Our International Dzogchen Community includes members from many diverse walks of life, professions and interests. There are many who are dedicated to the field of healing in its many aspects, whether mental, physical, or spiritual. We invite the healers in the Community to send us their experiences, observations and advice to share with our readers.

The first article in this series is from medical doctor and psychotherapist Gino Vitiello from Naples, Italy.

The theme of forgiveness has long been ignored by psychology because it is considered to be a ‘religious’ topic; it is only since the 1980s that its importance in the psychotherapeutic as well as the spiritual field has been recognized. In order to understand its different aspects it is useful to compare it to its opposite – rancor.

If we think we have been treated wrongly or unfairly, it is normal to feel angry, and if we do not move past this feeling, it becomes rancor. Rancor is the building up of anger that can become a real poison for the mind and the body. There is evidence that chronic anger produces not only emotional damage but also damage at the somatic level. But if rancor makes us feel bad, why is it at times so difficult to free ourselves from it? Most probably the answer lies in our ego, although here we should make a distinction.

Ego is a Latin term that means ‘I’. Freud defined the ‘I’ as the identification with one’s person, the awareness of one’s self, and this obviously has a positive value. What in psychology is defined as “valid Ego” is essential for the quality of our lives.

Here, however, I will use the term ‘ego’ to indicate that exaggerated form of the ‘I’ that brings us to be totally centered on ourselves, on our expectations, and on our own fantasies and fears. In fact, the more exaggerated the ego is, the more it is vulnerable and susceptible to being hurt. The more it is centered on itself, the more it loses contact with reality and becomes the main cause of suffering for oneself and often, if it involves people with a lot of power, for a lot of humanity.

Rancor continually brings us back to what hurts us and prevents it from healing. The main path to healing is forgiveness although it is really our wounded ego that does not want to heal. Our ego finds it unfair to go beyond the hurt and wants satisfaction: “Why should I forgive those who did or said this or that to me! It is better to stay painfully yet righteously resentful.”

If we wish to understand what forgiving means we have to clear away many prejudices.

- Forgiving is above all an intentional choice that goes beyond the spontaneous emotional response to something that has hurt us.

- Not forgiving blocks us from overcoming a trauma and makes our suffering more deep-rooted.

- Forgiving is therefore a volitive act that may also arise from the awareness of the suffering that is produced by rancor.

- Forgiving does not mean condoning the action because it is addressed to the person, not to what he or she has done. Clearly we may wish that amends be made, that apologies be given, but this may not happen and should not stop us from choosing to forgive.

- Forgiveness cannot be imposed and is not ‘do-goodism’ or justifying unjustifiable behavior. If a person is an enemy we have the complete right to defend ourselves, to keep our distance, but without hate. The Buddha taught that we will not be punished for our anger but by our anger.

- Finally, forgiveness does not necessarily lead to reconciliation. This will be possible only if the other person accepts their responsibility, although this does not always happen or may not be possible.

Another important aspect is forgiving ourselves as our ego may not only be hurt by what is outside ourselves but very often by the frustration of not being who we wish to be, of who we would like to be. How many times have we been troubled by moments when we have embarrassed ourselves, when we have not shown ourselves as we would have liked to appear.

Our ego does not like our limitations and makes us want to be other than what we are. This is related to what the Buddha – when explaining the nature of suffering – called “the craving for existence”, or wanting to be more. This does not mean impeding the path of evolution but it is not really possible if we start with a false self.

In fact another subtle aspect of an exaggerated ego is shyness, or not exposing oneself for fear of being judged by others. Then there are people who like to say that they are severe with others because firstly they are severe with themselves. This is also a typical egoistic position, believing oneself to be right and without faults.

When we recognize that we have carried out some actions that we are sorry about, we often develop a sense of guilt. However, according to a concept arising from Gestalt psychotherapy, a sense of guilt is not a significant emotion. If we analyze it, it almost always contains an unconscious dose of anger towards the person to whom it is intended which is different from the suffering arising from their actions, it rarely involves a desire for forgiveness, and doesn’t help to alleviate the suffering. In fact it often creates mechanisms of self-punishment and makes things worse.

The work of forgiving should begin by observing ourselves and recognizing and accepting our human imperfections in order to discover the many ways in which the ego works to create suffering for us, whether it arises from rancor or remorse.

The way to dissolve these problems is particularly important when we are moving towards the later part of our lives in order not to carry such a heavy burden as our consciousness prepares to leave the physical body.

Luigi Vitiello

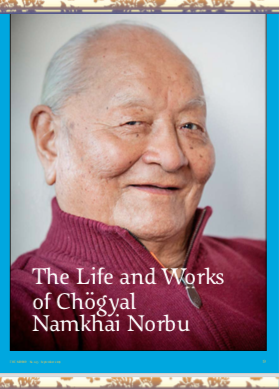

A student of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu since 1977, Luigi Vitiello has a degree in medicine and trained as a psychotherapist at the European School of Functional Psychotherapy and then followed Gestalt training. He is enrolled in the Register of Psychotherapists of the Order of Doctors of Naples.

He is a Yantra Yoga instructor and a meditation teacher, lives and works in Naples and Arcidosso, and holds conferences and courses on these topics in various Italian and European cities.

Photo by Edith Casadei

You can also read this article in:

Italian