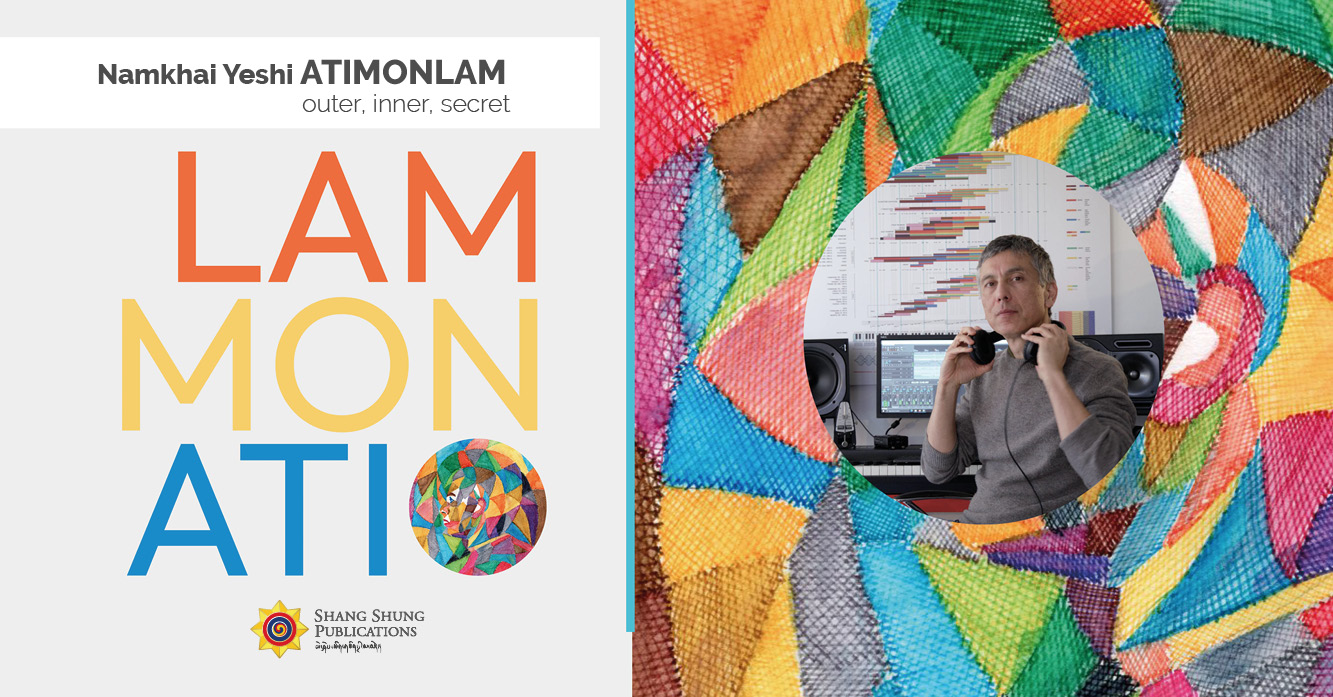

The Mirror: Dear Yeshi, you have recently created a sound composition called ATIMONLAM, which is described as a guided meditation to discover our inner nature. Can you kindly tell us how this idea appeared and about the history of the creation of this work?

Namkhai Yeshi: The history is very long. It’s not a history like you may think, it’s not a common artistic work in which you have some kind of inspiration with which you start working and setting up your artistic work. It’s very long because I’ve been thinking about the possibility of using sound.

In the teaching of Dzogchen we have two main methods. The first one is form, the second is sound, which relates to the simple fact that we are mostly working in a union of emptiness and clarity. Normally emptiness is represented by form as the essence of the mind is emptiness. And clarity is generally represented as energy and energy for human beings is mostly sound. As a matter of fact, we usually speak about our voice as an expression of energy. So the idea was simply to fill a gap that we have in which we have very good material to work in the field of form and we don’t have very much to work in the field of sound.

We have many examples of sounds. The simplest example from Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s teaching is purification. We use sounds related to the elements, we have mantras, and we also imagine specific colors. We combine all these aspects of form and sound in a unique way. And this is not very common. It was presented by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu as a specific method. Now everyone is doing purification in the same way, but actually this is a specific method. It’s not really the most common way to do it. So it was his choice to use sound in that way, just like the main practice we do is the Song of the Vajra.

The Song of the Vajra is a structure based on sound and it is also not the most common activity or practice or kind of meditation you would do. It’s presented as part of the series of Semdzin. We can also discuss this aspect, but it’s not really the important thing. The important thing is that in the Song of the Vajra we have all the structures and information that are related to the full series of the Dzogchen teachings, at least those that have been transmitted and given by Chögyal Namkhai Norbu dating back to the full lineage. It’s actually all contained in the same song, at the same moment you are singing it. And this is the main idea – that we are entering directly into the nondual state through the sound. Even if it’s a single sound like “A” or the full Song of the Vajra, no matter how you do it, the key point is that you are entering through sound. You are not entering through form, you are not using a conceptual idea.

Let’s say, for example, you gradually enter a calm state, like in all explanations of nepa, gyuwa and so on. You move from that conceptual understanding of your own mind and enter by the knowledge of your mind which is more conceptual. Then you discover movement and go straight into the nondual state. Instead here, the nondual state is directly introduced by ourselves through the sound, not by someone else externally. And the sound happens in time. Being a non-synchronous event, sound helps us to enter directly into the present state.

I’ve been working and thinking a lot on how to fill this gap, how to create something that may allow anyone, with or without any experience of the Dzogchen teaching, to have that kind of experience. At least to perceive something that at the very first moment could be sort of a general experience of the present time. Just like when we say that the ordinary mind is the gate to the nature of mind. Then from this ordinary understanding of presence you can enter into the real understanding of awareness and knowledge of present time and actually discover that this presence and this present time are your own natural state. This is how you may enter directly through the sound into the understanding, into your own natural state beyond any kind of such mental activity like judgement.

My idea was to use a common form, a common way to present this, which is modern music. After the Second World War till recent times there has been a growing knowledge and development of the repertoire of modern music, which has something to do with present time, mind and so on. It’s not like the classical music from the late 19th century, like post-romantic Russian music, just to quote the most classical music we listen to. Every movie you watch, there is epic music – this is Russian music, there is no discussion about this. This comes from Rimsky Korsakov’s structure of orchestration, and from that time till today, we still listen to the same music.

After the beginning of the 20th century, we had a development of completely different kinds of music, non-tonal and so on, and also of electronic music, which somehow has some common elements with meditation, mental practices, and knowledge of oneself, because in the 21st century things have changed a lot. By using this more common language, anyone can access that state.

The idea was to give that kind of experience to everyone. And for those who have very good knowledge of that state it’s a way to improve in a very well-defined path. It is not just, ‘Oh, now I’m going to stay present and not get distracted.’ Instead, it’s a guided way to do it.

M: ATIMONLAM is in three parts which are described as outer, inner, secret. What does each part convey to the listener?

NY: There are three moments, or three movements like in music, but mostly it’s three stages. There is an external stage in which there is still the world of outer sounds, sounds coming from the real world you may still somehow refer to; the musical gesture can still refer to something that exists. Then there is a central part, which is completely the inner world in which you start to hear sounds that come from a physical body: you focus on breathing, on the heartbeat, on sounds that are not normally heard with the ear. And then there is a secret part, or let’s call it a part which is more absolute or conceptual, which is the sound itself.

What really happens in the mind? You go from an outer sound to an inner sound, to a sound that exists by itself, that doesn’t need to be an expression of energy. That was the main inspiration – the idea of how do I turn this understanding, this knowledge I have, that kind of experience, into something that you can hear, that you can experience. I thought, let’s use a sound that is not practically possible to fix on a support. I chose a sound that is not in any way possible to represent digitally, which is the sound of a flame, because a flame by itself is a concept.

How do we suggest the idea of fire burning? Obviously, fire is a special element. In the teaching fire has a very important meaning. Fire burns everything, but nothing burns fire itself. This is the reason why it’s an important example. We have several types of mental exercises, like in the series of Rushen, which are essential for the practice of Dzogchen Longde, where we experience fire. We experience working with clarity in the field of imagining fire and working with that unstable element. So I thought, let’s try to use that sound that you practically imagine, by giving an external gesture, the gesture of lighting a match.

But this is going to happen many times, so it also becomes the musical pulse. It’s like the beat of a song. That is the pace of the piece that allows you to come back each time to that kind of presence, because the sound is very strong. It’s obviously stronger than in any possible reality, because it’s been recorded very near the place where the matches are lit, and it lasts exactly the time of the flame. It’s not been modified or transformed in order to have it for a longer time. It’s exactly that time, because this is the final goal.

My idea was to put that element that repeats and people can get into that present state exactly in the natural time it’s really needed, which is about maximum two seconds. Two seconds are enough to enter directly into a nondual state. It’s like when you’re singing “A” and “A” lasts a few seconds. In about one or two seconds you enter that state, you are relaxed and present, and you have awareness of all you have learned about this teaching.

And the idea was, let’s repeat this many times and have a structure that is basically three times the Song of the Vajra. The Song of the Vajra lasts a little more that seven minutes. I multiplied by three, created the three movements, and added this repetition related with the flame to all these parts. Everything comes out from the flame. That was the idea.

The inspiration was how the flame burns. There is an initial part in the sound that is like turbulence, like a wind. It’s a non-real sound, a noise that comes from silence. And then slowly, slowly it moves the air and creates some sound that is present only in the environment. It’s not a real sound that has some particular components, but a very strong turbulence of the air. By having that mental movement, you imagine, recall that experience of heat, of light and so on. And everything in that musical piece also refers to all these aspects.

As you have the flame, you also have the heartbeat which is something warm. Also when you’re breathing, it’s an idea that you’re exchanging air, you are being refreshed, but at the same time you are transforming, producing internal energy. You need that oxygen in order to burn anything in your body, to transform any food, any elements from a cellular point of view. Also internal breathing is not a breathing we normally think about. When we say ‘breathing’, we have the external breathing, inhaling and exhaling but we also have cellular breathing, which is more similar to a plant, to a vegetable. It’s not really something that is related to a movement of inhaling and exhaling. It’s more a chemical reaction like photosynthesis. This is mostly how cells breathe internally, and this is also the reason why from that part, that movement, we move to the third part, which is the secret part more related to knowledge.

It’s like simply saying that you know that it works this way. This is why many elements from the outer world disappear in that section, and for the first time harmony appears. In the previous part, there is almost no harmony at all; there are very few notes, common pitches of music. Only in the final part, we start to have harmonic structures which are very dense and have a lot of variation. Everything is obviously built on my tonality, which is c-sharp because I sing, breathe and think in c-sharp. These harmonic structures are a large development of c-sharp.

Normally we have b-flat – Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s main tonality is b or b-flat, it depends – c-sharp and d for more spiritual music. All Masses are usually written in d because d was considered, at least in the classical period, to be the correct tonality for a Mass, for religious music and so on. C-sharp is not really used in the western world, but in the eastern world, mostly related with Indian music which has a tonality centered around c-sharp. For this reason, I thought this should be fine.

Then this idea had to be translated into something that you can actually hear, you can work with. I’ve been testing these sounds in order to see if they promote some kind of interesting stage or mental state. To do that, I obviously had to stop working for some days and listen to what I had done, without any intention, and then understand how it really felt, if it worked or not. Obviously it had to affect my perception. If it affected and worked, then I went in that direction, otherwise, I reworked some parts but the main idea was quite correct from the beginning.

From a production point of view, I had to collect all the sounds. Most of the sounds are coherent and recorded in Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s house. Practically everything that you hear in that composition comes from there. All sounds, also external sounds, come from Merigar. There’s nothing that has been added on purpose to enhance or have some aesthetic final effect. The full work has nothing to do with aesthetics, it has a functional goal. I was working with the idea of creating a functional work, a musical work, so that it promotes that kind of state without thinking or feeling the need to have an aesthetical purpose.

Whether you like or don’t like the sounds, it’s not the main point. The main point is if you step into some kind of interesting mental state, which means the work has reached its goal. If instead you are somehow captured by the aesthetic work, then you practically failed because it’s very easy for any musical piece to be aesthetic – you follow harmony, rhythm, you add certain specific elements, and then it’s aesthetically beautiful. But this doesn’t relate to having reached any kind of goal in terms of meditation.

M: We know that you used objects belonging to your father, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. Which objects did you choose and what inspired you to choose them?

NY: The objects obviously cannot be any objects. In order to fix this sound in a support, such as a digital recording, you need an object to produce some sound. You need to work with those objects. Normally when we refer to objects, at least from a musical or traditional point of view, we speak about “found objects”. In French we say objet trouvé. Found objects are typical objects that produce sound that you find interesting and you are mostly captured by the sound itself. It’s a spectro morphological characteristic rather than the object itself. You’re not interested in the fact that the object has a specific function in the real world, but in the fact that that object produces an interesting sound that refers to the final result or the aim of your artistic work.

This was a tradition starting from the 1960s called musique concrète or concrete music and it refers to the studies and research of the 60s in music in France, mostly in Paris, by a group whose leader was Pierre Schaeffer. That kind of music, that is still very popular today, is based on the idea that you analytically listen to those sounds in terms of what characteristics they have for the fact that they are sound and nothing more than that.

You usually classify them using tables in which you name this sound, you say this sound has this characteristic and it’s useful to do this and that and put it in your library. Then you go through all the objects that are available, you listen to those objects, and most of all you listen to those objects in the proper room. Maybe an object works well in one room but doesn’t work in another.

Some of the objects were recorded in the small gönpa that is on the upper floor where my father would usually fill and authenticate statues. There is his hammer and all the tools to fill the statues. There are many different parts of the room which are made of wood, mostly the ceiling. It’s a wooden painted ceiling with mantras made by Migmar and there is also some glass, some tapestries, carpets, and so on. These materials all together create a specific kind of sound environment and I recorded many objects there on purpose taking them from his studio and bringing them up in this small gönpa because they sounded better there and also it appeared to be more coherent.

I used some musical objects like flutes and some other strange sounding objects that had been gifted, like so called Tibetan bowls. I don’t like that sound but I created some interesting emissions by scratching them or doing some strange things.

The most important part in this composition is the shift from each movement going from one stage, mental state, into another which usually happens suddenly. The most important one is before the third part because it represents tregchod, the idea of cutting through with a single very high pitched sound. It’s Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s bell for initiation that I recorded in different ways. I combined that sound in reverse so that instead of sounding like “dong”, it suddenly goes very high and cuts that sound. I also added something very strange, which is in his room today. There are plastic dust sheets that sound very strongly, similar to water, to the noise of the waves on a large surface of water, like at the seaside. I mixed this sound and that created this very strong impact in which you come back to the present state.

The tension is an expanded tension because the third section is extremely dense. There is a lot of energy going on, but there is no real tension. It’s energy that is not moving and the only movement is created by harmony. You have outer movement at the beginning because things are moving: there are birds, there are people walking, there are things happening externally. Then there is a central part in which only the physical body is moving: I’m standing still with the contact microphones on my chest and everything is moving because my body is moving. I’m breathing, my heart is beating, I’m in a very relaxed state but the body is very active. Then, suddenly, you have this sound of tregchod which cuts and you go into a stage in which there is a movement that creates this expanded, very dense structure in which there is movement of appearing and disappearing harmonic things. There is a very large harmonic progression, c-sharp, like a full orchestra, from very low to very high pitch, and in the movement there’s just this large expansion and that’s all.

But before that there is this very strong sound. And what is interesting, if you analyze the sound of that bell, is that it practically contains many of the sounds that you will hear in an expanded version later because I have related it from a frequency point of view so that it sounds like an expansion of the same thing. That bell is a huge bell for initiation that is still there although that room now is not used. There are these plastic covers, there are different things and some of them are exactly as they were left.

So when I’m suggesting the idea that now we are in the present time, the objects are not in the small gönpa, but where they are. The difference in place, in sound space, is when you hear it large and then you hear it like a sound that comes from a place that seems to be ordinary. In the real sense it’s the present time. It’s how the room is empty now compared to the sound of the objects with their meaning, with their discovered or found function.

This is a contrast that I wanted to present so that when you are listening, you hear that the sound space is changing like layers. You change focus, like when you are looking at something with your eyes, you move your eyes focusing on different parts of a picture, and your time changes while you are looking at this particular part of the picture. In the same way you are changing time given by this illusion of the sound space because we are in the present time now compared to the object as it was always used in that smaller, more intimate environment, the small gönpa.

I created these two different environments in the composition very clearly so that you can have that kind of experience. And you may experience something like sounds that come from your childhood compared to the sounds of when you are an adult or older. I tried to be very coherent in this so that when you hear all these sounds, they are also recognized for their own environment and you can actually relate to that because, when they are listening, people create their own idea, their own virtual world with these sounds. What was important for me was that this world is consistent so that you can find that it is a familiar world that becomes more and more familiar the more you listen to that work.

And then at the end you can understand how a certain experience is also related to proximity to the teacher. By understanding that, probably you also understand how you relate to the teaching. By using objects, that’s the difference. Those objects have this kind of power to bring with them this kind of experience.

M: At the moment you are completing your training in electronic music at the Conservatory of Music in Florence and compose music on the computer. Are there any reasons that you chose this particular field of study?

NY: As I said, I thought sound is a gap to fill because some years have already passed and honestly I did not see much evolution, at least in the aspect of the Dzogchen Community, teaching and so on. Maybe I don’t know enough about what’s going on, but the point is that I did not see anything that was really a revelation of something that is working. As I am growing older, I thought that it’s time to do something and I would like to do it with music although I can’t say that I had a very clear idea.

Initially I thought only to do something I like as I never had the time before. Many people think that I spend my life doing my own things, but this is not true. I’ve always supported my father all my life. So I thought, now maybe I can have some free time as there are people who are taking care of the Community, who are teaching and so on, and maybe for the first time in my life I can dedicate some time for myself and do something interesting.

My initial idea was to study music in the most common understanding of this term. The kind of music you do live, something that happens, not something that you fix or create on purpose in the studio.

Then I decided to attend electronic music school and I discovered by chance that there was one of the best historical schools in Europe in Florence. I found that there is an interesting tradition right here in Florence and I met the person who was coordinating the composition class and started to study with this idea. Then I realized that there is a lot in common, a lot that I can actually apply to make a twist in the way we conceive of the teaching itself.

Since childhood I have been raised with the idea that every ten years maximum you have to do a ngondro. I have done it already three times in my life and every time it is longer. I thought now I’ll do it for five years. It took me three years because when I spoke to the coordinator he told me that it’s very difficult to do if you don’t have any experience in general, in terms of training the mind, training the ear.

I thought from the very beginning I was ready to spend at least three or four years because I have never done all my ngondro in less than three or four years. My father told me that you have to do that, you have to choose what you are going to study, not like in traditional Buddhism in which someone tells you what to do. When you are a Dzogchen practitioner, you have to choose what you want to do and what you do has to have a very strong link and connection with the teaching and the knowledge you have. So you take a course of study or a commitment to do something for some years that will seriously improve your knowledge, meaning the knowledge of Dzogchen. You take that kind of commitment and you have to complete it and have some kind of result.

When I started, I didn’t really have this idea, but a few months later, the first time I heard some very strange music made of sounds, of noises – really disturbing sounds as if they were made in the early 50s with equipment for testing waves for physics labs – I understood that there is something interesting to discover that can be a way to rethink totally and have some interesting insights. So I proceeded in this study and now I have published my first work.

Thank you very much for your time and this interview.

***

You can purchase the composition ATIMONLAM at Shang Shung Publications’ shop: https://www.shangshungpublications.com/en/explore/atiyoga-dzogchen-and-buddhism/product/atimonlam-english

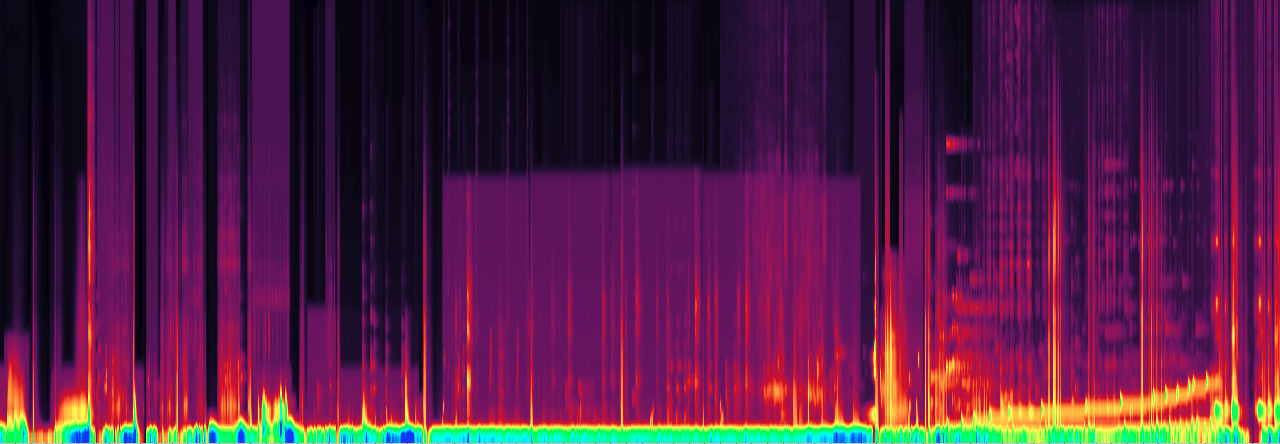

Featured image: ATIMONLAM spectrogram. Courtesy of Namkhai Yeshi.