By Rachael Stevens

Snow Lion 2022

264 pages

ISBN – 9781611809695

Review by Alex Studholme

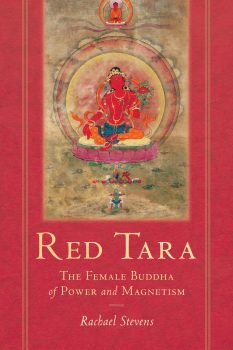

Red Tara is the more esoteric, sexualized counterpart of the more maidenly or motherly forms of the female Buddha, the ubiquitous Green and White Taras. Red is the colour of desire and Red Tara is invoked in order to apprehend an object of desire. Her function is not to save or protect one from fear, but to subjugate and magnetize, her two main iconographic attributes being an iron hook, to summon, and a noose, to bind. She can be called upon for all kinds of things: to control the forces that stand in the way of the building of a monastery, or to amass the resources needed for a long meditation retreat, for example. But her practice is also used by yogins and yoginis to attract a consort, the noose visualized as lassoing the neck and the iron hook as grabbing the heart or genitals of a potential partner.

Red Tara is the more esoteric, sexualized counterpart of the more maidenly or motherly forms of the female Buddha, the ubiquitous Green and White Taras. Red is the colour of desire and Red Tara is invoked in order to apprehend an object of desire. Her function is not to save or protect one from fear, but to subjugate and magnetize, her two main iconographic attributes being an iron hook, to summon, and a noose, to bind. She can be called upon for all kinds of things: to control the forces that stand in the way of the building of a monastery, or to amass the resources needed for a long meditation retreat, for example. But her practice is also used by yogins and yoginis to attract a consort, the noose visualized as lassoing the neck and the iron hook as grabbing the heart or genitals of a potential partner.

This book has its origins in the moment its author Rachael Stevens, entering the precincts of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, bought a small book on Red Tara by Chagdud Khandro, the Texan wife of the esteemed Nyingma master Chagdud Tulku. Her interest was piqued, leading both to a doctorate from Oxford University and to her own personal practice within the Chagdud sangha and other Tibetan Buddhist groups. The result is a work that, while firmly academic in style, also conveys a strong sense of Red Tara as a real, live presence in contemporary Buddhism. After a long general introduction to Tara – rehashing some fairly familiar material – Stevens presents us with a wide-ranging appraisal of Red Tara that fills a significant gap in western understanding of the Tara cult as a whole.

The practice of Red Tara is found within all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism and is rooted mainly in texts brought from India during the 11th century. Stevens concentrates her study on the way these Indian texts have been received by the Sakya school and on a modern terma cycle of a Nyingma lama called Apong Terton (1895 – 1945), which is the basis of Red Tara practice in the Chagdud Gonpa Foundation. Intriguingly, Apong Terton is said to have been reincarnated as the 41st Sakya Trizin, who was, as it were, reacquainted with the Red Tara terma in exile in India by one of Apong’s disciples, who had travelled from Tibet to meet him. On his way, this same disciple also bestowed the initiation of the terma on Chagdud Tulku at Tso Pema.

The tone of both the ancient Indian texts and the modern terma is occasionally overtly magical. One of the Sakya practices, for instance, involves “ink made from the naturally-occurring blood of a twelve-year-old girl”. Chagdud Tulku, meanwhile, developed his own Red Tara practice to include a method of healing with crystals. Both collections include instructions on fire puja. And the Nyingma cycle also includes recipes for chülen pills, as well as a Red Tara long-life practice. We can see, then, how a Red Tara mandala and a special prayer invoking the goddess might be offered to the Dalai Lama by the monks of Mindroling in 2005, when His Holiness was believed to be facing extreme internal and external obstacles.

Stevens includes a chapter on Red Tara as Pitheshvari, a wrathful red goddess depicted in dancing posture, whose various body parts correspond to the twenty-four main pitha sites in India, where yogins and yoginis gathered for ganachakra. Stevens also demonstrates the different ways in which the assembly of Twenty-One Taras is interpreted to include forms of Red Tara, as seen in commentaries by the great Indian missionary Atisha, by the Kashmiri layman Suryagupta (who was said to have been cured of leprosy by Tara) and in the Longchen Nyingthig of Jigme Lingpa.

The pre-eminent subjugating goddess of the Buddhist pantheon is Kurukulla, another wrathful red figure, immediately identifiable by her bow and arrow made out of red lotus flowers. (The same weapons are held by the Vedic love goddess Kamadeva and, of course, by the Roman and Greek love gods Cupid and Eros.) Kurukulla also carries a noose and iron hook, and, as Stevens explains, is closely entwined with Red Tara: either seen as an emanation or form of Red Tara, even as “the heart of Tara”, or alternately as manifesting Red Tara as a more peaceful form of herself. However to complicate matters a little, in the Sakya tradition the two deities are in fact not directly linked at all.

Like Red Tara, the Tibetan practice of Kurukulla is also largely rooted in Indian texts transmitted during the 11th century. She is even more overtly a goddess of love magic, using her arrows of desire to bewitch a sought-after man or a woman. The other potential outcomes of her practice are once again numerous, including the ability to see spirits, coerce government officials and pass exams. More commonly, though, she is invoked to accrue wealth and, by lamas, to attract students. A prayer to Red Tara as Kurukulla in the Apong terma reads: “How without relying on subjugation can one gain the qualities to take on disciples? May I subjugate all those to be tamed, both good and evil, by manifesting in them the four devotions.”

But as Stevens makes clear, the practice of both these deities is ultimately regarded as a means to the final Buddhist goal of enlightenment. She quotes, firstly, the Tibetan lamas Palden Sherab and Tsewang Dongyal: “Red Tara… is special for activating our realization and overpowering our ego-clinging and neurotic states. With her help we are freed from the confinement of our egos so we are able to reach out to all living beings with bodhicitta.” Then the western scholar Miranda Shaw, who writes: “As Kurukulla rose in the pantheon, her sphere of influence expanded from the compulsion of love objects to the conquest of conceptual thought, Buddhist teachings and primordial awareness itself.”

Stevens’ book contains a wealth of detail and reveals the considerable variety and nuance of these practices. In the Sakya school, we learn, a certain Kurukulla initiation depends on first receiving the empowerment of Hevajra. In contrast, the FPMT community of Lama Zopa has published a twelve-page booklet on Kurukulla, apparently allowing anyone to perform her rituals without any initiation whatsoever.

You can also read this article in:

Italian