Multicolored Impermanence

by Premila Van Ommen

In the week of prayers and global celebrations of our late beloved Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, the Drepung Kongpo Khangtsen monks, belonging to the great Drepung Loseling Monastery (also known as the Nalanda of Tibet for its high academic standards), visited our London center, to create a sand mandala. We were honored to have these esteemed visitors spend a few days from December 5-8, 2019 building a sand mandala in Lekdanling until its contents were swept and poured into the waters of Victoria Park in a dissolution ceremony on the final day. This was the first time to view a sand mandala construction at Lekdanling for both regular and new visitors, who were warmly welcomed by the prayer flags at the entrance. For many, it was an opportunity to witness firsthand such a creation and query the monks about this practice.

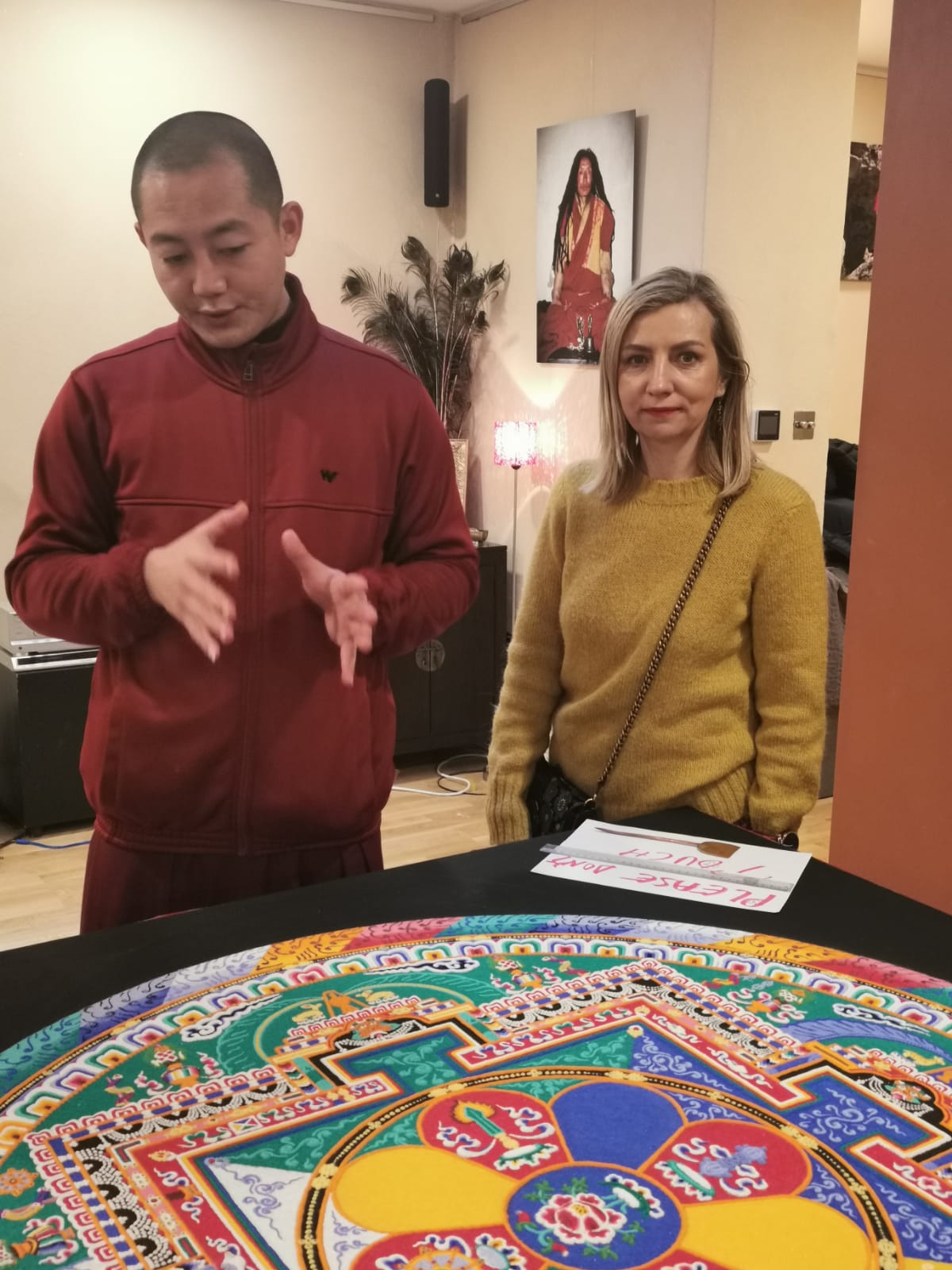

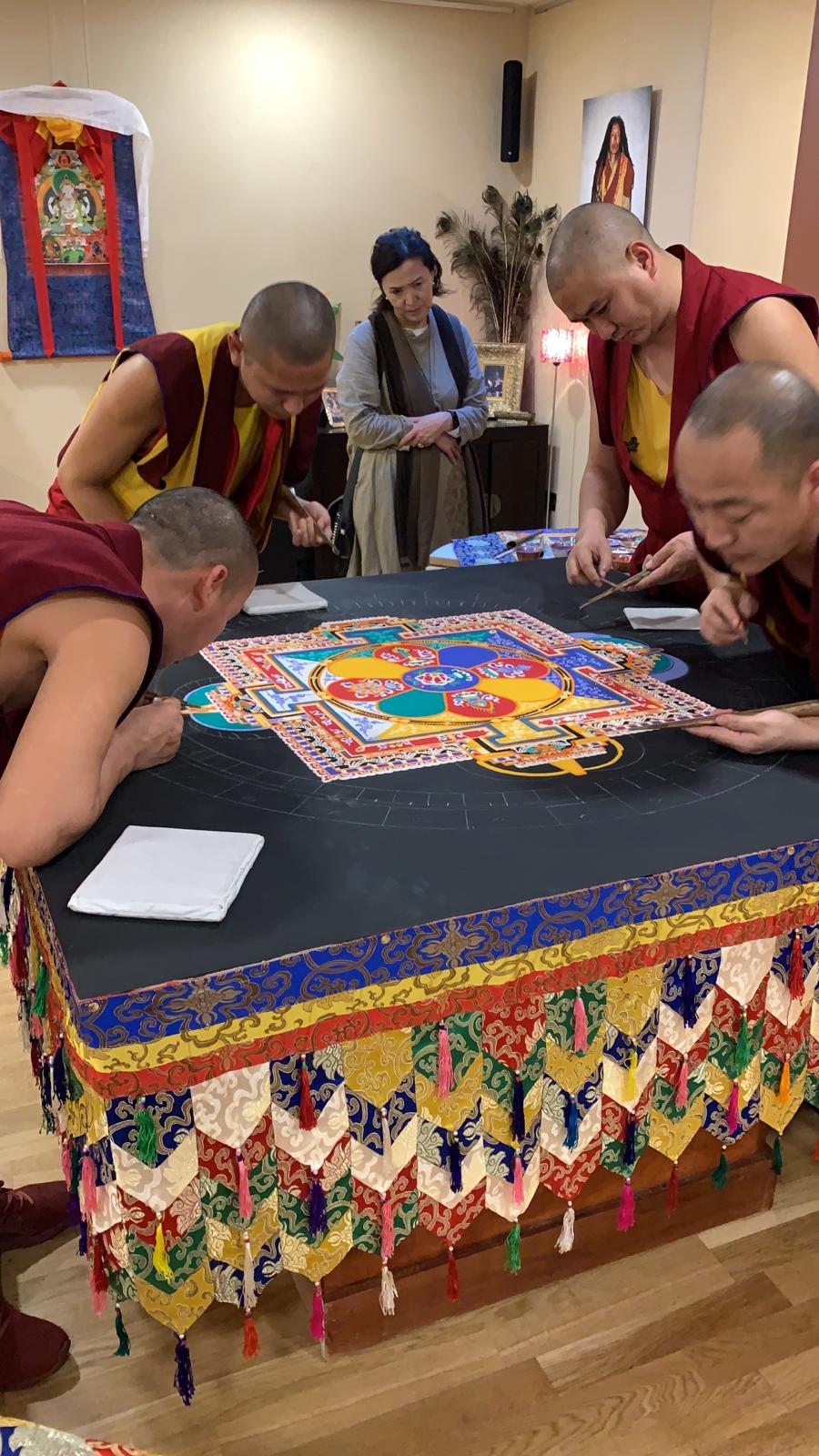

As the Gen-la , head of the monastery overseeing the work, explained, the creation of the mandala was both an offering as well as form of meditation, for the artists as well as the public witnessing. Mandalas, or cosmic maps, come in many forms with traditional Tibetan Buddhist arts. They can both be two-dimensional, such as sand mandalas or those found in thanka paintings, or three-dimensional such as architectural wooden sculptures. These help visualization during meditation and empowerments, aiding in the creation of mandalas in one’s mind. The complexity of each mandala depends on the teachings they are meant to convey; which deities and sacred texts. In the case of the one constructed at Lekdanling, the mandala was for meditation on world peace and compassion through Chenrezig, or Avalokiteshvara. Specific colors in the mandala were attributed to symbolize the five Buddhas, as well as particular elements such as earth, fire or water. Motifs such as the lotus flower were iconic objects associated with Avalokiteshvara. The bright colors of the dyed grains of sand were modifications of the older practice of making similar mandalas in Tibet, where colors were originally created from crushed rocks and semi-precious stones. The practice, taken to India, adapted its base materials due to expenses and unavailability. More modern pigments were used to beautifully dye grains of sand, and then carefully placed through metal funnels gently tapped and shaken to make shapes on a flat surface.

At Lekdanling, visitors were able to observe how the the placement of each detail and color of sand were guided by a template for the mandala, drawn and measured according to exact ratios of sacred geometry. The construction itself is a meditative process, approached with prayers. Images were constructed through practice and memory in careful precision as everyone marveled how the monks were able to build something without a visual guideline save a few lines for measurements.

On the final day, monks prayed and brought out special instruments as part of the chanting process, asking everyone present to also meditate on bringing benefit to all sentient beings. The dissolution also had a specific order, with grains being swept into the middle in an ordered manner. Here was the lesson in impermanence through many colors, each colored sand carefully placed, prayed and meditated over through a number of days to build a mandala of wonderful beauty, only to be swept up reminding us of the transient nature of all phenomenon. The colorful grains were swept carefully in a jar and brought over to nearby Victoria Park, a bright spectacle for the British public watching monks in billowing robes. Further prayers , chants and music were played through sacred Tibetan instruments as the grains were poured into the waters for adults, children, animals (yes animals!) and other beings in the park to reflect on. Each aspect of the mandala’s construction and dissolution touched many witnesses one way or another, whether through glimpses in real life, or live streamed and broadcast through the internet. We were blessed to be able to wonder on and witness ephemerality in such a beautiful way through an exercise of art, craft and heritage. We would like to thank the Drepung Kongpo Khangsten monks, Maureen Pugsley, Anne Bancroft, Jon Kwan and all other volunteers for making the event happen, a truly memorable way to round off all the events for the end of the year with Shang Shung Institute UK.