February 25, 2014

Dagther from February 21-25, 2014

Today is our last day of this Dagther meeting.

I want to thank you all for coming here and giving importance to this conference. You know very well that Santi Maha Sangha, Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance, all that we are applying and all that we are teaching in the Dzogchen Community, is very important. It is not only for passing time. For that reason it is also important to try to do this perfectly.

Any kind of teaching has its base, its characteristics, and its principle. We should go with that, otherwise we lose the real sense of the teaching. I’ll give the example of when I was working in the university in Italy. Many people asked me to teach about the Buddhist tradition; some asked me to teach something about Vajrayana. I’ve studied Vajrayana and therefore I know it. If I want, I can explain Buddhist Hinayana and Mahayana too. I studied them all for many years. I know them very well for explaining. But I always said, “I am not a teacher. I am still a student. I want to study and learn. Here I am working in the university.” I never accepted to teach people because I know teaching is something serious. It has its principle. No important teachers told me I should teach now, so I didn’t feel like doing it.

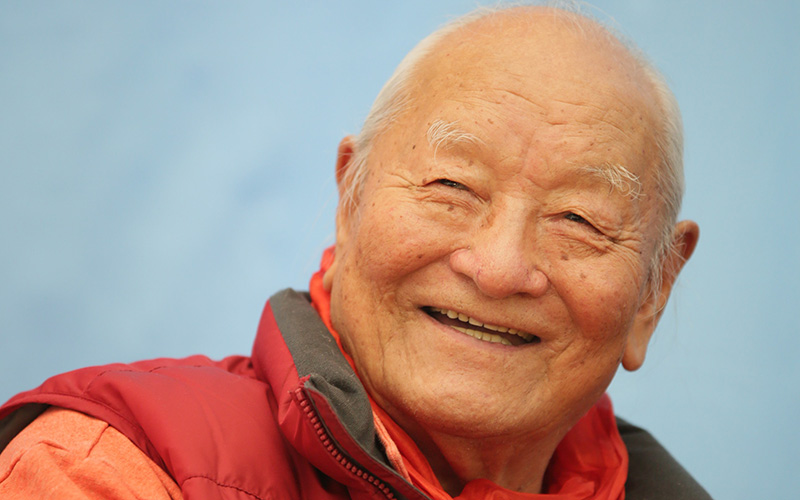

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu with the instructors of Santi Maha Sangha, Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance at the Dagther Meeting Dzamling Gar, Tenerife, February 2014

Then a person also came with letters for me from His Holiness the Karmapa. He was saying, “There are two of my Kagyüpa centers. You go to teach there.” I replied, “I am sorry. Firstly I don’t feel like teaching; secondly I am working for a living here. I should work to eat and to live in this society. If you don’t do anything how can you live? I am working in the university. This is my job. I don’t have much time to go around. I am not going to teach.”

I received a letter from His Holiness the Karmapa a second time. He was thinking he was something like my owner because I received recognition of being a reincarnation from him. When you have this kind of connection they order you, they ask you to do things and you should obey. I also replied also to that letter saying I couldn’t go because “…firstly I have no time because I’m working in the university; secondly, if I go to your center I don’t know what to teach in the Kagyüpa tradition.” I am not an expert of the Kagyüpa. I received some Kagyüpa teachings of Mahamudra, etc. from Kangkar Rinpoche, who was a teacher of the 16th Karmapa. But it is not sufficient that I received those teachings and then I teach. So I said, “I am not going to teach” and I refused.

There were not only these requests, but also many people came. For example, I remember one day a man arrived and said, “I have come from India. I am a student of Kongtrul Rinpoche.” That was Mario Maglietti. He said he wanted to learn from me because Kongtrul Rinpoche told him to do that when he returned to Italy, because Kongtrul Rinpoche and I knew each other and used to communicate. I said, “I’m sorry. I am not a teacher; I am not teaching anything.” A few months later Paolo Brunatto and his wife arrived. They insisted that it was very important for them to follow teachings from me. They had followed Abo Rinpoche and so on. I said, “I am not really giving teaching. I am not a teacher.” They kept insisting and one day they came to see me in Naples. I didn’t know what to do. I asked them if they had some practice books of the Kagyüpa teachings they had followed. They showed me the Guruyoga practice books they had. I explained their books to them a little and told them to try to do the practices they had received. That was all.

For many years I never gave teaching, because I feel it is something serious. We cannot just do it anywhere we happen to be – it is not that way. [We should] pay respect to Buddha, and pay respect also to the transmission. This is the reason I wasn’t giving teaching or doing anything [related to it], and had also refused the requests of the Karmapa twice.

Then one day a Gelugpa geshe arrived and did a kind of retreat near Rome. He was very expert in philosophy and the Gelugpa tradition. Of course many people went there to learn. Then I thought all these people who are a little interested in Buddhism are going to learn Gelugpa. That is good; it is OK to learn Gelugpa, but then the Karmapa asked me many times to teach something of the principle of the Vajrayana with the final goal of Mahamudra and something like the teaching of Dzogchen, saying it is much better than only teaching sutra philosophy etc. Then I thought maybe we should do something, otherwise I would feel sorry later, really, also that I hadn’t obeyed the Karmapa.

At that time I was ready to go to Switzerland on holiday. Laura Albini had come to me many times saying we should do a retreat. She also had a Kagyüpa dharma center that the Karmapa had given a name. It was only a name; there was nothing else. It was only her house. Some people, such as Enrico [Dell’Angelo] and others used to gather there sometimes. This was called a Dharma Center of the Kagyüpa. There was another similar one in Milan – but there was nothing concrete. So I thought it was better to do something now. I told Laura Albini that if she would organize it, we would do a retreat when I returned from Switzerland and I would give some teaching. This is called working with the circumstances – doing something when it is necessary. When I came back from Switzerland Laura Albini had organized a retreat near Subiaco and I gave a retreat. That was the first retreat I gave and I gave Dzogchen teaching. I gave Dzogchen teaching because these people were interested to learn from me. In my experience, in my life, I have studied and learned sutra, tantra and Dzogchen and I feel Dzogchen teaching is the essence; we must learn Dzogchen teaching.

I applied in that way and so I thought that maybe I needed to teach that also for them, to do benefit for them – not because I want to become a teacher and be called a teacher – no. I am not interested and have never been interested in that, since the beginning.

I started to give Dzogchen teaching – Dzogchen Semde, not Dzogchen Upadesha. Today, if teachers give Dzogchen teaching they always give Dzogchen Upadesha. At first I also followed that traditional way. There is a very important teaching called Jetsün Nyingthig. In our epoch originally Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo gave it to Adzom Drugpa. Adzom Drugpa gave it to many students and also wrote a commentary on it. I received this transmission from the son of Adzom Drugpa. I am interested in that teaching. It is very essential and very nice. So I thought I should start to give this teaching. This is how the Dzogchen teaching developed.

Later, when I had been going around teaching for a year or two I discovered that for most people Dzogchen just remained only a very good idea. When we explain the Dzogchen tawa, point of view or the base, we say we do some kind of practice and stay in contemplation and then we think it is sufficient. When people learned a little about how to do Guruyoga, etc., they were satisfied and thought they knew about Dzogchen and the real nature and everything. I saw that most of my students were remaining in fantasy. It was really not sufficient. Also I had some dreams about it.

Then I thought, “What should we do?” I thought there are three series in the Dzogchen teaching: Semde, Longde and Upadesha. I received what is known as the Nyingma kama, all the transmissions of the Semde, Longde and Upadesha from Nyercha Rinpoche, one of my teachers.

Most people receive all these transmissions in a more formal way. If we receive an initiation in the formal way we think that is now OK. If there are some instructions and the teacher reads them, we receive them and we are satisfied. I too received Dzogchen Semde and Longde in that way. Nobody taught me how to apply the practices. It is not because I was in an unfortunate situation; it is because this is the tradition in our epoch.

One of the oldest monasteries in East Tibet is Katog Monastery. At first the founder, Kadampa Desheg and his students studied Dzogchen Semde, Longde and Upadesha and they were more concentrated on applying them. In that period there were many teachers in the Katogpa tradition. They were called Trungpa – not Trungpa Rinpoche of the Kagyüpa. Trungpa was almost a kind of title given to those who had studied and become expert. There were many generations of Trungpas. Trungpas are not reincarnations; they are teachers whose intellectual knowledge and application of practice correspond. Then they are called Trungpa.

Trungpas developed for many generations and many of them wrote commentaries and instructions of the Dzogchen Semde, Longde and Upadesha. We still have many of these kinds of books. But later, more or less at the time of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, the first Jamyang Khyentse, Jamgön Kongtrul, throughout this period when there were many teachers who were reincarnations, everyone concentrated more on reincarnations. Also at Katog monastery and the tradition of Trungpas gradually disappeared. The origin of all the present important lamas, the Katog Rigdzin reincarnations, is the Trungpas.

When all was concentrated on reincarnations it became more important to give initiations and to go around doing rituals to benefit the monasteries, so that they grew to be gigantic. That was sufficient. They no longer developed Dzogchen Semde and Longde. But the transmission of Dzogchen Semde and Longde was not interrupted.

For that reason today if you want to receive Dzogchen Semde and Longde you can go to a Nyingma monastery and make a request. They say there are teachers who give transmission of the Nyingma kama. Nyingma kama is not only terma. Kama is a tradition of [teaching passed down through] a long lineage. Most people don’t even have any idea of what kama and what terma are. For example, I have some relations in India. They are not stupid people; they know very well how to read and write. Maybe they haven’t studied philosophy very much but they have sufficient ordinary knowledge. A big Nyingma monastery in South India invited Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche to give teaching there of the Nyingma kama. One of these relations of mine told me Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche went to give very important teachings on Nyingma karma. “What do you know?” he asked me. “What does karma mean?” He was thinking two ways: it was to do with Karmapa or something related to Karma Kagyü. He didn’t know about kama. Even the sound of [the words] karma and kama is different. That’s an example. If people are ignorant, they don’t know about Dzogchen Semde and Longde. I thought, if I want to teach, Dzogchen Semde is very important.

Compared to Dzogchen Upadesha, one works much more in Dzogchen Semde and also in Dzogchen Longde. Then I thought that we needed to do a Dzogchen Semde retreat. But even though I had that idea, though I had received all the Dzogchen Semde transmissions, I had no knowledge of how to do it. Now, for the benefit of the students, I studied Dzogchen Semde. For months and months I took all the Dzogchen Semde texts and read and learned the precise instructions.

Then we started to do the Dzogchen Semde retreat and I was explaining. I didn’t just explain it because I had received it; I was using my mind and my understanding. When I was reading the books I was comparing them with the real sense that I had understood from the explanations of my teacher Changchub Dorje. We did Dzogchen Semde retreats for many years. When I observed my students after a year or two they were not living in a fantasy like before; it was becoming more concrete. After that we knew that Dzogchen Longde is very important. I had received very precise transmissions of Dzogchen Longde too. That wasn’t missing. But we didn’t have very precise instructions. I received those transmissions from Ayu Khandro. She spent all her life in dark retreat but she gave those instructions in the traditional way. Maybe she didn’t receive them in a particular way either.

That is an example of how I worked with Dzogchen Semde and Longde and bringing something concrete and integrating them with the real sense of the Dzogchen teaching. For years and years I tried to understand a little more how we should continue the global Dzogchen teaching, how that teaching should be. That is related with my experience.

With my practices and so on of course I received more clarifications about these things, because I sometimes have doubts about many of these points. I am not always a hundred percent sure of everything. When I had doubts and these kinds of problems my dreams developed and I receive many Longsal teachings – these teachings that we have. The Longsal teachings are on how to go ahead globally with the essence of the Dzogchen Semde, Longde and Upadesha integrated. Afterward I had no doubt. I knew very well how Dzogchen Semde, Longde and Upadesha should be integrated because I received all the series of the Longsal teaching. This is the principle of the Longsal teaching.

I also did it in a very concrete and precise way. I told you how I did the dagther when I wrote the Mandarava text. My translator Adriano knows how I did all the Longsal teachings in the same way, because he reads all of my dreams: everything about how they started, how they developed and how they finished. In this way we make sure a hundred percent. It’s not just that we write them down one day and then think this must be it: Amen. No, it’s not like that.

The Dzogchen teaching that I am trying to make you understand is very important. You are following the teaching from me. When you are following the teaching from me you must try to do it in the correct way, the best way, not doing it in your personal way. I am not saying you can’t invent things – you can, but don’t do it with my teaching! If you want to follow and use my teaching, try to do it perfectly!

For that reason I started to do Santi Maha Sangha. From the beginning I prepared it for how we continue the teaching for the future. It is not sufficient that I go to a place today where there are some students and I explain and they are satisfied or I am satisfied. That’s not sufficient; it is relative, but the future is more important. Even though it’s a hundred percent sure that we’ll all disappear from this globe after a little while – nobody will remain – but the teaching and transmission of Dzogchen must not disappear together with us. Particularly a precious teaching that has a really serious function for all sentient beings, such as the Dzogchen teaching, must not be lost.

Even though many teachings have the title “Dzogchen” they are not always Dzogchen teaching. Since we are living in dualistic vision people always think dualistically about everything.

For example, the first time we went to the United States, Fabio, Andrea, Enrico and others, a group of us went to New York. When we arrived there we saw publicity saying that Dudjom Rinpoche would be giving Dzogchen teaching. Dudjom Rinpoche is a fantastic teacher. He really has knowledge of Dzogchen. But what the organizers were doing was in the relative condition, not in the real sense, and not what Dudjom Rinpoche was doing or the way he was doing it. Then some of my students, including Enrico and Fabio, went to the teaching and we discovered that Dudjom Rinpoche was giving teaching on a text by Longchenpa called Chözhi, Four Dharmas. Gampopa originally wrote this. Gampopa was a Kagyüpa. Kagyüpas concentrate on four important arguments. Gampopa explained the details of these four arguments. Gampopa didn’t invent them. They were developed in the Kagyüpa from Milarepa and from that original teaching.

When we follow [Vajrayana] teachings they usually say there is the Ngöndro and then the main practices. Putting these together makes two Dharmas. Lo chö su drowa means “the mind is directed to the Dharma.” For the explanation of this there is a description of the Six Lokas and how Buddha explained the Four Noble Truths, the first one being suffering. To overcome these kinds of problems The Four Mindfulnesses are indispensible: knowing which kinds of suffering exist in each of the Six Lokas: the devas, human beings, pretas, etc. When you receive this kind of teaching you reflect that you are one of the sentient beings in [each of the realms of] samsara and then you think, “This is very heavy. We must liberate from it somehow. In that way we direct our mind to an interest in Dharma.

Gampopa’s explanation of that, called lo chösu drowa, is very detailed. That is the first point. The second is chö lamdu drowa. It is not enough just to be interested. What do we do? We take refuge, cultivate bodhichitta, and so on. Then the Dharma is integrating in you. First your mind is directed toward the Dharma and secondly you integrate it in you. The very detailed explanation of this is the second point. The third point is about how to apply according to your capacity: high, medium or low. If you have low capacity you know very well that if you do not behave in a perfect way, if you do negative actions, of course you’ll produce negative results and the consequent suffering. At least, knowing that, you do your best. If you have a little more capacity than that you can also understand how your physical aspect is related to your energy and also how your mind is related to your energy; how to coordinate [body and energy] so that there will be some possibility to control your mind. If you have a little more capacity than that you can understand that mind works on the relative level in time and space and we need to go in the direction of the nature of the mind. The nature of the mind is beyond suffering and all these kinds of problems.

Giving this kind of information makes us realize that it is important to go beyond mind. Now you have this idea but you still don’t know how to go beyond mind.

Then there is trulpa yeshe, meaning illusory vision manifests as wisdom. When you are really applying [practice] even though you are in dualistic vision, you are in it in a different way. In the Vajrayana you transform negativities and emotions and they manifest as wisdoms. You gradually develop how to apply in that way. In the Vajrayana, there are more explanations: in the different kinds of Tantras there is information on many different methods you can use, by receiving initiation and instructions and then apply the development and accomplishment stage and then we can have that possibility [to go beyond mind.]

Finally there is lamgyi trulpa zhiwa, which means making peace, pacifying dualistic vision. When we are applying methods like transformation methods and so on we don’t remain in dualistic vision in an ordinary way. For example, even though we are in dualistic vision we know very well that this is unreal. We are living in unreality. Just as Buddha said, life is like a big dream and we know life is unreal like a dream. This [gradually] becomes more concrete. Particularly, when we receive a method of transformation in the Vajrayana it is not something stable. If it were really stable nobody could transform. Transforming means we are in time and space and there is the possibility to transform. Also we receive the method of transformation: the development stage and the accomplishment stage. When we really apply that everything is finally in the Sambhogakaya, in the pure dimension and we no longer remain in the dualistic way of thinking, “This is a pure dimension, that is an impure dimension.”

As long as we have the concept of the integration of the two stages: the development stage and accomplishment stage we are not being totally in the final goal. When we are in the state of non-duality it is called the state of Mahamudra. This is the final explanation of Gampopa, the most important teaching of Mahamudra: “in that state.”

Dudjom Rinpoche was giving these teachings, but they were not complete. If he had given them all completely there could also have been Dzogchen teaching at the end. Longchenpa didn’t explain in quite the same way as Gampopa. Longchenpa took the example of these four arguments and then explained them dealing with the characteristics of the teaching of Dzogchen, Anuyoga and Mahayoga – a combination of these three yogas. The finality of these is the state of Dzogchen. But Dudjom Rinpoche gave teaching on the first two arguments, not the third and fourth. In the information for his teaching it said he would give Dzogchen teaching.

Dudjom Rinpoche taught the first two: Directing the Mind to the Dharma and How to Enter the Dharma by applying refuge, bodhichitta and so on – not the third and fourth. Even though the word Dzogchen was in the title of the information it was not Dzogchen teaching. It doesn’t mean Dudjom Rinpoche never gave Dzogchen teaching, but in these circumstances he was not giving it. Many people said they went to the teaching of Dudjom Rinpoche and received Dzogchen. You can discover you didn’t receive Dzogchen teaching. This is an example: it is very important to understand the real sense of the teaching.

I am always telling the practitioners and teachers, always start with your three existences. Even if you just want to talk with someone, you should remember, we have body, speech and mind. We are living in the relative condition within the limitations of what we perceive with our physical senses. We don’t see the energy level. We have explanations and we are learning something about the energy level. It is important to remember that when you apply the teaching by yourself and when you work with other people; then it will become something concrete.

You remember, when I prepared this Santi Maha Sangha I also explained it and gave courses of Santi Maha Sangha. We already have publications of the books of base, first, second, third and fourth levels and many people have studied them and they say, “I did the first, level second level…” But what does it mean, Santi Maha Sangha? You must remember well! Santi Maha means Dzogchen. This is not in Sanskrit language; this is in Oddiyana language. In Sanskrit we don’t say Santi Maha; we say Maha Santi. The grammar of these languages is different. In Sanskrit the adjective is placed before the noun and in Oddiyana language it is placed after it, just like in Tibetan. We can understand how the words were used in the Oddiyana language from the titles of the texts of the ancient Dzogchen teaching.

Santi Maha means Dzogchen. You shouldn’t think Maha Sangha means Big Community. Some people have that idea. It doesn’t mean that. Santi Maha means Dzogchen. Dzogchen means our real nature. You know that, no? The word Sangha means Community. It is also used in Sutra and Vajrayana teaching—all teaching. [In Sutra] we take refuge saying Buddha, Dharma Sangha.

In the Sutra teaching it is considered that Sangha is four monks or nuns. If there are only three it is not a Sangha. To receive a formal vow in the Sutra style there must be four monks present. The eldest of these is called the neten. This is not a teacher, not a guru in the way it is considered in the Vajrayana. If you want to discuss something you talk about it with the elder one, because four people can’t talk all together. The one who takes this responsibility is called the neten. When you are taking a vow, for example, the neten reads from a book. He asks questions like:

“Are you the son of businessman?”

You say, “No.”

“Are you the son of metal-worker?”

“No.”

There are many questions of this kind, because if you have to continue to do this kind of work to support your family you cannot be a monk. They are not asking these things because you will not be accepted if you are this kind of person. It’s not like that. There is a reason. It is know whether you are really free to be a monk or nun. If you are responsible for a family and you become a monk, who looks after the family?

In the end he asks:

“Is everything you said true?”

“Yes.”

Then the elder one reads the explanation of what you should do to receive the vow. He doesn’t give transmission. This kind of transmission doesn’t exist in Sutra. That is what Sangha is in the sutras. There can also be many monks or nuns in a Sangha.

In the Vajrayana we transform everything into a pure dimension so we use dakas and dakinis. Dakas and dakinis doesn’t always mean beings flying in space. When we use the words dakas and dakinis we have pure vision – not impure vision. If we have impure vision we accuse people, saying: You are not good. I know; or, I heard you are doing these wrong things: number one… This is not pure vision. Some Vajrayana tantras say the Vajrayana samayas are infinite. In the Mahayana and Anuyoga there are detailed explanations of specific samayas, saying which are the most important, less important and so on. For example, in general, Tibetan practitioners of the Anuttara tantras such as the Hevajra tantra and the Guhyasamaja tantra, have fourteen most important samayas, which they also read every day when they do pujas of Hevajra or Chakrasamvara. We know them by heart. There are verses explaining each of them one by one. These are called the root samayas, the main ones that we need to respect and keep. When we do Vajrayana practices we recite or sing the hundred-syllable mantra of Vajrasattva, combining mantra, mudra and visualization to purify our samaya. This is in the system of Vajrayana and it is also used in Dzogchen and Anuyoga.

There are many rules in the Sutra system and also in the Vajrayana; but to go to the essence – practitioners should go to the essence, we can’t do everything in detail – Atisha, who was a very famous Kadampa teacher, gave an example: if you want to practice the essence of the principle of Hinayana, you know you should not do anything directly or indirectly that creates problems for others. This is not only for Hinayana practitioners. It is something also Dzogchen practitioners should keep in mind, and should have the presence not to do actions that could create problems for others. We integrate this. This is the teaching of Atisha. He explained that the essence of the Mahayana is doing benefit for others. In the Mahayana that is related with intention: if we have a good intention then everything is good. If we notice we have a bad intention we change it into a good intention. That is the essence of Mahayana.

Also Dzogchen practitioners should remember not to create problems for others directly or indirectly and also if there if there is a need to do benefit for others we are ready to do our best.

There are so many samayas in the Vajrayana, how can we keep them all? Atisha explained the continuation of pure vision. Only enlightened beings can really have totally pure vision just like Buddha Shakyamuni. Then there is no cause of negative visions. But we are always thinking and judging and creating infinite causes of impure vision. So we must try to increase pure vision. If you have pure vision there are no problems. Pure vision means you know that in a real sense all the sentient beings you see in front of you are Dakas and Dakinis. Why do I see them the way I do? I am in illusory vision like in a dream. I know very well that a dream is not real. When I wake up it doesn’t exist concretely. Atisha said that having this kind of knowledge is the application of the essence of Vajrayana.

It is the same way when we are doing practice. Some people say. “Oh! I’m doing practice like Simhamukha or Guru Tragphur and I am thinking there are negativities and I am eliminating and destroying them.” This is dualistic vision, isn’t it? We must not go into dualistic vision. For example, if we transform as a deity we transform into a pure dimension not an impure dimension. When you transform into Guru Tragphur, for example, your dimension must be a pure dimension. Even though we are in a pure dimension, in the relative condition, in our mind, in our knowledge there is negativity that [being in the pure dimension] eliminates. But we are in dualistic vision in this pure dimension.

Many years ago one of my students in Naples told me she had learned well how to do the practice of Simhamukha. I had said that if you have negativities you can overcome that problem by doing Simhamukha practice. She said she was doing the practice very often. One day she told me she was very angry with her father and she beat him while shouting the mantra of Simhamukha. I was very surprised. That is an example. Some people don’t have this kind of knowledge.

I also remember once when I was in Chicago someone said they had received an initiation of Vajrakilaya and they asked me how to do the practice. They showed me their book and I saw I had never received that particular practice so I said, “I’m sorry, I can’t explain that.” They said they had asked a lama and he had said you transform as Vajrakilaya and in front of Vajrakilaya Mahakala manifests holding a phurba and Mahakala beats all enemies with the phurba. I said I have no knowledge of that. I couldn’t say it was wrong. I don’t know. It is better [to say that] isn’t it? We can’t behave as if we are omniscient. Many different kinds of methods of practice exist. We should pay respect. But this was not my way. I never learned that. It’s very important.

That’s the reason why we are training Santi Maha Sangha. Many people have learned the first second and third levels and so on. We do examinations of Santi Maha Sangha. Our teachers also did examinations. We must know whether the students have studied well and whether they know well or not.

Sometimes some of the students, teachers, when they are doing examinations, say they don’t know the Sanskrit and Tibetan names and words perfectly. That is relative; it’s not really the main point. The main point is their understanding – whether they understand the argument or not. Language is relative. In the Western world we speak Western languages. Sometimes you remember the Tibetan terms and sometimes you don’t remember, but if you know the substance this is more important. For example, I never remember the names of some Westerners I very often have contact with. When I see the person I remember who they are but sometimes I don’t remember their names. It is not so easy for me because I was born in Tibet and grew up with knowledge of Tibetan culture. That is an example. For Westerners it’s not always easy to learn Tibetan and Sanskrit names and terms.

But it’s not good if you ask a person to explain an argument and they are ignorant of it and don’t know how to explain it. Then you can discover this student doesn’t know Santi Maha Sangha even though they did examinations of the different levels. For that reason we also did teachers’ training examinations. In the beginning I had the idea that if someone had studied and had done the practices of Santi Maha Sangha of the first level, maybe they would have the capacity to teach other people the first level, but I discovered they were very far [from being capable of doing that]. That is why we did Santi Maha Sangha training of teachers. That is why we have eighteen teachers of Santi Maha Sangha here of different levels. Also the knowledge you are studying and training is a little different.

It is important to know that the principle of being a teacher of Santi Maha Sangha is becoming a person who is really integrated in Dzogchen teaching. When you are dancing the Dzamling Gar Dance in the third stanza I am saying, “Ati gongdön ranggyü la dril dang. Ati means the real the state of Dzogchen; gongdön means the real sense of Ati; ranggyü la dril means integrated in you. This is what we should do. If you have done that, even if you are not very expert in many books of Buddhist Sutras and Tantras, etc., you are nevertheless becoming good Dzogchen practitioners. We need to be Dzogchen. It’s not sufficient that only our real nature is Dzogchen but that we are being in Dzogchen. That is why we are doing Santi Maha Sangha. I hope very much that Santi Maha Sangha teachers become that way.

In the relative condition we have so many things. Once I talked about not only Santi Maha Sangha but also about the many practices we use in the Dzogchen Community, particularly the three kinds of Tun in the Tun books, for applying practices of the transmission in the Vajrayana, Anuyoga and Atiyoga styles. Tun means applying a sitting practice for a limited time. Some people say they want to be good Dzogchen practitioners so they do a Short Tun or Medium Tun every day. I reply, “Very good! I’m happy you are doing that.” But this is not the principle. Even if you don’t do practices from the Tun book every day, if you are in the state of Guruyoga even for a very short time, I am very happy – much happier than if you are doing practices from the Tun Book.

The Tun Book is necessary because it is a way we can collaborate. When many practitioners meet together what should we do? We should do something useful. What is the most useful thing? It is being in the state of Guruyoga together. We also do a sitting practice involving body, voice and mind, because these practices are like that. We are not just walking about, eating, drinking and talking about useless things for hours and hours. In that way we waste time. Any time we have a possibility to be together we do something useful: being together in our state. This is just like a practice of Guruyoga. Even though there are mantras, mudras and visualizations in any kinds of formal practices, if we are Dzogchen practitioners we always do them governed by the principle of Dzogchen knowledge.

For example, when we do the mantra of the Purification of the Five Elements we apply visualization of each element one by one. This means we are using our mind and applying practice in a more relative way, but at the end, when we say, “SHUDDHE SHODANAYE SVAHA,” SHODANAYE means we are in a state of contemplation with the clarity of a completely purified dimension. Then we relax in that state. That is an example of how we are integrating. There is the possibility of integration in any kind of practice. That means we are governing that practice with the principle of Dzogchen.

That is why, it is important to go to the essence. I often say that if, one day all my students are only doing Guruyoga, saying “A” and relaxing, I’ll be very happy, even if they are not doing any formal practices. But if someone says they are not doing any kind of practice – only saying “A,” that is not sufficient. You should deal with your existence of body, speech and mind in a state of Ati. Ati gongdön ranggyü la dril dang. That is why we are singing and dancing.

I hope very much that our teachers, knowing that principle, will follow and pay respect to how the teaching really should be, remembering that we are doing it for the future; it’s not that you are not doing it for me. Some people think they are doing service to their teacher – that I told them to do that. Maybe I didn’t say anything; this is not my job. But I am helping; you are becoming my students and I give you advice, saying maybe this is a better way to do this or that. It is very important that you become responsible for yourself, instead of thinking that I am responsible [for you].

I did my job my way for many years and I’m still continuing to do it. You can collaborate with me. What is important is that you should continue the teaching in the correct way. You might say, “I’m responsible for myself,” but then, if you do it your way and you are not paying respect to how the teaching should be, that is not good.

When we are living in our time we have to be aware that there are always two aspects: one aspect is the relative condition; the other aspect is related to our real essence of the teaching of Dzogchen.

If you are doing anything about the teaching, giving teaching, giving instructions, including also Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance, everything is related to the Dzogchen teaching. You should remember that – the Dzogchen teaching that I taught. If you understood and discovered it in you, then this is the state of Dzogchen. These kinds of practitioners, collaborating, being together is called the Dzogchen Community.

Remember that what you are doing is related to the Dzogchen Community and the Dzogchen teaching. If you are not doing it this way, if you are doing something personal in your own way, this is not connected with my teaching. In this case you are outside. You must remember that.

The Dzogchen Community is not something like an organization of policemen, checking and controlling everything. Being responsible for yourself means knowing how to deal with the Dzogchen Community, how to continue the Dzogchen Community. You are responsible for the Dzogchen Community – not yourself. Then you should work. If there is something to do or to organize in the relative condition it is not that it has to always be under the control of the Dzogchen Community, no. This is not the correct way. You remember when I explained the basis of the Dzogchen Community at the beginning, I said the people belonging to the Dzogchen Community – that means people who feel, “The Dzogchen Community is my family, I belong to this.” If some of these people want to form something like a cooperative – that was an example I gave at that time – if a group of three or four people of the Dzogchen Community want to form a cooperative to do some kind of activity, any kind of thing to create income of course they would communicate about that with the Dzogchen Community and if they need some help of course the Dzogchen Community would help with that. But you do it knowing that you belong to the Dzogchen Community, and if you eventually earn money, you will contribute some part of that to the Dzogchen Community. I started that way from the beginning. You can read the explanation I wrote.

We are living in time. At the time I explained all this things were different from how they are today. At that time there were no computers, there were no mobile telephones, for example. At that time they said something special has come out for sending messages but we couldn’t yet communicate by computer. At that time I only had these kinds of ideas. In our society nowadays there are many kinds of things for organizations.

Sometimes it is necessary to organize things like Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance. You should remember then there are two aspects: the aspect of the relative condition and the aspect of dealing with the principles. That is why we have classes on different levels: the first level, and the second level. For example, in the Vajra Dance the second level is the Dance of the Vajra and the first level is the Dance of the Liberation of the Six Lokas and the Dance of the Three Vajras. The first level is good for presenting more openly but it is not good to present the second level openly because it is related to transmission. We should pay respect to that. It is serious.

The way of introducing is also very, very important. There are many ways of introducing any kinds [of practices] including Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance. For example you can explain that they are for harmonizing our physical body, because we are living in dualistic vision. Our body is an aggregation of the five elements and when they are disordered we can receive negativities because we don’t have sufficient protective energy. You remember how many times I explained these things. You can explain this also to people who are not Dzogchen practitioners, who are not Buddhist practitioners. But anyone can believe there is a physical body and in the physical body there exists energy. You can explain that Yantra Yoga movements and also Dance of the Vajra are beneficial for that. You don’t need to explain their relationship with Dzogchen and what Dzogchen is, etc. There is no reason to explain that.

But if people are a bit more interested you can explain a little more – how movements are related with breathing, how the mind is dependent on energy; how energy is dependent on the physical level and we how we can work to coordinate them. Everybody can understand that. People who want to go really to the essence can understand.

Also in Yantra Yoga there are many positions and so on. It’s not necessary to say you cannot do them openly. You can explain and do them, but in Yantra Yoga there are many pranayama practices most of which are related to practice and transmission. We should keep them a little more private. But there is no reason why you cannot do more general breathing practices.

For the organization, etc., if you are organizing [things] in different countries, you know the laws are not the same in all countries: in Spain there are Spanish laws, in Russia, Russian laws and in America, American laws. We cannot do a universal type of organization. In this case, a person who is interested and qualified – not just anybody who wants do some job like this – can make understand and also communicate with the Dzogchen Community and organize these kinds – also [forming] a kind of association. In the different countries there are no limitations [preventing] you from doing things like that.

But when you do that it should not become a personal position; you shouldn’t say, “I want to be a teacher of…” and then live from these activities. This is egoistic. We are the Dzogchen Community. I am saying any kind of teaching I gave belongs to the Dzogchen Community. You should remember that. In this case you can develop that way.

I am also thinking that it is very important we need [to check] all these kinds—how the Santi Maha Sangha teachers are teaching, how we should do that. Sometimes people are jumping onto a too high level. That is not good also for the Dzogchen Community people. We should pay respect to everything in a precise way. [For them] and also for the Yantra Yoga and Vajra Dance teachers we need to organize some kind of guidelines. We don’t have this yet; it doesn’t exist. For that reason many people don’t know what they should do. To make these guidelines we need to use the opinions of the people. Yesterday everyone talked about his or her opinions. I want someone to make and give me a report of these; I don’t need every word they said, just the more essential and important points. Then we can observe and check to see how we can prepare guidelines. Once the guidelines are prepared we should apply them in that way. Then there will be fewer problems in the future. Otherwise, I am being a teacher with my teachings and sometimes I feel as if I am riding on a wild horse. I don’t know where I’ll be thrown away. Then I don’t feel well.

Also sometimes I feel that way with my teachers of Santi Maha Sangha. I want to say that openly. So, please! Be careful! I don’t want to fall anywhere.

We do our best. I am collaborating with you and you try to collaborate with me and with the Dzogchen Community and with everybody and really do our best so there will be something very precise for the future.

What Enrico explained yesterday is very true because we have two aspects. One is the worldly situation. We must be very well aware of how the relative condition is and how we should work with the circumstances. The teaching should be in accordance with that. But we should not fall into only (be concerned only with) this. We have Dzogchen teaching. You know how important Dzogchen knowledge and teaching are, not only for us but also for all sentient beings. We don’t only just believe that – No! We discover it. It is something concrete. We know this is precious and we must not loose it. For that reason we need to have that awareness. That is why I say this very short version: please try to be in the state of Guruyoga! People ask me:

What practice should I do?

Guruyoga.

Even if they ask me ten times I always reply:

Guruyoga.

After Guruyoga, what should I do?

When you are not in the state of Guruyoga, you are in dualistic vision – present, not distracted, present.

When you are being present what should you do? Work with the circumstances. How are the circumstances? Yesterday is not today; today is not tomorrow.

Westerners have (the habit of dwelling in the past) the attitude (of thinking things like) “Many years ago I did something wrong and now I feel guilty.” You are thinking about that when you go to bed instead of sleeping peacefully and dreaming something interesting. You’re always thinking, “I remember these (bad things) I did,” etc. Next day when you wake up you feel nervous. This is not good. It’s useless. Past is past. Forget it! If you want to write a book about what you did two years ago, then you try to remember and write it down – but not even that. If you did something wrong, it is past… If you think that many years ago you did something wrong and you do a practice to purify it, then that is good. In any case practice is good for purification. You can dedicate it for the past, future and everything. But for the rest, don’t think too much about the past. Be in the present!

If you are being present in the present you can enjoy your life. Life is not so bad, as long as you are alive; then one day you’ll disappear. Until that point we enjoy, we do our best, relaxed. That’s the first thing. Why don’t we manage to relax? We are always thinking, “This is this; that is that. Yesterday someone said…” We remember these things again and again and get angry or upset. Forget it and enjoy yourself! If you don’t manage to enjoy yourself come here when I’m singing and dancing and come to sing and dance. It helps you instead of thinking useless things. If you have your principle of knowledge of Dzogchen, singing and dancing is a practice. If you have knowledge there is no difference between singing and dancing and doing [any other kind of practice]. If you have no knowledge you should now cultivate a different way of thinking, then it helps just a little. If you have a bad stomachache or headache you need to take an aspirin and it can help a little in that moment. That is similar to doing this kind of practice. If you have that knowledge you don’t need to go in that direction. In our life everything related to body speech and mind is in the relative condition and we can integrate everything. When we are integrating with circumstances we are being present; we are not distracted.

Someone might say, for example, “In the circumstances I am going to kill a pig.” But you know that killing a pig doesn’t correspond with your presence. You know very well that if you kill a pig it will suffer, so you don’t do that, do you? Being present means that. Always some people say it is very difficult to be in the present. If you never tried to train in that of course it’s not easy. Some people say they tried for two or three days to be present but it was very difficult. We are always distracted; we are not being present, so it’s not easy to integrate always being present. It’s not easy but it’s also not so difficult. It would be difficult if we had to practice the way Milarepa did. If you were told you had to go on a mountain without food and stay there for months and years, that is difficult but trying to be present is not so very difficult. If you have time you can do training. Also when you are working you can try to be present. You can always learn. Some people have no understanding of being in [the state of] knowledge. I always give a very simple example of being in [the state of] knowledge: it is similar to driving a car. If you know how to drive a car, when you are driving you can talk with people and look around; you have all these possibilities. You also have the possibility to think and judge at the same time as driving but you are not distracted, otherwise you would cause an accident. We should learn to b present in the same way in our life. We don’t spend our whole life driving a car; we do so many things and can learn step by step [to be present while doing] everything. I often ask people to sometimes dedicate one or two hours to this so that it becomes easier and easier.

A Dzogchen practitioner is never distracted in any moment. Even when you are talking with people for hours, it’s not necessary to be distracted; be present! That is what you should learn: being present – particularly our Dzogchen practitioners and our Dzogchen teachers. Teachers must be present and then, knowing that, they can give a good example to students, to people who are learning. This is a practical way in the Dzogchen teaching. It is very important.

Sometimes tensions develop between people. Why do these tensions arise? It’s because of not being present. If you are being present you know very well what Buddha said. He always said repeatedly that everything is unreal; that life is just like a dream. It is not sufficient just to know these words and talk about them; we must apply and be in that knowledge. If you are being in that knowledge, your way of presenting, even while you are talking with people, your way of seeing and the condition is changed. It is very important for all you people to remember this.

Transcribed and edited by Nina Robinson

Final edit by Susan Schwartz