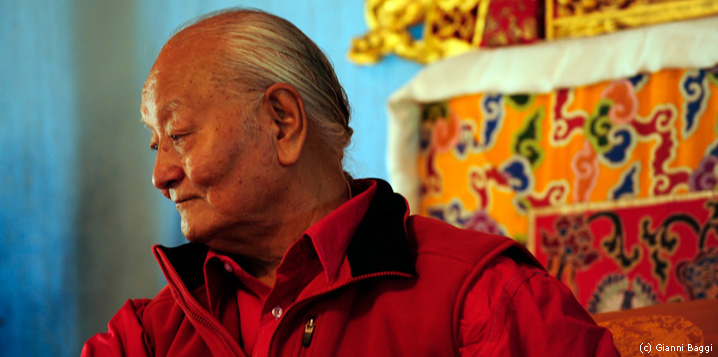

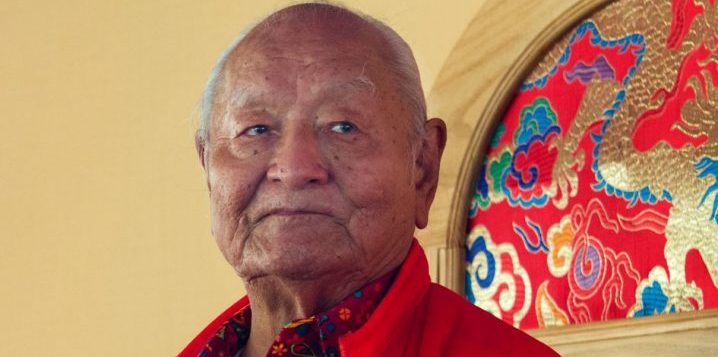

Chögyal Namkhai Norbu

Transcribed from the Song of the Vajra Retreat, Hong Kong 2012, May 18, day 3, part 1

Continued from the last issue of The Mirror, no.168.

First of all, in general we consider the Song of the Vajra to be in the language of Oddiyana, and not only the Song of the Vajra but all important mantras such as the 25 spaces of Samantabhadra. But we cannot affirm that they are exclusively in the language of Oddiyana because many teachings taught by Garab Dorje, which include tantras and lungs and upadeshas, originate from other dimensions. Many Dzogchen tantras have been preserved in their entirety, while some lungs represent only parts of those tantras. Many other tantras and also the source of all these lungs still exist in other dimensions. For instance, in the Dzogchen Upadesha teaching, particularly in the Dra Thalgyur tantra, there is an explanation of thirteen different Nirmanakaya dimensions in which important Dzogchen tantras and teachings exist.

When enlightened beings, that are beyond time and space, introduce methods and teachings in our dimension, they do not always use the same words. For instance, when we learn the Song of the Vajra we can find all the Thödrol tantras that explain six different kinds of liberation. We find these kinds of tantras in most Shitro practices, although they may have slightly different versions. Some intellectual people may ask which version is correct and which is not. If we are completely sure that these tantras are only in the Oddiyana language then we can ask that question, however, many teachings have been introduced from different dimensions so we cannot. What is most important is how we have received those mantras from our teacher and their pronunciation. If we apply them in that way, we can have realization so we should not go after things in just an intellectual way.

If we follow different teachers, we might receive the hundred-syllable mantra from all of them, but each one might pronounce it in a different way. Most lamas and teachers don’t say “vajra” but “benza”, “benza sato samaya manou palaya”, they chant it that way. Others don’t say benza but “bazra” which is a little closer to the Sanskrit pronunciation. However, my teacher, Negyab Rinpoche (gnas rgyab rin po che), from whom I received Dzogchen Semde, Longde and Upadesha, and his teacher, Katog Situ Rinpoche, closely followed the lineage of the Sanskrit pronunciation and always said “vajra” not “benza”. Also, my teacher at college who taught me Sanskrit always pronounced “vajra” when he read any kind of mantra which is why I am using it that way. But you shouldn’t worry if you learned “benza” or “bazra”. There is no problem and you can use it. I did not invent the way I use “vajra”; it is the way I received it from my teacher.

There is a story in the Sakyapa tradition about Sakya Pandita, a very important teacher. He was in Sakya monastery and one day, when he was walking along a river near the monastery, he heard the sound of Vajrakilaya coming from the river and thought that there must be a good practitioner of Vajrakilaya in the valley where the water came from.

Once he spent the whole day following the valley searching for the person who was doing the practice of Vajrakilaya. Finally he came to a rock and in the rock there was a cave and a yogi doing a personal retreat. When he asked this yogi what practice he was doing he replied “Vajrakilaya”, but he did not pronounce it “Kilaya” but “Chilaya”. Then Sakya Pandita thought it a little strange that he was not pronouncing it well because Sakya Pandita had a very high level of Sanskrit and was also one of the translators. Then he asked the yogi how he chanted the mantra of Vajrakilaya and the yogi replied, “I chant OM VAJRA CHILICHILAYA SVAHA”. Sakya Pandita told him that he was not pronouncing it well, that in Sanskrit it is pronounced KILIKILAYA and he should pronounce it that way.

The yogi said he wanted to check, took his phurba, put it on a rock and said, “OM VAJRA KILIKILAYA SVAHA”, but the phurba did not penetrate the rock. Then he said, “OM VAJRA CHILICHILAYA SVAHA” and when he struck the rock with the phurba, it entered. Then Sakya Pandita was very surprised and understood that one should not go only after pronunciation and that this was a fully realized yogi of Vajrakilaya.

Later he invited this yogi to Sakya monastery where he gave the Vajrakilaya initiation. In the Sakyapa tradition when we do Vajrakilaya practice there is also a specific lineage of this mahasiddha. When we receive the initiation and do this practice we should chant OM VAJRA CHILICHILAYA SVAHA HUM PHAT. That is a very good example that shows how important the way we receive transmission is and how we should do the practice that way with confidence in order to have realization.

In ancient times many translators, such as Vairocana, studied and translated most Dzogchen tantras and books from the language of Oddiyana, not Sanskrit. Although there are many words that are very similar in Sanskrit and the language of Oddiyana, the way of using them in teachings and their grammatical systems are not the same. For example, in Sanskrit the adjective is always placed before the noun: Dzogchen is Mahasanti. In the Oddiyana language, the adjective comes after the noun, just like the Tibetan language, Santimaha. The way of using the adjective is very similar to Tibetan but the language is different. When we say Santimaha, maha is the adjective and it comes after not before. Most of the Dzogchen tantras are in the language of Oddiyana and we can understand that because the adjective always comes after the noun. This is the difference between the Oddiyana language and Sanskrit.

Longchenpa translated the meaning of the Song of the Vajra, from this Oddiyana language. This version is what is called the non-dual or union of the state of Samantabhadra, yab and yum. In the Dzogchen tantras and also in many Thödrol tantras two kinds of Song of the Vajra are presented: the first is called the state of the yab, Samantabhadra, while the second is the state of Samantabhadra yum, Samantabhadri. There are always two kinds, however, there is only one union of the yab and yum, which is the one we are using when we sing. Longchenpa roughly translated its sense.

The real meaning of the Song of the Vajra is the essence of the Dzogchen teaching. But even though it is the essence there is an explanation of which I will give a rough translation.

These are the first four verses.

མ་སྐྱེས་པས་ནི་མི་འགག་ཅིང༌།

།འགྲོ་དང་འོང་མེད་ཀུན་ཏུ་ཁྱབ།

།བདེ་ཆེན་ཆོས་མཆོག་མི་གཡོ་བ།

།མཁའ་མཉམ་རྣམ་གྲོལ་དགོས་པ་མེད།

ma skyes pas ni mi ‘gag cing

‘gro dang ‘ong med kun tu khyab

bde chen chos mchog mi g.yo ba

mkha’ mnyam rnam grol dgos pa med

EMAKIRIKIRI

MASUTAVALIVALI

SAMITASURUSURU

KUTALIMASUMASU

མ་སྐྱེས་པས་ནི་མི་འགག་ཅིང༌།

ma skyes pas ni mi ‘gag cing

This means unborn. There is no beginning or birth and no interruption or end.

།འགྲོ་དང་འོང་མེད་ཀུན་ཏུ་ཁྱབ།

‘gro dang ‘ong med kun tu khyab

There is no going and no coming because it is pervading

།བདེ་ཆེན་ཆོས་མཆོག་མི་གཡོ་བ།

bde chen chos mchog mi g.yo ba

Dechen means total bliss, the supreme real condition of the state. In miyowa, the word yowa means movement. When we are integrated with movement there is no consideration of movement.

།མཁའ་མཉམ་རྣམ་གྲོལ་དགོས་པ་མེད།

mkha’ mnyam rnam grol dgos pa med

Everything is self-liberated, beyond time. There are no defects or problems.

This first group is connected with the Dzogchen Semde series of teaching. Later on I’ll explain about the Dzogchen Longde and Upadesha series.

Then there is the second group.

།རྩ་བ་མེད་ཅིང་རྟེན་མེད་ལ།

།གནས་མེད་ལེན་མེད་ཆོས་ཆེན་པོ།

།ཡེ་གྲོལ་ལྷུན་མཉམ་ཡངས་པ་ཆེ།

།བཅིང་མེད་རྣམ་པར་བཀྲོལ་མེད་པ།

rtsa ba med cing rten med la

gnas med len med chos chen po

ye grol lhun mnyam yangs pa che

bcing med rnam par bkrol med pa

EKARASULIBHATAYE

CIKIRABHULIBHATHAYE

SAMUNTACARYASUGHAYE

BHETASANABHYAKULAYE

These four verses are connected to the Dzogchen Longde series of teaching.

།རྩ་བ་མེད་ཅིང་རྟེན་མེད་ལ།

rtsa ba med cing rten med la

This means that when we search for the root, the origin, we cannot find anything that confirms it. Also there is nothing that is connected with this origin. Even if there is nothing confirming from where it develops, there are no secondary things related with that.

།གནས་མེད་ལེན་མེད་ཆོས་ཆེན་པོ།

gnas med len med chos chen po

When we consider ourselves to be in the state of contemplation this is just our mental concept. If we are really in the state of contemplation, we are beyond even this concept. It is the same when we consider the dimension of the Sambhogakaya. When we ask ourselves what the Sambhogakaya is we say it is a pure dimension, a manifestation of the Dharmakaya. How does it manifest? In different kinds of forms such as wrathful, peaceful and joyful manifestations. All these things are our mental concepts, which are indispensable to enter this state, but they do not really represent the Sambhogakaya. The Sambhogakaya means that when we are in our real nature and discover our infinite potentiality, in that moment we are totally beyond time and space. This is the real condition of the Sambhogakaya.

Nadmed lenmed chö chenpo: there is nothing we can create or take, it is always total existence, the real condition.

།ཡེ་གྲོལ་ལྷུན་མཉམ་ཡངས་པ་ཆེ།

ye grol lhun mnyam yangs pa che

Ye means how our real condition is from the beginning, the self-liberated state. In general the Tibetan word ye is also in the word for “wisdom,” yeshe, and in “since the beginning,” yene.

།བཅིང་མེད་རྣམ་པར་བཀྲོལ་མེད་པ།

bcing med rnam par bkrol med pa

There is not some ordinary dualistic vision we can be conditioned by, nor is there something we can liberate. Everything is the relative condition in our mental concepts. These verses are very much related to the principles of the Dzogchen Longde.

Edited by L.Granger

Final editing Susan Schwarz

Tibetan & Wylie by Prof. Fabian Sanders

To be continued in the next issue of The Mirror