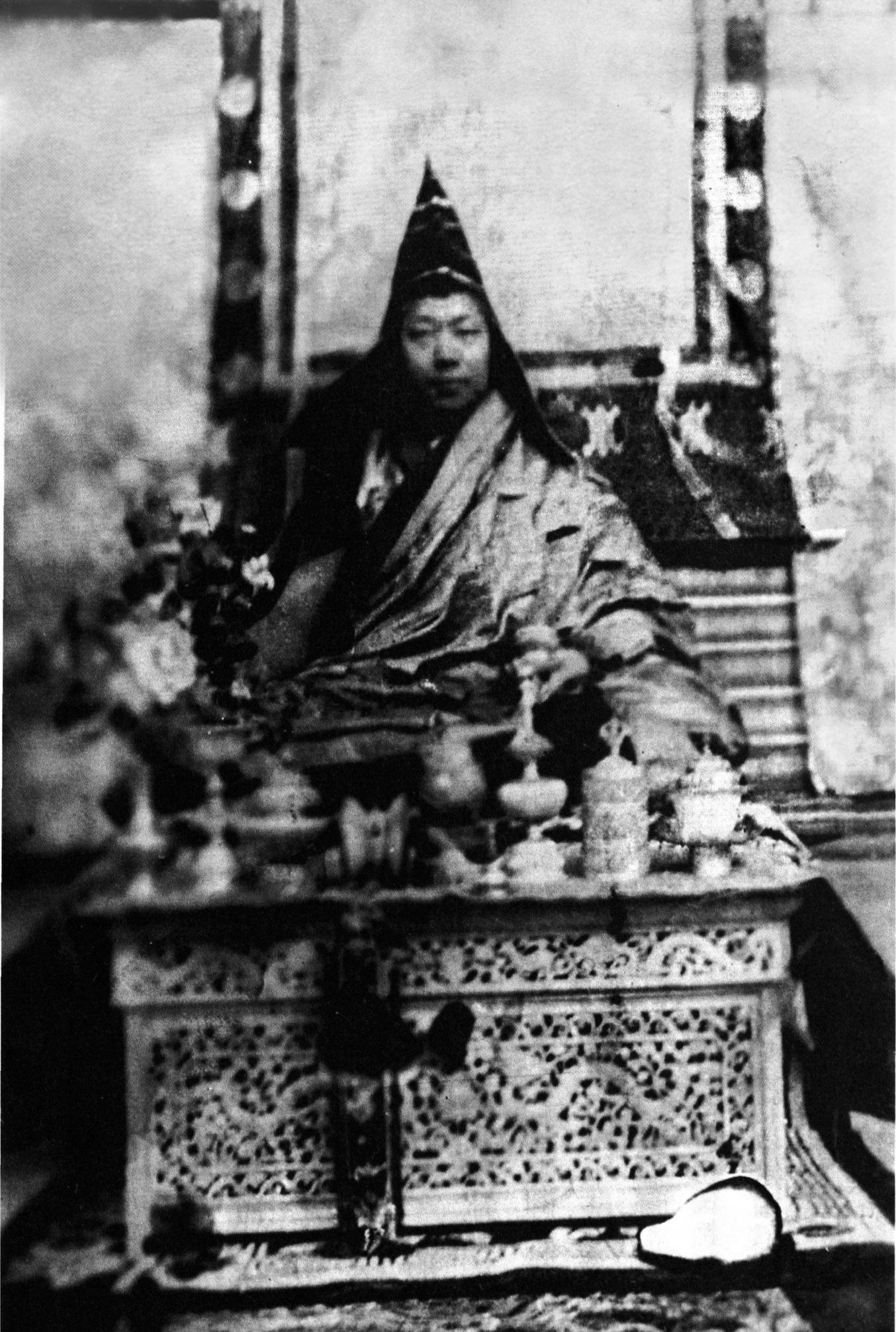

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu and Gangkar Chökyi Senge, 1953.

In his approach to the officials who would support future projects, Rinpoche was facilitated by the causes he had already sown in his youth. In fact, scholars and professors from the main universities of Tibetological studies who had been his students or had known him in the 1950s as a representative of the Tibetan monasteries introduced him to local governors and Tibetan and Chinese party leaders. In 1953 he had been invited by the Chinese Communist Youth to visit Chengdu – which will be one of our stops – and Chongqin. Then they had asked him to teach the Tibetan language in Menyag and for three years, until 1957, he was a teacher at the South-Western University for Minorities in Chengdu where he in turn studied classical Chinese and Mongolian. It was in this period that Rinpoche met Gangkar Rinpoche, a very important figure for his growth both intellectual and human, so much so that passing near his monastery Rinpoche made us all buy blankets manufactured there in order to finance the yogis who continue his lineage.

The meeting that marked the turning point for Chögyal Namkhai Norbu took place in 1955 when he was still 17 and living in Chengdu. A dream took him to his master Rigdzin Changchub Dorje in Khamdogar or Nyaglagar beyond the borders of central Tibet, where we will go in early summer.

The Chinese openings

One of those regular students who had attended his lessons in Chengdu and other centers in the province and who became an important official of the Tibetan Autonomous Region in Beijing, took care of the issuing of all authorizations and visas for us, including mine as Rinpoche’s assistant. We will meet many of the ex-alumni in Chengdu and in Kangding, an important city with a Tibetan majority and a famous technologically advanced university center. Here the welcome in the most technologically advanced university in Sichuan was such that our group had to pass between two lines of students with traditional white khatags and the red bow of the Communist “pioneers” as well as teachers and locals waving Buddhist flags (the traditional snow lion is forbidden) and the red ones of China.

Political leaders and administrators, in line with the Party’s new, more open and tolerant approach, no longer saw the idea of preserving – as Rinpoche proposed – the ancient culture of the Tibetans as a danger. Even the tulku, the so-called “living buddhas” according to the Chinese definition, had been in a certain way “rehabilitated” after the excesses of the army and the persecutions of the Cultural Revolution (in the 90s a law would entrust their selection to the Party that had a claim on the very choice of the main reincarnations such as the Dalai and the Panchen Lama).

Rinpoche often spoke of this ancient institution, started by a Kagyupa master in the 13th century (and “copied by all other schools”, he said), of which he was rather critical for the overly distorted use of the title and the excessive material power of institutions that count on the fame of the tulku. He anticipated what the Dalai Lama himself would say many years later, “As the degenerate age progresses, and as more and more reincarnations of high lamas are recognized, some for political reasons, an increasing number of people have been recognized in inappropriate and questionable ways, as a result of which enormous harm has been done to the Dharma”. The proof – he writes – is that China has created a special political commission for religious affairs with the power to “certify living Buddhas”, as the Party calls the alleged “reincarnations”. In 2017 in the New York Times His Holiness used even clearer and unequivocal words about how to prevent the Chinese from any possible stratagem to replace him, “All religious institutions, including the Dalai Lama, developed under feudal circumstances” – he said – “corrupted by hierarchical systems, and have begun to discriminate between men and women; they have (even) reached cultural compromises with laws similar to Sharia law and the caste system”. “Therefore (with me), the institution of the Dalai Lama, with pride, voluntarily, has ended”.

Rinpoche had repeatedly explained to me and to other traveling companions that the fame and prestige of the title among the Tibetan populations did not always correspond to the qualities of lamas and abbots in pompous clothes, title-holders of labrang – the estates of monasteries – whose administrators or Gekos were often at war with others for influence over villages and a source of wider revenue. His uncle Khyentse himself and his predecessor had to endure campaigns of discredit by the great monasteries and their own Gekos for their opposition to the circuit of dharma business and for their long periods spent in hermitages to practice.

Rinpoche returned to his country 34 years ago with the intention, achieved, of laying the foundations for ASIA’s activities in that year, but he understood that the conditions existed for the birth of the Chinese Dzogchen Community, today an integral part of the international one. At different levels of public administration from Beijing to Chengdu, from Qamdo to Derghe, many wanted to support his ideas for an integration between two apparently so separate worlds as Tibet and China. Rinpoche made it clear to everyone that the two neighbors, albeit divided by politics, had long had intense cultural and religious exchanges, ever since Buddhism spread from India to China through the first pilgrims. He recalled that many emperors had converted to the Vajrayana and – as the powerful Mongol khans had done – received numerous spiritual teachings from different Dalai Lamas.

Since his arrival in Beijing the Master said that he intended to open schools and create community services especially for nomads, but also to start seminars for monks of traditionally neglected traditions. He knew it would not be easy but that historical period was perhaps the only open window within the great wall of Chinese ideology. In fact, after Tien an Mien, China closed again and radically transformed the landscape and lifestyle of a large part of the population. It was thanks to ASIA that he was able to conclude his projects avoiding the fate of other independent international non-profit organizations forced to leave the country. He did this without ever abandoning the original idea of supporting communities that are “collateral” victims of a progress that was drastically changing not only the environment on the roof of the world but also the ancient and efficient systems of the livelihood of the tribes, especially the nomads.

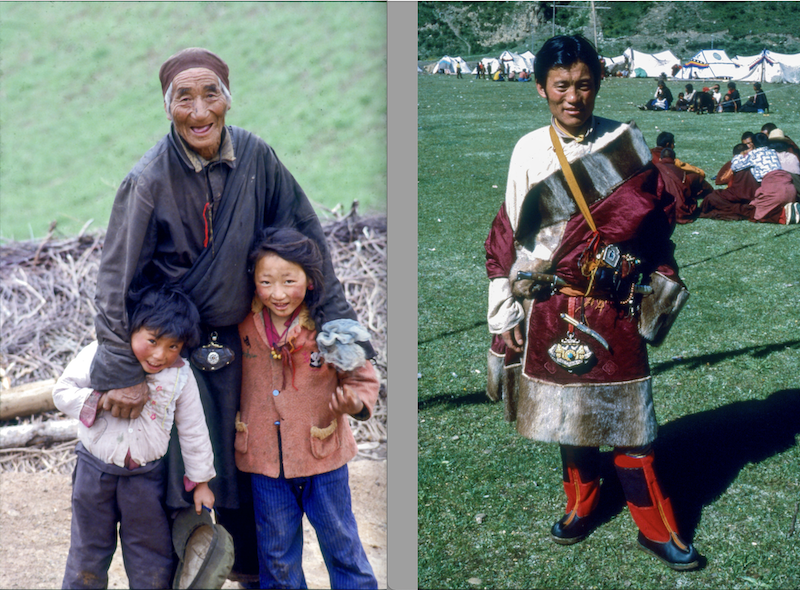

During the journey Rinpoche often spoke of the importance of these wandering shepherds in Tibetan culture (he wrote a book entirely dedicated to them) and of their relationship with the primordial nature. We will meet hundreds of nomads under their fabric tents used during short trips, or made of yak wool for winter residences. The Master would entertain them for hours by telling them stories of the exotic West, enchanting adults and children around the fire of the stoves, and listen to their stories asking them to explain what had happened to their lives after the arrival of the Chinese. He knew that the experiments of the nomadic cooperatives had failed but that everyone feared some other initiative to limit the freedom that families had always enjoyed to choose pasture for animals. (Today, unfortunately, the nomads mostly live in Chinese-style compounds and have been forced to lead a more sedentary and controlled life).

During the journey Rinpoche often spoke of the importance of these wandering shepherds in Tibetan culture (he wrote a book entirely dedicated to them) and of their relationship with the primordial nature. We will meet hundreds of nomads under their fabric tents used during short trips, or made of yak wool for winter residences. The Master would entertain them for hours by telling them stories of the exotic West, enchanting adults and children around the fire of the stoves, and listen to their stories asking them to explain what had happened to their lives after the arrival of the Chinese. He knew that the experiments of the nomadic cooperatives had failed but that everyone feared some other initiative to limit the freedom that families had always enjoyed to choose pasture for animals. (Today, unfortunately, the nomads mostly live in Chinese-style compounds and have been forced to lead a more sedentary and controlled life).

The Nature of Tibet

It was on two occasions, which remained etched in my memory, that Rinpoche explained the relationship between Tibetan mystics and nature, in the years when environmental concerns were not yet the topic of the day. One morning as we were walking through a forest in eastern Tibet, much greener than a western one, he said that every tree was an object of contemplation for him. In my notes I saw that I had had a flash: I imagined a world where everyone lived in symbiosis with their own tree as could happen in one of the many dimensions that the Master told me about. I also thought of the fact that it was under a banyan tree that the Buddha would be enlightened, and under the same branches he emerged from the womb of his mother.

In mid-May the snow still had not melted on the high altitude meadows that were filled with yellow and red flowers under skies of a blue that I had never seen before. We stopped a few kilometers before the monastery of Rinpoche’s uncle, Abbot Khyentse Wanchug, and got out of the car to follow a dirt side road on foot and here an enchanting lake surrounded by fir and juniper trees appeared. Rinpoche gazed intensely at the colors and magical appearance of that stretch of water that seemed like a transparent turquoise set between the snow and the intense green of the trees. He said he had come here with his abbot uncle when he was 11 and he was so enchanted that he wanted to build a monastery here. “Since then” – he told me – “every time my mind is disturbed by external elements and apparently unsolvable problems, I always come back here, to this lake”.

He explained that when he was little he had a very different idea of priorities having been educated to become a teacher and potential head of some monastery. But the importance of religious institutions became relatively secondary for Rinpoche when at Khamdogar he met his master of Dzogchen, Changchub Dorje, whom I hope to be able to talk about in another part of this story.

That morning on the shores of the lake of his childhood, the Master explained his new idea about how to make use of that enchanting place. “If possible I would like to build a place of practice here that can also be used by our people in the international Community,” he said. I don’t know if that idea was put into practice later on, but I fear that the political tightening and politicization of the religious authorities may have made this part of Rinpoche’s program difficult.

To give an idea of the changes that had taken place at the time of his arrival, the Master arrived in Beijing from Hong Kong at the time when there were still 9 years until the island returned to China, an event that according to him could change the power structures in Beijing as well. There had been perestroika with the first Russian liberal reforms and Deng Xiao Ping in Beijing had opened China to the world, even hosting the first envoys of the “enemy” Dalai Lama in Lhasa. A year after the Master’s journey, the Tien an Mien revolt was, in fact, an attempt to reduce the power of the northern Mandarin-speaking ruling class. From the world of traditionally more open southern businessmen and politicians came a powerful sympathizer with the rioting students, the Party general secretary Zhao Zhiyang himself, who was later dismissed.

It was easy to understand how by applying the basis of Dzogchen the Master acted according to the circumstances that required respect for the laws but also for the customs of the countries we encountered. Outwardly it was easy for him, even if on an emotional level he was accompanied by a feeling of enormous sadness ever since he had to obtain permission from foreign people to see his Tibet again. Over time the Master self-liberated the obstacles of deep and painful passions, even the sense of guilt that he told me he felt for having endangered his family as a “living buddha” and therefore an enemy of the people.

Here I would like to anticipate another important aspect – it certainly was for me – of that journey in 1988. As we rode up the plateaus beyond Ya’an to Tibet, Rinpoche asked me what I thought of His Holiness. I realized I did not have a precise answer, knowing little of the methods of his Gelugpa school. I replied that I knew him more as a political leader than a religious one. Then the Master told me a story that would become an obsession for me in the years to come, even if at that moment I did not realize its importance for the very future of Tibetan culture and its most famous representative, the current XIV holder of the title of Ocean of Wisdom. He explained that the anti-sectarian movement Rimed with which he identified himself had had a strong reserve until the 1970s towards a form of “Guardian” or protector cult with which the Tibetan leader was associated. In fact, the cult called for “taking refuge” in a being considered the defender of the pure Gelugpa doctrine against any other type of “contamination”. When the yellow hats were in power and “they also minted coins”, Rinpoche explained to me one day in front of a large monastery in Derghe, “and they did not intend to hand over the power of their clergy to other schools”.

Only later did I learn that at the time of his “initiation” into the controversial “spirit” the Dalai Lama was surrounded by tutors and advisers who practiced the worship of a gyalpo being called Shugden, even though the official protector of all Dalai Lamas was Palden Lhamo. Consequently, “No religious person from the other three schools” – the Master told me -“ or other Dzogchen practitioners like me would have ever taken initiations from the Dalai Lama”. The cause was precisely that link between him and a “harmful spirit”, as the Dalai Lama himself will define it years later. “But now” – added the Master – “everything has been solved. His Holiness understood the divisive spirit of that practice and invited all Tibetans to stop it. Now I am ready to receive an initiation from him” (which will happen in Gratz, Austria years later, ed).

The reason for that old conflict became increasingly clear to me when, with the support of the Master and the exiled Tibetan leader himself, I worked on a book about the consequences of that affair for historical events that are still taking place. In the lamas of the cult China will find loyal allies for their strategy of replacing the Dalai Lama with a “tulku” educated by his internal enemies and Party advisers when he dies. They also went on to finance the noisy international anti-Dalai Lama campaign on the part of a pro-Shugden “coalition” accusing him of “religious persecution”, with public actions that had wide international repercussions but little practical effect.

But now I would like to come back to the stages of the journey since we left the Chinese capital Beijing, where the Master was staying at Donatella Rossi’s house in a compound for Westerners and I in the rented rooms for students at the University of Beidà, from where, shortly after, the first outbreak of the Tien An Mien riots that will end Deng’s more liberal era will ignite.

The evening of May 2 we landed in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan and still today the tourist gateway to Tibet, welcomed by a small crowd of relatives and Tibetans who had been informed of Rinpoche’s arrival. Among them was the sister of the Master, Sonam Palmo, slightly older and extraordinarily similar to him except for the long braids with turquoises and colored ribbons like an American Indian. She had come from Lhasa with her adopted daughter Phuntsok, now a doctor known to many people in the Community, wearing a brown wool cap, an abundant chuba that was out of proportion with the heat of the Chinese plain and from whose sleeves emerged a pair of gloves open on fingers that slowly and continuously rotated a mala. Rinpoche and his colorful procession – which did not fail to impress a group of Japanese tourists – also intrigued the young Chinese at the reception of the Minshan hotel who was accustomed to the presence of all the Tibetan ethnic groups in the city.

Part of the procession relocated – joking on the still unusual elevators in Tibet – to the room made available to the Master and his assistant by the Institute of Minorities. The director had sent a car to the airport and had come to personally make sure that the wise man from the West was comfortable. He also wanted us to try the super spicy Sichuan specialties right away even though it was already late in the evening. At dinner Rinpoche recalled his trip in the 1950s through this province and the state, when the Chinese had not yet reached the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and the Master had agreed to travel to various Chinese cities as a representative of the Communist Youth of Tibet. With those years in mind, he explained to the director of the Institute that it had always been important for him to know how a country’s society is formed in order to know the best way to behave in all circumstances and with respect. “When I arrived in Italy in the 1960s” – he told him – “after learning the basics of the language, I attended both the meetings of the Communist Party and Catholic parish circles in order to understand how people thought”.

The next morning, after a sudden unsolicited wake-up call on the national radio news at 6 o’clock, Rinpoche explained to me that very few of the Chinese interlocutors we had met knew how to distinguish between the priesthood and masters without a “church” who are considered to be practitioners of Dzogchen. I asked him in what spirit he could travel through a country like his, where – despite the recent opening – party politics seemed to play an increasingly important role over religion in every aspect of society. He replied that in all circumstances it is always better to reflect on the reasons that divide society and never take sides completely with one of the parties because you can lose the opportunity to act for the benefit of both. He explained that he had learned this teaching that was more practical than spiritual not from one of his dharma teachers or from his yogi abbot uncles, but from a brother of his father who was a prominent politician and vice president of a province. “This uncle” – said Rinpoche – “explained to me that authority and power came to him from his ability to expose criticism of the system but to always know how to find mediation. When I was 15 or 16 he told me, ‘You are young now but when you grow up never stay completely on one side or the other’.”

Jamyang Chökyi Wangchug. Photo courtesy of Master Bi Song.

The Master traveled to his Tibet filled with memories of the dramatic fate of friends from his youth, teachers, loved ones, a father and brother killed in Chinese labor camps, and the mysterious death of his uncle Khyentse Wangchuk, abbot of the monastery and spiritual leader of the village of Galenteng where we will spend many weeks. Khyentse was to be lynched and publicly shot along with three other masters, who were his friends and great practitioners, in the capital Derghe as “false living Buddhas, enemies of the people” and to demonstrate their human vulnerability. But three days before the execution, the abbot was found lifeless in the meditative position by the Red Guards of the prison where they were all locked up. Not only that, the other lamas died in different cells and at the same time.

In the same prison, Rinpoche’s older sister Jamyang Chodron, a disciple of all three, Khyentse, Shechen Rabjam and Drugpa Kuchen, was doing forced labor. She was the only one able to meet them, isolated as they were, and it was she who brought to the others the only message from Khyentse, a phrase about the Great Symbol that had been agreed perhaps in anticipation of what would happen to them, the same humiliating treatment suffered by other masters, forced to beatings, cruel trials and even to be ridden by fanatics with reins around their necks and summary executions. There are many details of the cruelties committed by the so-called burtsonpa (activists) as we will see again, and the Master describes them in the biography of The Lamp That Enlightens Narrow Minds translated by Enrico Dell’Angelo to which I refer for those who want to know more.

Hundreds of masters and disciples were fiercely tortured in front of crowds excited by blood and violence as “counter-revolutionaries”, “an obvious manifestation of the gyalpo” – the Master told me – “that feeds on man’s anger and provocations towards the order of primordial nature”. The world only later learned of the climate of terror that had been created in every family, often dividing children with opposing positions on independence from China and fidelity to the religion of their ancestors.

Rinpoche himself, in Indian Sikkim since ’56 without any connections with occupied Tibet, told me that until ’79 he was generally unable to learn anything about the fate of his relatives. But at the beginning of the 1970s, “the news of Khyentse Wangchuk’s death” – he explained – “reached me in a completely unexpected way. A teacher at the head of the Sakyapa school wrote to tell me that he had had a vision of my uncle reincarnated in my son Yeshe and so I learned that he was dead”. During his stay at Galenteng he will recount other details, including the unnatural death of two of his uncle’s accusers in front of the “people’s court”. But I refer again to The Lamp and later on I will recount an interesting personal anecdote concerning two other figures of former “revolutionary” torturers who are still alive.

To be continued in the next issue of The Mirror

You can also read this article in:

Italian