How I Met Chögyal Namkhai Norbu & An Artist in the Dzogchen Community

Feb 6, 2015

Mariano Gil was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, November 27th, 1961. He grew up in an artistic and musical family. He started formal music education at age 15 at the National Conservatory of Music. After High School he enrolled in Medical School graduating in 1986. He was planning to become a psychoanalyst, when after receiving a scholarship to Berklee College of Music move to Boston to study music. At that point he started practicing meditation in the Theravada tradition, studying with Larry Rosenberg and Narayan Liebenson at the Cambridge Insight Meditation Center and retreat centers. While studying music at Berklee he worked as music instructor, and got some assignments as an illustrator based on his musician’s portraits. In 1993 he met Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, and has been a student since. He took his Santi Maha Sangha Base exam in 1995 and in 2015 became an Santi Maha Sangha Base instructor. Mariano continues to write and perform music in the NY area, shows his paintings and started his first weekly SMS courses in Kundrolling, NYC. He lives in Brooklyn, NY with his son Sebastian, who plays trumpet.

The Mirror: Can you tell us a little about how you met Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, your life, your younger life, and what led you to the teachings, etc?

Mariano Gil: I first came into contact with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu through his books. I was practicing in the Theravada tradition at the Insight Meditation Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts and was attending those centers and going to retreats. I moved to Boston right after graduating as a medical doctor in Buenos Aires, Argentina, when I won a scholarship to study music at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. This was a huge shift in my life. I was planning to be a psychiatrist or a researcher and was interested in neuroscience and psychoanalysis. I was reading philosophy and I was very much interested in the mind. When I arrived in Boston, I discovered the Buddhist teachings and felt at home right away, it was what I had been looking for.

I started going to silent meditation retreats. At one point in these long sitting retreats, I started having certain experiences particularly related to the mind, which was what I was drawn to the most. Particularly observing my thoughts: Are thoughts substance? What are they? Where are they? Where did they come from? I was kind of obsessed with that. It wasn’t something my teachers were telling me about there but it was more of my personal inclination. As soon as I started doing that something opened up completely for me. I started having very strong experiences and my practice became very stable.

M: What methods were used?

MG: The instructions were mostly related to the Pali teachings of the Buddha, awareness of the breath and mindfulness practice. They were very simple and clear and initially I followed them to the letter. That helped particularly with posture and the physical aspect of sitting, and slowing my thought process, which made it easier to start observing the mind. I remember reading Krishnamurti and other different teachers who would say, “observe your mind” and I would think what is this and what are they talking about? Then after doing these retreats I noticed I could do that. At one point I had very strong experiences and then they became reliable and stable and was able to go into shamata much more deeply after doing that…it was like my mind was able to focus without distractions.

So I practiced that way for about six years, but as the years passed by I kept trying to understand that experience with thoughts, which was more related to movement and dropping the object of fixation.

M: Did you talk with your teachers about this?

MG: I did. Yet my teachers, although very helpful, weren’t giving me too many clues to what was happening when observing thoughts, and kept pointing back to this more conscious and effortful practice of observing my breath. I felt that something was opening for me in a way that I wanted to understand better, so I started searching for books…

I would skip all the breaks during retreat and would stay sitting for hours non-stop because once I would enter into a very stable shamata I felt no need to move. It was a blissful experience and I got very attached to it, but I felt I was missing some understanding that could help me move further, or even see my obstacles. So, I started reading and it was only when I discovered Tibetan Buddhism that I found some answers. Initially I had a bit of reservation towards Tibetan teachings because I couldn’t connect to the whole idea of rituals and religion, but when I started reading, I think the first books might have been Trungpa books, Lama Yeshe, Tarthang Tulku, right away they would talk about observing the mind. That really gave me a lot of inspiration. I found out there was a Sakya teacher in Boston, so I went to see him. He was working with very scholarly studies of the sutras and I tried but I couldn’t connect or find what I was looking for there. I was coming from a very experiential practice. In one of those environments I met Malcolm Smith and he had a book and I don’t know why, but I felt like in that book was where I would find my information.

M: And what was that book?

MG: Well initially Malcolm was very protective and he said no you are not ready for this and you first have to learn this and that and I said, “I need to see what that book is.” The book was The Cycle of Day and Night by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. I found the book and I also discovered that Chögyal Namkhai Norbu was alive, I didn’t even know because he might have been a teacher from an historical period, not only was he alive, but he had some students in Boston. So I got the book and started reading right away. This was in 1991.

M: So you were enrolled at the Berklee College of Music at that time?

M: So you were enrolled at the Berklee College of Music at that time?

MG: Yes, I lived very close to the meditation center and would go to the morning and evening sittings and I was really involved, but I started to have a little bit of disconnection and the teacher was not too happy with the questions I was asking. So when I started reading The Cycle of Day and Night I would just have experiences that were very similar to what would happen after hours of sitting during ten day silent retreats, except they were spontaneous, they would just happen. It was like someone was grabbing me by the hand. The book has instructions on direct introduction and not only that, but how to stabilize, that book became ‘my’ book for many years. I have probably read it one hundred times; I would read it daily as a practice.

So I decided to find out more about Dzogchen, found a telephone number to call and Des Barry answered and he said yes there are people in Boston and so I started practicing there. I felt that this was my teacher and there was no going any further and I just felt like that was it, not only in terms of the trust in the teacher but also the teachings themselves. I felt like there was nowhere else to go, that was the end of the line, and it could go so much further, but it was the point of connection. So I found out Rinpoche was coming to Massachusetts and I went to the retreat in 1992 at a high school during a big spring snowstorm. Everything was a confirmation, just being in his presence, but also a lot of things that were very obscure for me, like everything having to do with Vajrayana. I was very intrigued with many things, but for me when I heard Chögyal Namkhai Norbu talk everything became crystal clear; for the first time I understood the difference between transformation and renunciation, and why we do all these things in tantra. What seemed a little exotic before now became very concrete and something that could be applied.

M: Earlier you had trained as a medical doctor and you renounced all that to go towards music, can you talk a little about that?

MG: Yes I went through six years of medical school, in Argentina where I am from, but by the fifth year I had a very big crisis, which, when I look back on it, it seems as if it was almost a break that allowed me to go in to the teachings. Before that I was much more into the mind and very drawn to science and psychoanalysis. I was also interested in music, art, philosophy and poetry.

M: So when you went to medical school you had an experience of what might be called the ‘dark night of the soul’?

MG: Yes, I think it was a combination of things. My best friend had committed suicide when I was about 18 or 19; we studied sciences together and we were both trying to figure out the mysteries of life. We were both very young and idealistic and he was brilliant and I could connect to him very well, so when he committed suicide I was devastated. He had been diagnosed with schizophrenia so that also became an incentive to become a psychiatrist, for me to understand what schizophrenia is and help people. Then I also had a semi-fatal accident coming back from a gig, someone was driving us back and I don’t know why but I had a premonition that something would happen. I was very scared and everyone else fell asleep, and then at one point I see the guy going towards the car in front of us and I think what the heck is going on and I look and the hired driver had fallen asleep so he crashes into the car in front of us. Nothing happened to any of us but I had all the people on top of me, I couldn’t breathe, I got really scared, I panicked. I was on the bottom of the pile of people and it took a long time for us to get up and I couldn’t breathe and so I thought I was dying. I saw the whole thing happening, our car flipping over, and I was saying good-bye… even after the accident I thought I would die and I was waiting for the stars to turn off. It was almost like the accident was sent to me.

The very next course in medical school was neurosurgery. I was already pretty much a hypochondriac because you have to study so much about disease and causes of death; I was the kind of student who would take it all in, all the sicknesses. Some students were the kind that put on their white doctor’s apron and take their distance. I wasn’t able to do that, with the patients or with the studying. I got a little crazy with this. I was also reading very difficult stuff like Wittgenstein, Lacan, Gödel besides the medical literature… it was a mixture of things, I wasn’t sleeping and I would have panic attacks where I would feel I would die. Meanwhile you study a lot take exams and I would have many sleepless nights so I had two months of something very hellish. I would go to a psychoanalyst three times a week, which is normal when you are studying to become one, and when I was feeling like this I went four times a week. Slowly things got better. At one point therapy stopped making any sense. The doctor kept interpreting and I said fine you can interpret to the end of your life, but I am stopping this. I stayed in medical school not knowing which direction I would take. Finally everything kind of calmed down and I graduated.

Two weeks after graduation from medical school, Berklee College of Music from Boston did a ten-day course in Argentina and at the end they gave scholarships. I was already a musician and I was awarded a scholarship, so I decided to take a break and go for a semester or something. I had been playing music from a young age, and when I was fifteen I started going to a conservatory and studied with a great flute master, Alfredo Ianelli, a classical flute teacher. Then I started studying more jazz, jamming and playing out. I was so excited to go to Berklee Music School. I wanted to take a year off anyways, before going to residency, and what better thing than to go for a semester to Berklee. After a semester at Berklee the thought of medicine had not crossed my mind once, so I stayed, and that is when I encountered the meditation center, etc., which all led me to Chögyal Namkhai Norbu.

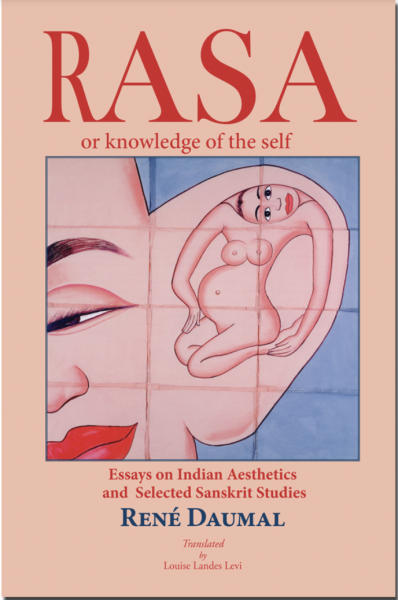

I also had always done drawings and paintings; art is very much in my family. I did not feel as talented as the people around me but I found a way to visually express myself and then in Boston I made a living out of that. I did t-shirt designs for the Berklee College, I did a lot of portraits of musicians in my style, I had some exhibitions, someone saw my work and hired me for a magazine; when I moved to NYC some musicians had seen my drawings and they hired me for an animation company.

M: How did you end up moving to NYC?

MG: All the best musicians I met in Boston were moving to NYC, and I wanted to go too. I graduated from the music school and had been playing out with bands and in clubs since I was in Buenos Aires. Many of the jazz musicians at the time when I was in Boston went on to become very famous and it was a very special time for jazz. Initially I was not playing so much in NYC because I needed to make a living and the visual thing took over; I was doing illustration and computer graphics. Did lots of CD cover art, I also have some private music students and three years ago I started teaching chess in private schools for kids.

M: Can you talk a little about how the teachings have impacted your music and visual art or not?

MG: For me it goes both ways; probably it was the music and the art that opened me up to the possibility of something else which in the end was Buddhist teachings and meditation, and then finally to Dzogchen and Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s teachings. Definitely once I started practicing Dzogchen, I started to realize that a lot of the ideal frame of mind of a musician is that, ideally being completely integrated with sound. For example, jazz can have a reputation for being intellectual, and one can go the intellectual route and one can access it initially intellectually, although traditionally I don’t think it was very much that way. It was coming from the Blues and was very much an oral tradition, which has been lost and maybe that is why many people don’t like jazz, because it has become something else. But when you are performing the music and what is called improvisation, which is also misunderstood a lot, it does not mean do whatever you want whenever you want, it means being very present so you can connect both with your knowledge of the music, the tradition, and also the musicians around you; so that you can respond and something comes very organically, in the moment. So if you are in your head, you cut off from the musicians around you and the audience. Many times I hear musicians who are not practitioners, when they describe their experience they say the state, or selfless, or something that has to do with the moment where they can drop their ideas and it is like they are being played. It is like their fingers are responding to this other thing. As far as visual art, it runs in the family. I have to say I am very much self-taught. I’ve had a lot of interest in “Buddhist” art, and really love the art I have seen in Tibetan Medical texts; I love the way the animals are depicted. I guess I have never had a realistic approach to drawing and I feel there is always something one brings to reality anyway, not as something mathematically perfect or something. There is always a lens. So I have done some of those animals in my own way.

Mariano (right) with Lynn Newdome (left) and Michael Katz (center) after receiving their Santi Maha Sangha Instructor Diplomas in Dzamling Gar, Tenerife, Spain

M: You just became a Base Level Santi Maha Sangha instructor here in Dzamling Gar, Tenerife. Do you want to talk a little about that experience to close?

MG: It was a great experience and taught me a lot. I did the base exam and training twenty years ago. It had been in my mind forever but because of many involvements and becoming a father there were always some kinds of difficulties. I felt it was important to become authorized to help people honestly and correctly. Preparing was a real challenge and a lot of time had gone by, but I was very inspired by studying hard again and using my memory in this kind of way and the challenge of explaining in front of Rinpoche and the members of the Community, was a great learning experience.

At the exams I met fabulous people and we were all very supportive of each other, understanding both the challenge of the exam and the responsibility we have by making this commitment. It was really wonderful. Now I will go back to NYC and Kundrolling. Kundrolling has some financial challenges, but I have enormous hopes for the Community; I have seen some great changes and I feel that the NY Community is in a wonderful place – the energy, there are no fights, everyone seems to be there to help, to learn more and beyond. Hopefully we will get some study groups going on a regular basis. It feels like NYC is an important place, there are a lot of things calling for your attention in NYC, so I think it is important for our center to have something to offer and I think there are a lot of great people there. There are a lot of very talented people in NYC and there is also a Tibetan Community in Queens, so I hope we can get our organization together and collaborate and make the center very alive.