By Christian Correnti

Giorgio Dallorto is a friend for me, often a guide, so I don’t think this will really be a typical “Dzogchen Artist” article/interview and hope that the editorial staff won’t insist on it.

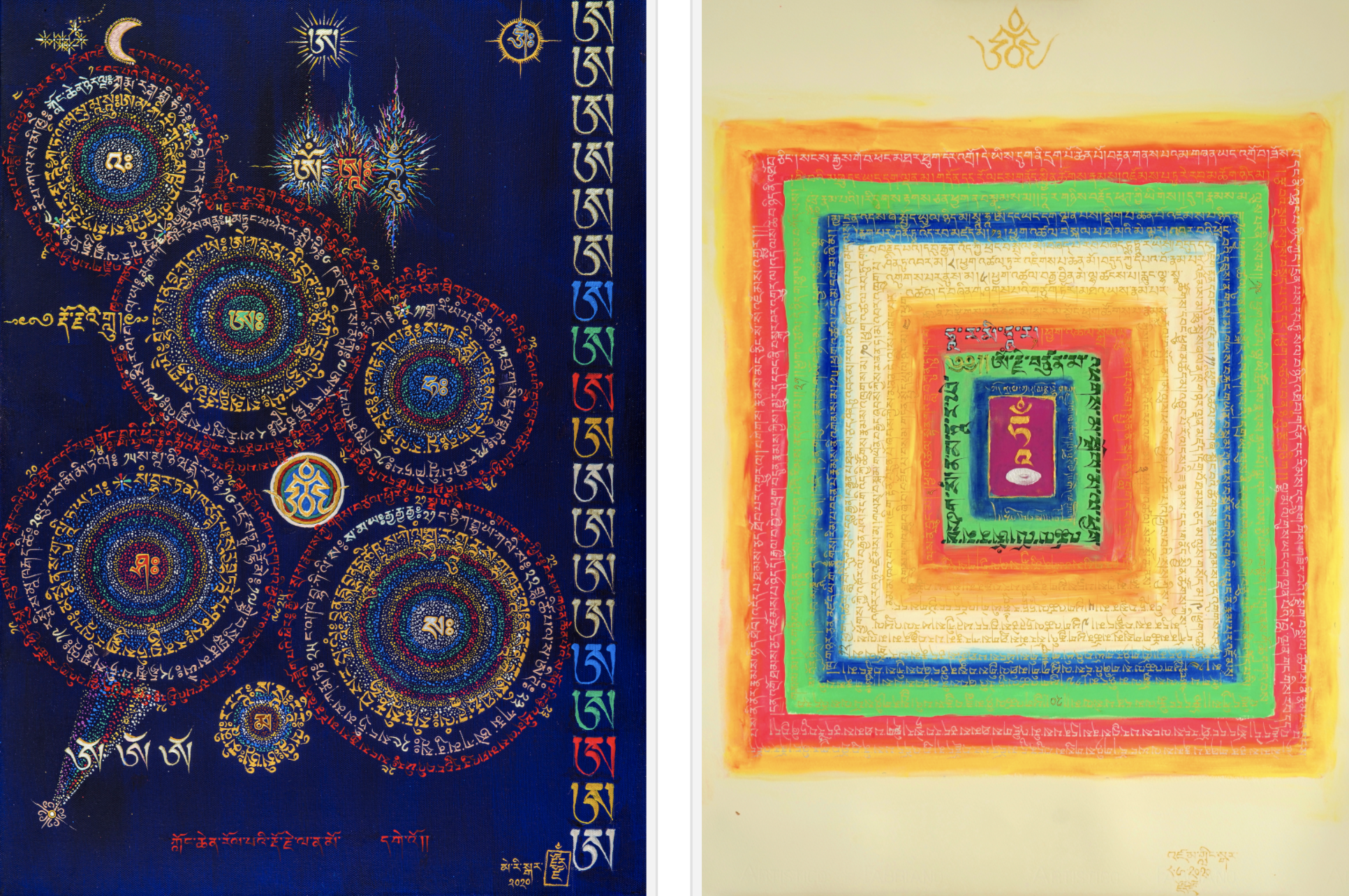

This morning I went to his home. The entrance was filled with August light that, here on Mt. Amiata, is the color of gold, the same gold that is echoed in a spiral around the Song of the Tantra of the Dance of the Vajra, majestic, on a blue background, leaning against the fireplace, in front of the desk. One of his latest works that really catches the eye and mind.

Books, thangka, paintings, calligraphy, statuary, I don’t know where to start Giorgio’s story. A vast and multifaceted culture, ranging from history to literature, from art to numismatics, from religions to philosophy and which embraces West and East in a clear and strong vision. I could start by saying this, but it would only be one way. Other, better ones can be found.

In many subjects he was mostly self-taught, but he was able to fully explore them, make them his own, as evidenced by his library and his rigorous character. Giorgio is ingenious but has the patience of the humble; he knows how long it takes to learn a technique, how much practice must be undertaken to reach a goal, be it material or higher.

His curiosity, his reading, his love of Himalayan culture and fascination for Tibetan Buddhism led him in the summer of 1978, in his early twenties, to meet Chögyal Namkhi Norbu, and this epiphany undoubtedly changed the course of his existence as man and scholar.

His wish to learn, his love of teaching and philosophy combined with that of art and its applications soon led him to study the Tibetan language with Professor Fabian Sanders and later calligraphy with the artist-calligrapher, Tashi Mannox.

Calligraphy soon became a deep passion. “Many reasons pushed me to study and practice. First of all the difficulties: I have always liked challenges. And then this is an area that is not very sought-after, I would say almost a niche, to which few, even among professionals, dedicate themselves.”

25 Spaces of Samantabhadra (left) and Arya Tara practice (right). Photos by Antonio Ruffaldi and Lesya Cherenkova.

Thus the circumstances were the best: the challenge, the study, the effort, the practice, the passion and the desire. I wondered what else is needed for an artist to be born? This question has as many answers as there are artworks which you feel drawn to and part of. I think I am not mistaken in saying that in Giorgio’s case that this ‘something’ must be sought in the Teaching.

Writing a Song and writing it with skill, giving it movement on a canvas or solid wood, giving it the right color, adding stars and decorations to the words, symbols, being inspired by the Teaching, is not transcribing and decorating. It is praying, practicing and finally making art. And perhaps the most interesting thing is that in Giorgio’s case, making art was not, is not, a priority, but, judging by his works, an indisputable goal.

But how does an Italian from Turin start writing Tibetan, and most of all why?

“I started by copying my Master’s texts written in beautiful handwriting for us students. As a study method, copying Practice texts has always helped me to memorize words and to fix the graphemes as symbols, so learning spelling from the beginning was a necessity for Practicing, a means that over time has also transformed into something more.”

Into so much more. I knew that Giorgio had this great passion. I knew that he had been dedicating a long time to calligraphy for years and that his goals had undoubtedly become high, or, meticulous and demanding as he is, he would never have given Rinpoche some of his calligraphy, as happened on more than one occasion. But never, ever could I have imagined that calligraphy would have taken over so much of Giorgio’s existence.

A world made up of colors, symbols, materials, words, Practice. Something that arises perhaps by chance as a challenge, but that grows and develops from the Teaching, becomes art, mixes with the West, with influences from Kandinsky to his passion for ancient Western miniatures, for iconography. It is possible that this Western encounter with the art of Tibetan calligraphy, while leaving the Eastern tradition intact may help a Western public increase their understanding and serve as a material support for the practice. Even by those who know nothing about it. In fact, the levels of reading that you can have of one of Giorgio’s works are infinite. As many as the eyes that admire it and the moments in which they do.

Philosophy is not my field and perhaps not even art. I certainly couldn’t talk about Teaching. But anyone who has met the Master knows how many wonderful seeds he planted in each of us. I like to think that many of these are growing strong and prosperous in each one of us. It is clear, to those who observe Giorgio’s works chronologically, that after Rinpoche’s passing these have multiplied, have grown, become precious, I would like to say like offerings, like a flourishing tree. The last months of quarantine then provided everyone with a time we were not used to, a time that Giorgio was able to magnify in a truly abundant and inspired artistic production.

After showing me works of considerable size (mostly made of wood) that occupied a large part of the intimate and joyful room where we had a long conversation, Giorgio went to get something from another room. I felt satisfied, partly overwhelmed, I would say. I had too much to talk about and my problem was indeed how to synthesize and convey my emotion because you certainly can’t talk about art. Art must be enjoyed directly, which is why I recommend going to the Aldobrandescan Castle in Arcidosso and for this reason I would like Giorgio to set up an internet page to exhibit, at least virtually, all of his works. So, while I was lost to put together some thoughts, he arrived hugging some large yellow and orange folders that were obviously heavy.

Giorgio is resolute, attentive, determined. A no-nonsense man. He doesn’t need to talk about it, it shows. And so, while I was still wondering how long it would take to complete a 50 by 70cm work, five or six sheets of this size paraded in front of me, and they were only the first. Beautiful thick paper, handmade or smooth, natural colored or white on which, freehand, he draws colors and gives material thickness to songs, mantras, stars and decorative elements.

It is these smaller, more intimate works that I would like to mention. Perhaps because I see them as something that could be enjoyed in my home. Perhaps because I come from a simple culture where private devotion, a canvas to gaze at, a thangka, or a prayer to read give comfort and security.

And in particular I think about this wooden tablet recovered from the Merigar Gönpa after its restoration. A piece of wood that breathed the incense and prayers of Rinpoche and our own. Three vertical lines in Uchen characters that recite the Song of the Vajra. Characters made of gold in relief imprinted with a pen nib on the ultramarine blue that covers the grain of the wood. On each calligraphic work there are small abstracts of the Teaching, I would say a synthesis. In fact, the spaces that Giorgio leaves empty are rare, as calligraphers have done traditionally and the way those who have something to say and know how to do it like to do. Thus on this small wooden tablet (76x14x4) we also find the letter A inside a Thigle made up of the colors of the five elements, the three letters OM A HUM of the three enlightened states of the Buddha (Body, Voice and Mind), and again the six letters of the Six Self-Liberated States, up to the dedication to Master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu.

“I may have approached calligraphy as a lazy pupil, which over time has become a precious tool for studying and deepening the Practices. Ultimately it has become a belated but profound homage to the great calligrapher and Master who was “the king of the Dharma jewel of the sky”.”

Giorgio thus closes our conversation while I still, like you, have questions and a lot of curiosity. But to these works, in addition to the pleasure of the eyes and the joy of the mind, I owe an even more important thing, the right harmony to practice.

I conclude with a quote from Kandinsky taken from On the Spiritual in Art. ” This capacity of profound depth is found in blue …, if we allow the blue (in any desired geometric form) to work on the mind. The inclination of blue to deepen is so strong that its inner appeal is stronger when its shade is deeper. The deeper the blue the more it beckons man into the infinite, arousing a longing for purity and the super-sensuous. It is the color of the heavens just as we imagine it, when we hear the word heaven.” This quotation describes more than any other words what I felt while admiring the canvas with the six Thigle containing the Song of the Vajra and the 25 Spaces. A Song, but also a painting, illustrated to a large extent by that small star at the bottom left from which the powerful rays of a rainbow emerge iridescent.

It’s late, it’s almost time for lunch and Giorgio accidentally opens the folder with the pieces that he’s working on, but unfortunately, to see these, we’ll have to wait!

Translated by L. Granger

[The quotation by Kandinsky from On the Spiritual in Art was taken from the Internet Archive funded by Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Library and Archives of the first complete English translation of the book.]

Featured photo: Giorgio Dallorto and his calligraphy of Arya Tara practice. Photo by Lesya Cherenkova.