Raimondo Bultrini continues his account of travelling in Tibet with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in 1988 arriving in Derghe, the highlands, and Galenteen

Towards Derghe

Returning to Asia from retreats in Japan and Australia, Rinpoche had passed through Hong Kong where he had been greatly struck by the opulence and business frenzy of the island, a model for the China of the future waiting for the concession of the British government to end in ‘97 to return it under the laws of Beijing after 156 years of governing. The master wondered if it would be possible for Tibet to follow the same model envisaged in Hong Kong of “A country with two systems”, but he feared the impact among his people of a model of industrial and commercial development based on the exploitation of the environment and resources.

The same morning that began with the noisy hotel alarm clock, part of the procession that had greeted us upon our arrival sat on the floor in our room and in Sonam Palmo and Phuntsok’s. They had opened large canvas bags filled with tsampa for breakfast and Rinpoche happily savored that taste from his childhood by showing me how to mix barley flour with butter tea poured from large Chinese thermoses into the wooden bowl that his relatives had given me to take throughout the journey, just like the nomads. Wherever the shepherds of yaks and dri (females) go, they bring one with them to receive the offer of tea from the various families they meet in their white tents during the summer movements of the herds on the highlands, and in the black tents made from animal hair that defend them from the Himalayan winter.

Raimondo Bultrini

That bowl in which tsampa and tea are mixed is a precious object and traditionally every Tibetan carries one in a pocket of his or her chuba. Rinpoche’s was carried by his sister or niece and mine was tucked into the inside pocket of an anorak and will be invaluable along most of the route in the less inhabited areas of the highlands, together with the dried yak meat that the relatives of the master had dried outside in the thin air of the mountains. It was just a foretaste because Rinpoche had been invited by the Sichuan authorities to a multi-course banquet lunch, and had to honor them by eating as much as possible between the many tankards of Chinese beer. It was his first close meeting with the state authorities who were to give their decisive opinion on his proposals for practical collaboration on the ground. Enlivened by the many dishes and drinks that included powerful Chinese liqueurs, they went so far as to question the master about his relationship with the Dalai Lama. Rinpoche told them frankly that the exiled leader was not an enemy of China as many imply, and he explained the meaning of the five political points of the agreement proposed by His Holiness to China.

He told them that each of these points is in line with the United Nations Constitution itself, also accepted by the Chinese Communist Party, and that the points that were presented should be discussed instead of dismissing them out of hand. Everyone could benefit from them, he added, and not even China could ignore the need for real autonomy not only for Tibetans but also for all other ethnic minorities. He concluded the conversation – which continued with several toasts – by saying that one of his main intentions was to preserve Tibetan culture and language before rapid transformation could destroy it. As we had the opportunity to see during our trip, there was in fact the beginning of Chinese colonization, the outcome of which is visible to everyone today. It was easy enough to understand simply by seeing the images of the felled trees transported by huge Chinese trucks that we encountered along the border roads, and the hundreds of trunks seen floating down the rivers that descended from the Himalayas destined for the large Chinese sawmills.

1988 was Rinpoche’s first full immersion in the places of his origin and of his education as a “tulku” or reincarnate. While it was easy for the master to understand what was happening in a country he had left before the full Chinese military occupation thirty years earlier, I could only count on my study of history and the experience of two journeys, a journalistic one in the two previous years in Beijing among intellectuals, and another as an assistant to a group visiting the tourist resorts of the south, always accompanied by official guides.

The master didn’t always have time to translate or talk to me about the kind of people and places we met, but he did his best using the common Italian language, as well as trying to teach me the basics of Tibetan using a game for children, a series of characters with the Western transliteration of consonants and vowels. He wrote them on a series of cards by hand, folded them with care and placed them in a Tibetan purse and asked me to take out one from time to time and memorize it. Unfortunately, I did not make much progress and this linguistic isolation often weighed on my mood and excluded me from fully perceiving the intensity of the dialogue that took place almost daily in front of my eyes between the master and the thousands of Tibetans who came to meet him wherever we found ourselves.

The still living fame of his predecessors and teachers went before him, but also the esteem of the scholars of ancient Tibet as could be seen. At times huge crowds gathered outside the houses, monasteries or tents that hosted us to see and hear him speak, mainly to receive at least a blessing. Rinpoche listened to everyone and for those who requested them he created small tokens for protection on the spot, most of the time using the same khatag received as a traditional offering of the “pure mind”.

One day, observing grazing nomads and real-life scenes that had not changed over the years, Rinpoche recalled something that had struck us at the University for the Minorities in Beijing. In the local annexes of the National Institute of Ethnic Peoples there was a small museum where Tibetans, Mongols, Uighurs, and other ancient populations were depicted with images and mannequins dressed in their traditional costumes with a model of their typical home in the background. “This is what Tibetan culture risks,” he commented, “becoming just a memory of an extinct people like the Vikings and the ancient Egyptians”. Rinpoche said, however, that faith in religion and in the ancient teachings would not disappear anytime soon among his people, since it had remained almost unchanged among a vast majority of his compatriots during the decades of communist rule. He was more concerned about the fate of the Rimed movement of unity among all Tibetan schools and the increase of false masters in the dharma business, capable – he said – of dividing the community of practitioners and contaminating ancient traditions and lineages that were centuries old if not millennia, both inside and outside Tibet.

Political power and the people

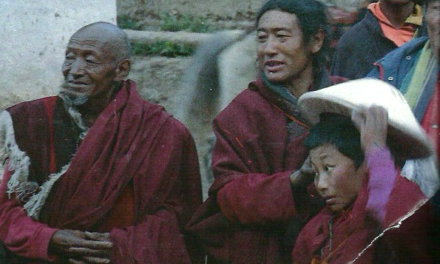

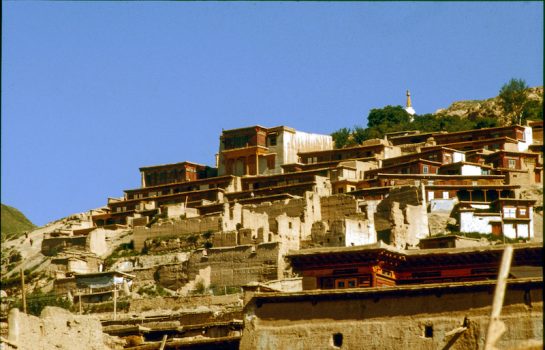

After several days of travel from Chengdu – the capital of Sichuan and the starting point for travellers to Tibet – we reached Derghe, the capital of the province of the same name where Rinpoche was born in the village of Geug on December 8, 1938 and studied with masters from various schools. I had left my job as a journalist for the newspaper of the Italian Communist Party to follow him in what I felt was also an “ideological” turning point, but I was pleasantly struck by the fact that the Chinese “red” authorities themselves shared the same esteem for the master as scholars and academics did. Rinpoche’s reception at Derghe’s oldest printing house of Buddhist texts was the foretaste of what awaited us in other villages and provinces. It seemed just like a scene from another era if it hadn’t been for the master’s anorak which strongly contrasted with the attire of the local Tibetans and the reddish purple robes of the monks who surrounded him. Rows of monks and common people with their hands pressed together were lined up along the entire path while the long ritual horns sounded on the roof and the smell of cypress sang mixed with other aromatic herbs wafted through the air.

The Derghe printing house

Rinpoche told me that part of the library had been destroyed and abandoned during the Cultural Revolution, as well as the Derghe Gonchen monastery of the Sakyapa tradition on which the printing of manuscripts depended. Many of his uncles and teachers had studied and taught here, in order to escape the strict and “commercial” rules of the monastery, which I will talk about later on. The printing house had maintained its fame and was now being restored to the satisfaction of pilgrims, scholars, and monasteries who commissioned texts of Buddhist canons and many other teachings that had been secretly preserved during the Cultural Revolution in the form of wooden matrices often centuries old. That same day the master was expected by the administrators for an official greeting at the assembly hall of the Derghe town hall, but it turned out to be a long and informal meeting with those officials who wanted to know his sincere impressions of Tibet after so many years. “You did well to rebuild monasteries, libraries and temples”, he told them, “but it would have been better in the first place to admit that it made no sense to destroy them. I think that now it is important to create the conditions so that we do not go back to destroying by doing something together. But we must be careful not to mix the two cultures. For example, among the city administrators today there are many Tibetans, but in the Chinese offices they cannot continue to speak their language. Much has already been lost, and much will be lost if one of the two cultures superimposes itself or mixes with the other.”

The Derghe Gonchen monastery

Our group led by Rinpoche had been placed near the mayor and his advisers, seated in Chinese style on the sofas arranged one in front of the other and divided by a table with cups of tea with lids to keep the tea warm. Along one of the walls the portraits of the fathers of Communism hung in a row, from Marx to Engels followed by Mao and Deng Xiao Ping, known for his economic reforms and the first openings to the world. On the other wall, and probably only for that occasion, figures of Buddhist deities had been hung.

Namkhai Norbu soon realized that he had struck his audience – there was a deafening silence – on a sensitive point in the relationship between political power and the population. He must have foreseen this circumstance because it was here that he mentioned his plan to decision makers for the first time: to build schools for Tibetans and in the Tibetan language in the areas where he had grown up and studied. After the meeting, a senior official of the local government who had been his friend during his years in China invited us to drink some wine at the home of a peasant family and solemnly promised to lend a hand to the master to put his ideas into practice. He was surprised when the wine seller in front of him asked for a blessing from the lama who had come from afar and the master threw some rice into the room.

In the evening of that intense day Rinpoche returned to his room satisfied with the promises he had also received from other leaders, but tired, and his tasks were not over. I have already said that Rinpoche accepted his treatment as a “lama” aware of the need not to disappoint people who were more traditional, including his own relatives who had called him Rinpoche since the day of his recognition. In fact, he knew that the arrival of an important tulku who was a disciple of many great lamas of the Sakyapa monastery of Derghe Ganchen, would bring crowds of Tibetans to ask for a blessing, filling the hotel corridor in silence, under the incredulous eyes of the Chinese guests. It happened very often at each stage of the journey and the small photo album that Rinpoche carried with images of himself, donated by various Western practitioners, was soon empty.

The presence of the Chinese became increasingly rare as we entered eastern Tibet, at that time still partly uncontaminated and without too many settlers, concentrated only in the mildest valleys, like the gold seekers we met bent over their sieves along the river banks in search of gold-bearing sands.

At the end of a tiring day that began with a premature wake-up call and ended with a crowded room, Rinpoche was kind enough to tell me a story that I associated with the man from Turin in search of a physical blessing, a brother of ours who was neither Tibetan nor even Western. “Once upon a time there was a bat who wanted to make birds believe that he was one of them. ‘Just look. I have wings, I go up and down and where I want.’ The birds believed him and let him fly with them. One day he met some mice and said, ‘Look. I’m just like you. Look at my muzzle, my teeth.’ But the time came that the birds and mice found themselves in the same place and they all realized that he was neither mouse nor bird and he remained alone.” “Now let’s sleep.” Rinpoche switched off the light and before going to bed reminded me about an important duty. “Tomorrow we have to change money.”

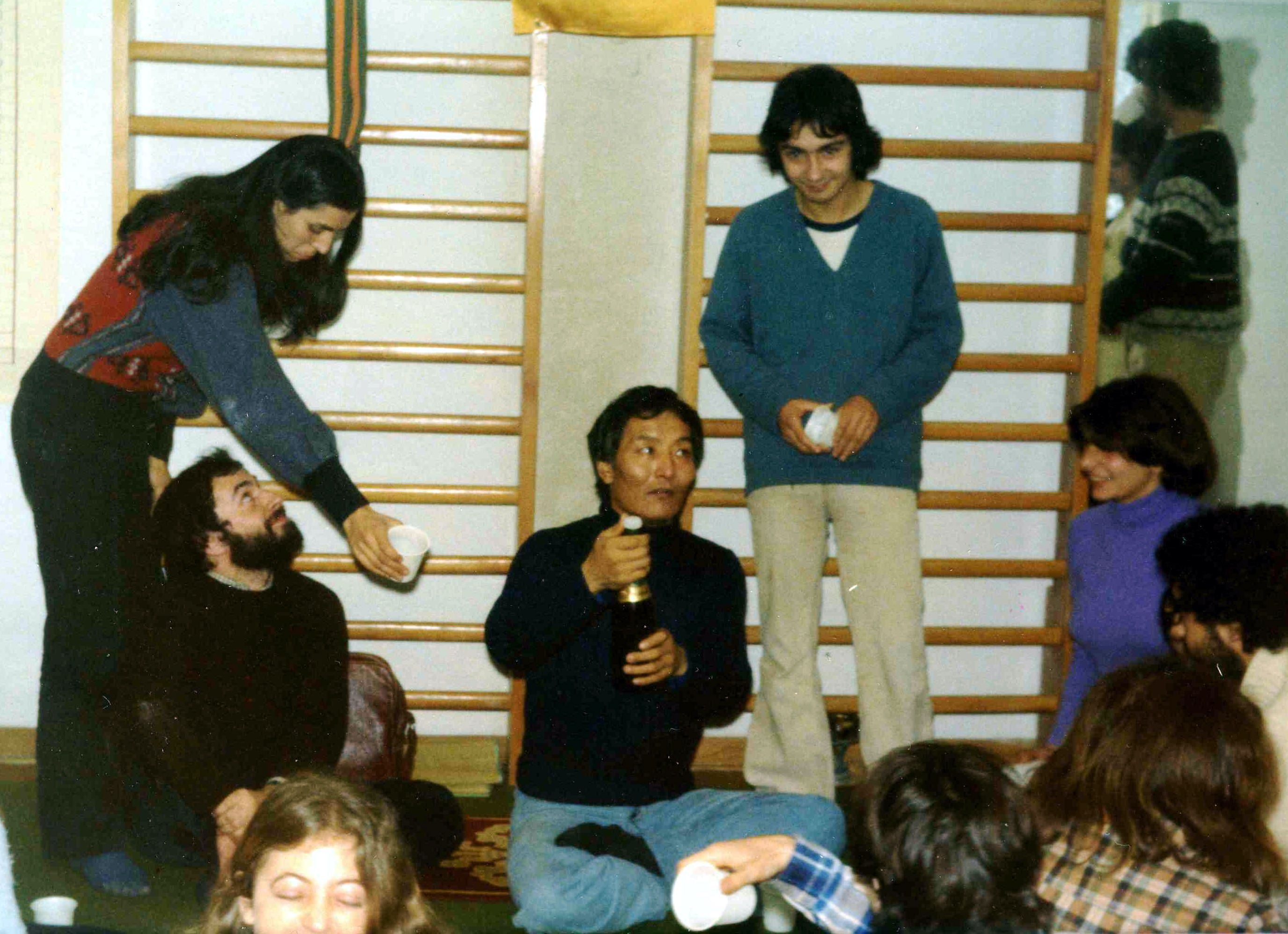

The situation with the currency was a delicate operation in a country where foreigners can only use FECs – certificates issued by the government at a high rate – which were almost unknown in the regions we would go to, where only renmimbi or yuan were used. Some people had come to Chengdu from various continents to meet up with us: the American, Alex Siedlecki (who intended to make a documentary and is current director of the MACO Museum in Arcidosso), Ady from the Greek community in Athens, who had come just to meet the master, and Keng and Cheh (now a yantra yoga teacher and SMS instructor) from Singapore. Keng and Cheh, as we will see, will also join us later in Derghe and their presence in Chengdu proved to be providential for the translations with members of the gang of money changers. We were made to wait in a hotel room for the phone call announcing the arrival of the group of men with cash tucked under their jackets and in their bags. They smoked and were very nervous because they wanted to take advantage of us, but we ended up making a good transaction even though they also managed to pass us a bundle of counterfeit bills. There were so many bundles of yuan that Rinpoche threw them in the air shouting “We are rich!”

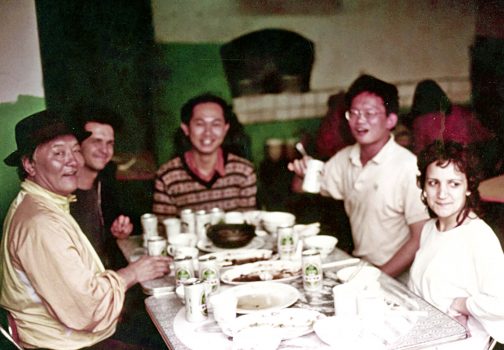

On the left Rinpoche, Alex Siedlecki, Cheh Goh, Keng Leck and Ady. © 2021 Namkhai Collection/MACO

In fact, if the money had not been destined to be donated to the sacred and not exactly profane places of the villages where schools and hospitals would be built, it would have made more than one Tibetan family rich for the rest of their lives.

Towards the highlands

On 11 May, a Wednesday, we left the group of foreigners who had not been able to obtain permits and began the journey towards the Tibetan highlands passing through some Chinese villages that were very poor at the time. There was a road block at the beginning of the first access road to the Qionglai mountains and we stopped for a night in the Chinese town of Ya’an, where the master had already stayed when he was elected as a delegate of the monasteries of eastern Tibet to participate in the inauguration ceremony for the Chengdu-Lhasa highway. He said that at that time the idea of bringing some progress to a country that had been isolated for millennia infected many young people and that even the Dalai Lama tried to get an agreement with the Communist authorities for a form of controlled development, such as the one he will present again many decades later in his Five Point Peace Plan.

While we were waiting in vain for the opening of the road, we noticed an old farmer’s wife selling hard-boiled eggs from a wicker basket. Rinpoche bought some for the whole group and soon other peasant women arrived but without the same luck because we returned to the city to wait for the reopening in the morning. The story of the eggs reminded the master of what had happened when the first Chinese troops arrived in eastern Tibet. “At the beginning the soldiers were very kind, and, for example, they bought eggs at a price even higher than their value and made themselves welcome by the people by fixing roads and paying for food in precious yuan. Unfortunately, that period did not last for long and soon they showed a much harsher face and made themselves hated by many.”

After crossing the first peaks of the Tibetan range, we reached Kangding where Rinpoche had many acquaintances among his former Chinese and Tibetan students of the 1950s. Before the official meetings, they came to pick us up to go to the sulphurous water baths where as a young man the master loved to immerse himself almost every day between one lesson and another, a unique enjoyment for all of us. During our days there the professors from the local university organized crowded lectures and helped arrange our travels to the “real” Tibet.

On the morning of his departure, May 14, Rinpoche had a dream. We had arrived in a mountain town where the people spoke an unknown language. I had driven the car in which we had traveled there and in the dream he imagined that he had walked away from the clearing where we were parked. Upon returning, he no longer found either the car or the group and began looking for us asking for directions from some people who, however, did not understand him. At a certain point, he came upon a path with several curtains and found himself in a beautiful country. “I forgot I was lost,” he said, amused.

In the real dimension, the jeep began to climb between panoramas that changed radically as we met the first Tibetan-style houses and the first yaks. Beyond the city of Garze, already with a Tibetan majority, we will tackle the highest pass of all, the Chola Shan. Rinpoche told me that a large number of Chinese and Tibetan workers had died to build this road that reaches 6000 meters and now many of the resources from Tibet travelled on trucks along that asphalt snake that we will see winding around breathtaking hairpin bends and valleys visible below the great precipices.

There were all the signs of the proliferation of increasingly gigantic and invasive public works that would alter the Tibetan landscape forever and we did nothing but meet lorries and trucks with trailers loaded with timber, especially pine and fir taken from upstream. Today we all know the effects of that deforestation, including the increasingly violent floods in Chinese cities also caused by the melting of large glaciers due to the greenhouse effect.

The master observed everything with stern eyes and during the trip in our jeep loaded with people and luggage he told me a paradoxical story about the old local administrators of a village in Derghe before the occupation. He said that a company famous in Japan for its soft and strong toothpicks had offered to buy certain trees from their forest to produce them locally, using only the core of the trunk and throwing away the rest. Fortunately, the local leaders realized that in exchange for a few yen it was not worth destroying an environment that was difficult to rebuild. But for more than 60 years, decisions have no longer been up to the Tibetan people and the havoc continues.

The ancient story of Galenteen or Galingteng

Before reaching Galenteen, which we would become our base for numerous expeditions in the most remote and sacred areas of the pilgrimage, Rinpoche told me about his uncle, Abbot Khyentse Wangchuk, considered the reincarnation of the master of masters Chökyi Wangpo, both tertöns (discoverers of hidden spiritual treasures) and yogis known throughout Eastern Tibet and beyond. They remained closed for years in solitary retreat in hermitages and caves on peaks that the master indicated to me by stopping the car to offer khatag in the direction of the places where he received precious teachings from them, and where he practiced in turn in hidden places in the mountains. We had already been in Derghe for a few hours when, at the intersection of three valleys topped by rugged peaks, he offered some yellow flowers that grew in that season and looked like tulips. He turned to a mountain with a rounded tip, where – he told me – another uncle, the yogi Togden Ugyen Tendzin, practiced in summer and winter and attained the state of the body of light, apparently outwitting the communist guards who patrolled his retreat house.

In the biography of the Togden, masterfully translated by Adriano Clemente, I found a significant detail to help understand the determination of these masters in pursuing the path of Ati. I knew the legend of Milarepa who threw away his only possession, a bowl to eat wild nettles, and in “The Body of Light” Rinpoche will tell the story of how a wealthy local family offered the Togden a sheepskin suit lined with fur for his icy hermitages and he bartered it for a certain sacred inscription in stone for the protection of beings.

Those inaccessible places at times shielded only by wooden planks were for the young Norbu and his uncle also places to practice Yantra Yoga, which the Togden had learned from Adzom Drugpa as one of his closest disciples. Anyone who knows the history of lineages knows that Drugpa was the previous incarnation of Namkhai Norbu. The dying lama entrusted Rinpoche’s uncle, the Togden, with the red and white striped shawl, the bell and the vajra intended for his successor. Trying to imagine this teacher-disciple relationship alternating through numerous generations of sages, I observed their places of retreat in the distance from the road. However, even ignoring most of the events made public by the master in his detailed biographies, I could not start to understand the historical role that these lineages of tulkus of monasteries, even important ones, played at that time, openly breaking the rules imposed by their own administrations. Aware of the degeneration caused by money, many yogis refused to bestow on command a certain number of teachings and blessings a day to monks and devotees.

However, I fully understood the privilege of studying with a practitioner of the path of self-liberation, a direct disciple of these solitary tulkus, who often only transmitted instructions to a student from mouth to ear. I must admit that Rinpoche never once uttered special mantras for my hearing alone, except for the invocation of Manjushri, “Om arapatza nadi hum phet”, after I asked him how I could increase my low intelligence. (“You can try,” he said smiling). But being close to him, observing him with his ordinary gestures, and the extraordinary effects of the energy that he transmitted around him, was a constant and unwritten teaching. During his long conversations in Tibetan and Chinese with ordinary people, high lamas, political officials and intellectuals, his voice was to my ears like a mantra that sometimes turned into a lullaby and I would doze off in public, much to Rinpoche’s embarrassment. Speaking of presence in contemplation….

We had two stops in Galenteen and I did not know about the biography of Khyentse already written two years earlier by the master, then updated by him and translated in 1999 by Enrico Dell’Angelo with the title “The Lamp That Enlightens Narrow Minds”. I will therefore discover only later the meaning of many things that Rinpoche told me in those days but which I did not understand or immediately write in my notebook. But they came back to life thanks to expert Tibetologists such as Enrico and Adriano Clemente who transcribed with precision the stories recounted from the same source about those unusual yogis and the places where they were born.

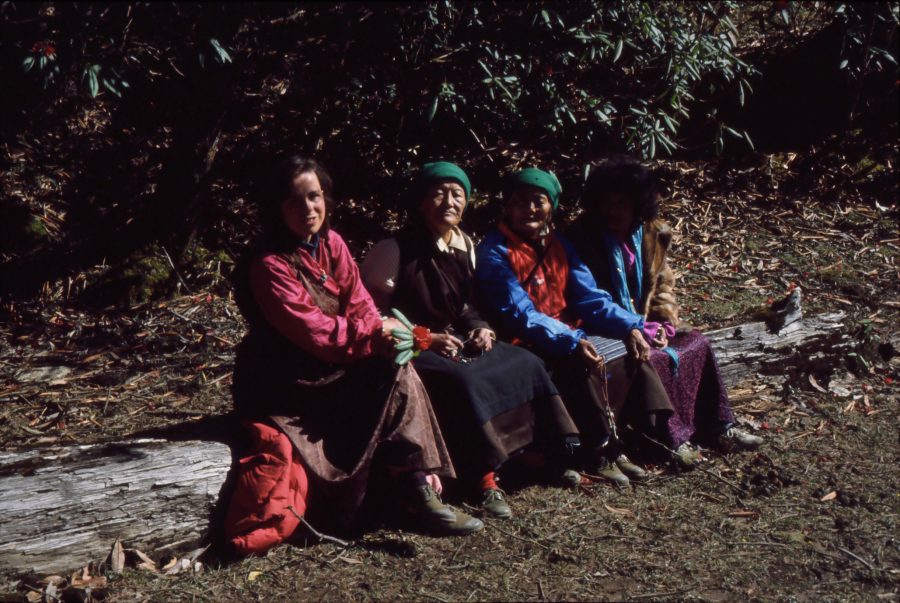

However, I perceived with all my senses the colorful and intense devotion of the nomadic horsemen who came down the main road from Galenteen to welcome us, offering the first visual impact with the people of the isolated valleys. They were primeval-looking men dressed in skins, faces the color of certain red sands of the highlands, and hair that had never seen a brush and often not even water. They rode alongside us as proud and happy as children, shouting propitiatory mantras, waving and throwing khatag in the air, and moving back and forth on the backs of their animals as in American Indian films, surrounded by snow-capped peaks and the air rarefied as crystal.

The nomads of the district of Changra, where Rinpoche’s uncle abbot had built the monastery around which the religious life of his disciples still takes place today, had reached the road that connects the valley to the capital of Derghe to give a worthy reception to the famous nephew of their master.

The sang ceremony in Galenteen after Rinpoche’s arrival

During the steep climb in the jeep, our Tibetan driver amazed in turn by the welcome, their animals raced past us at speed with a procession that seemed to have no end of men with long hair braided with red cords from the Kham ethnic group and groups from other Tibetan clans. We stopped in a very green clearing where a large group of monks had lit the herbs for the sang [smoke incense offering ed.] and we were offered a plate of sweets and candies along with butter tea which we shared with throngs of children accompanied by women dressed in traditional clothes with small and large turquoise or other stones in their hair. Finally we reached our first destination, the temple in the heart of the village about which Rinpoche had already had two dreams during the journey. He had seen the original inscriptions, which he will find in reality, that dated back much earlier than those of the three scholastic traditions, Sakya, Kagyü, and Nyingma, that had alternated in that place of practice for at least eleven centuries.

Galenteen or Galingteng was founded by the legendary Lhalung Palgyi Dorje, direct disciple of Padmasambhava, considered a hero because he killed King Langdarma, who had become a bitter enemy of Vajrayana Buddhism, with a brilliant strategy. For many years Galing and the Lhalung valley were his safe haven from the king’s soldiers who sought him everywhere, and here it is said he obtained the body of light in solitude.

Rinpoche told me the details as we crossed the valley which takes its name from that famous disciple of the great eighth century exorcist responsible for spreading Tantric Buddhism in Tibet and which will become the basis of some of ASIA’s projects. “Dorje” – he explained – “had smeared his white horse with coal and wore a two-faced black cloak to reach the king’s camp in western Tibet. As soon the arrow struck the heart of the sovereign, he crossed a river where he washed the horse and reversed his jacket, escaping the searches of the soldiers who were looking for a black rider, then headed straight into this valley.”

We will soon visit Lhalung, several hours distant on horseback from his uncle Khyentse’s residence. Rinpoche’s family and I were guests at the two-storey house with wooden windows and floors built half a century earlier for the abbot who would move from there to stay in retreat in locations such as Giawo and others that were even closer to places where Palgyi Dorje had lived. In the following days the master visited one of these caves or hermitages together with Cheh during his stay in Galen. The Khyentse residential house was simple accommodation and like the rest of the village it had no electricity, so we depended on sadly bad quality Chinese-made candles that burned sideways and soon left us in the dark.

The word Galen means “to take off the saddle”, but it also refers to the syllable of the family name of another famous sage named Ga Anyen Tampa, direct disciple of Sakya Pandita and spiritual teacher of a Mongol emperor, who stopped there at the beginning of the 14th century. It was here that Ga “took off the saddle” to remain for a long time before returning to court. But it is to Padmasambhava’s disciple that we owe the birth of the gar, or spiritual place, known by his name, entrusted for many years before the revolution to the guide of Khyentse who had predicted the events to come due to the climate of division that was being created among the very administrators of his labrang [monastic household ed.] and within many families.

In the wood-panelled room with the terracotta stove in Chokyi Wangchuk’s house, in addition to Cheh there was also his fellow countryman Keng Leck from Singapore (there are videos of him on youtoube /). Rinpoche often sat on the bed talking to us while continuing to prepare medicines and chudlen pills, or working on the khatag scarves and protective cords that he would distribute to the hundreds of people expected every day at the house, always crowded to hear him speak or receive blessings. The khatag seemed to come to life under his fingers after intertwining and authenticating them with a mantra before distributing them to the waiting line. Many people also asked for one for their children (in nomadic areas they had an average of 3 to 5), for yaks or horses, or even to “protect” the new machines that had been invented to curdle butter more easily.

Except for a week of flu that weakened the master by forcing him to stay in bed most of the time, the days in Galenteen followed one another peacefully with visits from ordinary people and authorities, teachings from the teacher to nomads, and walks along the river. I often went close to the temple, a place of peace and silence, where the inhabitants had gathered together the stones carved with the faces of the deities and the syllables of the mantras that had been stolen during the cultural revolution. The village came to life on the eve of a great Avalokitesvara Long Life initiation ceremony and the grasslands around the Khyentse house were filled with tents. There was a crowd such as I had never seen before with street vendors, hermit yogis, monks and nuns who had come out of their retreats, and even a couple of trucks, one with a crank ignition and the other loaded with beers that had been literally looted.

The crowd of nomads at the Avalokitesvara initiation in Galenteen

Together with the protections Rinpoche prepared and authenticated hundreds of chülen medicines to distribute during the initiation. The next morning in the area around the tent-gönpa that would host the celebrants of the rite, hundreds of other people arrived and I was able to calculate more than 1,500 considering that by the evening the chülen pills had run out. They even came from distant villages that were three days on horseback, drawn by the news spread in a short time from valley to valley of the ceremony in the sacred place of the revered Khyentse to be celebrated by his favorite nephew. Soon the snow lion dances, traditional religious chants and singing began and – most popular of all – folk songs based on the life of the Tibetan “King Arthur”, Prince Gesar, who was considered an emanation of Padmasambhava. I recorded some of them but I fear they have been lost. Rinpoche knew several by heart like all Tibetan children, but growing up he reread as a scholar most of the 50 volumes of the stories about him. His knowledge of traditional songs and dances will lead, I believe, to his contagious passion for the Khaita songs.

The altar of the Avalokitesvara ceremony in the Galenteen gönpa tent

Thinking of the large amount of literary and historical material that he had collected over the years, that evening Rinpoche told me about a technology that will become more sophisticated, practical and widespread twenty years later. He would have liked to catalog and reproduce on microfilm – he said – the many ancient books he had received as gifts and those of the Shang Shung library at Merigar. He sensed that it would soon be an easier operation, as will happen, not with films, but thanks to the scanners of the digital age that was just starting. In the morning, during a dance with Yamantaka masks to propitiate the Tsen, a class of beings who were the celestial lords of Galen, several jeeps arrived with the political authorities from the capital of Derghe, and it was not appropriate to continue with that part of the religious ceremony.

Their arrival was very important for the village and they were invited to a big breakfast under one of the most beautiful tents in the camp. The bosses said that they had already discussed his proposals for schools, hospitals, and social services for nomads in the district council, which included Colondon (or Korondo, in the sacred valley of Lhalungar where we will be going soon), and found them “fantastic”, as Rinpoche translated to me, satisfied, confirming the expectations of the convivial atmosphere of that meeting in which the monks and the head of the monastery participated.

Two monks dressed as Bon priests during the Dances at Galenteen

After a new series of dances based on the myth of the rivalry between a good king and a bad one conducted by monks with impressive paper-mache masks, the actual ceremony began and Rinpoche changed his clothes to wear the ritual robes of his uncle, the Abbot. After the first part of the consecration rituals in the tent-gönpa, surrounded by a growing number of people, the local lama who assisted the master went around the crowd touching everyone on the head with the image of Avalokiteshvara while the monks distributed the chülen pills to the adults.

There was the same crowding the following day even if this time the ritual was preceded by a horse race, a really popular passion. Rinpoche had been put on one of the champion horses who would later win the first race and the excitement of the people around who wanted to touch him made the horse go wild, fortunately without consequences. The race course passed under our window and there was also a race on foot and one for bicycles, old heavy Chinese models. Eventually the finals were held with the winning horses. In the end Rinpoche counted seven victories for the local horsemen (famous throughout the region, he said) and two for the visitors. “There is an ancient tradition here and the jockeys are very strong,” he said proudly.

In the following days the master decided to transmit the “lung” of the tun book, the spiritual practices of the community, to the monks and lay people who had requested it, and during the entire recitation an old lama who was a contemporary of Khyentse held my hands tightly, smiling with his cataract filled eyes. In the previous weeks, taking advantage of Cheh’s stay, Rinpoche had him teach those present the melody of the Song of the Vajra, and the eight movements of yantra yoga to the monks, albeit awkward in their long religious robes. When the ceremonies and the festivities for the initiation of Avalokiteshvara finished Rinpoche transmitted the practice of Phowa to about fifty elders. At the end a very old woman in tears will tell him that before dying she would have liked to see in Galenteen his son Yeshi, incarnation of Khyense Wanghuk of whom she had been a disciple since childhood.

To be continued.

Part 1 can be read here.

Part 2 can be read here.

Featured photo: a group of pilgrims who came to Galenteen for the ceremonies.

You can also read this article in:

Italian