Waiting for a Miracle

Raimondo Bultrini and Chögyal Namkhai Norbu spend some time at Changchub Dorje’s place of residence, Nyaglagar, also known as Khamdogar, situated in a remote valley in Konjo in eastern Dege, and meet his grandsons.

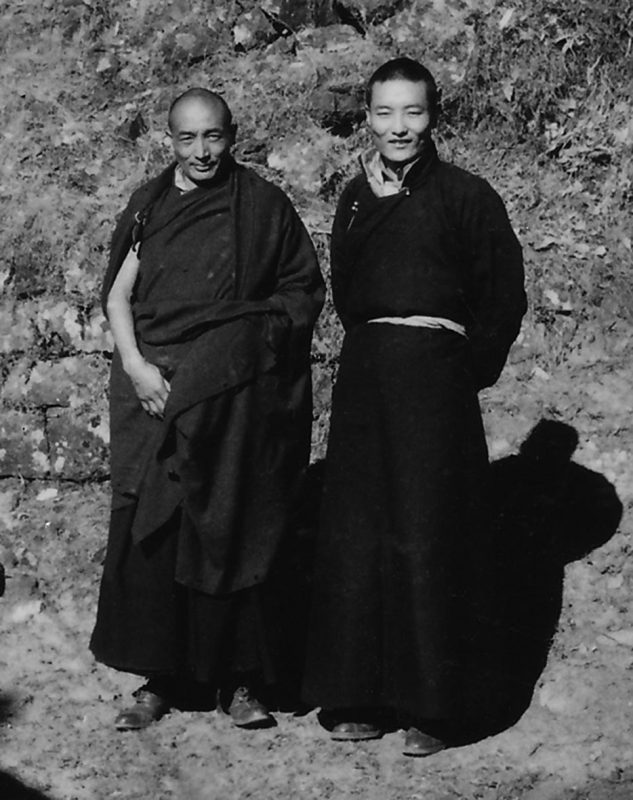

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu wearing a Padmasambhava mantle that belonged to Changchub Dorje assisted by Po Jo. Originally published in Il Venerdi di Repubblica, an Italian newspaper magazine.

Throughout the trip I theorize and practice many methods to experience these unknown dimensions. Nyaglagar seems like the perfect place to satisfy my desire to know. If Changchub Dorje is really that powerful, I tell myself, sooner or later he will manifest, perhaps in the form of a vision, or maybe, who knows, as a vibration. At night I hope he will appear in my sleep, during the day I search the sky looking for special signs. I find myself in that Western frame of mind that goes from secular disenchantment to doubt, from skepticism to waiting for a possible miracle.

Since, of course, nothing happens, I’m continually falling into a deep crisis where I question my whole self, the true meaning of travel, and what I’m looking for. When these moments arise I usually happen to find myself near Namkhal Norbu, who, after visits and teachings, spends all his free time reading his master’s texts in a low voice, as if reciting them.

Sometimes I have the distinct feeling that Rinpoche can penetrate my thoughts. One day he raises his head, looking at me with a friendly smile, and asks, “What’s up?”. I don’t have the courage to speak openly about everything: “I was thinking about the great fortune I have to be able to stay here” – I reply – “but I can’t do anything to deserve it: I don’t speak the language, I don’t understand what these people are saying, I just sit here for hours without being able to communicate”. Rinpoche continues reading his book and jokingly declares the subject closed, freeing me from the weight of thoughts that I can no longer control: “Those who are fortunate have absolutely nothing to do,” he says.

A few days later, overwhelmed by this anxiety again, after hours and hours of solitude and silence, I think about negating all of my previous fantasies and theories on the wisdom of oriental philosophies, all my self-convictions on the power of Buddhist divinities, on the principles of the energy of yoga, on the Teachings, on the teacher. After all, I suppose that the familiar figure of Christ, as an example of a compassionate man, is more than enough to satisfy all my spiritual needs.

The more I meditate on this, the more I feel a kind of pride in the uniqueness of the Christian message, even in these mountains where the figure of Jesus is almost unknown. Sitting on my carpet with a cup of tea and gazing into the valley where the sky alternates rain and clear spells, I suddenly hear Rinpoche’s voice: “What are you meditating on?” he asks.

Once again I feel practically naked, discovered in my innermost thoughts. It seems impossible to me that he can read them like an open book, but this is the immediate feeling I have. I have never experienced it before and it is precise, clear-cut, unmistakable.

I don’t answer immediately, in the embarrassment and surprise in which I find myself. “I was reflecting on pride, – I limit myself to saying, awkwardly hiding everything else – thoughts come one after the other. It is easy to get carried away by what passes through the mind”.

“Pride – Rinpoche tells me – when it is recognized as the origin of negative emotions, can be self-liberated, dissolving the tension that is its consequence. Because when pride, like jealousy, envy, anger and any other passion, is not governed by presence, it hinders knowledge of the true nature of things.”

“But when thoughts disturb you, like flies you can’t chase away – I insist, now pretending that this was really the only object of my reflections – how can you have this presence?”

“Where do thoughts come from? And where do they go? Try to look…”

“I have no idea, really. I don’t think they come from a specific place.”

“It’s not enough to analyze, you have to experience in practice. Only after that can you say: ah, here, I found them, or no, I didn’t find anything.”

I finish my tea and go up to the cave where Changchub Dorje taught and where I discovered the special red earth with which he made tsatsas [ed. stamped clay figures] and medicines. I stop in front of a throne made of rock used by the master during his teachings and try to empty my mind, letting it simply follow the rhythm of my breathing.

I know theoretically that the rule of good meditation is to observe thoughts as they pass, not to dismiss them. They are like birds that leave no trace in the sky, and there is no need to follow them or stop to look at them. The Master said to observe the point where they arise and where they disappear, but I don’t even notice the moment where one thought ends and another begins. I have to concentrate better. Ah, a new thought comes to my mind, and here’s another and another. I haven’t the faintest idea where they come from, but I feel much more relaxed.

Unfortunately the feeling does not last for long. In some corner of my mind there is a recurring thought, the wish to receive a sign from this place that everyone says is magical and full of power.

It is an idea that grows and comes before all others. “I don’t have to make the situation worse – I tell myself – I have to make it go away”. But it doesn’t go away and even when I have the impression that I have succeeded, after a while it reappears. Then I begin to sing the mantra that Changchub Dorje himself transmitted to Namkhai Norbu, the Song of the Vajra, that was taught to the monks of Galen.

I concentrate my senses only on the vibrations that the sound produces inside my body, and the tensions dissolve in internal space, bringing my mind into a state of stillness in which everything seems to remain suspended, motionless. Suddenly, like a fish leaping out of the water, comes a thought, a sound. It passes, and for an instant it does not disturb the peace of this state. It is the sensation of a moment, the fleeting experience of something that could and should last throughout every moment.

I walk back past Palden’s house; he is the youngest of Changchub Dorje’s grandsons. The living area is on the second floor of the building where a large temple which has remained almost intact is located. I climb the wooden staircase to reach an open gallery with a single large room where I find Namkhai Norbu together with Sonam Palmo, Phuntsog, and many members of the Nyaglagar lama’s family.

Mikyod’s death

Rinpoche, Palden, Changchub Dorje’s youngest son, and Po Jo.

It is lunch time and we are seated behind the low painted benches where the food offerings are placed. There are many thangkas hanging on the walls, some of which certainly depict the master. One in particular is striking for its beauty. The founder of Nyaglagar is depicted as a dancing yogi, and beams of colored light of hypnotic intensity radiate from his body. Underneath is an object that looks like a paper lampshade, but is actually a cylinder that continuously rotates without any mechanism. Simply with a small initial push it is able to take advantage for a long time of the right inclination and the speed acquired. It is a device that is used to rotate the mantras written inside, and hence to make the “wheel” of the Teaching move symbolically forward.

It is the same principle as the small prayer wheels with the mantra OM MANI PADME HUM that the Tibetans hold in their hands and rotate clockwise for hours and hours, or the very large ones in the temples that are also moved by the faithful. The significance is the same as that of the prayer flags that are exposed to the wind to offer the benefit of sacred words to spread in every direction through the most mobile element of creation.

The food in Palden’s house is plentiful, with plenty of almost melt-in-your-mouth dried meat. I begin to recognize the best bits so that I avoid cutting the ones I can’t chew. The meat here is softer than in Galen because we are at a lower altitude and the climate is not so dry. The taste is also better, but it doesn’t keep as long.

I realize that with this diet it is almost impossible to eat distractedly, forgetting, for example, that you are feeding on an animal. The strip of meat is as hard as stone and on contact with saliva softens and releases the animal’s blood. It’s a sensation of heat, of tense nerves, of life flowing back into that piece of yak. Tibetans mentally recite a mantra for the benefit of the being that is feeding them and believe that the right intention, authenticated by the appropriate mantra, will produce a spiritual cause for its next, better rebirth.

During lunch, as a sign of great respect, the “capala”, the skullcap of the skull of Mikyod, the son of the master killed by the Chinese, is brought to Namkhai Norbu. Rinpoche turns it over in his hands and translates the story that the old monks tell him. Mikyod, who lived in a nearby village, was to be taken by the military and tried as a counter-revolutionary. But he didn’t want to follow them to go into a concentration camp or prison, and so he ran away towards the forest chased by the Chinese who started shooting at him without managing to hit him. However, all of a sudden Mikyod decided to stop; he sat down, took off all the protection cords from around his neck and was killed.

The revolutionaries arrived at Nyaglagar from Qamdo, they recount, but the village was too distant and tiring to reach, even on horseback. For this reason, only a few came and left almost immediately, without completing the work of destruction, as had happened almost everywhere around. They limited themselves to knocking down the tops of the chortens while leaving the foundations intact, to burning a few thangkas and the few books of Teaching left in the monasteries and homes. Most of the manuscripts were actually hidden in the nearby caves.

Just above Palden’s house is one of the libraries with hundreds of texts piled on top of each other. There are also the teachings of Changchub Dorje transcribed by Namkhai Norbu more than thirty years ago.

We are invited to go up to a terrace where a large window frescoed with figures of masters sends beams of light into the temple. On the wall of an almost completely dark room figures of skeletons and large wild animals dance. It must be the room for the chöd, the ritual that is also practiced in cemeteries. I observe the macabre figures of the dance and think that basically every corner of this village, every moment spent here seems to impose a reflection on the constant presence of death.

Lama Karwang

The grandchildren of the founder of Nyaglagar give Rinpoche many writings from the library, among which are some small precious notebooks. They contain the advice that many lamas and yogis received from Changchub Dorje on how to improve their practice and explain how to learn, develop and stabilize contemplation.

A master knows precisely when a student is ready to take a certain step in his or her practice, even if there are apparently no signs of spiritual attainment. Changchub Dorje’s eldest grandson is Lama Karwang. Despite the relative power that comes from being the spiritual leader of the village, I see a simple man who is so silent and unobtrusive that he almost seems to walk on tiptoes.

Observing him, it doesn’t immediately occur to me that this simplicity could be the fruit of long inner practice. Karwang gives me a photograph of himself, very small, in which he sits cross-legged in a meadow, and he asks for one of me. I look at his photo for a long time, just as I study his movements during his repeated visits to our room, or as we stroll through the dusty streets of the village.

Perhaps I would like to discover the secret of his moving so lightly, without ever making a sudden, awkward movement, without an overly loud tone of voice. His face shows no anxiety or tension. He is serious, or else cheerful, but never worried or angry. Deep down, he seems to have the reactions of a child.

With an amused expression he really likes listening to my readings of the phonetic transcriptions of mantras. He often calls his brothers to witness the little marvel of those foreign signs that correspond to their alphabet, and he asks me to repeat them several times. He seems happy to hear me speaking Tibetan, and he doesn’t understand why, in addition to reading mantras, I don’t also learn to converse.

Another reason for regret is for not having been able to commit myself to studying this language. I’m sure Karwang would have a lot to teach me, and I hope that one day, if circumstances permit, he will be able to come to the West. Who knows if he could maintain the same seraphic calm when faced with the bureaucracy and smog, the clock and the computer?

According to Rinpoche, Karwang’s value also lies in his doctrinal and spiritual knowledge. The young lama has written many texts that seem to demonstrate a high degree of knowledge. It is not by chance that he is the most respected and esteemed of Changchub Dorje’s grandchildren. This is an acknowledgment which acquires greater value if we consider the uncommon qualities of the other grandchildren. In fact, they all have a truly rare quality of humanity and congeniality, they joke with everyone and are surrounded at all times by crowds of children who obviously love to play with them.

The Grandsons of the Master

The youngest, Palden, is 25 years old, with a broad face and robust build. My fondness for him is linked to a gesture that I had never seen in China or even in Tibet: I see him holding hands with his young wife. It may seem strange that something so normal affects me so much, but here I miss this expression of feelings of love that is so common in the West, despite the great gentleness and spontaneous affection of the Tibetans.

The other grandson, the second in age, is Po Jo, the son of Mikyod. He is about thirty years old, thin, with round eyes that are never still and a slightly receding chin. His appearance becomes very funny when he wears a round wool hat that accentuates the marked features of his face. His house is perhaps the busiest during our stay, because it is here that Namkhai Norbu gives teaching to the people of the village.

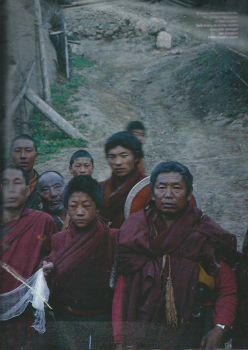

Monks from Changchub Dorje’s monastery at Nyaglagar and hermits living in the caves around welcoming Rinpoche.

Not everyone manages to get inside because the room is not large enough, with the two corners for the carpets taken up as usual by the benches for offerings and food, the wooden columns in the middle dividing up the space even more, and the upper area enclosed by large balconies where a bit of everything is stored. Pride of place goes to the altar, where many photographs are set out, including those of Namkhai Norbu and his son Yeshi, evidently sent by post years earlier, and thangkas and sacred images, especially of Changchub Dorje.

Surprisingly, tucked into a corner, I discover a large Chinese stereo radio. It is the only house in all of eastern Tibet where I have seen something like this. It is certainly not strange, because the towns that are inhabited by many Chinese are just a two-day ride away. But the fact remains that in my bucolic vision of Tibet these objects, including the watches that some khampas wear on their wrists, and even the grandsons of Changchub Dorje, seem to belong to another world.

Mikyod’s son is clearly in love with Phuntsog and spends many hours in our room courting her, unsuccessfully as far as I understand. For her – and consequently also for me and Sonam Palmo – Po Jo always brings candies, sweets and sometimes toasted barley seeds. He woos her by telling stories that I can’t understand, but which are definitely funny because the two women laugh a lot together.

It must be said that Phuntsog and Sonam Palmo don’t need to listen to funny stories to be in a happy mood. Except for moments of emotion for some particular situation, mother and daughter often joke around, and their relationship is like that of two teenage friends. They always walk hand in hand, in perfect harmony, so much so that in Chengdu I didn’t realize at all that I had traveled for many days together with Phuntsog’s real mother, with whom my young traveling companion had a much more formal relationship.

Po Jo immediately falls in love with this girl, and is ready to offer her his house, one of the most beautiful in the village, his stereo radio and anything else she could wish for. But Phuntsog doesn’t seem at all interested in getting married, and what’s more she doesn’t like Nyaglagar very much. She prefers Galen, and can’t wait to go back. So the young lay lama has to content himself with joking with her, and put up with the candid irony of Sonam Palmo.

To be continued in the June issue of The Mirror

Read Part 1 Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Chengdu

Read Part 2 Background to travels in Tibet

Read Part 3 Derghe and Galenteen

Read Part 4 From Galenteen to Gheug, the master’s birthplace

Read Part 5 On the Road to Nyaglagar

Read Part 6 The Master’s Master

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988

You can also read this article in:

Italian