An excerpt transcribed from the Song of the Vajra Retreat, Hong Kong, 2012. May 18, day 3, part 2. Continued from issue 169 of The Mirror.

Rinpoche quotes from “The Treasury of the Supreme Vehicle” composed by Longchenpa.

།བཅིངས་མེད་རྣམ་པར་བཀྲོལ་མེད་པ།

bcing med rnam par bkrol med pa

We are not conditioned by ordinary dualistic vision and there is nothing to be liberated from. Everything is the relative condition in our mental concepts. These verses are related to the principle of Dzogchen Longde.

།ཁྱབ་གདལ་ཁང་བཟངས་ཡེ་ཡོད་ཉིད། །ཁྱབ་མཉམ་པ་ལས་རྣམ་འདས་པ། །ཡངས་སོ་ཆེའོ་ནམ་མཁའི་དབྱིངས། །ཆོས་ཆེན་འབར་བ་ཉི་ཟླའི་དཀྱིལ།

khyab gdal khang bzangs ye yod nyid| khyab mnyam pa las rnam ‘das pa| yangs so che’o nam mkha’i dbyings| chos chen ‘bar ba nyi zla’i dkyil|

These verses explain specific methods. In the Dzogchen teaching we have Dzogchen Yangti, Dzogchen Thögal, and so on, which have to do in particular with how experiences of the practice manifest, and when we understand how it is and have the capacity to integrate, we can also realize the rainbow body. The Dzogchen teaching develops with four kinds of visions called nangwa zhi (སྣང་བ་བཞི་ snang ba bzhi). The first vision is chönyi ngönsum (ཆོས་ཉིད་མངོན་སུམ་ chos nyid mngon sum). For instance, in the Dzogchen teaching when we have a vision of thigles it is considered to be a manifestation of our real potentiality. We have that knowledge and we see something concrete that represents our dharmatā, our real nature of mind, and this is the starting point of practices like Thögal and Yangti.

Then there are a series of practice methods called nyam nang gong phel. Nyam means experiences of the practices. In general we have different experiences. For instance, if we eat chocolate we can understand what “sweet” is. This is an ordinary experience and with it we discover all sweets.

When we do practice we can have the nyam, or experience, of the practice, and this is very important. If we are doing practice, of course we need to have experiences. If there is fire then for indicating fire there is also smoke. Smoke is not fire but indirectly we can understand that where there is smoke, there is fire. So a nyam of the practice is a manifestation of signs of the practice, which means that the practice is alive.

We can have different kinds of nyams. In an ordinary way there is nang nyam and sal nyam. Nang nyam means we can see something like an object with our eyes. If we experience manifestations related with the nature of elements when we are coordinating our energy or strengthening our elements, that means we have done the practice sufficiently and we have succeeded in realizing it. Of course we can also have visions of an aspect of the color of the element.

The nyam of vision not only means something we see with our eyes, it can also be something we hear or smell. Objects can manifest through all kinds of contact with our senses. Sometimes when we are very relaxed and doing practice in a dark retreat we might hear someone outside, or someone might be playing music such as the Song of the Vajra. In the real sense there is no one but we can hear something. That is an example of experience. If we are in the dark, we might smell a very pleasant perfume, like that of a nice flower with a strong smell. We can sense it concretely, not just in our imagination. These experiences are called nang nyam and are related to the contact our senses have with an object.

Another experience, called she nyam, is related to our mind. Sometimes when we are doing Shine practice, we may succeed in being in the state of Shine for a longer time. And even though we remain in that state for hours and hours we don’t feel uncomfortable. That is something like realizing the practice of Shine. And we may feel very happy or feel some sensation related to our clarity. Even if we are not thinking or judging something mysterious may manifest in our mind, for example something you wanted to understand. She nyam can manifest in different ways.

Then there is nyam nang. Nang means developing visions. For instance when we are doing practice like Thögal, with secondary causes we are gazing at sunrays and doing thigle visualization. Then many thigles may appear, and inside of these thigles Sambogakaya manifestations may also appear. Many different kinds develop one by one, increasing different kinds of visions like pure visions. This is called the state of nyam nang gong phel, a period of our practice in which visions appear everywhere without any effort. This is the second stage.

The third stage is called rigpa tsepheb. Rigpa is the state which we have discovered, not only the state of Guruyoga, or the state of contemplation. Tsepheb means maturing in the dimension of the state of rigpa. We are in this matured state of rigpa, kadag and lhundrub in which all self-perfected qualities are perfected, no longer needing to develop vision, seeing or hearing something. We are totally matured in the state of integration in which there is no subject or object. This is called the state of rigpa tsepheb.

Until this point we may have had many visions and think that our practice is developing. However, instead of developing it is now disappearing because it is integrated. In the Dzogchen teaching the most important thing is that we are able to integrate. Many people consider that it is very difficult to integrate everything in a perfect way because we are living in our dualistic vision. We know that everything is unreal, just as Buddha said: everything is like a dream. In a dream we can see, we can touch, we can do everything but we know that when we wake up, nothing concrete from that dream exists. When we have this knowledge even though we may not succeed in considering everything to be nondual, we are moving in the direction of integration so we should go ahead in that way and develop gradually. When we have developed and realized [our practice] then we can integrate everything.

For instance when we practice Namkha Arted – where namkha means space, our inner space and outer space – we gaze into outer space, into emptiness. At that moment we are not doing any visualization but are trying to be in instant presence. When we are in instant presence we have no consideration of outer and inner and it is easy to integrate with inner and outer space because space is a dimension, there is nothing concrete. In our dimension everything is concrete on a relative level, so it is not easy to integrate successfully. However, when we know our real nature and we are in our real nature, what we see is already governed by that knowledge. So we should integrate and develop that way. This stage is called rigpa tsepheb,the third stage.

When we succeed in that, it is called chösed: chö means dharma, sed means to consume, so it means all phenomena related with our mind [have been consumed]. We are no longer in mind. We are totally integrated in the state of the nature of the mind. When we are in that fourth stage, learning and studying methods of Dzogchen Thögal and Yangti, then we are in the last stage. Even if we do not succeed to do practice, we do not finish, we only just arrived to this fourth level, when we die we can manifest the rainbow body.

When beyond just arriving at this fourth level we also succeed in completing it in terms of explanation, method, everything, there is no death, just like in the history of Guru Padmasambhava and Vimalamitra, because our existence, our physical level, is already dissolved in our vision of the Thögal. It is totally integrated and gradually our physical body disappears for ordinary people. This is called jalü phowa chenpo, the great transference. This is the final realization, particularly in methods like Dzogchen Yangtiand Dzogchen Thögal.

When I am explaining, for example, the four Nangwa, you shouldn’t think that I am giving Thögal teaching. Some people might think that they received Thögal instruction. When I say you should integrate and you go and do something your own way and pretend to be doing Thögal practice, this is not Thögal, this is not Yangti. When you are seriously following then there are very precise instructions related to body, speech, mind, and how you develop step by step. These kinds of practices are very much related with experiences of vision and so on. Here it explains more or less this meaning.

།ཁྱབ་གདལ་ཁང་བཟངས་ཡེ་ཡོད་ཉིད།

khyab gdal khang bzangs ye yod nyid|

It means the perfected condition of all the qualities that we have.

ཡེ་ཡོད་ཉིད།

ye yod nyid|

This Tibetan term means that we have had this [perfected condition] since the beginning, not that we do practice to develop it.

།ཁྱབ་མཉམ་པ་ལས་རྣམ་འདས་པ།

khyab mnyam pa las rnam ‘das pa|

Khyab nyam means just being in that state is perfect, without changing or modifying anything. We just [need to] know how to continue in that state.

།ཡངས་སོ་ཆེའོ་ནམ་མཁའི་དབྱིངས།

yangs so che’o nam mkha’i dbyings

This perfected condition is everywhere and total, namkhai ying, just like the dimension of space.

།ཆོས་ཆེན་འབར་བ་ཉི་ཟླའི་དཀྱིལ།

chos chen ‘bar ba nyi zla’i dkyil|

This means that the nature of all phenomena is wisdom, luminosity, just like the light of the sun and moon. When we are singing SŪRYABHATARAIPASHANAPA this is the meaning.

Then we have the next verses.

།ལྷུན་གྱིས་གྲུབ་དང་མངོན་སུམ་པ། །རྡོ་རྗེ་རི་བོ་པདྨ་ཆེ། །ཉི་མ་སེང་གེ་ཡེ་ཤེས་གླུ། །སྒྲ་ཆེན་རོལ་མོ་མཚུངས་པ་མེད།

lhun gyis grub dang mngon sum pa| rdo rje ri bo padma che| nyi ma seng ge ye shes glu| sgra chen rol mo mtshungs pa med|

These are examples in order to understand the condition of the state of Dzogchen, although there is no example that corresponds totally. But there are many examples that describe it partially.

།རྡོ་རྗེ་རི་བོ་པདྨ་ཆེ། །ཉི་མ་སེང་གེ་ཡེ་ཤེས་གླུ།

rdo rje ri bo padma che| nyi ma seng ge ye shes glu|

རྡོ་རྗེ་ dorje, vajra: its real nature, its condition, is just like a (རི་བོ་ riwo) mountain, like a (པདྨ་ཆེ། padma che) lotus flower, meaning there is no defect, it is pure since the beginning. ཉི་མ་ nyima means like sunshine,སེང་གེ་ senge means lion, an example of the most powerful of all animals.

ཡེ་ཤེས་གླུ།

ye shes glu|

ཡེ་ཤེས་ yeshe means the quality and quantity of wisdom. གླུ་ lu means sound, different kinds of sounds that are melodic and that we consider to be important. Dance and sounds are always related to our different emotions, for instance, we are very happy when we are singing or dancing. We can also integrate in that state.

།སྒྲ་ཆེན་རོལ་མོ་མཚུངས་པ་མེད།

sgra chen rol mo mtshungs pa med|

Sound is the nature of all manifestations. Rolmo means that there is nothing perfectly similar to any kind of music or musical instrument. The tantras give examples of the primordial state explaining that it is like this or that.

།ནམ་མཁའི་མཐའ་ལ་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་པ། །སངས་རྒྱས་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀུན་མཉམ་ཞིང༌། །ཀུན་བཟངས་ཡངས་པ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་རྩེ། །མཁའ་དབྱིངས་བཟང་མོའི་དབྱིངས་རུམ་དུ། །ཀློང་གསལ་ལྷུན་གྲུབ་ཡེ་རྫོགས་ཆེ།

nam mkha’i mtha’ la longs spyod pa| sangs rgyas sangs rgyas kun mnyam zhing| kun bzang yangs pa chos kyi rtse| mkha’ dbyings bzang mo’i dbyings rum du| klong gsal lhun grub ye rdzogs che

In the Song of the Vajra we have these lines:

GHURAGHŪRĀSAGHAKHARṆALAM

NARANĀRĀITHAPAṬALAM

SIRṆASĪRṆĀBHESARASPALAM

BHUNDHABHŪNDHĀCHISHASAKELAM

They explain how we can find everything in the state of Dzogchen. If we are in the state of Dzogchen, we can integrate in any circumstance, in any condition, because they are [all] connected with the condition [of Dzogchen].

།ནམ་མཁའི་མཐའ་ལ་ལོངས་སྤྱོད་པ།

nam mkha’i mtha’ la longs spyod pa|

In the dimension of space there are infinite manifestations, yet even though there are infinite manifestations we can also infinitely integrate in that state.

།སངས་རྒྱས་སངས་རྒྱས་ཀུན་མཉམ་ཞིང༌།

sangs rgyas sangs rgyas kun mnyam zhing|

Although we may consider that now we are enlightened, or now we are in samsara, we are also beyond that.

།ཀུན་བཟང་ཡངས་པ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་རྩེ།

kun bzang yangs pa chos kyi rtse|

Being totally present in the infinite dimension of Samantabhadra is the highest state of existence we can attain.

།མཁའ་དབྱིངས་བཟང་མོའི་དབྱིངས་རུམ་དུ།

mkha’ dbyings bzang mo’i dbyings rum du|

The dimension of Samantabhadri means the dimension of emptiness. For example, the yum is manifesting as the dimension of emptiness. Samantabhadri is what manifests in that dimension. Then we have infinite considerations of all dharmas, of all phenomena, as well as of pure visions in a pure dimension. All are in this dimension [of Samantabhadri].

།ཀློང་གསལ་ལྷུན་གྲུབ་ཡེ་རྫོགས་ཆེ་ཧོ།

klong gsal lhun grub ye rdzogs che ho

In this dimension of the natural condition, the self-perfected condition, everything is perfected. This is the meaning of the Song of the Vajra.

But we should learn the Song of the Vajra in a different way, not only the words. We know that the Song of the Vajra is like a key to all the Dzogchen teachings. Then why do we have the three series in Dzogchen? First there is the Dzogchen Semde, where sem means mind. When we enter its real nature then we say semnyid, that is dharmatā, how the real nature of our mind is. When we say sem it corresponds to both [meanings].

From mind to nature of mind we are entering that state. This Dzogchen Semde series of teachings is related to the first statement of Garab Dorje: direct introduction. In order to have direct introduction we use many kinds of methods and experiences. Sometimes we do not receive that knowledge, particularly if we live very much with our mental concepts. When we listen to what the teacher says, we think “firstly he said this, secondly that,” and so on, constructing something in our mind. That may not work in a practical way and for that reason sometimes it is not easy for us to enter our real nature. The Dzogchen Semde practices work very well for discovering our real nature.

In Tibet, we have a lot of important teachers but they give teachings such as the Longchen Nyingthig series or Ati Zabdön of Minling Terchen. They always say that this is the very essence of the Dzogchen teaching. It is true that this is the essence but there are not many details for working with direct introduction, for example, connected with Dzogchen Upadesha. The Upadesha series is more connected with the last statement of Garab Dorje, once we have already discovered our real nature.

What is important? It is important that we integrate in the state we are in at any moment. This is an Upadeshamethod. Some people remain with their intellectual ideas. For instance, when I started to give Dzogchen teaching in Italy I started with an Upadeshateaching, a terma teaching of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpocalled Chetsün Nyingthig. People who followed this teaching thought how nice it was and that they had understood it. I gave this teaching for two years, not only in Italy but also in other places. Later I discovered that most people just had an idea, a kind of fantasy about it, and I wondered what I should do.

Then I thought that I should teach Dzogchen Semde because I knew that the three statements of Garab Dorje are related to the three series of Dzogchen teaching. However, it was complicated for me as I had received transmission, initiation and instructions in a more traditional way. Traditional doesn’t mean that we were given instructions, doing practices and gradually developing [our understanding]. So I studied instructions on Dzogchen Semde for a long time because I wanted to teach it to my students. I learned sufficiently and then later we started. We did two or three retreats and I became a bit of an expert of the Dzogchen Semde method and also discovered that my students were starting to have concrete knowledge of the Dzogchen teaching. This is an example of how important the Dzogchen Semde is.

After that we have the Dzogchen Longde, which is connected with the second statement of Garab Dorje, not remaining in doubt, using specific methods. You may recall that when we did the direct introduction we only used the experience of emptiness to discover our instant presence. However, we can also do that with the experiences of clarity and of sensation. In the Dzogchen Longde method, once we have received transmission there is a method in which we use all three of these experiences at the same moment. This state is called the state of yermed, which means that in that moment we no longer remain in doubt, we discover what really is the primordial state of rigpa and what is just an experience. The experience of emptiness and the experience of clarity are different. But when we are in instant presence, it is the same instant presence, we cannot say “this instant presence is related to emptiness” or “this instant presence is related to sensation.” When we have all these experiences together and discover that, this is called the Dzogchen Longde series.

Then we have the Dzogchen Upadesha, gradually integrating what we have learned. At the beginning when we are in the state of contemplation, when any kind of thought arises we do not go after it, we are not conditioned by it, and even though we notice that there is thought, we observe this thought, relax in that state and the thought disappears. Thought is self-liberated and we go ahead in this way. This is how we start. For example, there is what is called shardrol, which means that when thought arises we notice it, observe it, relax and it disappears. If we are not self-liberated immediately when we notice [a thought], we may need a little effort to observe it strongly, like fixation, in order to fully notice the arising of thought. When we relax then it disappears. This is called cherdrol [self-liberation through bare attention]. In rangdrol, when a thought arises we simply do not go after it and we are self-liberated.

When we start to practice Dzogchen day after day we do practice trying to continue in the state of Guruyoga in order to become more familiar with it. In the end we don’t need very much effort to be in that state.

Edited by L.Granger

Final editing Susan Schwarz

Tibetan & Wylie by Prof. Fabian Sanders

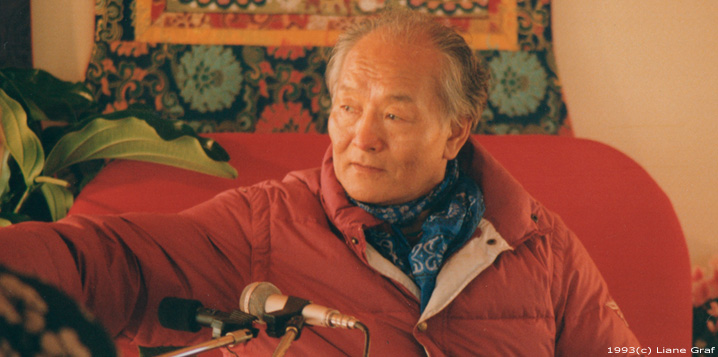

Photo of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu copyright Ralf Plüschke