Raimondo Bultrini continues recounting his travels and experiences with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet in 1988. They are at Nyaglagar in eastern Dege, residence of Rinpoche’s root teacher, Changchub Dorje.

The Mamo Cave

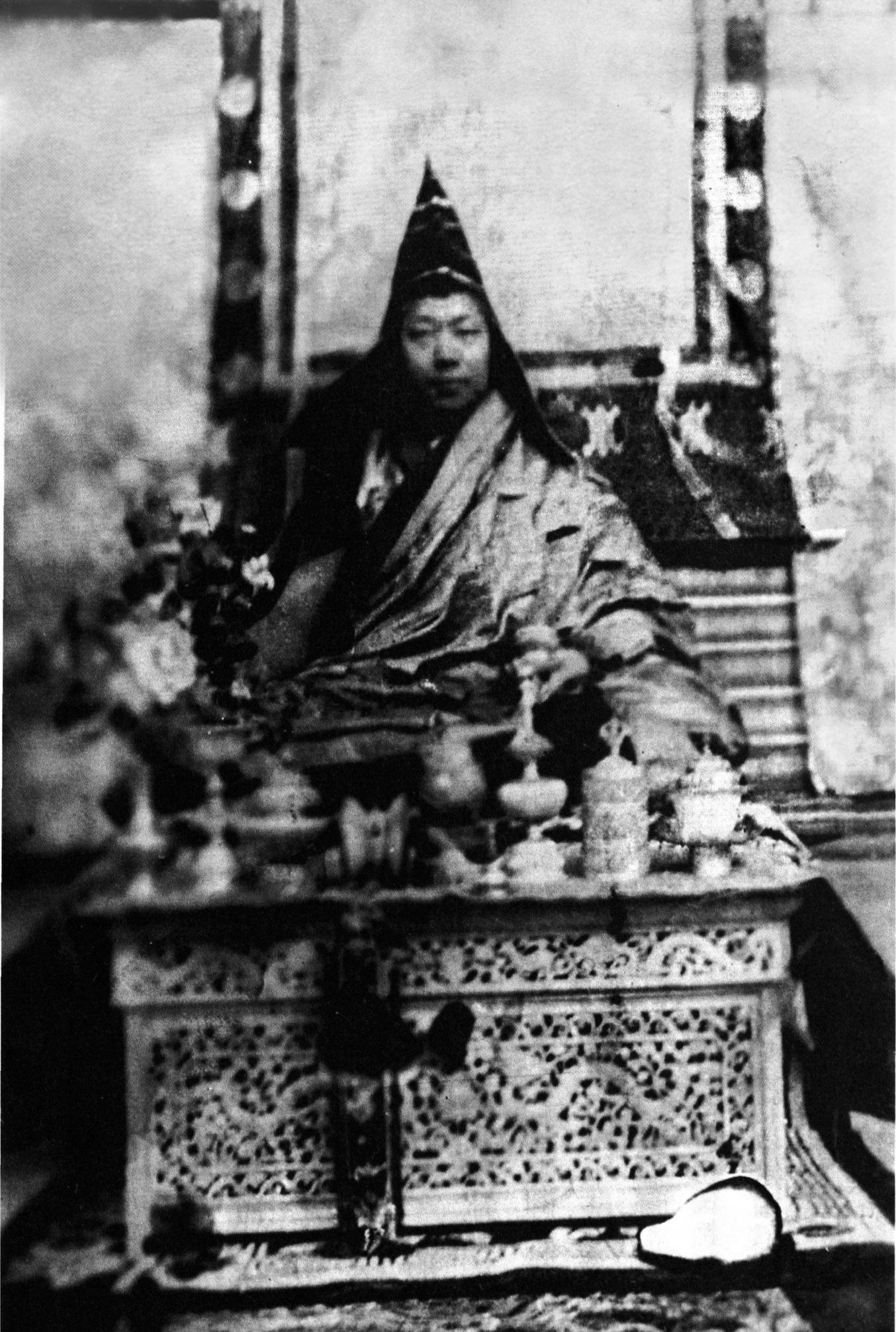

A thangka of Changchub Dorje.

The days in the village of Namkhai Norbu’s master go by quickly. Many people come to visit, but we also often go out for a walk. On a beautiful sunny day, we walk to a nunnery that was destroyed years ago. On the way to the last houses, a large crowd forms and dozens of people follow us in procession.

There are also nuns – some of them are very old – compelled to live all together in tiny houses instead of having the isolation and concentration they need to put into practice the teachings received from Changchub Dorje.

Along the way, the procession of our companions circles around a chorten, shrouded in smoke from the sang, singing and dancing, then crosses a wooden bridge miraculously suspended over the river that goes down to the valley.

Arriving at the top, between rocky canyon-like gorges, Namkhai Norbu points out a place of power to me, a small cave sacred to the Mamo, one of the most powerful classes of Yidam protectors. “You could create some good causes for other beings here,” Rinpoche tells me.

As the procession continues towards the monastery, I enter the hollow where there is only room for one person to sit. I feel quite proud, as if I have received a very important assignment, my first “spiritual” assignment in Tibet. “Creating a good cause”, in Buddhist jargon, means

to do a spiritual practice with the intention of offering other sentient beings the opportunity to encounter the teachings so that they can free themselves from the cycle of rebirth and thus from suffering. But can my practice really help someone else, even beings I don’t know?

I’m not sure why, but I feel that it might. I believe I have been “initiated” onto a path that leads in one direction, to realize my true condition and nature. “Initiate” actually means to begin and since I started on this path, I have had the feeling of being watched and listened to by a thousand eyes and a thousand ears. Particularly here, in these caves in which even the mountains seem to see and hear.

My meditation is an offering to these entities through the sacred sounds of mantras and mudras that have been transmitted for centuries to communicate in a kind of multidimensional universal language, capable of being understood even by pure spirits. But then, as usual, come the thoughts that disturb and unsettle me.

Pride: does being here and being held in regard as a disciple of Rinpoche, surrounded by affection and attention, correspond to a precise design, to predestination? It is this land that gives a higher meaning to every event in life. In my eyes each privilege becomes the expression of an acquired merit.

Ignorance: if this is indeed the case, why do you feel confused and powerless inside this cave? What are you doing here? I recite the mantras automatically, my mind following my thoughts. I am not focused with all my senses on the essence of what I am doing and everything loses value.

I have to get out of the cave and my thoughts come with me, but now there is the distraction of the landscape opening up before my eyes. The river cuts through the valley between two wide mountain gorges sloping towards the horizon, and the village ends with some small crops on terraces. The rocks, as red as a sunset, seem to have been sculpted to feed the popular imagination, which here, just like in Galen, sees in them the likeness of horses.

I walk with the master and grandsons of Changchub Dorje near the large white chortens of the village. Some approach for a blessing, others merely smile, lowering their heads with their hands clasped in front of their faces. Still others show their tongues according to the ancient custom that has survived – apparently – from the era of transition between Buddhism and Bon. In fact, it happened – they say – that during the harsh phases of religious persecution, the followers of Bon were recognised by their blackened mouths due to their continuous recitation of prayers and mantras. Bon means ‘to recite’, and the most observant believers did nothing else from morning till night. Thus, in order to prove one’s non-involvement in the practices of the ancient shamanic religion, a person would show his tongue to officials and dignitaries.

Symbols of the Lama

Even before his death, Changchub Dorje was considered something of a saint. But after he left his body, at the precise moment he died together with his second wife, the master of Nyaglagar was, as we would say in the West, beatified. For that reason the paintings portray him in the symbolic robes of all the deities of the Buddhist pantheon, with the ritual objects, the halos, in the positions of Tantric practices, where each gesture has a precise meaning for initiates into the secrets of the practice.

A group of thangka still needs to be coloured, but many are already complete, with colorful and luminous tones. In general, these paintings do not depict just one figure. They are always of mandalas, images representing a context that is particular and universal at the same time. The painting always represents the individual at the center of the relative condition of existence. The deity, the realized being, the Yidam or protector is encircled by meaningful figures, belonging to the same class, family, or representing different manifestations of beings, peaceful or terrifying, joyful or angry, seated or dancing, still or in movement. The perspective is always frontal, and the minor figures are arranged in a crown around the main one, enhancing its importance.

Changchub Dorje is depicted in every possible way, surrounded by his sons, who are also practitioners themselves and the lama’s main disciples, his masters, his famous contemporaries, and, of course, the deities. In all, I counted at least a hundred thangka dedicated to the master, and no less numerous the carefully preserved ritual objects and important relics.

Along with ‘malas’ of all sizes, medicine containers, stones, clothing, and anything else with which he had contact, even spectacles, the dorje and phurpa, the ritual objects with which he is most frequently depicted in esoteric drawings, are preserved to illustrate his main achievements.

The dorje represents the masculine principle, the symbolic sceptre of the power of a kingdom that will never decline, the indestructible force of primordial energy that – like lightning – traverses space and time. Its upper and lower parts are identical, generally with five rays and points: one side symbolizes the samsaric vision of suffering, the other the nirvanic vision of happiness. It also signifies spirit and matter, absolute and relative truth, but the supreme value referred to the dorje is that of the immutability of the perfect original condition, regardless of circumstances that change over time.

At the centre of the ten rays corresponding on one side to the five passions and on the other side to their corresponding wisdoms is a sphere of five colors called thigle in Tibetan. From here the visions start and here they manifest: it is the primordial energy that moves everything, eternally.

This is surely the most important ritual object in Tibetan Tantric esotericism. It has the same meaning as the ancient Bön symbol of the svastika, present in many other religious cultures and debased by the shameful exploitation of it by the Nazi regime.

The phurpa is a wedge-shaped knife with four sides. It goes to the roots of man’s attachment and reaches the centre of the target moving from all cardinal directions. Thus, with the dorje in his right hand and the phurpa in his left, Changchub Dorje represents the realization of a teaching that came down to him unchanged through the millennia.

Among the objects preserved is also a damaru, the small two-sided ritual drum with strings at the ends of which are the little balls that strike the skin of the drum: the player rotates his wrist to give the rhythm. The sound and size of the damaru vary according to the type of practice. The damaru most commonly used by Changchub Dorje is specific to Chöd, one of the most secret and interesting practices in Tibetan Buddhism, popularized by a master who lived in relatively recent times, Machig Labdrön.

There are many types of Chöd practice, but the principle is the same for all, that is to ‘cut off’, as the Tibetan word itself says, to cut off all attachment at the root, starting with attachment to oneself, to one’s own person.

With this intention, the Chöd practitioner offers up his or her physical body, mind, sensations, energy, everything he or she possesses as food for spirits and divinities. To invite them to this macabre banquet he uses the damaru and a small trumpet made from animal bones. Then he uses visualizations and mantras to communicate his intention to these beings and to ‘authenticate’, or make sacred, his sacrifice. Just as Buddha offered his body as food to tigers to alleviate their hunger, so the chödpa offers himself or herself entirely for the benefit of all beings.

It is a practice that requires a great deal of concentration and develops its full potential in special places, such as Tibetan cemeteries, where corpses are left out in the open for vultures to feed on.

Everything happens naturally in the vision of the chödpa as he or she – quietly seated – invites spirits and deities with the sounds of the ritual instruments. In his imagination, a dance of monstrous ravenous figures begins around his body, and, as if that were not enough, the practice should ideally take place in a cemetery so as to create the strongest possible sensations. In this way one works with the tantric principle that attributes the creation of a particular energy to each movement – whether physical, psychic or emotional. This energy is the fuel for reaching even higher levels of experience.

Conquering the fear of death by evoking it with the loud fracas of drums and bells in the middle of a cemetery is certainly an original system, but one that is difficult to apply in the West.

The Yab Yum Union

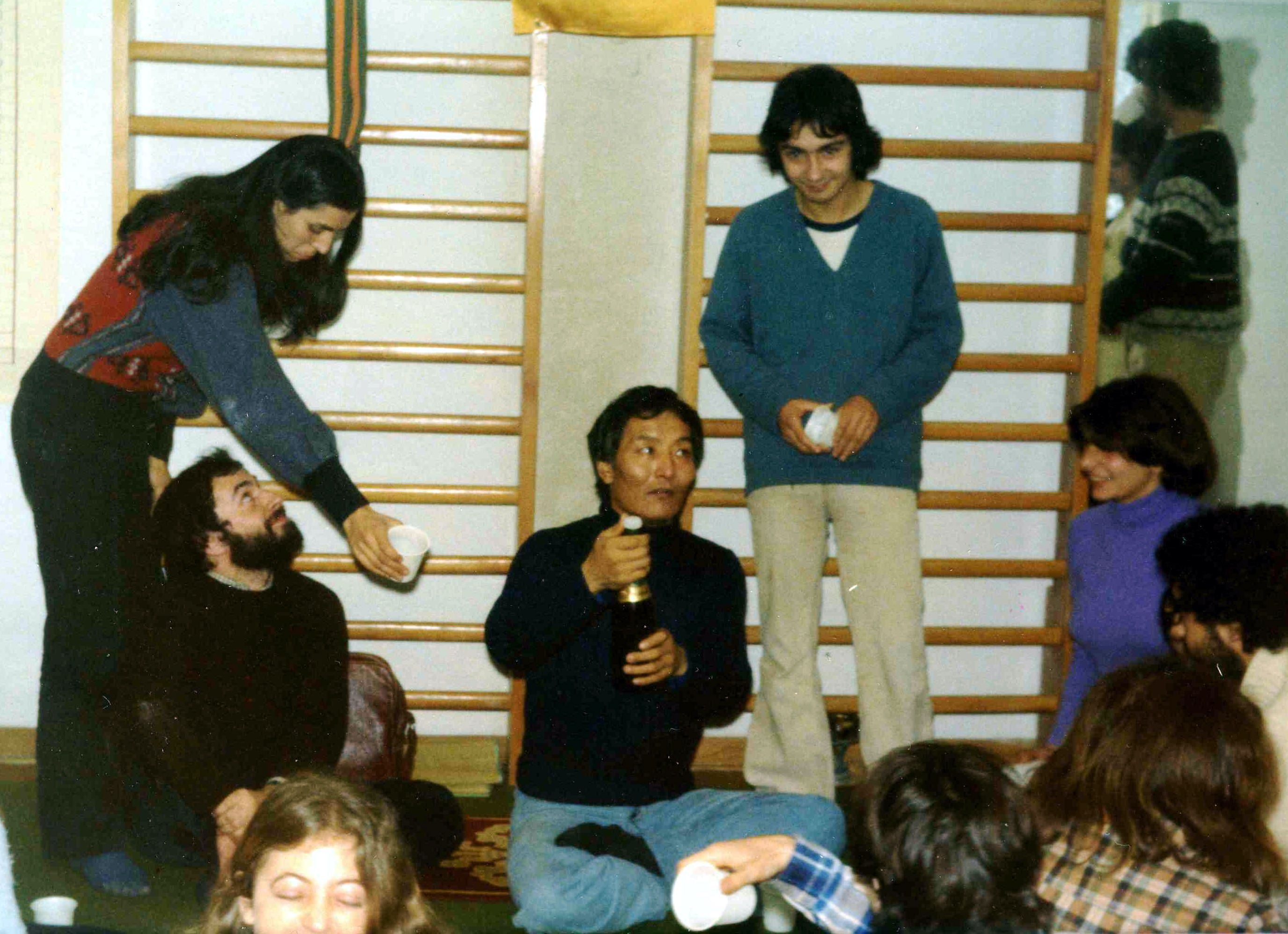

There are many teachings that I learn about directly or indirectly, especially here in Nyaglagar, because it is like being at the source of the knowledge transmitted by Namkhai Norbu to the West through his seminars, books, and spiritual retreats. The master himself seems to find the old enthusiasm of the disciple in reading the texts that the heirs of Changchub Dorje offer him, pulling them out here and there, from their homes and from the library of the temple.

Among them is a small booklet with a red cover, the last one written before his death. It is called “Self-Liberation Through Sensations”, and is entirely devoted to sexual practices related to the control of psychophysical energy. Namkhai Norbu says it is very interesting, and I am naturally intrigued, but I have to content myself with knowing that one day, perhaps, it will be translated. The title recalls the type of teaching to which the text refers. The principle of self-liberation is Dzogchen, the natural state of the individual. Not being a method per se, it makes use of all methods.

The one indicated in the red booklet by Changchub Dorje, before leaving this world, refers to sex, therefore among the most pleasant to practice (although obviously sex is here seen only as a tool for spiritual realization). These are most likely techniques for integrating the strong energy set in motion by the sexual act into the state of contemplation.

It is a characteristic of many Eastern religions and philosophies to use these methods to reach higher levels of knowledge. Many may have heard of the Tao of sex, for example, and think that one must withhold semen by inhibiting orgasm. After leafing through a book on the subject, some might try – very irresponsibly – to put into practice what they have read, thus risking creating serious problems for themselves.

Rinpoche explains that, “Only after years and years of practice, with a close partner and under the guidance of an experienced master, can one master and concentrate the flow of sensations in the right way”.

Integration into the natural state occurs through subtle channels of energy that the practitioner must learn to recognize, and be instructed and guided. The goal is not physical fulfilment but the realization of the so-called union of clarity and emptiness. This is the recognition of the natural state of each individual.

The sexual act between man and woman is also presented as the union (yab yum) of the male principle, method, with the female principle, energy. Method alone cannot lead to any realization, and neither can energy.

Many peaceful and even terrifying yab yum figures fresco the walls of the Nyaglagar temple, indicating the divine nature of these practices of which men have lost knowledge.

All the images of masters and Yidams of the Tibetan figurative tradition offer a visionary interpretation that transcends the artistic level alone, with their rigid repetition of forms and gestures. The temple is almost always empty, and we often go there with Namkhai Norbu looking for the right light to photograph the large paintings that fill every corner of the walls, all created during Changchub Dorje’s lifetime based on his experiences and visions.

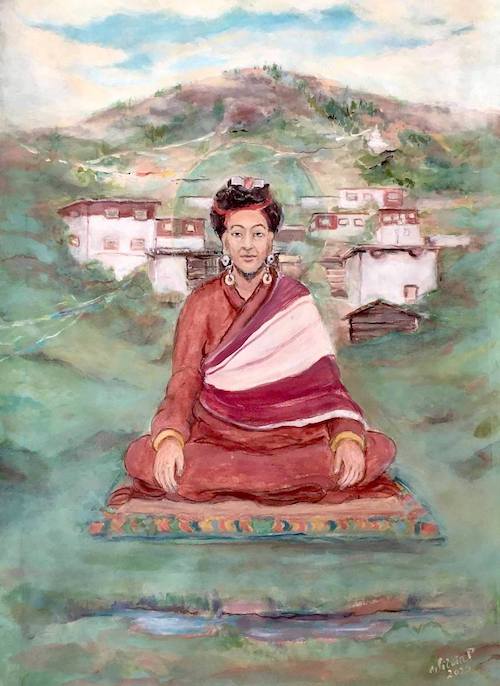

Images from the temple at Changchub Dorje’s village.

One day we finally find the right time to shoot, when the sun beats down from the opening at the top, illuminating the richly colored walls. Most striking of all is the painting of Ekajati. Her body is black and sinuous, with outstretched arms and one shining eye in the center of her forehead. Almost as large as a man, the figure is enveloped in flames and the whole image has a surprising vitality.

Looking at this image, everything else seems to come into motion, like a slow, exciting dance of monsters projected on the walls by an invisible camera. From the ceiling, the light of the sun is dimmed by clouds coming and going, like the psychedelic spotlights of a nightclub, but without music, without noise.

Much more disturbing are the frescoes in the small temple dedicated to the ferocious deities, where the gold-painted figures stand out against the black background and seem to come out of a nightmare. I enter for the first time with a group of children who point to the entrance, a tiny door where you have to duck down to go through, and they invite me to sit on the cushion in front of the lectern and the small altar, as if they were the hosts.

I look around a little, and soon one of the old monks who was a disciple of Changchub Dorje enters. It is the time for the ritual of the guardian deities depicted so intensely on these walls and the monk invites me to stay.

He asks me if I want to accompany him using the drum, while he performs the ritual by ringing the bell, another symbol of energy in the primordial state. The drum is very large and is beaten with a femur, creating a low, deep sound, certainly the one we hear every night.

Very soon I have to interrupt my attempts to guess the rhythm, because – without understanding the language and the moments in which the invocation becomes more intense – I end up dramatising or emphasising the wrong moment and beat the drum quite faintly when the text calls for the entrance and intervention of the invoked spirits.

Many religious practices resemble shamanic rituals because they are undoubtedly its offspring. The search for a relationship with the spirit world stems from a strong and profoundly human need to understand beyond appearances. For Tibetans, dialogue with those entities that we do not see materially but that are in contact with us in a thousand visible and invisible forms, must have its own language, its own access codes in nature itself.

If a dog wants to communicate with us, it uses particular forms of expression. So we use words, gestures, drawings and – above all – the mind, both to transmit and to receive messages. Mantras, invocations, and rituals are the result of the ancient experience of many humans who, before us, felt the same need to communicate and who were unjustly or superficially judged for many years to be sorcerers, or shamans, in a derogatory sense, both by westerners and by Buddhists themselves.

In times long past – this is true, with great ignorance and scant regard for life in many parts of the world including Tibet – animal and human sacrifices were performed (and even today, fortunately rarely, in some corners of the world some are still performed). But then it was thought that in order to gain heaven’s favor the same results could be achieved by symbolically using images and statues, as taught by Shenrab Miwoche, reformer of Tibetan Bön.

Continuing on the path of knowledge, mankind may gradually discover that no chanting, no prayer, but a real state of contemplation is needed to achieve peace with beings of all dimensions.

To be continued

Read Part 1 Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Chengdu

Read Part 2 Background to travels in Tibet

Read Part 3 Derghe and Galenteen

Read Part 4 From Galenteen to Gheug, the master’s birthplace

Read Part 5 On the Road to Nyaglagar

Read Part 6 The Master’s Master

Read Part 7 Waiting for a Miracle

Video of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu in Tibet 1988

Featured image: the damaru of Changchub Dorje.