The Master’s Master

Raimondo Bultrini continues the account of his travels with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet in 1988. They have just arrived at Nyaglagar village, residence of Rinpoche’s root teacher.

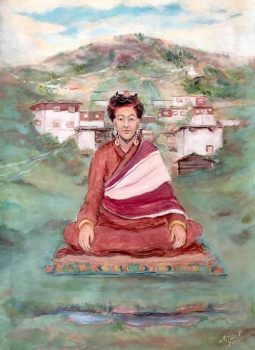

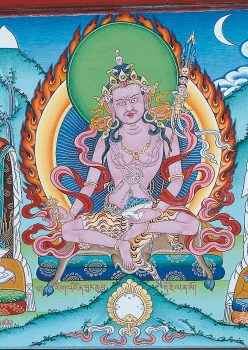

Changchub Dorje painted by Wilvin Pedersen

Changchub Dorje said he was 72 when he first arrived in the Gonjo region. He lived here in a monastery for three years before meeting his first wife and, with her, perhaps around 1920 (Tibetans often have a very approximate concept of time), he moved to this valley.

He had four children and then took another wife. His oldest child, Jurmed Gyaltsen, died before the Cultural Revolution, while the second, Atalamo, to whom great spiritual achievements were attributed, lived until a few years ago. The third, a monk and scholar, died at a young age after returning from a long trip to western Tibet. His last child, Mikyod, born from his second marriage, met a cruel fate and was killed by revolutionaries.

His three grandchildren, who are now [at the time of writing] between 30 and 40 years old, were born to his second child, a daughter, and to Mykyod. But the mystery of Changchub Dorje’s age is only one aspect of the complex figure of this village chief who is credited with the ability of far more famous realized beings, such as Milarepa. In particular, Changchub Dorje was considered to be a great doctor who understood the healing properties of every herb and mineral in these areas. It was most likely due to the special characteristics of Nyaglagar that the lama decided to interrupt his pilgrimage and build a house at the foot of these mountains where there are natural caves everywhere, water is in abundance, the vegetation rich, and the soil fertile.

He immediately discovered a “terma“, a treasure of great value, in one of the caves that are wedged right into the heart of the mountain overlooking the village. It was a claylike red earth that quickly solidified in contact with the sun. He began to learn how to use it to make protective objects such as the tsa tsa that Namkhai Norbu gave me at Galen and, combining it with the infinite variety of plants that grow spontaneously there, for his famous medicines.

Changchub Dorje had neither studied medicine nor Buddhist philosophy but he dictated to his disciples – including Namkhai Norbu, who was his assistant for many months – hundreds of pages, taken from dozens of volumes. “When he visited the sick – Rinpoche recalls – he was able to interrupt himself for hours and, on his return, carry on dictating from the same point. When I reread my notes I was surprised to find that there was no repetition, no gaps in logic.”

Accustomed in college to analyzing and debating, storing information and transforming it into philosophical concepts, Namkhai Norbu also had a certain idea about religious practice. Like all Tibetans he had received formal initiations, and as a young scholar he also knew by heart the ritual texts, the mudras, the symbolic gestures, and every detail of the ceremonies used to transmit the secrets of the Teaching from master to disciple.

Changchub Dorje came from a completely different background. His root teacher was considered to be a kind of madman. He had lived most of his life as a hermit and his disciples – including a woman disciple, Ayu Khandro, who lived more than forty years in the dark – received the transmissions in a very simple way, in a cave, using few words, according to ancient custom.

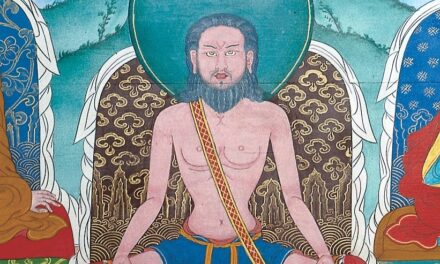

The “mad” teacher was called Nyagla Pema Dündul, and he was not strictly linked just to Buddhist teachings. Much of his training was in fact Bon. He had learned through very ancient practices how to be in touch with the elements of nature and to integrate his existence in the state that the masters call “contemplation”.

Nyagla Pema represented some of the synthesis of those traditions of both Bon and Buddhism labeled under the name Dzogchen, which means Great Perfection, and which indicates the condition of the individual, existence as it is, without concepts or limitations.

If Nyagla Pema was wild and unaffected, Shakya Shri, another of Changchub Dorje’s principal teachers, was very open and amenable. He became famous in much of Tibet for these qualities. Changchub Dorje came to him following a dream and stayed with him for a few years. As soon as he had received the essential teachings on the nature of the mind from Sakya Shri, Changchub Dorje became a disciple of Nyala Rangrik, the future head of the Nyingmapa school, known as the school of the ancients, the one most linked to the tradition of the exorcist Padmasambhava. Nyala Rangrik was chosen after a long discussions within the sect, as the lineage had been interrupted in the troubled era of the 13th Dalai Lama.

The Rainbow Body

In the meantime Nyagla Pema Dündul – his biographers recount – had realized the “rainbow body”, dissolving his physical dimension into the nature of the elements after years of practice. His disciples had assisted him until the day he retired to a small tent and ask not to be disturbed.

Two weeks passed, during which some strange atmospheric phenomena took place at the top of the mountain where the master was. After waiting for a reasonably long period of time, they all went to see what had happened inside the tent. Changchub Dorje and the other disciples found only his clothes, hair, toenails and fingernails, which are considered to be the only impurities of the body and as such impossible to dissolve.

This phenomenon has many precedents in the Tibetan mystical tradition. According to the masters, the breakdown of the elements takes place through the daily practice of the body, voice and mind. They consider the physical body itself and external objects the fruit of mental illusion, without form and substance, manifestations of a karma – accumulated in past lives – which produces human vision in the case of a person, for the deities, animals and other beings their respective dimensions of existence.

When the mind comes to full awareness, it breaks down the elements into their natural state, atom by atom, and any type of dualism, any difference between us and everything else dissolves.

Another master of the Nyaglagar lama called Shardza Rinpoche, who lived between 1859 and 1935 and practiced Bon Dzogchen, succeeded in having the same realization. According to other Lamas I met on my return to the West, Atalamo, the daughter of Changchub Dorje, also obtained the rainbow body, however, during my stay in the village, neither her relatives, nor Namkhal Norbu, told me anything about it.

The same realization was attributed to one of Rinpoche’s uncles, the brother of his father. His name was Togden and he had lived much of his life in mountain caves. The story I recount here was told to the lamas by a Tibetan officer who had been Togden’s guard during the Cultural Revolution, around the mid-1950s.

The yogi had been brought down from his caves to keep him under house arrest in a small hut near Derghe. One day the officer came into the room to check on the prisoner and found his body shrivelled up as small as the body of a child. Surprised by his discovery, and above all frightened by the imminent reaction of his superiors – who could accuse him of complicity in an escape – he ran to call the authorities from the provincial capital. But a few days later, after arriving at the hut which was closed from the outside, the soldiers discovered that nothing remained of his body but the impurities.

The officer managed to escape and did not want to know more about politics. He took refuge in Nepal to receive teachings from some exiled Tibetan teacher and here in 1984 he met Namkhal Norbu, who came to know about all the story.

A Game of Mirrors

Changchub Dorje by Drugu Chogyal

Changchub Dorje began to practice the teachings of his masters in many of the caves that are part of the village today. He came here following a particular intuition that distinguishes a person who is capable of seeing beyond the physical dimension. He felt that Nyaglagar was a “place of power” and that in this particular place in Tibet he would be able to continue to practice and bring to fruition the teachings he had received. His choice brought about great changes, not just for himself but for the disciples who followed him.

I started to wonder if there wasn’t some sort of game of mirrors in the personal history of these masters. In different historical circumstances each of them repeats a common achievement, that is, the transformation of the realities with which they come into contact. But it’s not a visible change. The places remain the same, with their stones, trees, rivers, and people do not change their faces or characters.

It is not even a question of the laborious cultural feats of learned pandits who import new ideas or literary forms into foreign countries. In Tibet this game of mirrors seems to start from the person everyone considers to be the forefather of the new Teaching that came from India, namely Padmasambhava. It was a pandit called Shantarakshita, a great scholar of Nalendra, the most famous university in the Buddhist East of the time, who advised King Trisong (8th century AD) to invite Padmasambhava to Tibet.

And, as usual, it was half history and half legend that have brought us those events that took place so long ago. In short, Shantarakshita – who was first invited by the Tibetan king to spread the principle of Buddhist compassion in the Land of the Snows – was rejected by the brutal reception that the Bonpo of Lhasa gave him. Among other things continuous storms were unleashed on the royal palace, and, according to the Bon shamans, the fury of the elements clearly manifested the anger of the gods against the new false doctrine.

In any event, Shantarakshita packed up and returned to India. “Only a great exorcist – he said to the king – can fight these demons” and he mentioned the name of Padmasambhava, who demonstrated his powers even before arriving at the appointment with the anxious sovereign.

The spirits of the waters, of the sky, and of the earth, who tried to create a thousand obstacles as soon as he crossed the Himalayan border, were subjugated – as hundreds of tales handed down by oral and written tradition tell. For this feat Padmasambhava used the strength of his own mind and a series of magic spells comparable to alchemical formulas for the transformation of matter.

At the invitation of the king he created monasteries, schools, and brought together a group of trusted disciples who spread his teachings to every corner of Tibet. The spirits and deities that had been defeated in the magical duels became his allies and served the Dharma, so that it was not necessary to replace all the previous figures created by Bon. On the spiritual level everything remained perfectly and apparently as before, even if on the worldly level the transition brought persecution and violence perpetrated in the name of religion.

Lama Changchub Dorje was the the twentieth century Padmasambhava of this valley, just as many of his disciples (including without doubt Namkhai Norbu) transformed other realities in their turn.

At first, the Nyaglagar lama had no intention of becoming some sort of village chief and in fact spent much of his time in the caves. But the old and the new disciples soon became a large community and many wished to limit themselves to meditating quietly, imitating the

master, with complete disregard of how to survive. It was this circumstance that prompted Lama Changchub Dorje to integrate the spirit of the teachings into practice.

Padmasambhava did not limit himself to using learned theological discourses to transform the religious attitudes of Bon, but mirrored the mentality of his time, fighting with the weapon of the exorcists of that level, the magic of the higher tantras. Similarly, the Lama of Nyaglagar found himself having to defeat the mentality and way of life of his disciples.

Since everyone followed him irregardless of he did, the master then went down to the small valley and began to cultivate the fertile land along the river. Soon the others did the same and thus a kind of agricultural community was born where the tasks were distributed equally as were the profits. And this was when Communism had not yet appeared in Tibet.

The First Teachings

In general, at the beginning the community of Nyaglagar was made up of poor simple people to whom lamas dressed in rich ceremonial clothes limited themselves to imparting blessings by reciting a few mantras at most.

Rigdzin Changchub Dorje as depicted in the Guonpa at Merigar

Changchub Dorje had grown up in the school of great masters, but he, too, came from a humble family and knew what his role was so that everyone could understand his way of transmitting certain knowledge. The Nyaglagar lama explained that religion and practice are not just devotion and prayer but life itself, experience accumulated without distraction day after day.

He then began to explain the simplest relaxation techniques, the basis for obtaining a mind undisturbed by the constant movement of thoughts. In order to put the instructions into practice more easily, some people continued to isolate themselves in the thousands of caves in the area. But many of those who had understood the principle of integration remained in the village, built houses for newcomers, worked hard, and developed their practice through habitual activities.

By controlling the regularity of their breath, keeping it stable and deep, they trained in concentrating their minds.

Walking and sitting with straight backs allowed the subtle energy to flow freely in all the channels of their bodies. With suitable food and drink they strengthened their bodies and favored the natural purification of the elements. By dissolving tensions, they avoided charging their existence with negativity.

This state of presence, of attention, could continue even at night. For Tibetans, sleep is similar to the state of the bardo, when all the senses – after death – are gathered in the subconscious level, and the ordinary mind, the one that judges and analyzes, no longer functions.

The ancient Tibetan Book of the Dead explains that those who have practiced through dreams in the presence of lights and sounds during their lifetimes, can also recognize the lights and sounds of the bardo, the state that follows death, an intermediate stage between death and subsequent rebirth, and will not be troubled by the frightening forms and the sensations that arise.

Changchub Dorje was considered capable of traveling in the state of bardo. He appeared in dreams to give teachings, just as he was able to manifest and reassure his disciples during those difficult moments, extremely conscious, which follow the blocking of the vital functions of the physical body.

It is a phenomenon that can also be explained intellectually, especially with dreams. Everyone experiences visions when falling asleep. Freed from physical hindrances, the stimuli of everyday life are transformed into more or less symbolic dreams that also involve other people.

A student who is particularly interested in his teacher’s lectures could, for example, revise them in the subtle state of dream consciousness and understand a meaning that may have escaped during school time. The teacher himself could perhaps appear as a father figure who takes the student by the hand and accompanies him or her to unknown places.

A spiritual master, such as Changchub Dorje, cultivated an even more powerful charisma over his disciples, and became, in ordinary life as in that of dreams, an irreplaceable guide. When the teacher is not physically there, it is the strength of his Teaching and of his example that guides the actions of his disciples. In the East they talk of the Guru’s mind in this regard, and it is a principle that has no equivalent with us in the West. But even when the disciples of a great philosopher or man of letters refer to the teachings of their master, they somehow follow his logical methods, through intellectual paths.

Contact between teacher and disciple in the East does not take place only through lessons, study or books. The three levels of existence according to Buddhism are those of the body, voice and mind. Thus, between master and disciple, knowledge is transmitted from body to body, from voice to voice, from mind to mind. It is an uninterrupted flow of lights, words and sensations.

To get in touch with his or her spiritual master, the disciple uses one of the methods he or she has learned: movements of the body, sounds (mantras) for the voice, visualizations for the mind. This is what is called Guruyoga: Guru means “master” and yoga means “union”. The “union with the master” is in fact the indispensable condition for having access to the spiritual knowledge already acquired by the Guru, and which no book alone can transform into direct, concrete experience.

To be continued in the March 2023 issue of The Mirror

You can also read this article in:

Italian