In this final episode of Raimondo Bultrini’s account of his visit to Changchub Dorje’s village in Tibet with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in 1988, at long last they meet the Master.

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu films one of the stupas containing relics of Changchub Dorje. Courtesy of the Merigar Archive.

The Elderly Disciples

In the morning we wake up early, as usual. Sonam Palmo and Phuntsog get up from their sleeping bags while I emerge from a pile of blankets that don’t always manage to protect me from the cold. Instead of one of Changchub Dorje’s elderly disciples, this morning it is a nun in her 40s who brings us tsampa with tea. By now I am used to it and without hesitation I swallow the mixture which I still do not know how to prepare by myself. Soon after, the same nun arrives with a bowl of water heated at a nearby house. In the bitter cold, washing with warm water is a real pleasure.

In the evening, walking with Rinpoche before bedtime, the sky is almost always free of clouds and a unique harmony reigns in the air. The usual star formation shows up punctually in the same spot, visible beyond the triangle of mountains that encloses the village. The diffuse light of a moon still low on the horizon outlines the contours of the bizarrely shaped rocks.

With the flashlight off, my senses alert, I breathe in at the top of my lungs a light, heady air, like a sparkling wine that makes me light-headed and gives me pleasant chills. Would I stay here forever, I wonder? Would I give up the chaos of my world for the long days of meditation and this nocturnal peace? Perhaps, but I can’t right now. I am too excited by the idea of a changing city, of the hustle and bustle of frantic lives, of running after dreams of wealth, power or just tranquility, of loving a thousand women, of a thousand men in search of ideals that are always impossible and ready to vanish, of the creation of millions of objects as fascinating as they are useless.

Here there is no visible goal and dreams do not immediately materialize by simply wishing them to. In my world, if I want to run, I have a fast car, if I wish, I can fly a plane. Here I only have my legs and arms to work with.

Tonight before I go back up to my room a star falls while I am walking and I find myself longing for a deep inner peace, communicable to all. A few years earlier I would have asked for something different, something much more practical. As of today I observe and reflect on the effects of a life devoted exclusively to the spirit. I carefully observe the lamas and hermit yogis, many of whom were direct disciples of Changchub Dorje. I do not know their thoughts; I cannot speak with them without the translation of Master Namkhai Norbu. However, I can reflect on their personalities from the way they behave, and from many other signs.

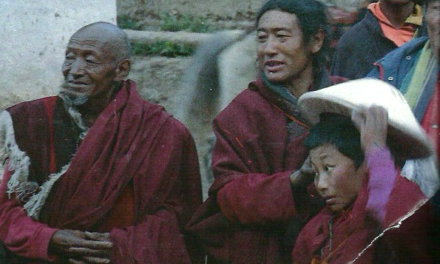

The Marlon Brando look alike monk.

One is tall and sturdy, with a Marlon Brando-like face. He gives an impression of inner strength and solidity. His imposing appearance and magnetic gaze make him a charismatic figure. I get the feeling that he has mixed opinions about me and some resentfulness due to my initial refusal of food. Indeed, he is one of our most diligent servants, and it is strange to see this imposing man, who was one of Changchub Dorje’s leading disciples, bow his head whenever he hands out food. My impression is that he has educated himself in humility, following the example of Karwang, who, however, seems to manifest it more spontaneously.

Small and agile is the elderly cleric with whom I attempted to sound the drum in the temple of the wrathful deities. He has a white beard gathered at the chin, a sign that commands respect among Tibetans. He must possess some musical talent, because in addition to teaching me the drum he plays the trumpet during all ritual ceremonies.

His eyes also possess something special, as if lit by a fire that seems to extend all over his dark red face. Perhaps he is a practitioner of “tummo,” the energy of the inner heat that develops through years of training one’s prana. But it is more likely that he spends most of his time sounding the drum where I met him, in the small temple at the end of the village.

He is the one who fills the air of the valley with sounds, and his association with the wrathful deities must have made him at once strong and intuitive. Indeed, he manifests a certain apparent detachment, while his eyes shine with unquenched passions inwardly transformed into mystical faith.

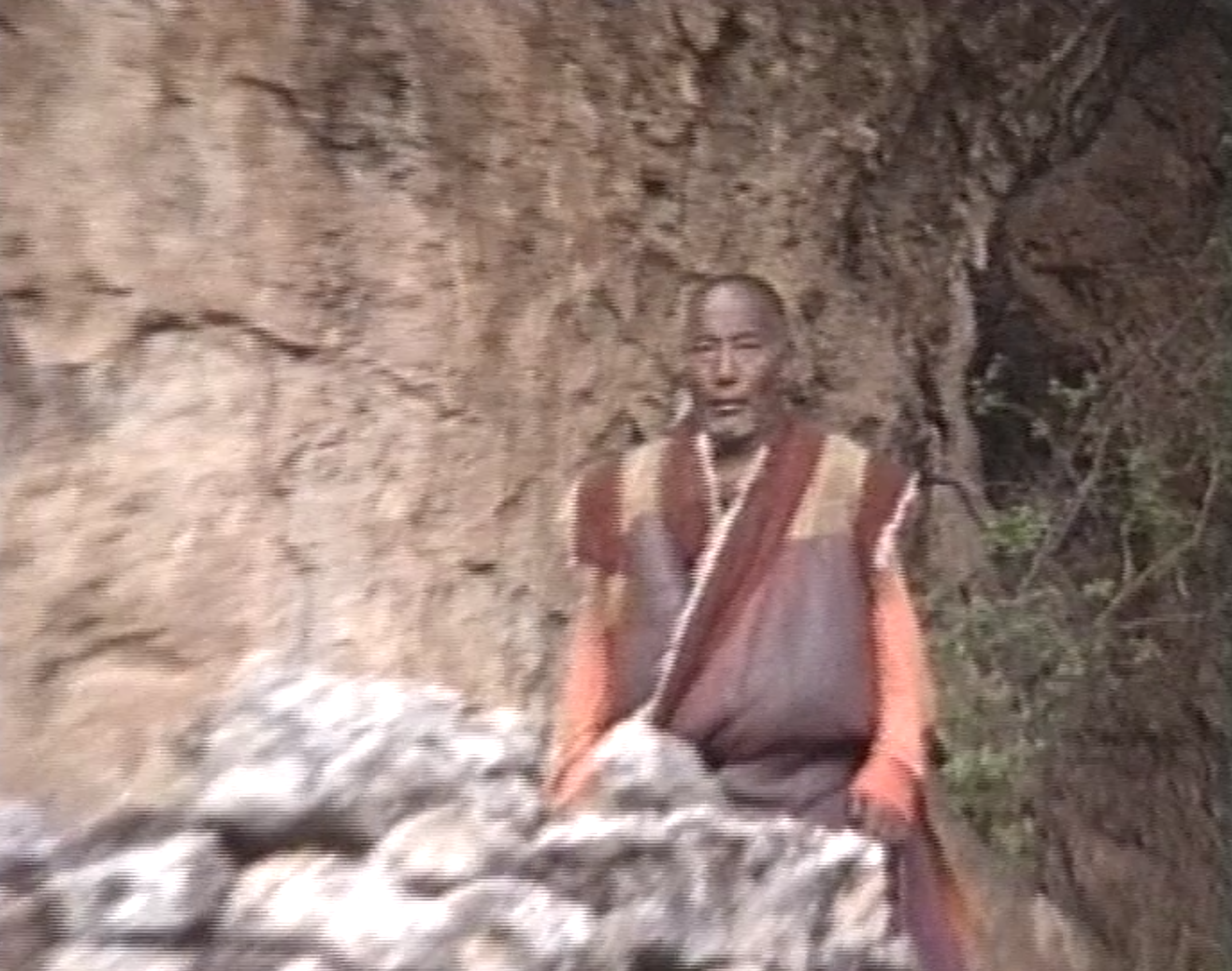

One day, together with him I meet a little man with a completely shiny head. He had come down from his refuge for just one day for the great ceremony. He usually lives in one of the caves near the village, where Changchub Dorje practiced for many years. I find him on one of my hikes on the mountain in front of the wooden door that closes the entrance to his rock hewn shelter. It is his retreat place and he invites me to visit.

He is very friendly straight away, but his clear eyes have a depth of sadness and detachment. I am afraid to disturb him in this rock hermitage of his, poorer than a Franciscan monastic cell, but the old man insists. He has a hint of a smile and with clasped hands indicates the carpet to me.

The hermit monk who Raimondo meets on one of his walks, standing in front of his mountain cave.

The interior is completely dark, the furnishings non-existent. I make out a small altar, a chest, his food bowl, a sack of barley flour, and the thermos from which he pours me some butter tea. As my eyes adjust to the darkness I observe his old-childlike face, while he shyly keeps his gaze fixed on the floor of the cave, covered with rough wooden planks.

In the silent dialogue I think I feel the deep connection between the old man and the mountain, like a child in its mother’s womb. This condition of his seems to reassure him, but who knows what his path was before he locked himself in here. I finish my tea and look around. Deep down, I get the impression that the hermit is also a custodian of the place, one of the many scattered in the thousands of caves of this mountain that is full of life.

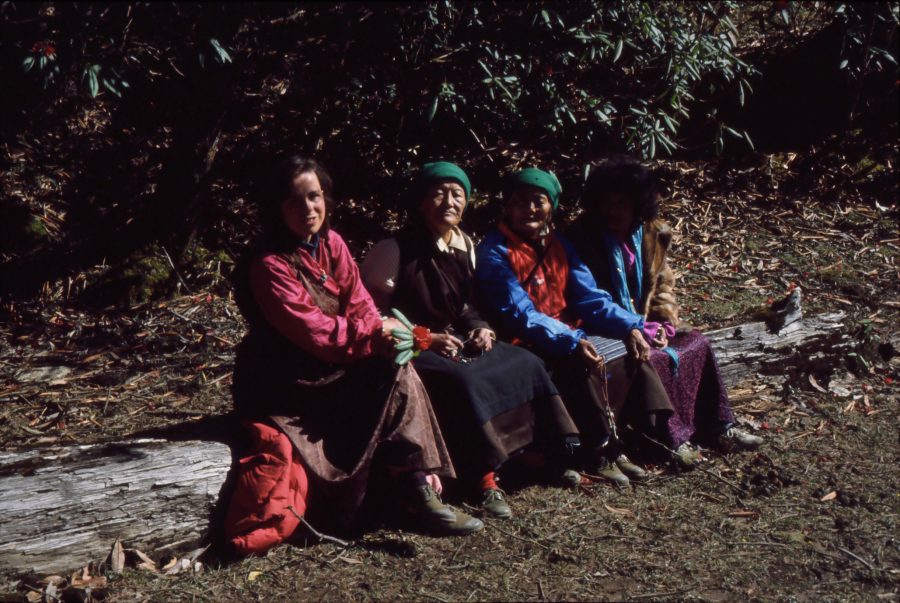

Yogis from the caves who have come for the ceremony with Rinpoche.

Some Advice About the Practice

The time for our departure is getting closer and all the lamas, monks and yogis are multiplying their visits to Namkhai Norbu. Each one of them asks for advice about his or her practice, as they did when Changchub Dorje was alive. I insist at length on knowing at least one of the texts that the lama has transcribed, and eventually I manage to get a translation of some verses dedicated to a lama by the name of Pema Loden, which I have reworked in Italian, unfortunately eliminating the original poetic meter.

“In the Dzogchen teaching it is always said that with regard to the way of seeing, there is nothing to confirm; with regard to meditation, no object to meditate on; and with regard to behavior, no conduct to be observed.

But, even if there is nothing to confirm, the way of seeing must be beyond limitation; even if there is nothing to meditate on, meditation must be non-distraction; even if there is nothing to observe, conduct must be free of affectation: this is the secret of the way of seeing, meditation and conduct. The three aspects of tawa, gompa, chöpa.

The different experiences are like flowers in a field in summer: they do not deceive, the beauty of their colors is true; thus in the dimension of pure presence, which is like heat and moisture, the play of one flavor is wonderful.

Similar to the state of rigpa, different shapes, different colors, single heat that governs everything.

For a practitioner living in this state, any action of body, voice or mind becomes part of the continuity of self-liberation.

If this is not the profound Ati teaching, what on earth can be?”

Namkhai Norbu quotes here the text of some Dzogchen tantras of the so-called “mind cycle.” The “way of seeing” is not the “point of view” and does not presuppose someone who is observing or judging. The origin of all problems lies precisely in the subject looking at the object and believing it to be something external. We all live in this continuous dualism and cannot help it. Our eyes look outside, our ears receive sounds from outside, our hands touch, our nose smells odours. An untrained mind is so conditioned by the senses that it automatically behaves in the same way even during meditation, which requires concentration on an external object, and hence the action, the effort of the meditator.

Yungton Dorjepal, a Dzogchen master, was asked what kind of meditation he practiced. “What should I ever meditate on?” he replied. “So you Dzogchen practitioners don’t meditate?” he was asked. He responded, “When am I ever distracted from contemplation?’ The significance of his answer lies entirely in the difference between gompa, “meditation,” and tingedzin, “contemplation.” In the former, there is an assumption of an object to meditate on or a thought to create. In contemplation, on the other hand, there is no distinction between subject and object, there is nothing to be done or created; one is in the unique and unchanging condition of origination.

Meeting with Changchub Dorje

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu films the courtyard of Changchub Dorje’s residence at Nyaglagar in 1988. Courtesy of the Merigar Archive.

We are now close to departure, and the meeting occurs almost by surprise, during a walk with Namkhai Norbu, Karwang and the lama who looks like Marlon Brando. As we arrive in front of Changchub Dorje’s house, his grandson opens the outer door, closes it behind us, and we are in the courtyard. The mountain is just above us, the village at our feet. Karwang enters the great lama’s room first, and no one speaks. It almost seems like a clandestine meeting, and in some way it is, considering that most of the inhabitants of Nyaglagar still don’t know the secret that has been concealed for so long to prevent the Chinese authorities from finding out.

Karwang lifts the lid of one of the two crates that are on the floor. It is very dark and I cannot quite make out the shape that we glimpse inside. I can hardly breathe now I know that that it is Changchub Dorje’s body and I don’t dare to get too close.

Karwang moves some of the salt that fills the crate with his hands. The head, on which some hair is still attached, is now quite visible, despite the darkness. I almost have a feeling of mental emptiness, and out of respect I bow as is the custom in Tibet, until my forehead touches the crate.

We all remain silent for what seems like an interminable time, then I see Karwang take some threads of fabric from the lining of an old leather cloak and hand them to Rinpoche, who in turn passes them to me, advising me to guard them. “Changchub Dorje,” he tells me, “left instructions to preserve his body for the benefit of all beings. Everything that has been in contact with him is charged with his energy.” I raise the gift over my head in thanks and go back to observing that body in semi-darkness. I never imagined I would see such a thing. It is like an embalmed corpse.

The crate is not very high, but it is the custom of tantric practitioners to die in the so-called “lotus” position of meditation, and with the last practices their body shrinks. I am reminded of his master, Nyagla Pema Duddul, who realized the body of light, just like Togden, Namkhai Norbu’s paternal uncle who had masters in common with Changchub Dorje.

My head begins to buzz, Namkhai Norbu and Karwang speak in low voices. We are alone in the silence of this shrine, and I finally have the real understanding of the great honor that has been bestowed upon me.

Raimondo and the remains of a small temple abandoned during the Cultural Revolution near the caves of the yogis.

l–r: One of the grandsons of Changchub Dorje in a bright yellow jacket, Phuntsog Wangmo, Rinpoche’s sister, Sonam Palmo, Karwang and a younger grandson of Changchub Dorje.

The Gifts of Departure

We are now on the eve of departure. In the evening, as is to be expected, a large crowd gathers in our room. It is time for farewells and gifts. Namkhai Norbu is offered a statue, a sacred text and a bell, symbols of the body, voice and mind respectively. It is the most important offering of a disciple to the master who introduces him to the “state,” placing his three levels of existence in the service of the received teaching.

I do not expect gifts when – one by one – Changchub Dorje’s grandchildren come toward me with medicine, relics and money. It is a wish for a good journey, an invitation to return. After them, more money, from monks, lay people, and nuns. I am moved and have nothing to donate in turn, travelling only with my clothes and the bare minimum.

I think the only way to give back something is to write about a world, this world, where my civilization can still find forgotten spiritual values and places of unspoiled nature. Unfortunately, it is not Eden, because here, too, the violence and ignorance of men has left its marks: the abandoned and crumbling monasteries, the victims of the Revolution, the children without schools, the people without hospitals or roads connecting with the rest of the world.

Perhaps isolation is for preservation, but those who want to remain outside the world, like the hermits of the thousand caves, should be able to decide that. Instead it is imposed by law.

It is now late at night. By the dim light of a single candle Namkhai Norbu writes the last pieces of advice for practice for those who have requested it. There is an exciting atmosphere in the air that keeps me awake observing the dark room, the altar by the lama’s bed lit by butter lamps. The dogs are, as always, masters of the darkness until the loud, steady sound of the drum breaks their barking, sending it to die out in the echo of a distant valley.

A few hours of sleep, departure at dawn. The last group photo is under a chorten, before crossing the wooden bridge to the main road. We are already on the horses when more than 100 people appear in the small clearing along the river. They offer khatag and silently watch us leave. From a hilltop across the river a group of boys wave their arms, while columns of sang smoke rise here and there greeting the departing lama.

I would like to imprint in my mind every rock, every color. I watch our colorful caravan, led by very young Khampas with long hair tied up in red and black threads. They wear white shirts, or colorful ones, and every so often they gallop off to catch one of the mules running in the wrong direction with its load of baggage.

Return to Derghe – Dimensions Beyond Time

Summer is now at its peak and everywhere the meadows are full of flowers, especially along the riverbanks. “It’s hard for the Chinese to spoil this land,” we comment with Namkhal Norbu, finding ourselves thinking the same thing in front of the display of intensely colored nature.

Along the road it is now easy to encounter the tents of the nomads camped in the open valleys, no longer afraid of the icy winds of the winter just past, and many families, friends and acquaintances have formed communal encampments with hundreds of yaks grazing on the now verdant meadows. Twice, before we find the jeep that will take us back toward Sichuan, we stop to accept the nomads’ invitations. We eat beef jerky and drink butter tea without talking.

We observe the smiling faces of the adults, the curious and shy ones of the children, their animals around the tents. To mark the rhythm of these lives, there is nothing but the light of dawn and the darkness of evening, nor is there any calendar beyond that of the seasons. “Is it not the concept of time,” I ask Namkhai Norbu, “that separates East and West? Have we not gone too far with the division into hours, minutes and seconds?”

Rinpoche, as often in such cases, does not answer. He points to an invisible point toward the valley, and in complete accord from who knows where a melodious and very slow Tibetan song arises. I remain listening in silence and this time I ask for nothing, not even the translation of the lyrics.

Read Part 1 Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Chengdu

Read Part 2 Background to travels in Tibet

Read Part 3 Derghe and Galenteen

Read Part 4 From Galenteen to Gheug, the master’s birthplace

Read Part 5 On the Road to Nyaglagar

Read Part 6 The Master’s Master

Read Part 7 Waiting for a Miracle

Read Part 8 The Mamo Cave

Read Part 9 Consecration of the Chortens

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988