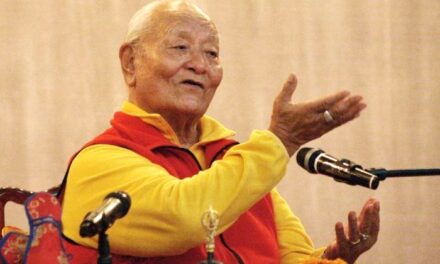

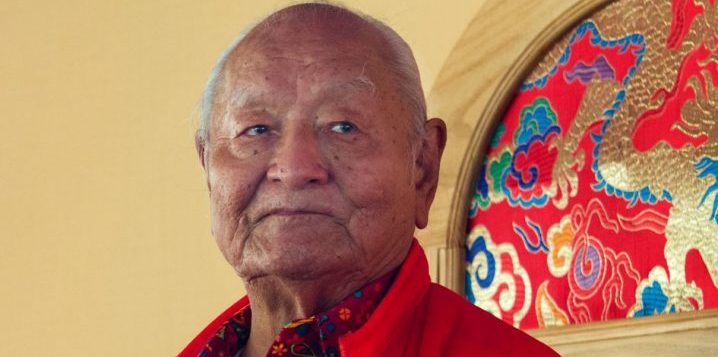

An excerpt from Starting the Evolution, An Introduction to the Ancient Teaching of Dzogchen by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, compiled and edited by Alfredo Colitto, Shang Shung Publications, 2018.

When I arrived in Italy for the first time, many years ago, no one knew what Dzogchen was. The only exceptions were a few professors who wrote articles saying things like, “Various currents of Buddhism exist in Tibet; there is also one called ‘Dzogchen’.” Nowadays, Dzogchen is becoming more and more popular in the Western world. Still, people who hear or read this name for the first time think, “Oh, this must be one of the Eastern philosophies.”

You can consider it a philosophy, a religion, or a spiritual path, if you wish, but it is not like that. It is important to understand that Dzogchen is not really a kind of school or tradition. Dzogchen is our real nature, a potentiality that we all have. It is a very ancient knowledge, transmitted and taught. The way that teaches the methods to discover that potentiality and use it in our lives, is called Dzogchen teaching. We can follow it and learn how to discover our real nature: Total (chen) Perfection (dzog).

It is a very high teaching, but high does not necessarily mean complicated. Dzogchen can be very simple. Why? Because it is based on experience, not so much on study and learning. The teacher explains a little, introduces us to directly discover our real condition, and when we do discover it, then we have that knowledge.

This is something very useful also in a practical way: if we know our real condition, we can overcome all our conflicts or problems. And we also get to know ourselves a little better. So this is what the teaching can give. This is what I have been teaching for more than 40 years.

Dzogchen and Eastern Culture

Every teaching is transmitted through the culture and knowledge of human beings. But it is important not to confuse any culture or tradition with the teachings themselves, because the essence of the teachings is knowledge of the nature of the individual.

If someone does not know how to understand the true meaning of a teaching through their own culture, they can create confusion. Sometimes, Western people go to India or Nepal to receive initiations and teachings by Tibetan masters living there, maybe in some monasteries. Once there, they are fascinated by the special exotic atmosphere, by the spiritual “vibration.” Maybe they stay a few months, and when they go back home they feel different from the people around them. Maybe they dress differently, they eat Tibetan food, they behave in some peculiar manner, and they think that this is an important part of their spiritual path.

But the truth is that to practice a teaching that comes from Tibet, there is no need to try to become like a Tibetan. On the contrary, it is crucial for practitioners to integrate that teaching into their own culture to keep it alive within themselves.

Often, when Western people approach an Eastern teaching, they believe that their own culture is of no value. This attitude is very mistaken, because every culture has its value, related to the environment and circumstances in which it arose. No culture can be said to be better than another. For this reason it is useless to transport rules and customs into a cultural environment different from the one in which they arose.

Dzogchen and Religion

Human beings have created different cultures, philosophies, and religions in different times and places. Someone who is interested in the Dzogchen teaching must be aware of this and know how to work with different cultures, without becoming conditioned by their external forms.

For example, some people might think that to practice Dzogchen you have to convert to either Buddhism or Bön, because Dzogchen has been spread through these two religious traditions. This shows how limited our way of thinking is. If we decide to follow a spiritual teaching, we are convinced that it is necessary for us to change something, such as our way of dressing, eating, behaving, and so on. But to practice the Dzogchen teaching there is no need to adhere to any religious doctrine or to enter a monastic order, or to blindly accept the teachings and become a “Dzogchenist.” All of these things can, in fact, create serious obstacles to true knowledge. Monks or nuns, without giving up their vows, can practice Dzogchen, as can a Catholic priest, an office worker, a laborer, and so on, without having to abandon their role in society, because Dzogchen does not change people from the outside. Rather it awakens them internally.

Dzogchen is not a school or sect or a religious system. It is simply a state of knowledge that masters have transmitted beyond any limits of a school or monastic tradition. The lineage of the Dzogchen teaching has included masters belonging to all social classes: farmers, nomads, nobles, monks, and great religious figures, from every spiritual tradition or sect. A person who is really interested in these teachings should understand their fundamental principle without letting themselves become conditioned by the limits of a tradition.

How to Start on the Path

Students who are interested in discovering their real nature follow a teacher who has that knowledge. In Dzogchen it is indispensable to receive, from a qualified master, what we call direct introduction or direct transmission. We will talk later about what this is.

Dzogchen is related to our physical level, to our energy, and to our mind, because we all have these three existences. So, when we are introduced to that knowledge by somebody who has realized that potentiality, we discover it not as a kind of intellectual understanding but a direct experience. If we discover our real condition and how to remain in it, we can be free from all our problems. But in general we do not know that; we do not even know that there is something to discover.

Discovering and Believing

Discovering and believing are two different things. For example, you might say, “That person is an expert, I like the way he or she explains, I believe that.” Maybe you believe it this year. But next year, you might meet someone even more expert and decide to follow what they say, even if it is different from what you believed the year before. This means that your belief is not really steady. It can change at any moment. But if you discover something through your own experience, then there is nothing to change.

It is not so difficult to understand. How do we know, for example, that sugar and candies are sweet? We do not need any book explaining to us the theory of sweetness. Why? Because we have already discovered it through our experience. Even though we know something intellectually, we are curious and we want to have a concrete experience. If you say to a little child, “Don’t go near the fire, otherwise you can get burned,” the child does not know what you are talking about. It wants to experience it. So maybe one day, when you are not looking, it goes near the fire, touches something hot and discovers that heat can be painful. Then it never loses that knowledge.

In the Dzogchen teaching we apply the same principle. It is not that the teacher explains something and asks you to believe in his words. Of course, if you believe, it is okay.

Faith and belief can be powerful, we know that. Systems like religions are based on faith. However, the principle of the Dzogchen teaching is not so much believing what the teacher said, but discovering our real nature by ourselves. A teacher can help us to understand, explaining for example that in this relative reality we have three levels of existence, that we also call three gates: body, energy, and mind. We can learn that, but we also need to discover it through our personal experience.

Direct vs. Intellectual Understanding

When we want to understand something, we ask ourselves, “Why is it like this?” Then we find some justification: “It could be like this for this or that reason.” We think of it some more, then we decide, “Yes, this must be it.”

This is called intellectual understanding. But in the case of our real condition it does not work, because there is no direct experience. When we have no direct experience we can say, “Yes, our real condition is like that,” but tomorrow or next week we can change our idea. If there is something to change, it means that we have only an intellectual understanding.

For example, I show you my sunglasses, and you see that the lenses are black. You have no questions about that, because you have a direct perception of them through your sight. This is an experience. Now, suppose that I ask you, “Please change your mind, these sunglasses are not black, they are yellow.” How could you do that? How could you change what you see? It is impossible. This direct knowledge that you received through experience it is not changeable. But if I do not show anything to you and I just say, “Once I had some black sunglasses,” then you think, “Oh, he once had black sunglasses.” But a little later I say, “Sorry, that is not true, the sunglasses I had were yellow, not black.” Then you immediately change your idea. “Okay, he said black but he was wrong, now I know his sunglasses were yellow.” Why can you change your mind so easily? Because you had no direct perception of the sunglasses.

So you see, this is the difference when we discover something with our experience or only with our mind. Logic is something very, very relative.