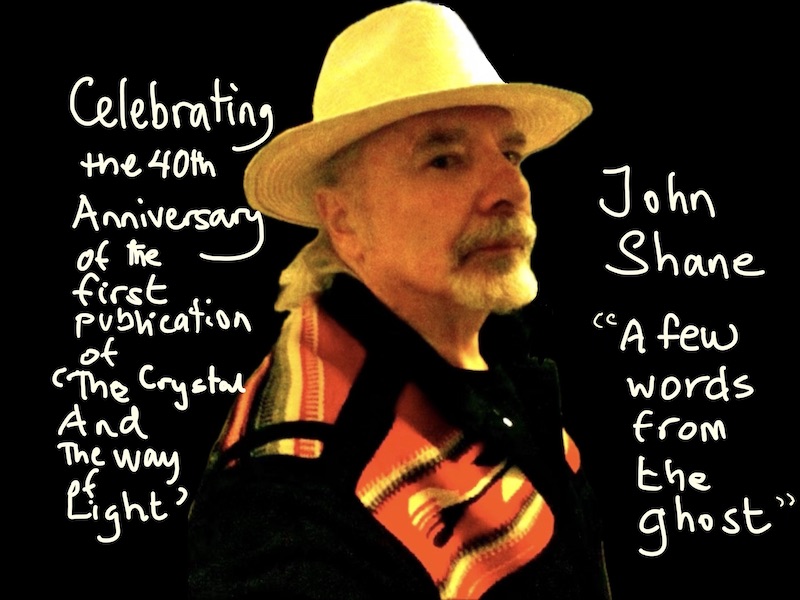

Celebrating The 40th Anniversary of The First Publication

of ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light’.

JOHN SHANE

Now that so many masters are teaching Dzogchen and so many books have been published on the subject, it might be difficult for many people to understand how radical Chögyal Namkhai Norbu was, not only in beginning to teach Dzogchen openly and widely to western students in the 1970s – which at that time, no other Tibetan lamas would do – but he was also very radical in agreeing to produce a book in English about the Dzogchen teachings intended for a wide general Western readership.

The fact that Rinpoche also decided to work on such a book with someone like me who is a poet rather than a specialist academic Tibetologist was also a very radical move, and the shape that the book took was very much affected by that decision.

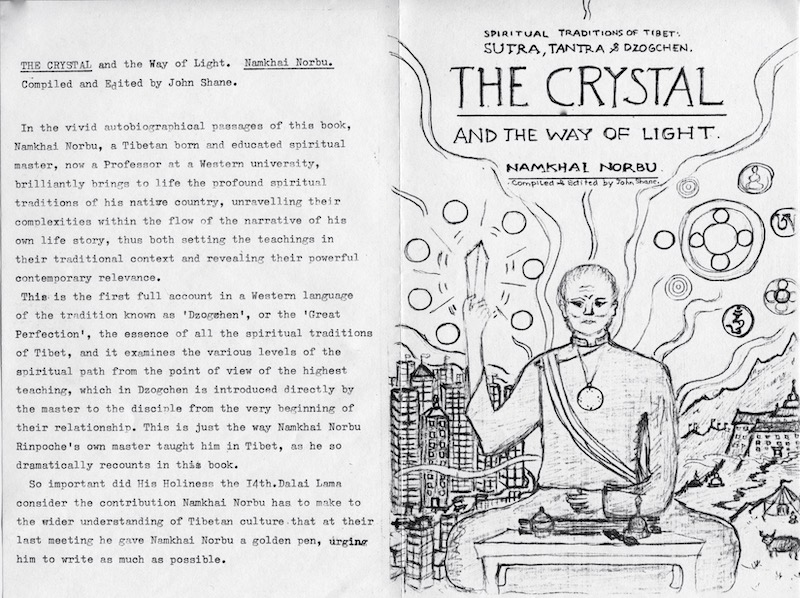

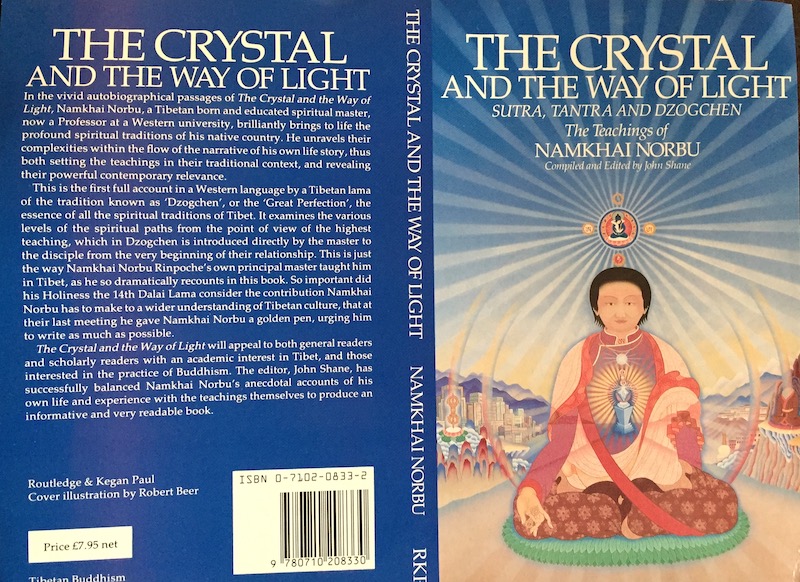

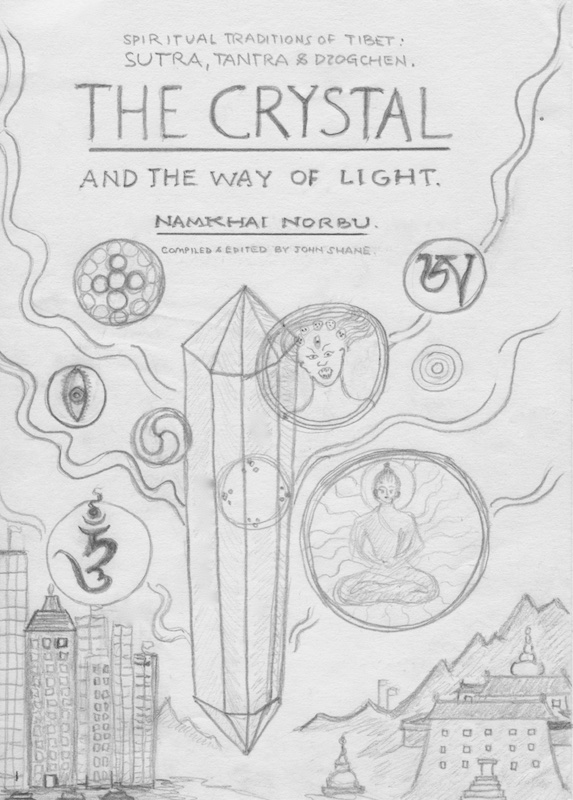

A sketch I made to give an idea of the illustration I wanted for the front cover of ‘The Crystal’, with also a draft of the rear cover blurb

In the process of producing the book that was to become ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light’, my role – in classical terms – would be described as having been Norbu Rinpoche’s ‘amanuensis’, which in the modern day terms of the publishing industry, means that I was his ‘ghost writer’.

When I first began work on the book in Italy at Norbu Rinpoche’s private family apartment in Formia, Italy, I had access to all the many tapes and transcripts of talks of teachings that Rinpoche had given around the world up to that date, and I began to read and listen to them, and all the stories and teachings that ended up in the book ‘The Crystal’ came either from those tapes and transcripts, or from what Rinpoche told me privately as we talked together while traveling around the world during the four years that, in the end, it took to produce the book.

One of the reasons that it took so long to finish the book, is that there was so much material in all those tapes and transcripts of Rinpoche’s talks that, as I began to work on the manuscript, it began to grew bigger and bigger as I tried to include in it everything that Rinpoche had taught.

This went on for some time before it became clear to me that what was most important to include in the book was what the reader needed to know of Rinpoche’s teachings, rather than there being included in the book everything that Rinpoche had taught, as I had at first wanted to do because I wanted to show how vast Rinpoche’s knowledge was.

Consequently, what had in the first phase developed into such a massive manuscript was gradually reduced more and more to reveal what was essential for the reader to gain a first understanding of Rinpoche’s Dzogchen teachings, which could be presented in a relatively short book, the main text of which could comfortably be read in one long sitting, with the photos and other illustrations with their captions and the graphic analysis providing further ways for the reader to get a full picture of what Rinpoche taught.

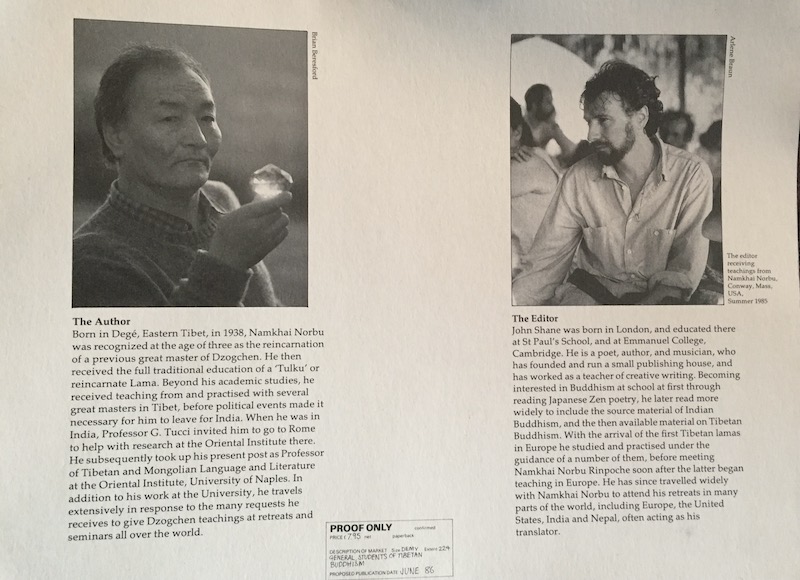

The cover of the first edition with Robert Beer’s cover illustration based on my sketched ideas

As I evolved this process, I showed Rinpoche a graphic structural analysis that I had set out on a large sheet of drawing paper – using skills that I had learned while studying architecture and fine arts at Cambridge University – in order to be able to show him an outline of the way in which I thought the material to be included in a book of his teachings should be organized, and Rinpoche approved the idea.

Given how often I had seen him hold up a crystal in his hand to give explanations of aspects of the Dzogchen teachings, I also told Rinpoche that I thought the book should be called ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light: Sutra, Tantra, and Dzogchen’, and he accepted my suggestion as a working title, which later came to be the actual title of the book when it was finally published.

As I read through the dozens of transcripts in various languages of Rinpoche’s talks and listened to the dozens of tapes of his teachings, I began to realize that, to create the text of the book, I would need to take pieces of what Rinpoche had said from one transcript and intercut that first piece with a piece from another transcript.

Of course, this was at a time when there was no internet or cellular phones, and, in fact, there were not yet even any personal computers with word-processing apps. Nor were there yet any centres of the Dzogchen Community at which I would be able to find people to help me with my work on the project.

Since there were no computers at that time, when I needed to cut and paste elements from one teaching transcript together with elements from another transcript, I had literally to slice up into pieces the pages of copies of the transcripts and then join them together in the new sequence using double-sided clear sellotape, and I then had to take the assembled pieces to the copy shop in the centre of the small town of Formia to be photocopied to make a new whole page for the manuscript.

Printers’ proof of the front and rear cover pages of the first edition of the book.

As I began to do this work of cutting and pasting pieces from different teachings together, I could see that I would also need to create entirely new paragraphs to join up pieces from different transcripts, and, there was a huge, ancient, battered, and very noisy grey IBM electric typewriter in the Namkhai family’s apartment where I was working with Rinpoche that he said I should use to type out these newly written paragraphs that would join pieces from the various transcripts.

I also had a Sony Professional Walkman and a small microphone that Rinpoche and I had agreed I would use to record what he said whenever I interviewed him to ask him questions.

When we first discussed the project of producing the book, I had assumed that when Rinpoche proposed to me that we would be ‘working together’ he meant that I would be working very closely with him on all aspects of the text at all times.

But then, after I had first arrived to work with Rinpoche at his family apartment a short distance from the beach in the seaside town of Formia, half way between Rome and Naples, where I would sleep on the sofa in the living room for six months, I sat with Rinpoche at his family’s dining table in the living room while Rinpoche was himself writing by hand in cursive Tibetan script with a black pen. I waited patiently in silence for Rinpoche to indicate to me that he was ready for me to speak to him so that we could begin to work together.

After a while, Rinpoche looked up at me from his work, and, seeing that I was not reading or writing but was instead watching him as he worked, he said sharply to me in Italian, ‘What are you waiting for?!!’ I meekly told him that I was waiting for him to work with me, which is what I had assumed we would be doing when he had asked me to collaborate with him on the project.

He replied, again in Italian: “You have mistaken the principle. When you come to work with me on a book like this, you do the work.’

So much for my expectations..!

I began to get on with the job of working on the book on my own while sitting across the table from Rinpoche.

But, in the next few days, I soon discovered that I had a problem, or, at least, I had what I thought was a problem. When I came to try to join two pieces of teaching taking excerpts from two different transcripts in two different languages, I didn’t mind translating the two pieces of what he had said in Italian into my written English. But when I had to join the two pieces from the two different transcripts there needed to be a new connecting paragraph, or sometimes even two or three connecting paragraphs, that had to be newly created, and very often these new paragraphs had to be written in the first person, to link both of the existing transcript paragraphs in which Rinpoche was speaking in the first person.

Another of the sketches I made to give an idea of the illustration I would like to see as the cover of the book

My problem was that – out of my great respect for Rinpoche – I was extremely uncomfortable with the idea of having to write in the first person as if what was written was by Rinpoche himself, but would, in fact, have been written by me.

Sitting at the Namkhai family dining table that day, I explained all this to Rinpoche, and I asked him to listen to me read the paragraphs from the transcripts in which he spoke in the first person and then to dictate to me the linking paragraphs that needed to be created in the first person to match the pieces from the different transcripts.

Rinpoche looked at me with a severe frown and said, ‘Do you know how to write?’

And when I said, ‘Yes, of course I do’, he then said, ‘Do you know what needs to be written?’

When I again said, ‘Yes’, this time he said quite wrathfully, ‘Don’t play the child with me..!! If you know how to write, and you know what needs to be written, what are you waiting for? Just get on with it and write it..!!’

From then on that’s how work went ahead in the coming weeks and months, with me continually checking back with Rinpoche on how things were going, while at the same time I also frequently checked in with the publisher’s editor in London, until – finally – years later, after many attempts at many different versions of the manuscript, a version of the book was finished that I was ready to submit to the publisher as the final version, and I brought the manuscript of that version to Rinpoche telling him that I would leave it with him so that he could read it.

I was confident that Rinpoche would be relieved, after we had been working on the book for such a long time, to see a final version of the book and would be happy to read it. But Rinpoche looked at me as if I was mad, and told me he didn’t need to read through the manuscript.

When I recovered from my surprise, I told him that I felt that I had taken on a huge responsibility in accepting to work in the way that I had, and that, while I was deeply grateful for the level of trust he was showing in me, there was no way that I would send the manuscript of the book to the publisher without him reading it.

Now it was Rinpoche’s turn to look surprised.

He thought for a minute or two. And then he said, ‘All right. You know that Walkman tape recorder that you’ve always used to record our conversations so that you could tape my answers to your questions about the teachings, about my life in Tibet, and about the book? Well, go away, read the whole manuscript into the tape machine, and then bring me the cassette tapes you’ve recorded, give me a copy of the manuscript, and as I’m traveling around the world to give talks and teach at retreats, with your headphones on, I’ll read the manuscript while I listen to your voice reading the text on the tapes.’

I gave Rinpoche a red marker pen that I’d been using, and said, ‘OK, but when you see something you want to have changed, or something you want to ask me about, please mark the manuscript with this pen so that I will know about anything that you have a problem with.’

As I’m sure you will be able to imagine it was a very strange experience indeed for me to sit – in the following weeks – in a quiet room all by myself and read aloud into a microphone – in my BBC standard English voice – page after page of my Tibetan teacher’s teachings, in the knowledge that he would in the coming months be listening closely to my voice reading back to him teachings that he had given to his students in his Tibetan language speaker’s version of Italian over the previous years.

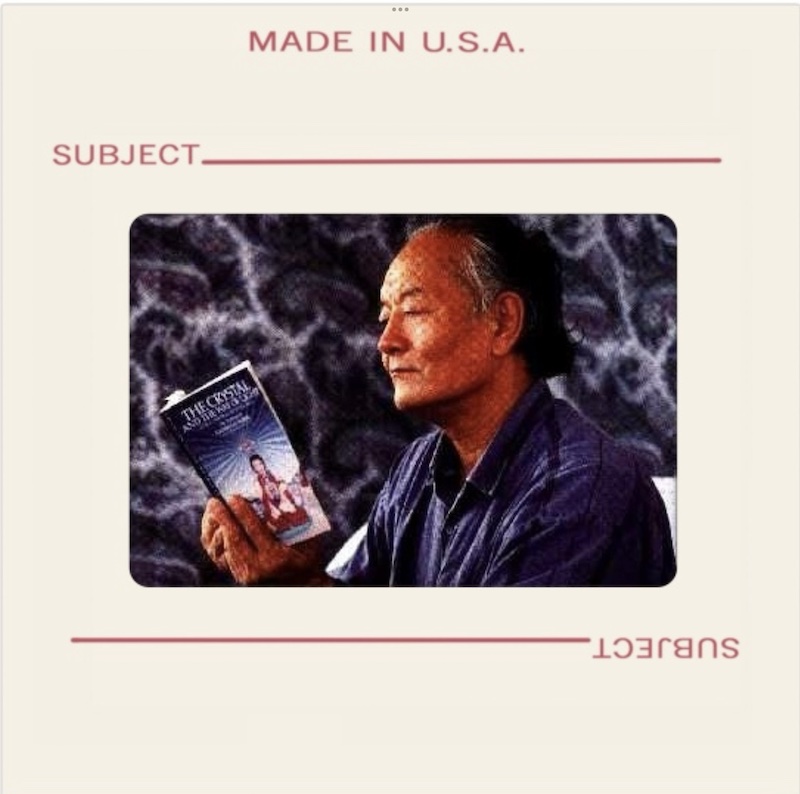

Norbu Rinpoche using a crystal rock to give an explanation of the Dzogchen teachings during a retreat in California, USA in the early 80s. (Photo by John Shane)

Some months later, when I was called to see Rinpoche and he told me that he finished listening to the tapes, I saw the manuscript on the dining table of his private apartment with the red pen lying on top of the closed folder. While I was waiting for Rinpoche to come into the room to see me, I moved the pen, opened the folder, and flipped through the manuscript. The pages all looked thoroughly thumbed, but there was not a single red mark on any of them. I put the manuscript back in the folder and put the red pen back on top of it.

When Rinpoche finally came into the room, I didn’t tell him I’d already looked at the manuscript. Instead, I simply asked him to tell me what changes he wanted me to make to it. He shook his head, and, with a smile, said he didn’t see the need for any changes. Then he handed me the folder containing the manuscript and said I should send it to the publisher.

After that, over many, many years Rinpoche never said anything at all to me about the book.

But not long after the book was published in its first English edition, when I went with Rinpoche to a Dzogchen retreat he gave at ‘Meditaticentrum Der Cosmos’, a large state sponsored meditation centre located on the banks of one of the famous canals in Amsterdam, I saw how pleased Rinpoche was when he noticed that – beside the sales counter of the Centre’s bookshop – there was a metal rack showcasing the store’s best-sellers – and ‘The Crystal’ was in the top place of the rack.

Seeing the book there in that top position in the rack, Rinpoche turned to me with a broad appreciative smile, and said, laughing: ‘Guarda..!! Siamo numero uno..!!’. ‘Look…!! We’re number one..!!’

Even though Rinpoche never said anything further to me personally about my work on the book, many years later I did hear what he thought of my work from my friend the late Nina Robinson, who was for many years the main secretary at the Dzogchen Community’s first centre, Merigar, that we had helped Rinpoche to found on the slopes of Monte Amiata in Tuscany, Italy.

Nina told me that, when she was taking care of some paperwork together with Rinpoche in the library at Merigar, a much-read and rather battered old copy of the first edition of ‘The Crystal’ was lying on the table at which they were working.

Pointing to the the book, Nina said innocently to Rinpoche, ‘John Shane did a good job on that book, ‘The Crystal’, didn’t he..?’ – to which, Nina later told me, Rinpoche replied emphatically, ‘A good job..?!! John didn’t just do a good job on that book…!! He did a fantastic job…!!’

Over the following years, I also had to take care of all business matters with publishers relating to contracts, editions, etc., as Rinpoche did not want to have to deal with all that on top of all his other many responsibilities.

In order that my word would carry weight when discussing issues with publishers – it was agreed that I should hold joint copyright of ‘The Crystal’ with Rinpoche, and that remains the case to this day.

But I never asked for any payment, and all the royalties that have resulted from the book’s sales have always gone to Rinpoche and his family, so my years of work on the book were my offering to Rinpoche.

————————

When I was first asked to work on the book of Norbu Rinpoche’s Dzogchen teachings, I was fully aware of the fact that the Dzogchen teachings cannot be received from a book alone: transmission of the teachings – and Direct Introduction – must be received from a fully qualified Master.

So, in devising a form for the book, I decided to design it so that one aspect of its content would make readers of the book feel that they were getting to know Rinpoche in such an intimate way that they would want to actually meet him in person. This was the particular function of the many stories of Rinpoche’s early life in Tibet that I included in the book.

As well as wanting readers to feel that they had come to know Rinpoche, I also wanted the book to be able to serve as a study-guide when they came to listen to Rinpoche’s teachings.

So what I concentrated on in the other aspect of the book was to go through the principle terms and concepts of the teachings – many of which involve untranslatable Tibetan or Sanskrit names and terms – presenting them to the reader in such a way that, when they did come to meet Rinpoche and received oral transmission of his teachings, they would already be familiar with those terms and concepts so that it would be easier for them to stay in the moment while listening to Rinpoche’s oral explanations without having to keep looking up the meaning of the unfamiliar Tibetan and Sanskrit terms that he was using.

Then – after they had listened to Rinpoche – I intended that newcomers would also be able to find, in the book, pages of graphic analysis of the teachings that would enable them to understand how the various component aspects of the crystalline structure of the teachings fit together.

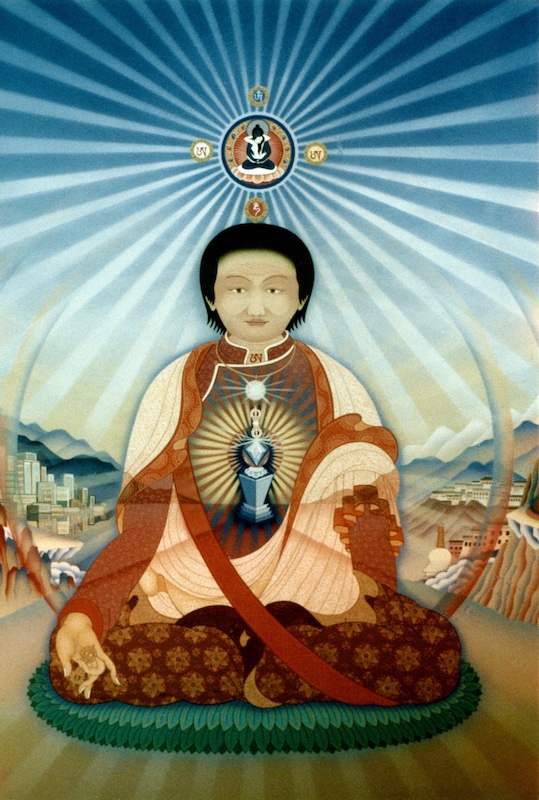

Norbu Rinpoche relaxes while teaching mudras to the thanka painter Robert Beer who made the cover illustration for the first edition of the book.

A further component of the book was the photos and illustrations, which were intended to help establish in the readers’ minds both the authenticity of Rinpoche himself as a teacher and the authenticity of the lineage of the teachings that Rinpoche embodied.

Once the book was published, it became a bestseller, and many people all over the world read it. This caused many students from many different countries to arrive who wanted to put into practice Norbu Rinpoche’s teachings, and, in that sense, the book’s success became one of the key early building blocks from which the Dzogchen Community grew.

Over the years, the original book’s continued availability and the many translations that were made of it into different languages helped the Community grow from a small group of people in a couple of countries to its current world-wide presence.

————————

The essence of one’s own mind is said in Dzogchen to be ‘inseparable from the mind of the guru’.

In the Guru Yoga of Dzogchen, one recalls this, and – if one has become distracted from the ‘natural state’, the state of Dzogchen – the state in which one’s thoughts and emotions and one’s physical manifestation spontaneously self-liberate – one links the essence of one’s own mind with the guru’s mind to return to the undistracted state.

Robert Beer’s painting for the cover of the first edition.

The process of producing this book in English of my Tibetan teacher’s teachings in a way that would make it seem that the teachings in the book had been born in perfect English spoken by him, required me to link my mind to the mind of my teacher and make myself completely transparent – ghostly, in fact – so that Rinpoche’s character, not mine, and the particular character of his teachings would shine through my English prose.

I already had experience of making myself ‘transparent’ in this way when I was translating for Rinpoche at his talks, and, in writing the book, I developed that capacity further.

If you haven’t yet read ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light’, it’s still in print with Shambhala Publications, and I hope that you will find time to take a look at it.

And if you have already read it many years ago, it might be time to re-read it in its 40th year.

In either case, the following two glowing comments from reviews by distinguished Tibetologists, Sam Van Schaik and Acharya Malcolm Smith, might perhaps encourage you to pick up the book:

Sam Van Schaik, a researcher at the British Library in London and author and editor of many books, including ‘Tibet: A History’; ‘Approaching the Great Perfection’ and many others wrote about the ‘The Crystal’s’ impact on him when it was first published:

‘…It was not until the eighties that Dzogchen began to be widely known. This was largely through the teaching activities and writings of Namkhai Norbu, a Tibetan lama who had been invited to Italy in the sixties. Working at first as a professor at Naples University, in the seventies Namkhai Norbu gradually began teaching dharma students, focusing on the presentation of Dzogchen.

Then, in 1986, came the publication of Namkhai Norbu’s ‘The Crystal and the Way of Light’, which brought the teachings of Dzogchen to a far wider audience in the English-speaking world.

The book was an engaging mix of autobiography, anecdote, and Dzogchen teachings. It was the first place I encountered Dzogchen, and I was fascinated…”

Acharya Malcolm Smith, translator and editor of several books from Tibetan, including ‘Buddhahood in This Life: The Great Commentary by Vimalamitra’ wrote about the first publication of ‘The Crystal’:

“The Crystal And The Way Of Light was the book that broke the ice of the Dzogchen teachings in the Western World.

Prior to the publication of this book, there were no accessible, easy to understand, writings about Dzogchen for the general reader. Even though this book is accessible, its contents are nonetheless profound and lay out the context of the Dzogchen teachings in a clear manner…”

————————

When Norbu Rinpoche and I began work together, he said to me: ‘You have mistaken the principle. When you come to work with me on a book like this, you do the work’.

And that is exactly what happened in the creation of ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light’.

But, despite the fact that it was me that did the work of the writing of the book, it seems that I succeeded sufficiently in making myself invisible in the book to the extent that most readers have assumed that the book was entirely written by Rinpoche himself. And I have always been very happy about that.

Following the 4 years of hard work that it took to complete the manuscript of the book, Norbu Rinpoche, was finally able to hold a copy of the book in his hands.

But now that ‘The Crystal’ has successfully been in print in its English language form for 40 years, and has also been translated into many other languages, as we arrive at the eighth year after Rinpoche himself passed away, and as I am myself now in my 80th year, I felt it might be time for ‘the ghost’ who collaborated so successfully with Norbu Rinpoche to come out of the shadows for a brief moment to write a few words intended to shed light on his work on the book before ‘the ghost’ finally fully disappears, fading from this Earthly dimension.

So, as I write these words to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the book that came into existence as a result of my having, in a very practical sense, offered ‘body, voice, and mind’ in Rinpoche’s service, I also want to celebrate all the other wonderful things that have come to fruition in the Dzogchen Community in the same 40 years as a result of the individual and collective offerings of so many of my fellow students.

And, at the same time, I look forward in the hope and expectation of the further great things that will come into the world as result of what future generations of students of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s teachings, and future readers of ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light’, will have to offer.

Sarva Mangalam – May It Be Auspicious…!!

—————————————

If you would like to write to me, please do so though my Substack publication, where you can also read and listen to more of my work:

https://johnshanewayofthepoet.substack.com.

All photos and images copyright John Shane