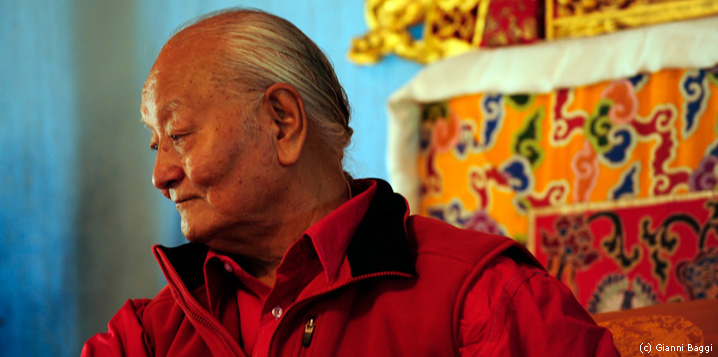

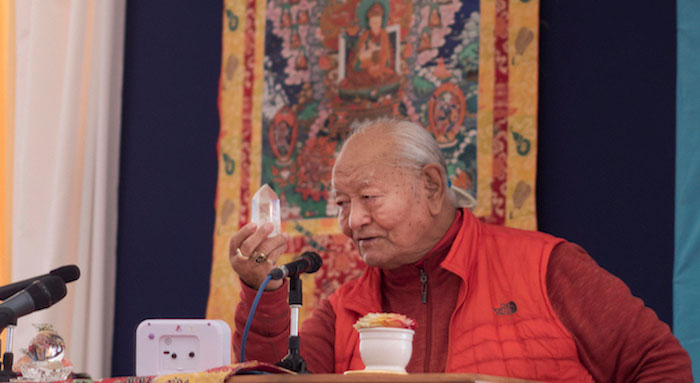

A Teaching given by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu

Webcast from Merigar, August 13, 2002

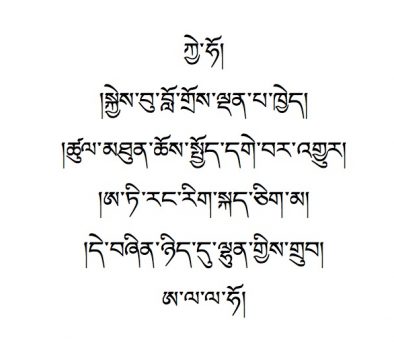

KYE HO!

Intelligent being, listen!

If you practice the Dharma according to the real situation, all becomes virtuous.

The instant presence of your primordial state

Is self-perfected in its very nature.This is marvelous!

Good morning, good afternoon, good evening to all people who are interested around the world! We are very happy to have this communication and to be together spiritually and mentally. We are here at Merigar at our August retreat. We have a very nice day, not so warm but very nice. We also know that there are many people in the cold weather these days, in the snow, but we also know that many of you are having warm weather so let us enjoy this moment together in any case. I want to communicate some very simple teaching to you.

Among many of my Dzogchen teachers, one of the most important was my uncle who was called Ugyen Tendzin (U rgyan bstan’dzin). He was not an intellectual person but he was an excellent Dzogchen practitioner and I received many Dzogchen Upadesa teachings as well as many teachings and knowledge of Yantra Yoga from him. He was one of the foremost students of Adzom Drugpa.

Adzom Drugpa was a very important Dzogchen teacher who spent most of his life doing practice and had a really very high realisation of Dzogchen. My uncle was an excellent practitioner and teacher, but not like those teachers who have studied for a long time in an intellectual way. When I last saw him in 1954 or 53, I don’t remember which, I had gone to see him to receive some particular knowledge of Yantra Yoga. I spent a few days with him and when I left I asked him to give me some advice. In general we have that attitude when we are following a teacher, we ask him to give us some advice. It doesn’t mean that I am telling you to do that, (laughter) But we have that attitude.

For example I asked my teacher at College and he gave me some advice. I also asked other teachers like Ayu Khandro and they gave me some advice. This advice is mainly about how to integrate teaching and go ahead with our practice. Some teachers write pages of advice. For example, when I asked advice from one of my teachers, Kangkar Rinpoche, he wrote me a little booklet of more than fifteen pages.

If someone is a practitioner and also has intellectual knowledge it is easy to write it down. But when I asked my Uncle Togden, he said, ” OK then, get a pen and some paper. You write and I will tell you.” He only gave me four verses.

This was his advice. Of course I considered this to be something very important and I want to explain these four verses to you so you too can maybe understand how advice on the essence of knowledge is given.

This was his advice. Of course I considered this to be something very important and I want to explain these four verses to you so you too can maybe understand how advice on the essence of knowledge is given.

This is the first verse. Kyebu (skyes bu)means person. When we say ‘kyebu’ in Tibetan, it could be male or female. In English we say ‘person’, which could be male or female. Lodrö denpa (blo gros ldan pa) means not only a person but one who has a capacity of understanding, for example, what is a good way, what is a bad way; a person who can understand and also apply that understanding. In general we say that this is the characteristic of human beings. Human beings are different from animals. Animals do not have that capacity. People can explain, can talk, can communicate, not only communicate but they can judge and think.

Some people are able to communicate and distinguish the difference between good and bad. That kind of person is called lodrö denpa and has this kind of intelligence. So this was addressed to me, “You are the kind of person who has that capacity”. It means, “You aren’t stupid”; if I explain something, you know how to understand and apply it. This is the first verse.

The second verse has a very condensed meaning. Tsulthun chöchöd gewar gyur (tshul mthun chos spyod dge bar ‘gyur). Tsulthun means we know how to apply everything according to its condition. It is a very important word. In general we human beings know a lot of things. But even if we know a lot sometimes we tend to go more with our fantasy and interests. This, however, doesn’t correspond to the real condition. The real condition means how it is, its real function.

We are in samsara and we know what the condition of samsara is like. It is not always pleasant and is made up of a lot of suffering and problems. When they have problems, some people get upset immediately because they do not notice or understand what the condition of samsara is like. If we are aware that we are in samsara and know what the situation of samsara is like, when we have a problem there is no reason for us to be too upset. Of course when we have some problems, it isn’t very nice and we are not happy, but we know what the situation is like so we can accept it the way it is and do our best to overcome and diminish problems. This way we don’t get charged up and accumulate tensions and even when there are problems, they become lighter instead of heavier. This is called knowing how the situation or the condition is.

Then, in general, when we are following any kind of teaching, first of all our teachers introduce us to or teach us the Four Mindfulnesses. Why do they teach the Four Mindfulnesses first? Because it is not something that we have invented or created but is the real condition of our lives. But even if it is our real condition, we are not aware that it is. For this reason, teachers make us understand and be aware that the situation is like that.

The First Mindfulness talks about being aware of the preciousness of the human condition. When we study in a more intellectual way we say that there are eighteen conditions. We are free from eight of these conditions. For example we are not in the hell condition, we are not in the condition of animals, we are not prêtas, we are not people without the capacity to judge or to speak. We are not in a country or place where there is no teaching, no transmission, where we don’t know what the teaching or the path is. Even if we have a human birth, if we are in only one of these conditions then it is not so easy to be on the path. So there are eight different categories. But these eight do not really totally represent our condition. This is only a kind of example. We are free from all negative conditions; this is the real sense.

And then there is jorwa chu (sbyor ba bcu), which means the ten things that are perfected. Of these, five perfections are related to the individual and five are related to our circumstances. Those who are interested in intellectual study learn these topics one by one and when they have learned them they think that they have realised that knowledge. If we want to explain these type of details to someone, then we will be able to explain better, but in the real sense, the principle is not doing analysis; the principle is knowing, understanding concretely what the real sense is. For instance, if we compare ourselves to an animal such as a dog, a nice dog, a very famous dog, even though that dog may be very famous, very good-looking, it cannot judge and think and follow teaching and do practice as we do. So it is very simple to compare ourselves to any type of being in order to understand that we have a very special opportunity.

When we speak about realisation such as that of my Uncle Togden we are not talking about ancient history; it happened very recently during the Cultural Revolution. So if this type of realisation still exists that means that there is this possibility and that this possibility is related to transmission, to a method of practice. We have method, we have transmission, we have a teacher. Also the transmission has not been interrupted. We have all these things which means that we have a very good opportunity to follow teaching and do practice.

So we can really reflect on how precious our human existence is because we can truly have some realisation. Having realisation means that we are totally free from samsara, free from all suffering. Not only do we become free ourselves but we can help many other sentient beings. Some people say, “Oh, I want to help others”. It is a very good intention but before we can help others we need to have some realisation ourselves. If we have no realisation or knowledge, we cannot help other beings.

Helping others doesn’t mean that we go and give a little food or water or some other type of help. That kind is necessary but it is not real help for sentient beings because they are transmigrating continually, infinitely in samsara. Helping means that we liberate someone from that type of samsara, we do something directly or indirectly. So to do these things we need to have certain realisation and knowledge. If we want to help someone who is ill, we really need to be a good doctor. That means we need to study to become a good doctor. It isn’t enough that we go to that person, offer a little water and say that we are helping them. That is an example.

Our realisation is very important. All these possibilities are in our hands. Many teachers give advice saying that realisation is in our hands. That means that the teacher gives us transmission, methods, and we know what we should do now. Now realisation is more or less in our hands but whether or not that realisation becomes complete depends on us. Remember what Buddha said, “I give you the Path, but realisation depends on you.” We have that kind of condition so this is the First Mindfulness.

The Second Mindfulness is something that we should always remember: the knowledge of impermanence. Even though we have this precious path and transmission in our hands, we exist in time. Today we think, “Oh, I’ve received a wonderful teaching and in a few days I want to do a personal retreat. I want to practice!” But after a few days we go back to our job and meet lots of problems and think, “Oh, I can’t do this today because I’ve got a lot of important things to do, but I’ll do it next week!” When the next week arrives we still think, “Ah, I’ve still got a lot of important things to do. Maybe I’ll do it the following week.” Next week never finishes, it always goes ahead and one day we arrive at the end of our lives and we have a surprise. “Oh, this is the end of life! What do I do now? What did I do?” And we observe and discover that we have spent all our life thinking of practicing next week but what we have concretely is a collection of teachings. We have always written everything down but we don’t really need it because when we die we can’t take anything with us. That means we have not been aware of time and we have lost that good opportunity. So even if there is a good opportunity, if we do not understand and apply it, it has no value.

In the Dzogchen teaching we say that everybody has infinite potentiality. Our real condition and primordial potentiality is just like that of Enlightened Beings. But we are ignorant and are not in that knowledge. If we are not in that knowledge, even though we have that quality it does not function. So it is very important that we apply [our knowledge] and realise something.

Time always passes very quickly. If we observe children when they are growing up, after a year or two has passed when we see them again we think,” How much they have grown!” We only notice the children growing but don’t notice that our time is passing. Even when we look in the mirror it is difficult to notice because we look there every day and the changes are gradual not immediate. We seem more or less the same. Spiritually we always feel young.

When I was very small one of my Chöd masters told me, “I never had time to be a young man.” And I asked him, “How is that possible?” He replied, “Because I still considered myself to be a child. I always felt like that. Then one day someone called me an ‘old monk’ and I discovered that I was already old!” That is very real because we still have the same feeling that we had when we were young. So it is very important that we know that time is passing.

Now it is summertime and if we think about next summer it seems a long way away but actually it arrives very quickly. When I draw up my retreat program I always notice that after a month, four months, five months we will do this and that retreat. I still think we have lots of time until we reach that point [in time] but then going ahead, day after day passes and becomes history.

So it is very important for practitioners to remember that time is passing quickly. It isn’t necessary that we concentrate on our death. If we concentrate on our death too much we become pessimistic and also feel bad. We don’t need to do lots of visualisation of death but we should understand that it is something real. We must be aware and present about everything that is real. Being present about time is very important. First of all it is very important for the teaching and the practice. That way we can realise something.

It is also very important in ordinary life. For example, if you are a young person, you should go to school and study. This is your duty in our society in our human condition. If you do not study and travel around instead, then you lose time. At the end, when you are thirty years old and start to study it is not so easy. When you know that time is passing you can study and do what you have to do so that you will have more time later on to practice and do other things.

It is also very important for relationships in families and between people such as husband and wife who marry and stay together. When their emotions diminish, then all sorts of problems manifest. At that moment they think, “How can we live all our lives this way?” They think like this, get charged up and accumulate and develop tension. If you are aware of time when you get married, then you think, “We want to be together, helping each other and collaborating, we want to spend our lives together”. When time passes and your emotions diminish you won’t have this idea, “Oh, how can we spend our lives together?” because you know what life means. Life can be one day. Life can be one week, or even some years. There is no guarantee. Our life is just like a candle lit in an open place.

There are three very precise facts. One is that we really die one day. Another is that there are plenty of secondary causes for dying. Another thing is that there is no guarantee whether we live a long or short time. When we know these things we can become more aware of the situation. If we become more aware of time then we can relax the arguing and not paying respect to each other. Time is passing and it is impermanent.

We exist not only in time, but in general everything depends on our actions. We cannot exist without doing something; we are always in action. In this case it is very important that we know that we must not create negative karma and that the situation of karma is related to time. We must always be aware of karma, too. If we accumulate negative karma in any case we experience the effect of it. So instead of accumulating negative karma, when we are aware and the potentiality of negative karma arises, we try to purify and eliminate it. That means that we are doing our best. This mindfulness of karma is also very important. Why do we need to be aware of negative karma? Because we are also able to be aware of the situation of samsara. We know that samsara is full of painful problems and that all of the suffering of samsara is produced by karma. Karma is produced in time so in this case it is very important that we are mindful of this. With mindfulness we don’t create negative karma and in that way we have fewer problems of samsara.

So you see these Four Mindfulnesses are not something that we have invented in a theoretical way but are something concrete. First of all we need to know this and then apply this knowledge in a correct way. I’ll give you a very simple example. If we go to a foreign country which is very different from our own, such as a country where there are some very heavy and terrible rules, then we must be aware of the rules and the situation in that country. We cannot do anything against the rules of that country. It does not depend on whether we like or dislike the rules, whether we agree or disagree. If we want to return from that country then we must be aware, pay respect, and not argue with the people. This is called, ‘how the situation is’. We know about the situation, apply ourselves to that so then we will have fewer problems. In the same way, the Four Mindfulnesses are the universal situation of our condition.

Not only the Four Mindfulnesses but there are infinite things. We cannot make a dictionary of them all and even if there was a dictionary, we couldn’t use it. But it is much better that we use our awareness, applying it as we should. That is why in the Dzogchen teaching when we speak of our attitude, we always say that we should work with circumstances. Circumstances mean that whatever the situation is like, we apply [our knowledge] in that way. Some people say, “Oh, I couldn’t come to this retreat. I’m really sorry because my mother is really ill and in the hospital”. Or others say that they have some illness or problem. Or some say that they can’t come because if they do they will lose their job. So then I reply to them, “Don’t worry. When you have the possibility one day, you go and study and follow the teaching.”

Remember that the most important thing is that we work with our circumstances. If circumstances indicate that you shouldn’t come to this retreat, that you should do these other things and you don’t pay respect and come to the retreat, maybe later you will have a lot of problems. So you see, then, what working with circumstances means.

In general it is very important for our practitioners to learn how to work with circumstances. That is why I really like this Italian song that goes, “La vita, la vita è bella, basta avere un ombrella in queste giorni della festa per coprire la testa”. [Life, life is wonderful, all you need is an umbrella to shade your head during these days of happiness.] That means it is sufficient to have an umbrella. But it doesn’t mean that if we have an umbrella we don’t have any problems. For example, today we don’t need an umbrella. A few days ago, however, when there was heavy rain, we needed one. That is called circumstances.

According to the circumstances if we need certain kinds of practices then we can apply them. In the Dzogchen teaching we say that if we don’t feel like doing practice, we should never force ourselves. Some people say, “Oh, if I don’t do practice then my laziness will be stronger than me and I will lose my possibility of doing practice,” and you fight with your laziness. This is a method that is used more in the Sutra style of practice.

If we follow a Dzogchen teacher and ask him, “What shall I do? I don’t feel like practicing today,” the teacher will say, “OK, don’t do any practice. Relax, enjoy yourself”. But don’t relax and enjoy yourself without having presence. You always need your presence. If there is a continuation of your presence then you relax, you don’t practice. After a few days you will discover why you don’t feel like practicing. You can’t feel that you don’t want to do practice without having a cause. There is always a cause, a factor. It’s very important that you give yourself more space, relax and discover what it is. When you discover what it is then you can work with that, you can do practice and have fewer problems.

Practices are not only done in one way. Sometimes we do practice in a formal, ritual way for one, two three, four days or more, then one day we don’t feel like doing it. We feel tired of doing it. That’s normal. But it isn’t necessary that we do that kind of practice. We can do practice in a relaxed way simply relaxing in a state of Guruyoga or doing recitation of the Vajra.

There are many ways of doing practice and that is why we should learn them. We need to learn different kinds of practices so that we can work with circumstances. In Tibetan we say that if someone shows you their index finger, you should reply with your index finger, not with your little finger because it doesn’t correspond. Not even with your thumb because it doesn’t correspond. This is an example to show that we must work with the situation the way it is. It is called working with circumstances and is really very important.

So then you know how the situation is and how to work with that situation. This is the meaning of the word tsulthun (tshul mthun) in the advice from my uncle.

Ugyen Tendzin’s advice continues with chöchöd (chos spyod). Chö means Dharma, applying with our attitude. When we follow Dharma, we try to apply it according to the real condition and according to the way it is explained in the teaching. Today we have many types of these problems in general because a lot of people use the word ‘Dharma’ for political and even economical situations. But this doesn’t correspond. If we apply Dharma it must correspond with the meaning of Dharma.

There was a very important teacher called Atisha who was the source or origin of the Gelugpa tradition but is also considered to be very important in the Sakyapa, Kagyupa, and all the other traditions. Atisha gave some advice not only for a single person but for Buddhist practitioners in general. He said that Dharma must be applied in a correct way, otherwise it can become a source of samsara instead of liberating us from it. Of course, real Dharma never becomes that way, but Dharma teaching is practiced by human beings and those who practice it are called practitioners of Dharma. If someone has some qualifications then he is called “Lama of Dharma”, a “reincarnation of Dharma”, “head lamas of Dharma” then there are many levels, first, second, third and so on. At this point we must be careful because Buddha never taught many levels. Buddha only taught knowledge of Dharma. But we humans have created many of these types of positions.

Once I received a letter inviting me to go to India for a big meeting of reincarnations mainly organized by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. I felt that I was not a big or important lama and that perhaps it wasn’t necessary for me to go. I also had work at the university because at that time we were preparing examinations. So I wrote saying I was sorry but I couldn’t come because I had exams at the university. Later I received a letter from the Office of the Dalai Lama; the Dalai Lama himself asked me to come. So then I decided to go.

One day we were doing an offering, a type of Ganapuja, in front of the big Stupa – I also participated with all these big lamas – and that night I had a very strange dream: we were going to do a Puja in front of this Stupa and they had prepared a very high throne for the Dalai Lama. It seemed to reach halfway up the Stupa. There was also a staircase for the Dalai Lama to get to the top. He arrived and started to go up the staircase. There were many other thrones there, first level, second level, third level and so on. All the big important lamas were running to take up their positions. Then I was a little surprised but I was worried about the Dalai Lama. I thought that when he got to the top his throne might collapse because it was too high and couldn’t balance well. I was really worried and communicated this to the Dalai Lama mentally. He had climbed about five or six stairs when he turned around and I thought, “Oh good. He has understood my communication.” And really, he then came back down the stairs. In front there was another throne that was much lower and quite stable so he went there and sat down. Then all the other lamas didn’t have the courage to sit on the same level as the Dalai Lama and so everyone sat on the ground and I was very satisfied (laughter).

Sometimes we have these kinds of problems because people consider that positions are very important. In the real sense there are no positions in the teaching. What is important in the teaching is knowledge, understanding, and transmitting that, applying teaching that way, not using it for power or position. This is what we call chöchöd (chos spyod), applying Dharma in this way. This is the advice of my uncle.

When I told my uncle that I was going to central Tibet, he immediately said, “Oh, you reincarnations! You are always going around with lots of monks and horses. This doesn’t correspond in the real sense.” I told him that I had no intention of doing things in that way. In the real sense this is true because I traveled with my family in a very simple way. It was also part of the political situation of the moment. And even if we had wanted to do things in the old way, we didn’t have the possibility. It didn’t mean that I was very clever.

So gewar gyur (dge bar ‘gyur) means that you work knowing how all the conditions are. If you follow Dharma you apply it as it should be applied, then everything becomes positive and virtuous and there will be no problems. This is the more relative condition.

Another verse says ati rangrig kechigma (a ti rang rig skad cig ma). When we talk about our real knowledge or understanding that means that we Dzogchen practitioners are following Atiyoga. Ati means primordial state: the primordial state of ourselves. We are not talking about the state of Enlightened Beings. Rangrig (rang rig) means our knowledge of instant presence of ourselves which is not something that we are building or constructing but rather that we discover our real condition. This is always beyond time. When we say beyond time it also means instantaneous, not first, second, third and so on. That is our real knowledge or understanding, and that understanding is not constructed in any way, it is simply knowing how our real condition is. It manifests as the self-perfected state.

In general we say that knowledge of the Dzogchen teaching is beyond effort, beyond construction. That knowledge is also related to our relative condition. That is why I always say that it is very important that we integrate all our experiences into practice. Life should become practice, not thinking that practice is something apart. For instance some people consider the tun book to be Dzogchen practice. How do we do this practice? If we have some time we do the short tun, if we have more time the medium tun, and if we have still more time the long tun, the Ganapuja and so on. Then people have the idea that the practice is that and think that they have to do tun practice and during retreats we do practice together and people are satisfied. When we finish the retreat we go home, some people to the city, others to the countryside, some people live very far away from other practitioners, and they say, “How good it was to do practice together during the retreat, but now I am alone I can’t do any.”

It is very important that we know what practice means. Practice means not only doing collective practice together. Collective practice is one way and when we have the circumstances, such as a lovely day when most people are free, then we can gather some place and do a very nice Ganapuja. But very often we don’t have these possibilities. When we have no possibility we need to practice in an easier condensed way, such as doing Guruyoga with the White A in a thigle. We simply pronounce A and remain in that presence. With that presence we relax in instant presence. Just that is practice. It is not so difficult. And also if we simply try to be aware, aware of the Four Mindfulnesses in daily life and also aware of how the situation is, what we are doing at that moment, this is also practice. If we are doing practice of being aware, we notice if we are charged up and have a lot of tensions. Then we can relax and have more benefits and make our lives more comfortable. This is an example of how we go ahead with our practice during our lifetime.

Now we are living the 2000’s, in modern times and communication is very easy. Even if we don’t live near other practitioners it is not difficult to communicate with them. The same is true between groups of practitioners. It is very important that we communicate among ourselves and pay respect to each other. There are a great number of human beings on this earth but how many of them follow teaching such as the Dharma teaching of the Buddha? And in particular, how many of them are Dzogchen practitioners? If we compare them to the quantity of humans in the human condition on the earth, there are almost none. We only have a few practitioners on the earth and so it is essential that we communicate, pay respect to each other and collaborate among ourselves. We know that human problems are very much related to our egos. In particular, in these modern conditions, we are very busy and we don’t have much time to dedicate to teaching and practice. That possibility is also very limited by our egos and the dualistic condition.

For instance, someone meets a teacher, follows that teaching, and creates a small group. Instead of learning the real sense of the teaching that person always remains blocked with this group saying, “We are students of this and that lama, this group, that group.” I am not saying that you shouldn’t follow different teachers and different groups, but you must understand the limitation of schools, the limitations of groups, because all these limitations are the source of samsara. The teaching doesn’t teach you how to limit. If someone teaches you that, it is not teaching, it is some special teaching of that person. You should know this and not follow that person. Teaching is for liberating us from limitations. If it corresponds to liberating us from problems then even if it has different names, it doesn’t matter. It may even be called a Dzogchen group but if it teaches some kind of limitations it is better that you don’t follow it otherwise it means you are not following the Dharma teaching as it should be.

It is very dangerous to spend a long time moving in the wrong direction because we lose all our precious opportunities. Life becomes practice.

The principle of the Dzogchen teaching is tawa, gompa,and chödpa (lta ba, sgompa, spyod pa). Tawa means point of view, learning what our real condition is and how we can get in that state; all these types of considerations are point of view. Gonpa means that we are not only explaining or learning in an intellectual way, doing analysis, but we really apply [our knowledge] in order to discover how and what our real nature is. In the teaching, even in the Sutra teaching, in the Tantra teaching, in Dzogchen, our real nature is explained as being beyond explanation. But we can have knowledge of it with our practice and our experience. That is the reason we say that we must “taste”, not just talk and make analyses.

I always give the example of sweet. If someone has never had the experience of ‘sweet’ in their life, that person cannot understand what sweet means. But if someone tastes a small piece of a sweet then they have already discovered what sweet means. There is nothing to change that idea. When we have no knowledge, then there is something to change. Sometimes we have the idea that we believe this or that, but it means that we have decided with our judgement. We believe that things are that way even though we have no real experience. If we have no experience, today we believe in white but tomorrow we may believe in red. That is an example to show that we should practice meditation. And the knowledge that arises from meditation we need to integrate with our chödpa (spyod pa) or conduct.

Chödpa doesn’t mean a series of rules about what we can or cannot do. If it is necessary we can always learn such things and use them. But no kind of rules can really correspond globally to how our situation is. They can only correspond if we are really being aware. When we are aware, we do our best and can really manage to overcome problems. For this we must develop our clarity and to develop our clarity we need to practice. With this knowledge finally we discover that we can develop our attitude in order to integrate in that state. Then, for practitioners, life becomes practice.

When we say ‘Dzogchen practitioner’, we don’t mean someone who does a retreat for three years, three months, three days even though Dzogchen teaching doesn’t say not to do that. If you like you can dedicate not only three years but all your life to practice, like my teacher Ayu Khandro who spent most of her life in dark retreat. There are no limitations. The teaching is for all sentient beings, not only for a few people who have the possibility to spend [their lives] in the dark, or in three or seven year retreats. Not everyone can do that. Most people have families; they are fathers and mothers with responsibilities.

Sometimes people who have this kind of responsibility decide to do a three-year retreat and leave their wife, their children, their house, job, and everything. Maybe they have a very nice idea that if they do a three-year retreat they won’t need anything, they will be realised without need of a house or job. But three years passes very quickly and when it is over they are more or less the same. When they come out they have no wife, no job, no family, nothing! Their realisation is that. It means that they are lacking awareness of how the situation is concretely. If they have a guarantee that they will become fully realised in a three-year retreat, then it is not so bad. But I think that nobody can guarantee that they can have realisation in three years. That is why we do not ask people to do that kind of retreat.

People are free but it is very important that we have such knowledge and learn how to integrate our lives with practice. Following Dzogchen teaching means that we are not changing anything. In Dzogchen we say beyond modifying, beyond changing anything. How we were before, we continue in that way only now with knowledge and the capacity to integrate with it. This means that we go ahead as we were before but in instant presence, integrating. This is what we should learn.

When we really become a Dzogchen practitioner we are not conditioned by dualistic vision, we are not always distracted. When we speak with someone or we do something, our actions, our mind, everything is governed by instant presence. Many people ask how we can be in instant presence at the same time as thinking and judging. That is the reason we do Rushen practice at the beginning of Dzogchen. We do many kinds of Semdzin practices for noticing and distinguishing what is at the level of mind and what is beyond mind. When we are beyond time, although time can be within that dimension it does not govern us.

For example, when we are the real potentiality of the mirror, it doesn’t mean that the mirror cannot reflect all kinds of things. Everything related to time manifests in the mirror. First there may be a dog in front of the mirror, then the dog goes away and there is a man. The dog doesn’t always remain in the mirror because now there is a man. That means being in time. If, for instance, we are on a plane when we go to the toilet there is a red light when it is occupied and we have to wait for someone to come out in order to enter. This means time: the time someone enters the toilet, the time they come out and the time we go in.

Beyond time is not that way. Beyond time is just like the mirror in which everything can manifest. When we are in the state of contemplation or instant presence, everything that is related to mind can manifest. When we talk for an hour, we don’t have to be distracted. If we are good practitioners we can be in instant presence and talk, sing, judge.

It is for this reason that in the teaching it says that Enlightened Beings are omniscient. They have the wisdom of quantities and qualities because they are in the Dharmakaya, not in time, and can manifest everything. So we should know what the level of our mind is, what our real nature is, and integrate our attitude with everything. When we have this capacity it means we are really becoming Dzogchen practitioners.

This is the aim, the point of arrival not only for Dzogchen practitioners but other kinds of practitioners – it is easy to understand that – but our way of applying methods and following teaching is different. The characteristics of the teachings of the Path of Renunciation and the Path of Transformation are different and they use different methods to get to that point. But we should not think that different methods mean some type of conflict. Everything is relative particularly for Dzogchen practitioners. Any kind of method whether it is Hinayana or Mahayana style, if we need it and know how to do the practice, we can apply it, even if it doesn’t belong to the Buddhist tradition; it doesn’t matter, we can use it. The principle is our knowledge, which is like a central pillar because then we can integrate everything. We don’t need to be limited and should always try to free ourselves from our limitations. So this is the characteristic of Dzogchen teaching, how it is taught and learnt.

So I have explained a little about Dzogchen teaching because the last two verses of my uncle’s advice are about that. I promised to explain these four verses, so now I have finished the explanation.

Originally published in The Mirror issue 62, 2002

Current version edited by L. Granger

Photo by Gianni Baggi