What can be achieved even in difficult times

John Shane

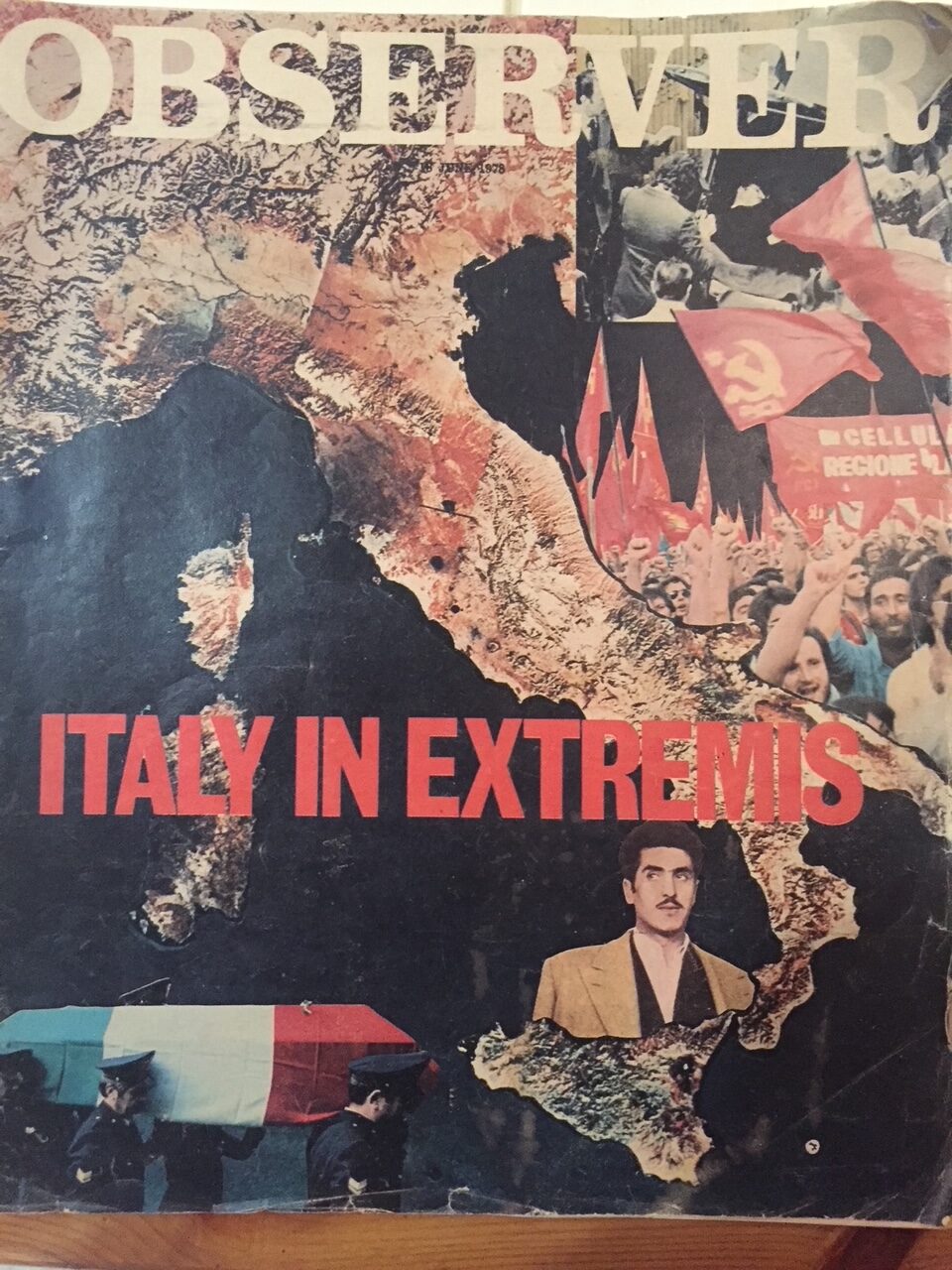

I still have the copy of the Magazine section of the Observer UK National newspaper that I bought at a London airport on Sunday 18th June, 1978 when I was on the way to attend a retreat with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu.

The magazine contained a long and lavishly illustrated article with the title ‘Italy In Extremis’ that detailed the political upheaval in the country to which I was traveling.

Those turbulent years of political upheaval in Italy became known as the ‘Anni di Piombo’, ‘The Years of Lead’.

The Years of Lead

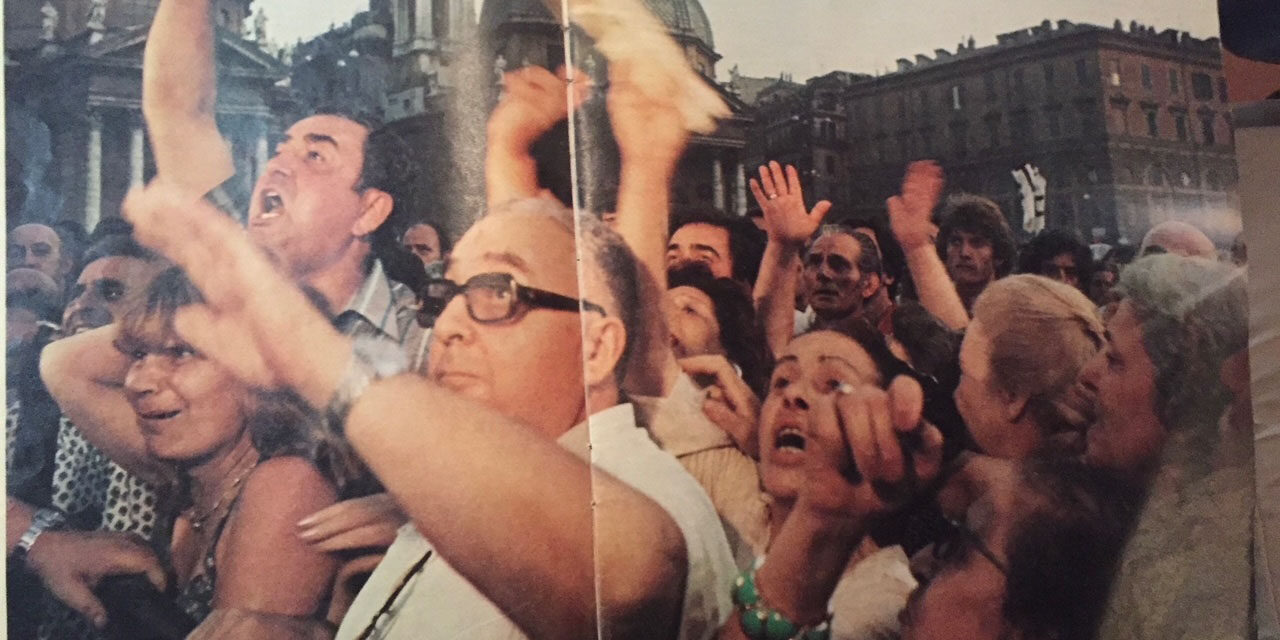

The Years of Lead was a period of social and political turmoil in Italy that lasted from 1968 to 1988, marked by a wave of both far-left and far-right political terrorism in the country that continued until mid-1988, by which time 428 people had been killed in the political violence

Far-left groups such as the communist Red Brigades and the anarchist Potere Operaio and far-right groups such as the National Vanguard and Ordine Nuovo (backed by the ultraright Propaganda Due secret society) engaged in street clashes against each other, and they also launched terrorist attacks such as bombings (targeting government buildings, each other’s rallies and homes, or public areas and assassinations (targeting judges, lawyers, policemen, or rival militants.)

In 2025, as all over the world we are living through difficult times, I remember that, despite everything that was going on – and very serious things were going on – in the difficult times of ‘The Years Of Lead’, we were able, with our teacher Chögyal Namkhai Norbu to found Merigar.

I was present in Italy in the earliest days of Merigar during the very difficult times of The Years Of Lead, and I have many hair-raising personal stories of dangerous incidents that I personally went through in the earliest days of Merigar as a young foreign person in Italy, who – although I was not and had never been in no way affiliated or associated with any political group of any kind – was considered ‘suspicious’ in the eyes of the authorities just because of my youthful appearance and my association with the Dzogchen Community, a group who were then seen as being ‘outside the norms of the day’ and were thus officially ‘suspect’.

I had intended to write an article for ‘The Mirror’ about what I and many of the ‘pioneers’ of Merigar went though at the time of the founding of Merigar during ‘The Years Of Lead’, but, unfortunately I am having some serious health problems and am not well enough to do so.

I will try to write that article in future and publish it either in ‘The Mirror’ or on my Substack, but, for now – as I reminder of what can be achieved as a spiritual community even in difficult times – I would like to share with you an article I wrote about the early days of Merigar that was published in ‘The Merigar Letter’ newsletter in 2011.

It was possible for us to refine the pure gold of study and practice even in the difficult times of ‘The Years Of Lead’ in Italy as we founded Merigar, and we can do the same in the difficult times we are facing today in so many parts of the world.

JS.

(If you have not already done so, please also take a look at the work I have published on Substack at https://johnshanewayofthepoet.substack.com and, if you enjoy it, it would mean a lot to me if you would please support my work by subscribing there to my newsletter. Thank you.)

Rainbow Over The Fire Mountain: The Early Days Of Merigar.

By John Shane

Article published in the Merigar Letter newsletter in 2011

In 1981, perhaps the least likely thing that the inhabitants of the town of Arcidosso imagined would happen is that Tibet would arrive on their doorstep.

And yet that was precisely what was about to happen.

In those days hardly anyone in rural Tuscany gave a thought to the far off and almost mythical ‘Land Of The Snows’, that had remained closed off behind the high Himalayas for so many centuries.

The people of Italy were, in any case, at the time, preoccupied with problems much closer to home.

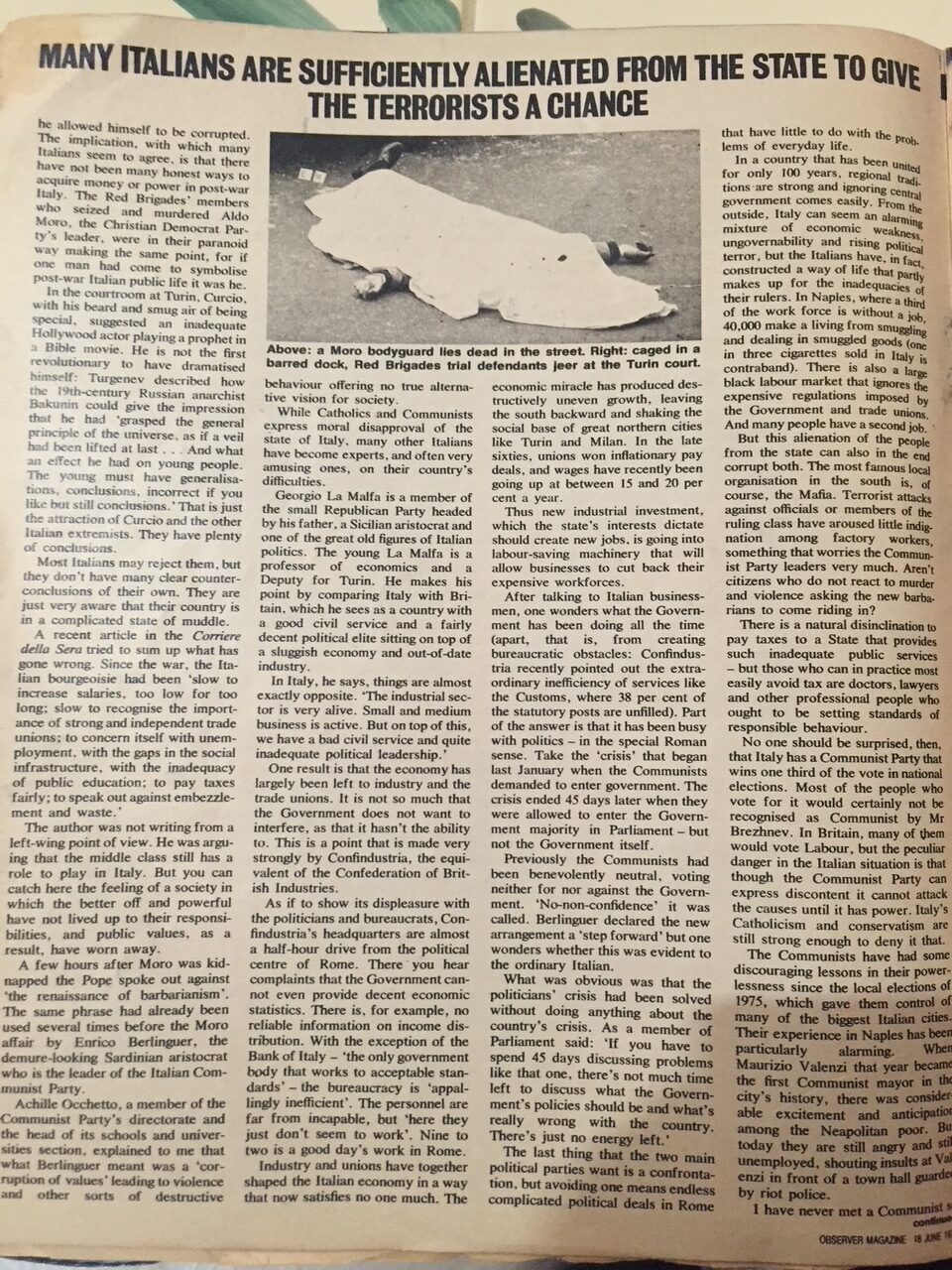

The day in 1981 on which I set out to fly from London to Pisa to look at the land that would become Merigar, a few weeks after the contract had been signed for its purchase, I bought ‘Time’ and ‘Newsweek’ in a kiosk on the way to the check-in desk at the airport, and saw that the cover articles of both magazines were about the latest activities of the Red Brigades who were terrorizing the country, with lurid photos of bombed-out buildings and bullet-ridden bodies in various Italian cities. Together with the ongoing problems caused by organized crime, Italy’s recurring economic troubles, the prevailing political turmoil was the main topic in the headlines.

In the midst of the continuing national crises of the day, Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, who was at the time the Professor of Tibetan and Mongolian language and culture at the Oriental Institute of the University of Naples, had been searching for a place to serve as a base for the growing community of individuals from all the world who had sought him out, hoping to receive spiritual teachings from him.

If Norbu – as he then permitted us to call him, using his first name – had been reluctant to assume the role of a spiritual teacher in the first place, preferring to remain a private person working to maintain his family life, he was even more reluctant to found the kind of center that he saw springing up around other Tibetan Lamas. ‘The real principle of the Teachings is to be found in the individual,’ he would say, ‘the individual is the true center’.

And yet such was the quality of his teaching and his growing reputation that people continued to seek him out, and as their numbers grew he found that the pressure on him and his family, as well as the needs of the students, required him to act.

Aware as he was of the tendency for formal religious institutions to develop in ways that can come to obscure and contradict their essential message, he was instinctively wary of forming any kind of organization.

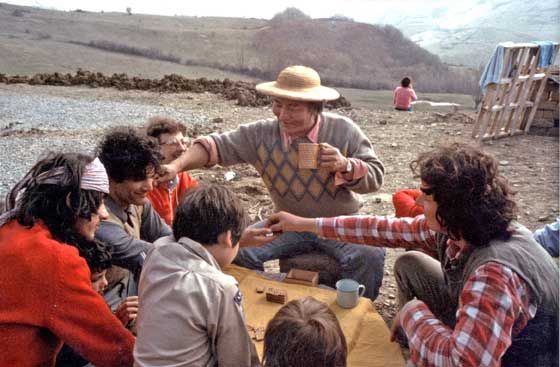

And so, for the first years that he was teaching, all the retreats at which he taught were held in a variety of improvised locations, such as out of season hotels, resorts that were taken over for a few weeks, and – on one occasion – in a large ruined farmhouse with no windows or doors in the mountains in northern Italy, where, appropriately enough, he taught us about death and dying. His students became used to following him from place to place like the nomads, setting everything up for the duration of the retreat, and then dismantling it all, before moving on to the next place.

Perhaps it was only when he felt that a few of his students understood that the essence of the spiritual teachings he was conveying should not be mistaken for the trappings of culture or for the structure of an organization that he felt he could take on the challenge of the purchase of a place of our own as a base for the teachings. But in any case, when, after much searching, a suitable place was finally found on Monte Amiata, just to remind his students not to forget why he had been reluctant to allow any centers to be created around his teaching, he called it a ‘Gar’, which in Tibetan means a nomad’s encampment – in this case ‘Merigar’, the encampment of the fire mountain, Monte Amiata being an extinct volcano.

Rinpoche has said recently, ‘I never had a plan as to how I would go ahead… I have always worked with circumstances as they arose’.

When we speak about the Dzogchen teachings, we are, after all, talking about a teaching that insists that one lives in the present moment, which is all we can ever know. The past is, of course, over and done, and will never return, and the future does not yet exist.

A Master, such as Chögyal Namkhai Norbu, always remains present, without distraction, and his undistracted presence has enabled him to respond with extraordinary precision to the challenges of developing his Community around the world, overcoming great difficulties with remarkable clarity, patience, and perseverance.

When I arrived at Pisa airport that day in 1981, I hired a car and drove up to Arcidosso for the first time. After looking around the town, I found a room at the Hotel Giardino, and persuaded the local real estate agent who had been involved in the purchase of the property for the Community to drive up the mountain with me to show me the house and land that we had just bought.

It was an overcast day, and low clouds hung over Monte Amiata. When we arrived at the end of a long dirt road, we came to a locked gate, and parked our cars. I climbed over the gate, and turning a corner, could see what looked like a ruined farmhouse in the distance.

At that moment, the sun came out, and a huge rainbow arose that went from one horizon to the next, and at the same time, a herd of small goats came running out of the building down the track towards me.

I took out my camera to capture an image of the moment, and I still have the photo.

But, of course, as well as being a symbol of auspicious circumstances, a rainbow is also a symbol of the illusory nature of all that manifests, and I have never forgotten that when I am at Merigar.

No matter how solid it appears, even Monte Amiata, even Merigar, are, from the ultimate point of view, only as real as an appearance in a dream.

Yet the dream arises, like a rainbow, illusory but apparent, the product of the play of impermanent causes and conditions, with no inherent self-nature.

And in the dream of our lives we act to accomplish our aims, even as we are aware that their nature is, from the absolute point of view, illusory.

I am always amazed at Rinpoche’s courage: with very little in the way of financial resources – much of which he provided himself from his own savings – and with only a group of young people who were more blessed with enthusiasm than with experience, he bought a ruined farmhouse on a remote mountainside in Toscana and proceeded to turn it into a major center for the preservation of the essence of the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan culture.

Together with a small number of others from various countries around the world, I moved to Toscana in 1981 to help with the founding of Merigar. If I ask myself now what on Earth the inhabitants of the local towns must have thought of us at the time, I know that it was confusing for them.

We were young, we had long hair, we wore strange clothes, a high proportion of us were foreigners who spoke very little or very bad Italian, and we had no visible means of support.

Yet the local people welcomed us into their homes, their restaurants, their shops and their offices with an open-heartedness that does credit to the great traditions of hospitality of the region, and I will always be deeply grateful to them for that.

Somehow or other, in the midst of the political confusions in Italy at the time, when the hard-working people of the Amiata region saw on the TV news every day reports of young people who were losing their heads in ideological dogma that led them to commit acts of violence against the state, there was still enough trust in the hearts of the local people to welcome us, no matter how strange we – and what we were doing up on Monte Amiata – must have seemed to them.

At first we all lived in the same house together with Rinpoche. There was no other place to sleep. In the main rooms of the first floor of what is now the Serkhang, or Golden House, Rinpoche had the only bed, and the rest of us slept on the floor, like caterpillars, in our sleeping bags. There was no electricity, no telephone, and no running water. We had no indoor toilets.

We had very little capital, so we had to try to do everything ourselves, rather than hiring professional builders. Everyone worked, and Rinpoche himself led from the front as always, working harder than everyone else.

I stood shoulder to shoulder with Rinpoche digging out the cowsheds that are now Merigar’s shop and kitchen. I wheeled barrows of cement to him as he built the retaining wall behind the house that keeps the hillside from sliding down.

In the early days, when we were getting the house in order, everyone worked and ate and slept in the same large open-plan upstairs room together, and everyone played together, too. There was endless laughter.

Rinpoche taught us many things in the formal sessions at the retreats that took place at intervals, but we learned so much from just living with him, from just being with him. We did a lot of practice, we worked hard, and we had so much fun.

Of course, there were many difficulties, but Rinpoche never seemed to get discouraged.

I have the abiding image of him sitting with a group of students around him in the garden playing a board game with one student at a time. Each student in turn would try to beat Rinpoche, but he would always win. No matter how much we tried, no one could beat him. After a while, this was not much fun for Rinpoche. So he began playing with one person, and as usual he won. But then he turned the board around, and, taking the hopeless losing position of his opponent, he began to fight back, until he had once again cleared the board of his opponent’s counters and had won again. Then he turned the board around, took the losing position again, and once more turned it into a winning position, repeating this over and over again, much to everyone’s astonishment and amusement.

The same was true when we encountered difficulties with planning applications, bank loans, or people who let us down in one way or another: once he had set out to do something, Rinpoche never gave up.

Some of that must have rubbed off on us. We, his students, learned from his example, and became stronger ourselves in our own lives. The Dzogchen Community developed, and, in time, more centers were founded all around the world. But Rinpoche has always referred to Merigar as ‘the navel’, in the sense, that it is from the navel, where the umbilical cord connects, that a baby develops in its mother’s womb.

Just as my experience of Merigar began with a rainbow appearing out of nowhere, so these words have appeared on my computer screen as the imprint of thoughts passing through my mind, and now they will travel as digital bits and bytes via wi fi and down cables from country to country to another computer from which they will be printed out and reassembled as words on paper which you will read to create images in your mind of the early days of Merigar.

It is my hope that this article will help those visiting Merigar for the first time to understand the conditions in which it came into being and will also help those of us who are responsible for Merigar to remember to continue to maintain it in the spirit in which, all those years ago, its founder intended.

John Shane©2011

John Shane is the Editor of ‘The Crystal And The Way Of Light: Sutra, Tantra, And Dzogchen’, a book of the Dzogchen Teachings of Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, published by Snowlion Publications.