By Fabian Sanders

A talk given on Wednesday February 5, 2025 at Dzamling Gar, Tenerife

This topic about sound and sound doctrines in India and consequently Tibet is the fruit of my personal research. Since I teach Tibetan language, I developed an interest in understanding the roots, the nature, and the doctrines that are aimed at explaining what sound, and consequently language are. In particular also how mantras work and how language can be understood and applied to different levels of practice.

Ancient India dedicated the best part of the last 3000 years to understanding and transmitting sound and its role within the development of the universe. And, I think, the depth, the extent and profundity of the Indian understanding of sound are unmatched in any other tradition in the world.

Understanding the word “universe”

Let’s start from the beginning. First, the word universe should be understood correctly. Nowadays, many people speak of parallel universes, multiple universes, multiverses, and so on, but this is a misuse of the word because universe means “everything” which is all inclusive. So we need to keep to the word in order to have the power to understand the concept behind the word. If we misunderstand the word, we do not get the concept anymore.

So, the universe is understood as a kind of pulsating entity. Its principle is outside and above time and space themselves because obviously, if the universe is contracted, compressed, absorbed into itself, there is no space and no time yet. It’s the conscious principle or divine consciousness which is a sum of all possibilities, nothing else. There is no intention, there is no want to manifest anything. It’s just pure possibility in that sense.

And then at a certain point, because possibility needs to be realized, there is an explosion, like an explosion of wrath, which is a symbol for movement, for going away from the principle. All of the wrathful depictions of divinity have this idea of movement. And this first moment of explosion can be represented as breath, it is prāṇa in Sanskrit or lung in Tibetan. Prāṇa is, at this stage of cosmogony, the origin, the moment in which the manifested universe actually starts to move from subtle states towards degrees of condensation, of diversification. This first movement is instilled with prāṇa or lung. In a way we can say the universe is the breath of the absolute; absolute meaning something that is completely independent, completely free. But however we want to call it, the names that we give are just placeholders. Names belong to a point in the development of the universe where things already exist and because they exist, you can give them a name.

Here it’s just breath and breath is the base, the core, the energy that produces sound. That is not only true for the universe as a whole, but it is true for individual people as well. You can speak because you breathe. You use your breath to blow air through the various organs in your mouth and nose, and actually the first movement of manifestation is breathing out. So in a way, the universe is the sounding breath of the absolute. You breathe out and everything manifests. You breathe in, everything goes back to the principle.

The individual is a small-scale version of the whole universe, every individual in particular humans, because they are somehow situated in the middle of the hierarchy of beings. They are microcosms corresponding to the macrocosms and they do the same thing, for example, they breathe.

Coming back to the principle, to the origin, we have this explosion and prāṇa happens and is the energy putting into motion two things that are the same: sound and light. This is quite complex and is explained by different schools in different ways. It is particularly developed in Shaivism in India. And so sound and light come out as if they were a single thing with the same vibration or movement, prakāśa light and vāc voice or word. These are not gross light and sound, they are never objects of the perception of any eye or any ear.

Light and sound

Also very interesting is how sound and light are explained at this stage. The light is white and the first sound is “A”. It says, for example, in the Aitareya Aranyaka, a Vedic text: “Truly, the vowel A is the whole Word. The latter becomes manifold and varied when specified by the consonants and the fricatives.” White light is the sum, the container of all colors of light. White light is the universal container or principle of all colors.

It is the same with sound. The universe sounds A and we do, too, and to sound A we start with our throats closed, the moment before manifestation, and then we open all our organs, mouth, jaw, tongue, with just the vocal chords vibrating. This is expressed in the ‘‘yige cigmai do’, the Sutra of the Single Letter, in which the Buddha explained the whole of the teachings as being “A”.

In the previous Vedic text I mentioned, when it says that the “A” becomes manifold and varied when specified by the consonants and the fricatives, it means that these initial sounds start to descend into multiplicity. It starts to have obstacles which cause it to fragment and become multiple, the seed syllables.

But very often it is expressed that from the initial sound A various seed syllables start to separate as fractions of this complete sound. For example, the seed syllables of the five elements start to resonate or decimate from this initial sound, and being vibration, being energy, they solidify. They collect around them the constituents of the element itself. It is like the sound vibrates and by means of this vibration, which has a kind of agglomerating function, it gathers all the potentialities of the five elements initially. This is at the very subtle level. The elements have a color and a sound and these things start to separate, become varied, distinct.

This is particularly the language that we can find in the tantra, both in India and in Tibet. For example, there is a quote from the Guhyagarba tantra, which says: “The tathāgatas then expound the inner meaning of the letters, referring to the uncreated syllable A on the level of the buddha body of actual reality Dharmakāya, to the forty-two syllables that emerge in conjunction with it on the level of the buddha body of perfect resource, Sambhogakāya, and to the words and letters they form on the level of the buddha body of emanation or Nirmāṇakāya”.

The development of syllables

At this level, we are still in the very beginnings of the universe and see the syllables develop. Most of these seed syllables are made up of a consonant part, a kind of closure of breath; then there is a vowel, which is the actual ‘life’ of speech. Finally, there is a reabsorption which is represented in these seed mantras, in these bīja mantras, as by the anusvāra (the ‘after sound’) or the M, which is represented in script by the dot on top of the letter, which represents the pure nasal sound. And this sound is a reabsorption and cessation of the breath and sound. The sound comes back into the inside. And this is exactly the same as what occurs for the whole universe, beings and so forth, birth, life, and death. It is a beginning, expansion, and reabsorption. Everything happens this way, not only in the life of beings, but also breathing, the pulsation of blood, the heart starts expanding, compressing, re-expanding, recompressing. And everything which moves happens in this way.

So, to come back to the way manifestation occurs, this energy, this sound, which is still very far from being an object of the ears, differentiates, or some limitation happens.

For example, when talking about speech, and letters or language and grammar, the Jaiminīya Upaniṣad Brāhmaṇa, another ancient Vedic text, says that the innermost nature of all vowels (svara) is associated with Indra, representing the life force of speech because prāṇa fully enlivens them. While that of the spirants (ūṣman) is associated with Prajāpati, these are continuous sounds produced without closing the mouth. Prajāpati is the father or the origin of all beings. Occlusive consonants (sparśa, ‘touch’) are associated with mṛtyu (death), these require blocking prāṇa, closing the breath.

This analysis of the vowels, the spirants and the consonants constitutes the whole repertoire of the alphabet by which we can form all the words needed to represent all phenomena.

The inner sound of phenomena

And now a very interesting thing comes to my mind. It is the idea of things forming around sounds: from seed syllables, we have further articulation, further complexity. And around this complexity of vibratory energy, phenomena aggregate, pulling the various elements towards them to produce a phenomenon. That is the basic idea of the function of sound within the universe – particularly in certain expressions of Indian thought, that a thing is such because it contains a sound that causes it to compose. It is like having a piece of paper with iron filings and a magnet underneath. When you move the magnet, all the iron filings align in relation to that magnet. That is an image that might clarify what is meant when it is said that sound aggregates phenomena.

For that reason, phenomena have an energetic core, a vibrational core that is their inner sound. This is then used to name them, so in the idea of the Sanskrit language, things are called that way because that is their inner reality, vibratory reality. For example, fire is called in a certain way because that is the true sound within that phenomenon. In other words, it is not an arbitrary attribution. It is the true name of fire that you are speaking. And in that sense, from this idea, all the practice and theory of mantra comes, because mantra is something that is not directed to a meaning or to some mental process of thought. But rather, mantra is a vibrational element, an energetic element, completely separated from meaning, and is supposed to vibrate harmonically with the world, or more importantly, with the inner world of the practitioner. The practitioner contains within him or herself the whole universe. And by using mantra that is the vibration specific for this myriad of aspects that beings contain, one can control them, can harmonize, can elevate them in terms of mingling one’s mind, one’s awareness with that higher reality.

And this happens in groups of things. So that is also a very interesting aspect of Sanskrit in my opinion. For example, you have a root sound made up of a particular collection of mostly consonants. By differentiating this root with vowels and so on, you can capture the particular aspect of a group of phenomena that is related, or that is defined by a specific inherent characteristic. For example, the Sanskrit root M and N is used to refer to many things that are human. You can already see that even in English, HUMAN. In India the first human being in our world is called “MANU” , “M” and “N”. Humans are called manuṣya which means those who come from Manu, the first human. But also more interestingly, MANAS is the human mind. Humans are those who are characterized and defined by having a predominant use of the mind, mind in this inelegant aspect of being the endless stream of thoughts.

From these various ideas, also descend the concepts of power formulas, which are a kind of application to a lower level. Now you want something, you have the formula. And Siddhas, for example, can control vibration in a way that the phenomenal world obeys them. They have power over voice, over words, over things that obey their commands. There are lots of funny stories concerning the Mahasiddhas.

Mantras in Sanskrit

In any case, it is easy to understand how mantras must be in Sanskrit because they harmonize themselves to some aspect of reality: that is the sound and it cannot be changed. Many people these days want to translate mantras, but that’s completely mistaken in the sense that it’s not the point. Mantras do not have a relevance to the understanding mind. They are just vibrations, energy. An etymology of the word “mantra” says that MAN is the mind. TRA means to protect, so mantra protects the mind because it absorbs the mind and prevents it from going here and there and endlessly being attached to or hating things and so on and so forth by that way perpetuating one’s samsara, one’s cycle of rebirth. So let’s say that the word used for the mind for communicating is a secondary application of the theory of language. It is a use of that idea for the practical use of communication, of symbolizing things.

So at this point, in the quote from the Guhyagharba, the Nirmanakaya, this sound becomes letters and words. When the discursive mind that is not aware uses words, they are detached from that primary reality which they represent and they start to be used in the mind for representing meanings and to be the instrument of the discursive mind, the tool by which the thinking mind represents the world to itself. This is very interesting and just the surface of a very deep and profound science that encompasses the whole of the Indo-Tibetan tradition and by which it is clear that also for Tibetans the sacred language always remains Sanskrit, because this quality of being a real or natural language is recognized. For that reason, mantras must always remain in Sanskrit.

Also, interestingly, since we are now in the world of the mind, we are already very far from the first prāṇa outburst of the principle. We are in the gross dimension of manifestation and at that point, we have all sorts of phenomena around us. In order to understand the world, we do not only have a need for words. Words are just isolated items by which we try to represent something to ourselves. But these things that are out there, they have relationships, causes and effects. Verbs or actions are done. Someone does the action. Someone receives the action and so on. All this interaction and movement cannot be represented by words alone, but must be represented by grammar. Grammar is the thing in language that allows us to organize things in time, in space, in relations, causes, effects. So grammar is also one of the sacred sciences in India, and consequently, in Tibet.

Tibetan as a sacred language

Tibetans consider Sanskrit to be their sacred language, and Tibetan to be a reflection of the sacredness of Sanskrit. From a certain point of view, Tibetan as well can be understood to be a sacred language. And for that reason, most Tibetan masters are reluctant to translate practices into other languages. They consider that practice texts need to be in Tibetan, mantras in Sanskrit.

Tibetan language has, in my opinion, at least two reasons to call itself a sacred language and to call the study of the language a sacred practice. First of all, when Guru Padmasambhava went to Tibet and was invited to pacify and harmonize the land in the face of all these gods, godlings, spirits, and so forth that were wreaking havoc, one of the things he did was to go step by step all over the land and subdue these beings. And although he was not Tibetan, he was from Oddiyana, tradition has it that he subdued those beings, made protector deities or guardians out of them and wrote down texts by which they can be ritually controlled. By which their vow of obedience can be renewed, and can be utilized by practitioners to have a good relation with these beings. All the practices of the Guardians and so forth, more or less come from Padmasambhava or some of his followers and they are in Tibetan.The point is that these texts, which are considered to be powerful, are in Tibetan. They are in themselves powerful in terms of the sound, the words that constitute them and they have power on these beings. So for that reason, it is a sacred language.

Another more scholarly reason is the fact that so-called Dharma Tibetan actually was fine tuned to be able to perfectly represent the Sanskrit Buddhadharma in Tibet.

I covered a lot of things but I hope I have introduced some ideas on how sound is actually a pervasive part of reality, both in very apparent and outer ways, but also in inner and profoundly essential ways for beings in general and practitioners in particular.

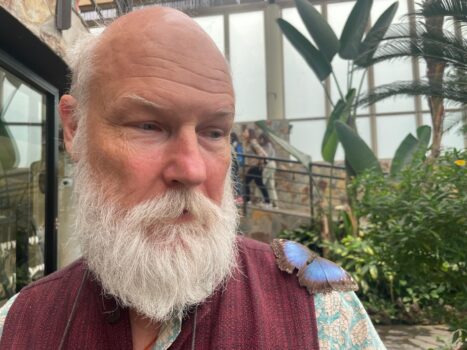

Fabian Sanders was born in Italy from German parents. With an instinctive attraction to ancient and Oriental traditions, he started traveling and studying Chinese and Sanskrit at the Oriental language department of the Ca’ Foscari University in Venezia, Italy where he obtained a Ph.D. with a thesis on the life and lineage of the IX Khalkha Jetsun Dampa Khutukhtu. Separately he studied Tibetan and started to teach it at the same university, a position he held for twelve years. He currently works as a translator and teacher of classical Tibetan under the school for Tibetan Language and Translation of the Atiyoga Foundation founded by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, his main Master. He has published several essays and articles as well as the first classical Tibetan language grammar in Italian.