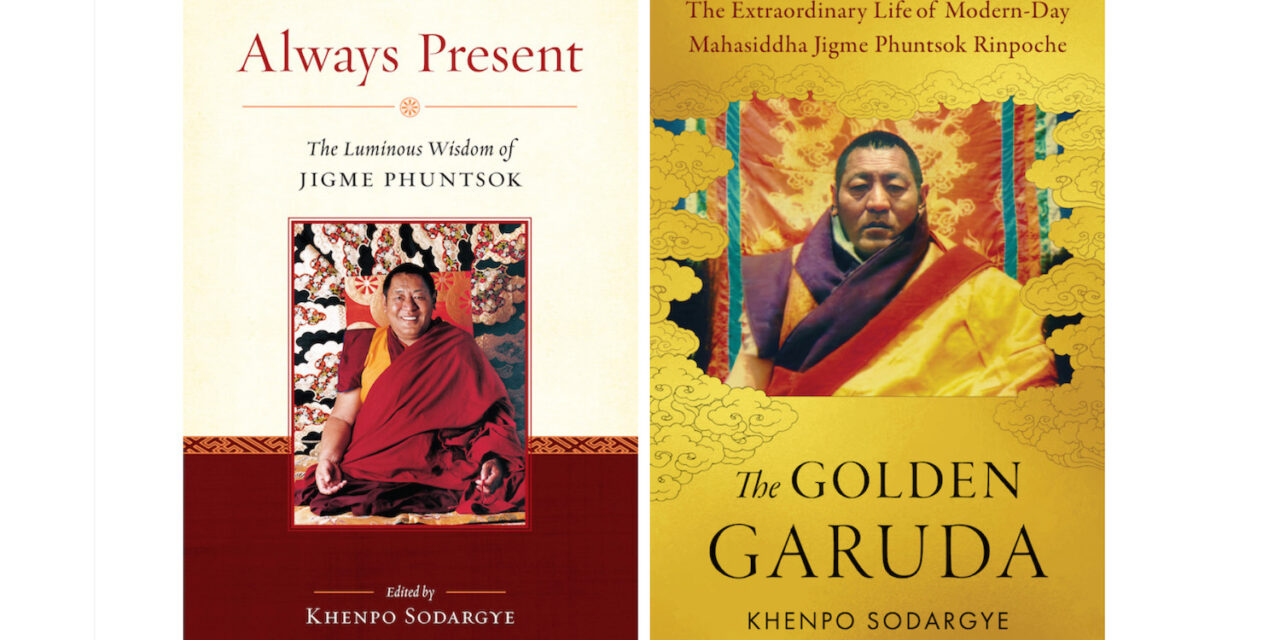

The Extraordinary Life of Modern Day Mahasiddha Jigme Phuntsok Rinpoche

By Khenpo Sodargye,

Shambhala Publications 2025,

pp. 245, ISBN 9781645473190

Always Present – The Luminous Wisdom of Jigme Phuntsok

Edited by Khenpo Sodargye,

Shambhala Publication 2015,

pp. 130, ISBN 9781559394505

Review by Alexander Studholme

The lives of many of the great lamas who followed the Dalai Lama into exile in 1959 are well documented. Much less is known about those who stayed behind in Chinese-occupied Tibet: information has tended to come in fragments and has often been desperately sad. Within this context, then, The Golden Garuda, the biography of Khenpo Jigme Phuntsog (1933 – 2004) stands out. It is a monument to spiritual success, a detailed account of an amazing Buddhist master who, despite the hardships of his time and place, was able to achieve incredible things. At their meeting in Dharamsala in 1990, the Dalai Lama called him simply, “the protector of the Dharma in the Land of Snows”.

Khenpo Jigme was most famous for establishing Larung Gar, a religious encampment set in a remote valley in Eastern Tibet, which by the 1990s had grown into literally the largest Buddhist institution in the world, home to thousands of practitioners and the training ground of a new generation of Buddhist teachers. Exactly how this was possible goes largely unexplained: this is essentially a pious hagiography, written by a close disciple, into which politics rarely intrude. There are early chapters on the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, from which Khenpo Jigme – continuing to wear his monastic robe, albeit under his outerwear – emerges miraculously unscathed. But thereafter the Chinese authorities are noticeable only by their absence.

He was truly a renaissance man, a man of many different aspects and parts. In the early photos – thick set, with strong features and swathed in sheepskin-lined robes – Khenpo Jigme looks more like a heavyweight boxer than a spiritual teacher. Later, he can look gentle, almost motherly. An accomplished scholar of the early Indian texts, he could defeat Gelugpa geshes in debate, whilst he was also, we read, one of the few lamas left in Tibet who could authentically teach Dzogchen. He was a prolific terton: the pages of the biography are replete with descriptions of the wondrous discovery of stones, statues and treasure chests. Sariras, supernatural pearls, “often fell from the sky” during his teachings.

Within a rich visionary life, he identified as the son of a minister of King Gesar, the mythical Tibetan Dharma warrior. One of the most colourful passages of the book recounts a dream in which he enters the court of King Gesar – “a palace built of precious jewels” – where he meets a lovely Khampa girl, who sings him a beautiful vajra song. Another chapter describes how he gathers a large crowd to open a “terma gateway” through which the faithful may enter directly into a pure realm. Moreover, he hopes to enable “scientific researchers to witness this substantial Buddhist mystery with their own eyes.” When he is unable to achieve this extraordinary ambition, he weeps.

Certain recurring themes emerge: numerous encounters with Guru Padmasambhava and Mipham, one of the central figures of the non-sectarian rimed movement of early 20th century Tibet; devotion to Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, and to Yamantaka, Manjushri’s wrathful form; an emphasis on the Mahayana aspiration prayer of Samantabhadra and, finally, on the Vajrayana practice of Vajrakilaya, the yidam deity of Terton Lerab Lingpa, the lama said to be Khenpo Jigme’s previous incarnation

Strikingly, throughout all this mahasiddha-type activity, Khenpo Jigme remained a monk. He ordained at fourteen and was enthroned as a qualified lama at the age of twenty-four. At this crucial juncture, he might have returned to householder life. A woman appeared – “breathtakingly beautiful” – who announced that she was a dakini with strong karmic connections to him and that, by taking her as his consort, he would greatly enhance his spiritual powers. To the dismay of some of his lama colleagues, who argued that a consort was indeed beneficial for the life of a terton, Khenpo Jigme turned her down. He insisted that it was more important for him to uphold the image of a pure monk in an era, as he put it, when too many mediocre individuals “conduct their so-called consort yoga for their self-serving desire and lust.”

This stress on maintaining the purity of the sangha did not make Khenpo Jigme any more popular. In 1985, in a sign of his authority, he circulated an open letter to monasteries throughout Eastern Tibet, stating that all monks should maintain their vows in a pure way. “After the rectification,” he publicly remarked, “many people hated me to the bone and slandered me for no reason… [but] if no intervention had been introduced, Buddhism would have been doomed if left as it was.” His thoughts on this issue are also to be found in Always Present, a short volume of his teachings. There, he warns at some length of the dangers of deluded, corrupt and avaricious monks and of fake tulkus, adding modestly that he never once thought himself to be the true reincarnation of Lerab Lingpa.

Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok did not merely revive, maintain and police Buddhist tradition, he was also creative and forward thinking. He introduced nuns to his community in unprecedented numbers for Eastern Tibet, awarding a select few the highest degree of khenmo, thus allowing them to be teachers in their own right. And perhaps most significantly, in 1986 he began to encourage Chinese men and women to come to Larung Gar to practice the Dharma.

In order to connect with a Chinese audience, Khenpo Jigme led several parties of thousands of devotees to some of the major Chinese sites of Buddhist pilgrimage, such as Mount Emei and Mount Wutei, where he commissioned many statues of Guru Padmasambhava. Then, towards the end of his life, Khenpo Jigme earnestly propagated the practice of reciting the name of the Buddha Amitabha whilst cultivating the intention to be reborn in his Pure Land: a form of Mahayana Buddhism that, while an established element of the Tibetan system, is also, of course, very popular in China.